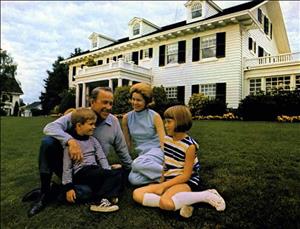

The Butler-Jackson House at 1703 Grand Avenue is significant for its place in Everett's architectural history and as the home of two prominent and influential, and very different, Everett residents. The large Colonial Revival house on a bluff overlooking the port was designed by August F. Heide (1862-1943?), an important local architect whose buildings helped shape Everett's downtown and residential neighborhoods during its boom years. The house was built in 1910 for William C. Butler (1866-1944), the conservative Republican banker and businessman who financed much of the city's early development and controlled it economically and politically for decades, his wife Eleanor Hughes Butler, and their son. In 1967, Democratic United States Senator Henry M. "Scoop" Jackson (1912-1983), his wife Helen Hardin Jackson (1933-2018), and their two young children moved into the home. Henry Jackson savored the irony of owning the big house built by the tight-fisted Republican banker, where he had delivered newspapers as a boy. The Butler-Jackson house, added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1998, remained the home of Helen Jackson until her death.

Easterners in Everett

William and Eleanor Butler arrived in Everett in 1892 while the city was in the midst of its explosive rise from tiny pioneer settlement to major industrial and commercial center. Everett's growth, rapid even by the standards of Washington boomtowns, was initially financed and promoted in large part by Eastern financial interests, most notably John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937). William Curtis Butler and Eleanor Hughes, natives of Paterson, New Jersey, who married in 1890, were themselves representatives of prominent Eastern families. Butler's father was a wealthy manufacturer and his brother Nicholas Murray Butler (1862-1947) became president of Columbia University in New York City, a leading figure in the national Republican party, and winner of the 1931 Nobel Peace Prize.

William Butler was a mining engineer with an 1887 degree from Columbia's school of mines. His mining expertise, but more importantly his connections to John D. Rockefeller, brought the Butlers to Everett. Rockefeller first invested in the nascent city in 1890, when Tacoma lumberman and speculator Henry Hewitt Jr. (1840-1918) brought Rockefeller representative Charles L. Colby (1839-1896) together with local landowners to establish the Everett Land Company and promote an industrial city on the thickly forested peninsula located between the Snohomish River estuary and Port Gardner Bay. Within a year, the Eastern financiers acquired substantial interests in the gold and silver mines at Monte Cristo, deep in the Cascade Mountains east of Everett. Rockefeller dispatched Butler to oversee construction and operation of a concentrator in Monte Cristo to process the ore from the mines and a smelter in Everett where the Puget Sound Reduction Company would produce bullion from the concentrates.

Bust and Boom

Everett's first boom did not last long. The Panic of 1893 caused the ore smelter, along with most of the new industrial development in Everett, to close at least temporarily. Many eastern investors pulled out. By 1899, Rockefeller's Everett Land Company had sold out to the Everett Improvement Company controlled by James J. Hill (1838-1916), head of the Great Northern Railway. However, Butler stayed and invested in banks, beginning with the Everett National Bank founded by Henry Hewitt. By 1901, with Butler as president, his bank acquired the slightly older First National Bank, and he remained president of First National until 1941, while also obtaining controlling interests in several other financial institutions.

Butler helped finance the sale of the Everett Land Company and the new boom that began as good times resumed around 1900. One source notes, "[t]he town's revival was built on borrowed money -- most of it from Butler" (National Register, 10). After Frederick Weyerhaeuser built a large timber mill, Butler directed his investments to mills and other timber industry development, further enriching himself and helping set Everett's future as a mill town. Along with his control of Everett banks and mills, Butler owned timber lands throughout the Northwest and was a major figure in the early years of large-scale logging in the region. He also continued to manage the Puget Sound Reduction Company, which rebounded to employ several hundred workers and to process ore from as far afield as Alaska and Mexico before closing in 1912.

As the economy prospered, many Everett business owners erected impressive new homes. While others built closer to town, the Butlers chose a large lot that in 1910 was at the northern end of the city's development, with woods beyond. Set on a bluff, the house faces out over the bay with sweeping views across the water to the Olympic Mountains. Butler was perhaps more interested in watching the mills on the waterfront below the bluff, given his investment and ownership interest in many. Indeed, during the Butlers' era smoke from the numerous mill smokestacks often obscured the now highly prized water and mountain views.

August Heide

The Butlers turned to August Heide, one of the leading architects in Everett at the time. Born and educated in Illinois, Heide moved to Tacoma in 1889, where he began working with Henry Hewitt, soon to become the "father of Everett." Heide and his partner Charles Hove became the architects for the Everett Land Company, which was responsible for most development in Everett through 1899. Heide designed a number of the early buildings that now anchor Everett's historic downtown, including four that are on the National Register of Historic Places: the Swalwell Building (1892) and Diefenbacher Building (1903) (both part of the Swalwell Block); the Carnegie Library (1904); and the Snohomish County Courthouse (1910 - Heide earlier designed the 1897 courthouse, which burned in 1909). Heide also designed many Everett residences, including his own "modest but beautifully designed 1895 cottage at 2107 Rucker" (National Register, 7).

For the Butler family, Heide designed an imposing and dignified "two and one half story Colonial Revival town home with Federal style features" (National Register, 3). In front, a large central pillared entry porch is flanked by symmetrical sets of windows on the first two floors, with three gabled dormer windows above. Inside, a large foyer opens to an elegant stairway. A spacious living room, formal dining room, and library occupy the front of the first floor. The rear was given over to servant work areas, including kitchen (that portion of the home has since been remodeled). The family bedrooms and a billiard room take up the second floor. The third floor (also since remodeled) housed maids' rooms and a workroom.

The National Register nomination form notes several respects in which the house reflected its owners' heritage and personality. The original solarium and sleeping porch on the south side (now fully enclosed as a sunroom) "are certainly products of an Eastern owner remembering warmer nights and summers than are common in the Pacific Northwest" (National Register, 7). And the classic Colonial Federal style was a common choice for wealthy homeowners of the day to convey prestige and refinement. Like Butler himself, his house, "surrounded by property and overlooking his industries," was "reserved and aloof" (National Register, 7).

Power Behind the Scene

Despite Butler's power and influence, he and his wife deliberately maintained their distance from Everett society. Although they appeared at important social functions, they rarely entertained and few visited their home. Both Butlers, especially Eleanor, withdrew even further after their only child, 16-year-old William Jr., died in 1912 following an operation for appendicitis.

Butler always shunned publicity. "The local newspaper understood that it was never to print anything about him" (Prochnau and Larsen, 88). He deliberately avoided creating a paper trail, signing very few documents. Nevertheless, he influenced the destiny not only of the city as a whole but also that of many individual residents. By granting or denying bank loans and mill jobs, Butler determined whose business succeeded, who could own a home, even who could work in town. The manner in which he exercised this power did not make Butler popular. Indeed, he became known as "the meanest son-of-a-bitch in town" (Prochnau and Larsen, 98). Everett oral history is replete with stories of Butler scrutinizing the opening hours of businesses and the grocery bills of homeowners who received loans from him, of foreclosing out of spite, and of refusing to pay small bills he owed.

Throughout his life, Butler used his financial power and his behind-the-scenes leadership of the Republican party to oppose economic or political reform. During the 1916 shingle mill strike that culminated in the Everett Massacre, Butler pushed fellow mill owners to take a hard line against the workers, hiring strikebreakers and armed enforcers to keep the mills open rather than acceding to the demand that Everett mills pay the same wages as others around Puget Sound. Twenty-four years later, Butler was still fighting increased wages that he saw as a threat to private enterprise. When Henry Jackson, who years later would own the Butler home, was first elected to Congress in 1940, Butler complained to him that the high wages paid by the federal government to workers expanding Everett's Paine Field airport were causing wage inflation and hurting business. Jackson, a New Deal Democrat and staunch economic liberal throughout his career, responded that higher wages, giving workers more money to spend, might benefit banks and other businesses in the long run.

Changing Hands

Butler died in his Grand Avenue home on January 6, 1944. In keeping with his life, the funeral service at the home two days later was "attended only by members of the family, business associates and close friends" ("Last Rites"). Some time after Butler's death, local Cadillac dealer Charles Allen and his wife bought the house. Later, banker William Carpenter and his wife owned it. In 1967, Henry and Helen Jackson bought the former Butler home. Although the Jacksons lived comfortably, they never approached the Butlers' relative financial status, but Henry Jackson's senatorial salary and his noted frugality made it possible to purchase the dignified old home for what was even then the bargain price of $65,000.

Growing up in Everett as the son of working-class Norwegian immigrants -- his father Peter changed the family name from Gresseth to Jackson -- Henry Jackson was aware of William Butler, his power, and his grand home long before their 1940 meeting. Demonstrating industriousness (if not the class background) that the older man might have admired, the young Henry not only delivered the Everett Herald, but after completing his route sold the paper on downtown street corners. Butler's chauffeur sometimes bought the banker's paper from Henry, who years later also recalled delivering newspapers to the Grand Avenue house where Butler lived.

Jackson went on to become one of the most successful and significant political figures in the history of the state. He won his first elective office, Snohomish County Prosecutor, in 1938, three years after graduating from law school, and went on to win six elections to the United States House of Representatives followed by six to the Senate (beginning in 1952), often by record margins. Jackson was an outspoken advocate of increased military spending and a hard line against the Soviet Union, an equally consistent supporter of social welfare programs, civil rights, and the labor movement, and the sponsor of landmark environmental legislation.

In the Banker's House

Jackson was only 28 when he first entered Congress in 1940 (becoming at the time its youngest member), and for the next quarter century, while in Everett, he continued to live in the home at 3602 Oakes Street where he grew up. He spent most of the year, during which Congress was in session, in Washington, D.C. Jackson remained single until 1961, when he married Helen Hardin, who worked in the office of his Senate colleague Clinton Anderson of New Mexico. Even after the marriage and the birth of their children Anna Marie in 1963 and Peter in 1966, the Jacksons continued to stay while in Everett with Jackson's sisters in the Oakes Street house until they bought the former Butler home in 1967.

No doubt the Jacksons would have enjoyed the large, elegant house and its impressive views regardless of its history. But Henry Jackson certainly got extra pleasure in knowing that his family now occupied the home built by the Republican banker who dominated the town of his boyhood and looked down on workers and immigrants. While showing people around the house, the senator liked to say:

"Wouldn't old Mister Butler turn over in his grave if he knew that a Democrat — the blockheaded son of Peter Gresseth, an immigrant Norwegian laborer — owned his big house?"(Prochnau and Larsen, 100).

Jackson emphasized the point by prominently displaying portraits of his immigrant parents in the home.

Unlike the Butlers, the Jacksons frequently opened the Grand Avenue home to the public. Jackson enjoyed public contact almost as much as Butler shunned it -- his gift for making one-on-one connections was one of the talents that made him a masterful campaigner. In addition to political gatherings that were part of Henry Jackson's work, the Jacksons hosted numerous cultural and charitable functions, a tradition that Helen Jackson continued for years following her husband's death. The family returned to the house when Congress was not in session and always at Christmas. Over the holiday, the Jackson home was open to neighborhood carolers and the senator sometimes joined his neighbors in caroling.

Changes in View

As one of the more powerful figures in the history of the United States Senate, Jackson influenced the history of Everett -- along with that of the state, nation, and world -- at least as much as Butler did, although of course in very different ways. The National Register form points out that their differing influences are dramatically demonstrated by changes in the view from the house since Butler built it. In Butler's day, the mills he financed dominated the waterfront below the bluff and smoke from their chimneys often blocked the view. The view is clear now, in part due to protective environmental laws like the 1969 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) that Jackson sponsored, although the closure of the mills is a more direct cause. Much of the waterfront land below the Butler-Jackson house formerly occupied by mills is now home to Naval Station Everett, a modern navy base that, although constructed since Jackson's death, is in part a legacy of his success at both boosting military spending and directing federal money to his home state and town.

Henry Jackson's life, like Butler's, ended in the Grand Avenue home, where he suffered a fatal heart attack on September 1, 1983. Efforts to revive him failed and he died several hours later at Everett's Providence Hospital. Given his public persona and great popularity -- even constituents who had never met him personally felt they knew him -- Jackson's funeral drew large crowds, ranging from leading politicians and local residents, to the Everett church where the service was held and to several additional halls where the proceedings were televised. Helen Jackson continued to live in the home for another 35 years until her death there, with her family around her, on February 24, 2018.

Historic Landmark

When the Butler-Jackson House was named to the National Register of Historic Places in 1998, the nomination paperwork noted that the exterior seemed nearly unchanged since the Butlers lived there. From the front, the only slight changes to be seen were the full enclosure of the sunroom on the south side and the use of a composition roof in place of the original wooden shingles from Everett mills. In back, Helen Jackson had renovated and enlarged the two-story former service wing in 1984. Although the interior had been modernized, "the basic floor plan ... and the sense of timeless quality and classic integrity has been retained" (National Register, 3).

Thus the Butler-Jackson House preserves the essence of August Heide's design, illustrating an aspect of life during Everett's early boom years. At the same time it stands as a witness to the century of changes since that time and to the major roles played in Everett and Washington history by the two influential residents who called the house home and whose names it now bears.