Frances Payne Larrabee was a prominent and influential Bellingham clubwoman. She was instrumental in the founding of the Bellingham Bay Home for Children, a safe haven for homeless children. She became an ardent leader in numerous women's clubs, and perhaps most important, was the main benefactor and driving force in establishing a viable YWCA in Bellingham. She was also a dynamic decision maker and leader for the St. James Presbyterian Church in Fairhaven. She joined Bellingham's first literary club, the Monday Club, and soon after, the focus changed from providing its members with stimulating and intellectual challenges to analyzing some of the most pressing social and political issues of the Progressive era. Larrabee came from a privileged family of long American lineage, excelled in music, and was married to C. X. Larrabee (1843-1914), a multifaceted business tycoon. She was a willing leader in any organization in which she was involved, and had a robust affinity for aiding the less fortunate.

Early Years

Her family tree is traced to Sir John Payne (1600-1690). John Payne arrived in America in 1620 and settled in Virginia. Frances Payne was born in Missouri to Benjamin and Adelia Payne on January 15, 1867. She studied music at the Mary Institute in St. Louis and at the New England Conservatory of Music. She then studied in Berlin for a year under Oscar Reif.

Frances Payne and C. X. Larrabee met in Boston sometime in 1890, when he was in that city on a business trip and she was visiting friends with her mother. C. X. Larrabee and Frances Payne married in August 1892.

C. X. and Frances Larrabee

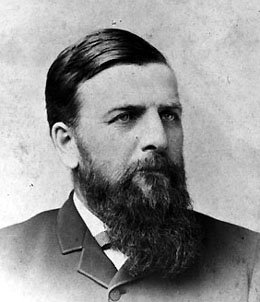

C. X. Larrabee held vast mining assets in both Washington and Montana. His other businesses included banking interests in Montana and Washington, as well as land development interests in Portland, Oregon, and in Washington's Whatcom County. In addition, he owned the Fairhaven and Southern Railroad, and the historic Fairhaven hotel in Fairhaven (later Bellingham). He was also a breeder of famous Morgan horses on a ranch in Montana. At one time, C. X. Larrabee held -- among other assets -- a 50 percent interest in the great Anaconda mine of Butte, Montana. And in 1910, C. X. Larrabee was listed as one of 54 notable people who lived during the early development of Northwestern Washington.

In addition, the 1926 publication of the History of Whatcom County provides biographical sketches of some one thousand notable people in early Whatcom County. Of those listed, only 36 are women. Frances Larrabee is not one of them. However, C. X. Larrabee is the 28th person listed in the text. He is chronicled as having “marched in the front ranks of those hardy pioneers who blazed the trails and made possible the development of the Pacific Northwest” (Roth). On the other hand, in that same biographical sketch, Frances Larrabee is given mention in only four lines of the last paragraph.

Volume I of The History of Whatcom County does provide insight into Frances Larrabee’s dedication to social issues as well as her philanthropic tendencies. Larrabee is mentioned as an officer, founder and/or board member in the summations of five Bellingham women’s clubs. But, only in the club history of the Young Women’s Christian Association does Roth expand on the extent of Larrabee’s civic accomplishments.

In Historical Shadows

It is apparent that Larrabee shared the fate of numerous clubwomen who received little historical recognition, despite the significant roles that they played in advancing feminism and social reforms during both the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Women’s clubs had been "ignored [and] dismissed as trivial or frivolous" by historians until the latter part of the twentieth century (Blair). This gender-biased practice -- along with the scale of C. X. Larrabee’s accomplishments -- placed Frances Larrabee in the historical shadows of her famous husband, while her considerable accomplishments were little more than footnoted.

Consequently, although individual scraps of historical information exist concerning her life and achievements, there is until now no single biographical essay that encompasses the scope of Larrabee’s personality and talents.

A Gifted Leader

Primary sources show that Larrabee possessed gifted leadership abilities, and that she used the venues provided by women’s clubs to assert those abilities. Political rhetoric was not her forte, and she was unencumbered by the limitations of political ideologies. However, she was a compelling example of someone committed to progressive social changes and gender equality. Larrabee exercised her political views by the ways she helped to build her community and by how she conducted her personal life.

Larrabee understood the power of her family’s wealth and unapologetically used that strength for the betterment of her community. In truth, Larrabee etched her own image into Whatcom County history and carved out her own place in the region’s social order. And, she by no means labored in the shadows of her pioneering husband despite the fact that he was a dominant figure in that small vanguard of individuals who oversaw the development of the foundational infrastructure of society in the Pacific Northwest.

Caring for Children

Frances Larrabee made an impressive impact on her new community when she and her husband arrived in Fairhaven, Whatcom County, in August, 1892. Larrabee immediately recognized a need in the community and acted decisively in helping those who were far less fortunate than she was. Within two months, she was instrumental in the founding of the Bellingham Bay Home for Children, a safe haven for homeless children in the northwestern region of Washington state. The home was incorporated on October 1, 1892. Larrabee served as founding director and by the end of the year, the Larrabees had contributed “a large unoccupied residence and a liberal sum of money" to the cause (Roth). By the end of January 1893, the residence was home to nine previously wandering children.

Larrabee made a longterm commitment to provide care for the children of other people -- who could not or would not care for their offspring -- at the same time that she was building her own family. Frances and C. X. Larrabee had four children; Charles Francis (1895) Edward (Ned) Conyers Payne (1897), Mary Adele (1902), and Benjamin Howard (1906). Along with caring for her own growing family, Larrabee continued to serve on the board of the children's shelter, holding the position of treasurer until 1899. In 1899, the responsibility for the homeless children’s care came under the auspices of the National Children’s Home Association, which established a branch facility in Seattle.

Church Leader

But Larrabee was just getting started with her civic involvement. Dorothy Koert, historian for the St. James Presbyterian Church in Fairhaven, hails Larrabee’s arrival as “an event which was to be of importance to the future of the church.” She goes on by stating that Larrabee “was energetic ... and until her death many years later, she was a moving force in the church” (Koert). Larrabee was ever present as a decision maker and leader of the church. For example, in April 1917, she was listed as the treasurer of the church, and she suggested that a new church building be constructed. Then, Larrabee donated four lots for the building site, and the contract was signed to construct the new building at a cost of some $5,000.

Larrabee seemed at her best during a time of crisis. During the peak of America’s involvement in World War I, several Bellingham pastors were called to serve as ministers for military personnel in Europe. On May 26, 1918, church members from St. James Church and the Methodist Church met to discuss the possibility of bringing the two congregations together on a temporary basis. Using a direct approach, Larrabee opened the meeting by stating without preamble: “This meeting has been called looking toward a temporary union of the Methodist and Presbyterian Churches of South Bellingham, Washington” (Koert). Then, Larrabee proceeded -- with four other members of a special committee -- to draw up details of a nine point agreement codifying the temporary alliance of the churches.

Although Larrabee’s church participation was not directly connected to her membership activities as a clubwoman, her work for the church provides an excellent opportunity to display her propensity for being involved in community building at many diverse levels.

The Monday Club

The longterm commitments Larrabee made to numerous women’s clubs fortunate enough to have her as a member made further use of the leadership attributes that she displayed in her work with her church. The Monday Club was the oldest literary club in the area and was organized in Fairhaven in the 1890s. Larrabee first appeared as a visitor to the club on April 6, 1906, and then as a member two months later at the end of the club’s season. She was an active participant in the club and on November 18, 1907, she presented a paper on child labor during a series of discussions concerning the era’s social problems. Although the club’s stated purpose was to present stimulating and intellectual challenges for its members, soon after Larrabee became a member there was a shift to social issues. By no means is this meant to give full credit to Larrabee for the shift in the club’s focus. However, her ongoing involvement in civic causes -- such as the Bellingham Bay Home for Children previously described -- and the leadership role that she so quickly asserted in the Monday Club -- infer that she was more than nominally involved in the club’s new found interests.

In January 1908, the subject of one club meeting was the question of alcohol consumption, a social problem of much interest to the Larrabee family. In a February 1908 meeting, at the Larrabee home, the discussion revolved around the value of music -- a lifelong passion in Larrabee’s life -- in child training. Then on February 17, 1908, Larrabee and her fellow club members discussed woman suffrage and co-education. And, on May 18, 1908, the club discussed racial issues. Thus was the Monday Club analyzing some of the key social and political issues of the Progressive era.

The minutes of the May 4, 1908, meeting reveal Larrabee's leadership: She introduced the complete program for the coming season. During the last meeting of the season, Larrabee advised club members of a Seattle woman’s open invitation to visit her home for all members attending the annual meeting of the Washington State Federation of Women’s Clubs. Larrabee went on to serve as vice president of the Monday Club from 1911 through 1916. In 1917 she was elected president of the club and served in that capacity through 1919.

Larrabee attended both the twelfth and thirteenth annual conventions of the Washington State Federation of Women’s Clubs as a representative not of the Monday Club but of the Chamenade Choral Club. Federation annual reports show that the choral club was established in October 1909, and it listed Larrabee as its president. In the 13th Federation Annual Report, Larrabee was listed as being a member of the federation music committee.

Larrabee and the YWCA

But Larrabee’s most significant club-related accomplishment was the leadership role she played in establishing a YWCA in her community. At the turn of the twentieth century, railroad stations and waterfront docks represented places where destitute young women were vulnerable and easy prey. These young women needed the security and assistance offered by an organization such as the YWCA. In 1906, the sudden arrival of victims fleeing from the 1906 San Francisco earthquake exacerbated the problem.

Larrabee may have felt a particular affinity for the young destitute women, because around 1890 (before her marriage) her immediate family lost most of its money and for a while “she had to support herself by coaching advanced piano students & playing the organ in the largest Methodist Church in St. Louis. She had no money of her own [other than what she earned] when she married ...“ (Bourque).

Discussions concerning the organization of a YWCA in Bellingham began in the fall of 1906. In December 1907, Larrabee was one of 15 charter members of the board of directors when the certificate of incorporation of the YWCA was filed. In March 1908, Larrabee was elected vice president of the board of directors and appointed as one of five Property Trustees. By 1910, Larrabee was president of the board of directors. During Larrabee’s presidential tenure of 1911, the association was struggling with lack of space and a lack of funds.

Although the dilemma still existed in the summer of 1914, the institution’s money problems were soon rectified. In Bellingham YWCA: Our Heritage, Randy Roebuck relates a story told to him by Arta Lawrence, who was in attendance at a YWCA board meeting held on July 21, 1914. Larrabee requested recognition by the chairperson and when acknowledged, Larrabee stated -- as she placed architectural plans for a new building on a table -- “speaking of the building, I have here something I’d like to present. Now if these plans meet with the approval of the membership, the Larrabees would like to build it for you” (Roebuck). The plans had been prepared by the renowned architect Carl Gould (1873-1939), which infers that Larrabee wanted to apply a lasting solution to a festering problem that had caused considerable angst among the founding members of the organization since its establishment.

Because she was not reticent to use a substantial part of her family’s assets to solve the club’s lingering financial problems, Larrabee succeeded in revitalizing a struggling YWCA that she had helped to found in 1907. Larrabee’s guarantee of a successful YWCA program in Bellingham provided a safe haven for the most vulnerable of women who might find themselves in need of temporary assistance. In addition, Larrabee’s philanthropy energized the community. When it was time to furnish the new building, nine clubs, 13 individuals, two businesses, and one church participated in funding that part of the project.

Larrabee the Businesswoman

Larrabee’s life had a much fuller meaning than just her active participation in women’s clubs. She demonstrated her leadership capabilities, her progressive spirit, and her commitment to gender equity by the way she lived her personal life. When Larrabee’s husband passed away suddenly in 1914, she “took charge of the family and of a considerable fortune embracing several enterprises and spanning properties in Washington, Oregon, and Montana” (Larrabee 2nd to Keegan).

This was by no means her introduction to business matters. In a time when men ruled the realm of business, Larrabee was a trustee of a vibrant company. The Larrabee family businesses were incorporated in 1900. The Articles of Incorporation of Pacific Realty Company are dated August 13, 1900, and Larrabee is listed as one of five trustees; the other four -- including her husband -- were men. The documents state that the five “are the trustees who shall manage the concerns of the company ..." (Articles of Incorporation).

In addition, in 1915, Larrabee made a land donation to the fledgling Washington State Parks Commission. It became the first State park in Washington. At that time, Larrabee signed the property transfer deed as President of Pacific Realty Company. And, when Larrabee and her son Charles donated 1,500 additional acres -- some 22 years later -- in order to increase the size of the park, Larrabee once again signed the deed as President of Pacific Realty Company.

And, if we understand feminist principles to mean basic gender equity, then Larrabee also demonstrated her belief in gender equity by the relationships she established within her extended family. Larrabee’s brother Jefferson Payne died in December 1924, leaving an estate of little value for his family, which included four daughters. Being well educated herself, Larrabee understood the need for a quality education, and she was determined that her nieces have opportunities to create their own career paths. Incorporated in the extensive support that Larrabee supplied for the Payne children were Stanford University educations for Helen and Frances Payne, as well as provisions for Adelia Payne to attend Mills College.

Politics and Women's Rights

Larrabee was interested in politics, but there is no evidence that she was tied to a particular ideology or was interested in political rhetoric. However, “her business obligations and social interests kept her very well-informed about local, state, and national political issues ..." (Larrabee 2nd to Keegan). And although Larrabee left no written utterance on the subject, her interest in her right to vote was at least inferred on two occasions. As previously noted, within the Monday Club, in February 1908, Larrabee participated in a discussion concerning women’s suffrage and co-education. In addition, Larrabee registered to vote as soon as she was eligible to do so under Washington state law. Washington women gained the right to vote in 1910.

Frances Larrabee voted for President Herbert Hoover, presidential candidate Alf Landon in 1936, and most likely for presidential candidate Wendell Willkie in 1940, all Republicans. Nevertheless, she and her son Charles “were hot supporters of New Dealing Governor Clarence Martin” of Washington State (Larrabee 2nd to Keegan). The reasons for Larrabee’s ardent support of Martin have not been delineated. However, Martin has been described as a fiscally conservative individual, as well someone who was deeply concerned about the welfare of less fortunate people. Larrabee demonstrated like attributes, and the fact that Martin was a member of the Democratic Party did not deter her from supporting him.

However, even though Larrabee was most interested in the soundness of political ideas and did not limit her favor to one political party, she did scrutinize individual politicians. This was demonstrated in a letter written to her son Ned in the late 1930s. The letter starts out discussing family issues and a valued employee who was ill. However, in the middle of the letter she inserts a comment related to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In a reference to Roosevelt’s attempt to increase the number of justices on the Supreme Court, Larrabee writes:

“Do you think President Roosevelt is going to get away with his last piece of effrontery? Were it any other man, I should not oppose part of his plan, for it has its good points. But I do not trust him at all, and it has all the look of just being done because he has not been able to get the decisions he wants out of the present members of the court. And it is ridiculous to make those men retire at seventy, unless they want to; most men of that caliber are at their best and most useful at that age” (Larrabee).

Roosevelt was in fact attempting to “pack” the Supreme Court. On May 27, 1935, a conservative majority on the court ruled that the National Industrial Recovery Act was unconstitutional, representing a blow to Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. This ruling was followed by court rulings against both the Agricultural Adjustment Act and New York’s minimum wage law. Roosevelt then proposed increasing to 15 the number of justices sitting on the court in order to have an opportunity for more friendly decisions.

The telling thing about Larrabee’s reaction is not that she so quickly understood what Roosevelt was attempting to do. Rather, she analyzed the political issues and saw both good and poor factors in the proposal, even though she had an obvious aversion to Roosevelt himself. And, as seen from her support of Washington’s Governor Martin, she was comfortable with the concept of New Deal programs. Her thoughts on these matters were certainly consistent with someone who did not adhere to specific political ideologies but formed her own opinions based on specific circumstances.

Steadfast and Loyal

Larrabee’s commitments to others were of much greater importance to her than were political ideologies as can be seen by her steadfast and long-lasting efforts in community building. She served her fellow congregational members in an active way until her death and was on the committee making arrangements for the 50th anniversary of St. James Presbyterian Church in 1938. Her membership in the Monday Club was also long lasting, and her name is sprinkled throughout that club’s records until she passed away.

But her most far-reaching enterprise was her involvement with the YWCA. When the YWCA building was dedicated on March 21, 1915, the Bellingham Herald noted that more than 450 people were present at the festivities and that the cost of the building was some $50,000, a princely sum at the time. Here again, Larrabee continued her service to an association until her death. During the 1920s and for at least half of the 1930s, Larrabee served as a member of the Board of Trustees. She was also one of a small number who served on the Nomination Committee, responsible for nominating new YWCA board members. In addition, she served on the Finance Committee in 1926 and 1929.

Minutes for the association’s Board of Director’s meeting of June 23, 1941 -- shortly after Frances Larrabee died -- show that “Mrs. Bartholick was appointed chairman of a committee to select a memorial honoring Mrs. C. X. Larrabee” (YWCA collection). Fittingly, the presiding board president was Mary B. Larrabee, Frances Larrabee’s daughter-in-law.

For the Good of the Community

Frances Payne Larrabee died at age 74 in June 1941. She was eulogized on the front page of The Bellingham Herald. The Herald stated: “Probably no other women in the Northwest worked more diligently and consistently for the civic and general good than Mrs. Larrabee” (The Bellingham Herald).

In addition to the civic commitments noted above, Larrabee was involved in the leadership of the Bellingham Woman’s Music Club, the Daughters of The American Revolution, and the Twentieth Century Club. In 1920, she was also the first elected president of the local American Legion Auxiliary. In addition, she was “the state chairman of American music for the Washington State Federation of Women’s clubs ... a past member of the Civic Music association ... a member of the Washington State Historical Society, the Colonial Dames, and of Pro America” (The Bellingham Herald). She also served for 45 years as president of the Women’s Missionary Society for the St. James Presbyterian church.

Nevertheless, although historians have well-chronicled the life and accomplishments of her husband, C. X. Larrabee, the history of Frances Payne Larrabee is told in sporadic vignettes. However, a combination of primary sources and secondary source vignettes prove that Larrabee’s dedication to community was legendary. Yes, Larrabee possessed considerable financial power, but she was unapologetic in the use of her financial recourses, as long as she felt she could benefit her community. Indeed, her endeavors went far beyond noblesse oblige. Larrabee’s impact on the populace of Whatcom County was immediate, dramatic, and enduring.