This reminiscence of Enumclaw in the 1920s and 1930s was written by James Edward Merritt (1920-2000). Jim Merritt was born on October 7, 1920, in South Prairie, Washington, the sixth child born to Frank and Emily (Morris) Merritt. His father, Frank, was a mine foreman for Morris Brothers Coal Mining Co., Inc. and Palmer Coking Coal Co., Inc. through most of his working career. Emily (Morris) Merritt was the fourth child born to George and Mary Ann (Williams) Morris, who emigrated from Wales, and sister to John H. Morris and Jonas Morris. Jim Merritt was first cousin to George, Jack, and Evan Morris, Betty Falk, and Pauline Kombol. Jim grew up in Enumclaw and served in the U.S. Navy during World War II. He graduated from the University of Washington with a degree in sociology. He was a social worker for the State of Oregon most of his working career. Jim married Emily Fergus in 1955 and together they had two children: Penelope and Fergus. Jim lived in Eugene, Oregon most of his adult life, where he later wrote his memoirs. This sketch of his early life in his hometown of Enumclaw originated as a chapter of his family history booklet Origins: Emily and Frank Merritt -- Their Story. Jim passed away on December 6, 2000, in Eugene, Oregon. Bill Kombol, first cousin once removed to Jim Merritt, assembled this story in 2007 from Jim Merritt’s original manuscript.

Enumclaw: My Home Town

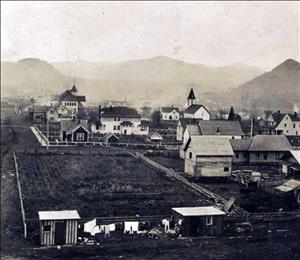

In looking back at Enumclaw, Washington, as it was in the days of my boyhood, I realize there have been countless changes. However, when I make an occasional visit as an elderly former resident, those parts of town that have not altered remain a delight to me still. Each brief visit results in flashes of memory, the highlights of the story of my youthful days.

In the shadow of Mt. Rainier, the city is located in the center of a natural plateau that approximates an area with a diameter of 30 miles.

From my kindergarten through twelfth grade years, 1926 to 1938, the population of the town hovered around the 2,500 mark. It served as the trading center of a surrounding community that included about 10,000 more persons. Lumber production and dairy farming were its major industries. Poultry raising and coal mining added to the community’s business. My father along with my mother’s brothers was involved in the local coal mines, which were located in the Black Diamond and Maple Valley area, a dozen or so miles from town.

I attended the JJ Smith Elementary School and Enumclaw High School. Between them they served around 1,200 or 1,300 students with a faculty of about 50. Before retiring, both Miss LeRoy, first grade teacher, and Miss Maginnis, seventh grade English teacher, had each taught almost three generations of Enumclaw’s students.

The resident population was dominated by Anglo-Saxons with a high proportion of Scandinavians. Other ethnic groups blended in well. There were no African Americans. A few Asians, all Japanese, were present in the lumbering, railroad, and mining camp areas. For the most part, they kept to themselves except for the younger members’ involvement in the local schools, where they were well accepted -- especially if they were good athletes.

Almost everyone in town knew, or at least knew something about, everybody else. Many were directly related. Many more were tangentially tied in with others -- e.g., “Roger Brown is a cousin of my Uncle Charlie.” The Banker, Newspaper Editor, the Mill owners, the Doctors, the Mayor, the Judge, and the Business owners were the town’s primary movers and shakers -- and typically, “The Old Boys’ System” kept fairly good control of local politics.

Except for business establishments there were no locked doors in Enumclaw. There was no such need. Unusual activity of any kind would be noted by one or another neighbor and everyone was aware of that fact. While intolerant attitudes may have been present in some families or groups, there was never any public behavior to reveal it.

Everyone had a good understanding of the main rituals of the community. Weddings followed similar patterns and were accompanied by songs such as “I Love You, Truly” and “Thine Alone” and gifts for the couple were left at the home of the bride’s parents. A rousing reception could be expected at a rented hall or a private home after the ceremony. When the bride and groom returned from their honeymoon, they were often surprised with a charivari arranged by their contemporaries. The friends would wait until they were assured that the newlyweds had retired for the night. They would then approach the couple’s home armed with every imaginable noisemaker, “awaken” them with the racket, and invite themselves in for a brief, rowdy celebration.

Certain of the town’s “matron-critics” always made careful note of wedding dates for possible future reference.

Funerals were solemn occasions at which the playing or singing of “Going Home,” “In the Garden,” and/or “Abide with Me” assured that there would be a fair amount of unconstrained sobbing. It was the custom to send flowers for the service and/or take food to the home of the bereaved. Often a home reception occurred after the burial at the cemetery. That gathering focused on the survivors and everyone’s memories of the deceased.

On Memorial Day and other special days it was common to attend to family graves at the cemetery and assure that their maintenance reflected proper respect for those who had “passed on.”

Here, again, the “matron-critics” took note of which cemetery plots were neglected.

All special occasions were recorded every Thursday in the Enumclaw Courier-Herald, the weekly newspaper. Society news was put together by the paper’s “Girl Friday,” who phoned every local subscriber each week to get news of family visitors and other happenings. The actions of town officials, school events, sport reports, and any news of direct concern to the community was featured. The publisher-editor was a member of a local pioneer family and was well acquainted with everyone in town.

The Seattle Times, Post-Intelligencer, or Star were the big city newspapers. Most subscribed to the Times with its news of Seattle, the area, and the nation. All were entertained by Little Orphan Annie, Moon Mullins, Toonerville Trolley, Joe Palooka, Maggie and Jiggs, Winnie Winkle, Ella Cinders, Dick Tracy, and other comics. (My favorite character was “The Terrible-Tempered Mr. Bang” in Toonerville Trolley).

The Sunday paper featured a Rotogravure Section of brown-toned photographs of activities or areas of interest in the region. When very special events occurred between paper deliveries, an occasional extra edition was printed and newsboys came throughout the neighborhoods with shouts of “Extra! Extra!” followed by a mumbled, indecipherable revelation of the happening.

Married women rarely held jobs unless they were widows or were supporting a disabled husband. Virtually all female teachers were single. Women worked as store clerks, secretaries, teachers, nurses, and telephone operators. Whatever their circumstances, the salaries paid to women were very much lower than those paid to men.

My sisters Grace, Emily, and Marian and my Aunt Beatrice all worked as telephone operators at one time or another. Each was “hit on” by fellow male employees who held superior positions. And each had her own way of warding off such undesired proposals. In the male-dominated atmosphere of those days, the inequality of the sexes was rarely, if ever, questioned. What a wonderful difference today’s growing balance between the sexes might have made.

Almost every household had a telephone or the use of one. Long distance calls were uncommon and, in most instances, meant an extreme emergency. The telephone instrument was always black and was usually attached to a wall. All calls were made through the local telephone operators. If you wanted to call the Merritts, you asked for 3-J. Virtually all telephones at the time were on a 2- or 3- party line.

Commonly Monday was Wash Day; Tuesday was Ironing Day; and other days of the week usually called for some special housekeeping or cooking function. The washing was hung outside, on the porch, or in the basement on clotheslines to dry. Almost all clothing made of the various materials of that day required ironing. Non-washable items were cleaned in carbon tetrachloride, which had an odor not unlike gasoline but considerably stronger. In later years the use of that product was found to be harmful and exceptionally dangerous.

In many homes an annual Spring Cleaning took place. That meant scrubbing the house from top to bottom and cleaning rugs, drapes, mattresses, furniture, and all household items. It was a time when combined, pungent odors were prevalent in the household. And a good time to steer clear if you were not directly involved.

Late summer was canning season when the various local fresh fruits, berries, and vegetables were put up and sealed in pint and quart jars for consumption during the winter. It was the one time that the wood stove was fired up on hot summer days.

Enumclaw was a “walking town.” Those with autos were primarily “one-car families” and a two-car garage was unheard of. For a long time there was no choice of colors among automobiles. Black dominated. When color option became prevalent, various shades of red took over in Enumclaw for a while.

Youthful drivers gained the privilege of occasional use of the family car. For a teenager to have a car of his or her own was beyond consideration. The parking area near the High School held eight or 10 automobiles at most on school days. As a rule only one of the cars might be that of a student who had missed the school bus.

Any distance that required the use of a car was usually referred to as a trip. The nearest large cities were Seattle, 35 or 40 miles away, and Tacoma, almost 35 miles, and a visit to either one entailed an all day excursion. The highway system was poorly developed and roads between towns, while often black-topped or paved, had frequent sharp curves or series of curves. I was always excited when my mother and older family members took a trip to Seattle or Tacoma for a day of shopping. Those who remained at home were always remembered with little surprise gifts.

Nearly all the businesses in town were locally owned and most merchants allowed charge accounts. All bills came at the end of the month and were payable either by mail or at the store, itself. Swain’s grocery store always provided a free sack of hard candy at the time of payment.

Bottled milk was delivered to most households along with eggs and other dairy products by one of the town’s three dairies. The Iceman delivered ice once or twice a week for families with ice boxes. Some grocery stores took orders over the phone each morning and delivered in the afternoon.

Meat markets were separate from grocery stores. Most fresh cuts of meat were displayed in the butcher shops and nothing was prepackaged. Lard was sold by the butcher in 5 and 10 pounds tins, which later made great little buckets. When Prohibition ended, the little buckets could be taken to the local taverns to be filled with beer. They were then referred to as “Growlers.”

In general, each shop in town specialized in particular items and none had self-service. Customers were waited upon by the store’s staff. In grocery stores a clerk had a pad on which he/she wrote down the customer’s order. The clerk then went around the store collecting the requested items, pricing them on the pad, bringing them to the counter, and bagging or boxing them. The prices were totaled on a hand-operated adding machine and the total was rung up on the cash register. The clerk then assisted the customer with loading the groceries into a car, when appropriate.

Many items such as flour, sugar, pickles, sauerkraut, and peanut butter were weighed out in bulk. The latter three items were packed in the type of waxy paper cartons now used for "Chinese ‘take-out." Cheese was cut off in wedges from a large wheel of cheese. Bacon was sliced to order from a big slab. Wieners were sold by the count and removed from a seemingly endless string of wieners.

Many produce items were originally sold by count and, later, by the pound. By today’s designation, most all fruits and vegetables would have been considered “organic.” Throughout much of the year they were provided to Enumclaw’s stores from truck farms in our neighboring Puyallup and Kent Valleys west of town.

The stores were open six days a week and their normal hours were 8:00 to 5:30. On Saturdays, the afternoon closing time was extended a half hour as most of the outlying farmers did their once a week shopping on that day. I remember well the busy Saturday I was clerking at a local grocery store. I overlooked a 25-pound sack of potatoes that was to have been loaded in Mr. and Mrs. Barillas’ car. They were very nice about the oversight, but Bill Murray, the store manager, didn’t let up on his 15-year old employee for the next six or eight weeks.

Enumclaw had six churches: Presbyterian, Danish Lutheran, Trinity Lutheran, Gospel Tabernacle, Christian Science, and Sacred Heart Catholic Church. One of the ministers was rumored to do a little “diddling” on the side and the priest was overly fond of his sacramental wine but, while quite widely known, these occurrences never became big issues. For some people church was the center of their social activities and young people’s groups were sponsored by most of the denominations.

My family followed the general dictates of the Protestant Christian religion but had no direct church affiliation. My mother always claimed that she liberally supported all the churches in town by attending their annual bazaars, special teas, and fairs. My sister, Marian, taught Sunday school at the Presbyterian Church and, for a short while, I attended another person’s class there. I quit when my Sunday school teacher failed to keep track of the fact that I had attended 13 Sundays in a row. I was supposed to receive a bronze pin for that act of loyalty. When I didn’t get it, I said “to heck with it” (in those days that was my strongest expletive) and, despite entreaties that, if I returned “they would make things right,” I didn’t give them a second chance. I hadn’t really been impressed with Sunday school, anyhow.

Several brotherhood, fraternal, veterans’, business, and grange organizations provided social outlets for people in the community, as well. The fraternal groups had youth organizations. Later, Union organizations were started.

The community of Enumclaw was interested in highlighting local culture and sponsored an annual “Music Week” to showcase local talent. The five weeknight programs were carefully put together to assure that soloists who were competitive didn’t end up on the same program. “The End of a Perfect Day,” “The Holy City,” “Londonderry Air,” “To a Wild Rose,” “The Sunshine of Your Smile,” several “Mother” songs, some Strauss waltzes, and a few other light classics were repeated annually to the enjoyment of all. One of my buddies and I attended the concerts regularly. We would always sit in the back seats as, all too often when a local diva would perform, one or both of us would get a strong urge to giggle and we would have to make an early departure.

Wind-up Victrolas gave an opportunity to listen to some classics recorded by Madame Schumann-Heinke and Caruso as well as some old so-called comedy records. They were used mostly, of course, to listen to the popular songs of the day. The single play fragile “platters” generally had a hit song on one side and a less known tune on the other. The wind-ups were gradually replaced by electric phonographs, which were often combined with radios.

Radios were originally introduced as “Crystal Sets.” Later, tube sets appeared but, at first, they came only in large cabinet (console) models. Then came “table-top” models. The ownership of one radio per household was common. For a long time, even that was considered special.

Families grouped around the console when popular programs were broadcast. On a summer evening it was often possible to walk along any street in the town and listen to the current Joe Louis boxing match through the open doors of the houses. And, on particular nights, you would never consider telephoning anyone during the “Amos ‘n Andy” or “One Man’s Family” hour. “Little Orphan Annie” was a favorite kids’ program and came on just prior to dinner (or “supper” as it was called by many).

From my point of view, the ultimate pleasure was to have a player piano where everyone could stand around, read the words written on the piano rolls, and give joyful full-throat to favorite tunes. My grandparents had such an instrument and it provided me with countless hours of absolute delight. How I loved to sit, pumping the piano, raising my voice to the music. My Welsh grandmother, an invalid in her later years, would almost always join me singing in her wonderful alto voice.

The Liberty Theatre was the showplace for all the Silent Movies. A large theater organ was played to accompany each feature in underscoring the mood of the movie. Later, after “Talkies” arrived, Mr. Groesbeck, the local theatre owner, opened the Avalon Theatre. There was a change of shows about three times weekly unless, of course, a big hit came to town and would run five days instead of the usual two or three. Short subjects and newsreels were a part of every movie program in those days. Every Saturday there was a kids’ matinee, which included “serials” that ran from week to week. How we loved the exciting adventures of Tarzan!

Adult organized youth programs such as the Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, Campfire Girls, Friendly Indians, and the Future Farmers of America were offered in the community. For many of us, such “grown up directed” programs were too similar to school and classroom projects. We tried them out and decided against them.

There were no public playgrounds. I don’t recall that there were any swings or teeter-totters even on the school grounds. Scattered throughout the various neighborhoods many backyards had simple parent-built play equipment, none of which had been acquired as “ready-mades.” All were made of heavy lumber frames and the tire swings, bag swings, and plank seat swings hung from sturdy rope or chains. A teeter-totter usually stood separately.

Most of the youngsters in town got together in their neighborhood groups and set up their own activities. Old pieces of lumber and cardboard were awkwardly constructed to become clubhouses or, sometimes, tree houses. Sandboxes throughout the neighborhood became racetracks for little cars, battle grounds for cowboys and Indians, or the settings to re-enact the latest Fu Manchu or Tarzan movies.

Group games such as Run-Sheep-Run, Kick-the-Can, Duck-on-the-Rock, Cops-and-Robbers, Red Rover, and other variations of Tag and Hide-and-Seek were common on early evenings. In the spring and summer the “immies,” “shooters,” and “steelies” came out for endless marble competitions. Mumble-peg, too, was a favorite as long as a good pocket knife was available. A rousing hop-scotch game or jump rope competition, if it was wild enough, would involve boys as well as girls.

Large group activities included both girls and boys. While the guys were doing “boy’s things,” the girls were usually playing house or parading around in grown-up dresses and cast-off costume jewelry. Girls joined in sandlot baseball games, which were played with softer-type indoor baseballs. Females were rarely included in pick-up football or basketball games, however.

With our prized clamp-on roller skates, tightened with our skate-keys, everyone took part in rolling along on the sidewalks with care to avoid big cracks and uneven spots. Even more wonderful was playing improvised hockey on the tennis courts until we were kicked off before we “ruined the surface.” Those who had bicycles used them to ride from one place to another and not as group activities.

With the lower foothills of the Cascades framing a portion of the town and not too far from it, the guys would occasionally turn their attention to planning adventurous hikes. Arranging an early morning get-together, each would pack a lunch (a peanut butter or baloney sandwich along with an apple or orange and whatever candy could be scrounged) and head for the “hills.” The day would be spent rolling small boulders down the hillside or damming up a little creek to form a small pool for “skinny-dipping.”

Inclement weather switched interests to indoor pastimes. Two or three of the homes in our neighborhood had full basements, which gave opportunity for get-togethers. Simple card games, board games, and word games were good for two or three hours of attention. Collections of Tinker Toys, Erector Sets, and Building Blocks along with cardboard boxes, empty Quaker Oats cartons, short lengths of cord or string, empty spools, and large buttons from our mothers’ various button boxes were good for assembling serious or wildly imaginative projects.

The latter frequently included designs for stick-and-newspaper kites, which rarely got off the ground.

On a few occasions there were guilty little giggly sessions in which off-color jokes that we had overheard were repeated. With often little understanding of the jokes, themselves, but delight in saying some naughty words, we could whomp up a near hysteria of laughter. We had a session or two, as well, displaying genitalia, talking about sexual differences and whether all girls and boys of different races were similarly equipped. But, mostly, when sharing was the activity of the day, we verbalized our dreams concerning the future and what we were going to be and do when we grew up. Oh, what fabulous characters were in the making! (More important, what a wonderful group of characters we were then!)

The Olsons' basement was the ideal setting for the preparations for “Giving a Show.” Our planned musicals and melodramas rarely gained an audience but they provided hours, even days, of rehearsing and improvising to keep us busily occupied. This was my favorite among the various activities as I was enthusiastic about all forms of theater and had aspirations to be an actor when I grew up.

The movies were often considered as examples of worldly sophistication and set many fads and fashions. Cigarette, cigar, and pipe smoking added drama and significance to many theatrical scenes. And the use of tobacco, by men especially, was generally accepted. As popular actresses started using cigarettes as “props” for their characterizations, women’s public smoking became more tolerated.

Use of tobacco was regarded as being “sinful,” based on some vague religious reasons that were ignored by all smokers. All the men in the family smoked cigarettes. Neither my four sisters nor my mother ever took up smoking. I started when I was about 20 years old because a part I had in a college play required it. (It was not until the late 1950s and early 1960s that medical research condemned the use of tobacco because of its danger to health.)

Medical care in Enumclaw was provided by Drs. Ullman, DeMerchant, and Staley. They shared offices in a building near the center of town and, when appropriate, made home calls. They maintained a couple of sick bay rooms that were overseen by Mrs. Hack, everybody’s favorite nurse.

Dr. Tiffin practiced in a separate office and offered regular medical care as well as something called “Physio-Therapeutic Treatments,” which featured an X-Ray and Ultra Violet Ray approach.

The Farmers’ Picnic Grounds, a park-like grove of trees under which were many permanently built picnic tables, stood about two miles out of town. In the 1920s and early 1930s it was the focal point of most of the town’s summer celebrations. It had a well laid out baseball diamond, a covered, but open air, dance hall, a small bandstand, and a well built permanent refreshment stand. There was a cleared strip that could accommodate a small “fairway” for setting up display booths for local organizations. It was used too as a space for small carnivals that usually included pony rides, little merry-go-rounds, a “prize everytime” fishpond, and some “test-your-skill” booths with their shelves of feathered kewpie dolls.

On the day of an event a member of our family group was often sent out early in the morning to save adjoining big tables for our combined families. Later the table was loaded with platters of fried chicken, heaps of potato salads and slaws, favorite casseroles, home-baked breads, rolls, desserts, melons, other fresh fruit, and a couple of hand-turned freezers filled with rich homemade ice creams.

How I looked forward to these events! Not long after our family had set up our part of the picnic table, my father would always fill one of my hands with small coins. I was then eager to get together with my cousins, Evan and Betty, who would also have their “handful of change.” We would then wander back and forth on the fairway giving profoundly serious consideration to how and where we would spend our few dimes and nickels that afternoon.

The sounds that accompanied us as we strolled the area were the enticements we had to deal with: the shrill, rousing, slightly off-key notes of the merry-go-round’s calliope; the occasional neighing of the bored little ponies at the pony ride; the gruff, hoarse, seductive voices of the barkers in the skill booths; and the frightened cries of younger kids whose parents had introduced them to the rides prematurely.

Finally, our minds would be made up. Then, of course, we would follow the usual pattern of our previous visits. A ride or two on the carousel and catching a numbered fish to win a little prize at the fish pond would take care of most of our coins. With our last couple of nickels we would be off to the refreshment stand to stand in line for a “store-bought” ice cream cone, a Kid Brother or Baby Ruth candy bar, or a nickel’s worth of “penny candy.”

The Fourth of July celebrations always featured the city band, a prominent speaker from county or state government, local competing baseball teams, and an evening dance. All this to the accompaniment of a staccato of firecrackers that ran the gamut of ladyfingers to good-sized noisemakers. Sparklers, cherry bombs, roman candles, skyrockets, smoke bombs, and snake-like novelties added both to the spectacle and the danger of the available fireworks. I was allowed to have a few sparklers and smaller-type firecrackers.

Each occasion was usually discussed in the days following by an assessment of “who danced a lot with whom and how serious they seemed to be.” And “who got a bit too high and had a fist fight with whom following or during the baseball game.”

Nobody ever referred to getting in touch with an officer of the law. Everyone just mentioned the name Tom Smith, the town Marshal, when trouble was to be handled. He was known to all and he and his deputy, Mr. Francisco, had a line on everybody. Tom, despite his gruff demeanor, was actually a kindly caretaker of the entire community. He and the local state troopers looked after the young weekend revelers and “straightened them out” with a minimum of fuss and community involvement. Tom Smith was regarded throughout the county and much of the state as a shrewd, canny lawman and was credited with picking up several renegades who made the mistake of passing through Enumclaw.

City Hall was a small, one-story brick building in a park-like setting that took up a square block area. It housed the city offices, a small jail, and an office courtroom. The entire community voted there. Its rear half housed the fire station, which was manned by volunteer firefighters and the fire siren was tested every Saturday at noontime.

The structure was located a block away from the town’s main intersection. Placed throughout its surrounding lawn and shrubs were a few benches and, conspicuously in one corner, was a small artificial pool that was stocked with large rainbow trout. In one segment of the knee-high granite-rock wall surrounding the pool was a constantly flowing drinking fountain with the most delicious, icy spring water to be found anywhere.

Enumclaw was a community whose residents participated actively in all civic affairs and was delighted at any opportunity to welcome visitors and show off their well maintained neighborhoods. Blending into adjoining foothills, it enjoyed the dominance of glorious Mount Rainier. What an indelibly memorable combination -- a magnificent, majestic mountain, a proud, hospitable town, and a young boy who loved them dearly.