Chehalis, the seat of Lewis County and long a commercial center for area farmers and loggers, grew out of claim settled in 1850 by Schuyler (1810-1860) and Eliza (1826-1900) Saunders near the confluence of the Newaukum and Chehalis rivers. Known then as Saunders' Bottom because of its marshy ground, Chehalis gained footing as a town once the Northern Pacific Railroad established a depot there in 1873. Over the years, local residents have built a town with a varied economy, relying on logging, mining, farming, small industry, retail, and residents and businesses that Interstate 5 brought to town. Adaptation to changing circumstances has been a strength of the community, particularly in the last 50 years as the economy has experienced a fundamental shift away from relying on natural resources. (Note that the name Chehalis was given to a Washington county organized in 1854. In 1915 that county was renamed Grays Harbor County.)

First Peoples

Prior to white settlement both the Upper Chehalis Indians and the Taidnapam band of the Cowlitz Indians lived in the area around what is now Chehalis, though they do not appear to have had permanent villages there. It lies between the traditional territories of those groups and along the Chehalis River, which they used extensively for canoe travel. The route followed by State Highway 12 today follows a long-used route followed by Upper Chehalis and Cowlitz to trade with the Yakama Indians on the east side of the Cascades.

Neither the Cowlitz not the Upper Chehalis signed treaties with the United States. The Upper Chehalis joined the Lower Chehalis (a related, but distinct group) on the Consolidated Tribes of the Chehalis reservation, created by Secretary of the Interior J.P. Usher, near Oakville in 1864. The federal government did not recognize the Cowlitz tribe until 2002.

The fact that the tribes had not ceded their land did not prevent white settlers from filing claims. Many Americans filed claims to lands in the Chehalis River valley and its tributaries' valleys prior to 1864. Direct conflict between the Indians and the new arrivals did not ensue. This may because epidemics had decimated the tribal populations in the early part of the nineteenth century, reducing its need for territory. Also, many of the Indians had developed working and trading relationships with settlers passing through on their way to Puget Sound.

First Settlers

The first white settlers at the confluence of the Chehalis and Newaukum Rivers, Schuyler and Eliza Saunders, from New York and Ireland respectively, arrived in 1850. They built a farm on land they would later claim under the Donation Land Act of 1850. Their contact with local Indians seems to have been limited. They also lived for nine years without any nearby white neighbors. Settlements in the area, such as Claquato located upstream on the Chehalis River and Fords and Skookumchuck prairies (later Centralia), grew up within a few miles of the Saunders.

For some time the most attention the area around Saunders' claim attracted related to its sogginess. A review of trail conditions published in the Pioneer and Democrat explains why the area gained the moniker "Saunders' Bottom." Beginning at Wet Prairie, about four miles north of the Saunders' conditions were nearly impassable: "after travelling four miles of bad road, through mud above your horse's knees, you come out of the woods at Mr. Saunders'."

Difficult transportation stymied economic development. The Chehalis River flowed to the ocean, whereas the primary market for the region, New Market, lay on Puget Sound to the north. The "road" to New Market was little more than a trail, and barely passable when wet. Fallen trees blocked trails through the hills that bordered the valley, so most travelers stayed on the prairies and forded the wet areas.

The river assisted in transporting goods by canoe only as far as Fords Prairie, at which point it turned west and farmers loaded their produce into wagons for the overland trip to New Market. In 1866, J. T. Browning started a steamer service along the Chehalis River. He followed the river down to the Black River where he turned upstream to Shotwell's Landing. From there freight went by wagon overland for 10 miles to Olympia. The trip, extensive either by canoe and wagon or steamer and wagon, limited the settlers' involvement in the cash economy, which in turn limited the area's development.

Still, the open prairies along the primary overland route between Portland and Puget Sound attracted settlers. Once they laid tiles and dug ditches to drain their land, it made excellent farmland that produced bountiful crops and supported livestock well.

One family, Obadiah B. McFadden (1814-1875), chief justice of the territorial Supreme Court, and his wife Margaret (b. 1819), bought the southern half of the Saunders' claim in 1859. The house they built on their land still stands and is the oldest structure in Lewis County.

From Farm to Town

The Saunders divorced in 1859, just a year before Schuyler died, and Eliza retained her title to the northern half of their claim. Through her control of that land she would shape Chehalis' growth for its first 20 years. Several other factors would need to fall into place before that town would emerge, however.

In order for a town to develop, it needed a resident with a strong desire to build it. William West (1839-1915), who arrived with his wife Elizabeth (b. 1830), his oldest son Robert, and his brother-in-law John Dobson (1841-1907) in 1864, would be that resident. The Wests bought 160 acres from a homesteader and began farming. At first William focused on making a living and building up his farm. Later he would help get the Northern Pacific Railroad station for Chehalis, invest in the joint stock company formed to build the first warehouse in town, help organize the school district, serve as county auditor, county treasurer, and deputy sheriff, serve on the Chehalis City Council, steer the effort to have the county seat moved to town, and help found the town's Episcopal church.

But before West could unleash his energies, he needed a town. Not much had changed in the 13 years since the Saunders' arrival. Transportation routes remained limited by the area's swampy conditions and its lack of roads. A military road built in the late 1850s bypassed Saunders' Bottom to avoid mud and muck. McFadden had raised a subscription to clear and corduroy (a method of road building that involved laying logs across the road to form a solid surface) a road through Saunders' Bottom in 1863. But even given new routes, traveling to New Market still required at least an arduous day.

When William West brought in his first crop and had processed his hogs into ham and bacon, he went Olympia to trade. He sold to local merchants and then approached someone selling a plow. In his reminiscences written for the Chehalis Bee-Nugget, West recounted how he purchased that plow:

"There was only one plow in town for sale and the merchant would not take my bacon in pay for it, only wanting hams, which were not enough. In looking about town I stated my case to Captain Percival, who kept a store, and he offered to take my eggs, bacon and other produce and get me the plow, and would also pay cash for my extra produce over and above the amount of my purchases, so I got the much needed plow and Captain Percival gained a customer who dealt with him as long as he lived" ("Historical Incidents of Early Days in Lewis County").

The transaction highlights the scarcity of both cash and equipment in the early days.

Getting a Depot the Hard Way

In 1870, McFadden took over the post office Schuyler Saunders had established at his house in 1858. He changed the name to Chehalis, which the state legislature recognized in 1879.

In 1873, the single most important factor in Chehalis' development arrived: the Northern Pacific Railroad (NPRR). The railroad, which would eventually stretch across the country, had only managed to lay track from Kalama on the Columbia River to Puget Sound, but that bit of rail connected the Chehalis valley to ocean-going ports and markets for their produce.

The tracks crossed the Saunders' claim and Superintendent J. W. Sprague talked with Eliza Saunders about a land donation for a railroad depot. The depot would have provided a nucleus for a town, raising local land values significantly, but Saunders refused the deal offered. Unwilling to pay more for land for a depot, Sprague simply chose another site up the nearby hill at Newaukum.

Newaukum lay three miles south of Chehalis, across the marshy ground and up a hill with no road between the two. Chehalins did not know that Sprague had purchased the property and thought they could still persuade him to locate at Chehalis. A group of men took a petition explaining the difficulty residents would face crossing the lowlands and climbing the hill to Spraque in Kalama. Just to catch the train to Kalama, the petitioners had to walk on the railroad trestle to avoid sinking into the muddy ground.

Sprague, having invested in Newaukum land, had no interest in moving the depot and refused the petition. The group met again in Chehalis and someone, most likely McFadden because of his law background, according to historian Robert R. Weyeneth, pointed out that trains had to stop for a red flag. They attempted this, and the train stopped. After some time of raising a red flag daily, the railroad relented and added Chehalis to the scheduled stops.

Becoming County Seat

Having a railroad connection to Puget Sound and the Columbia River opened markets for Chehalis farmers and businesses. A group of businessmen, including William West and John Dobson, formed a joint stock company. They built a trackside warehouse, the first building in Chehalis. George Hogue, who owned a store in Claquato, opened a branch next to the warehouse and in 1874 the county seat moved from Claquato to Chehalis.

Claquato did not give up the county seat without a fight, but it did not have much to counter Chehalis' advantages. The railroad had bypassed Claquato and its residents and business owners did not have the capital to match the Chehalins' willingness to pay $2,000 of the $3,000 cost of building a courthouse. The state legislature weighed its options and chose Chehalis.

These early buildings sat on land originally held by Eliza Saunders on Main Street around the railroad tracks. She slowly platted lots and sold them, first in 1873, then some more in 1881-1883 and 1888-1893. West would later criticize her unwillingness to sell because it hampered the town's growth. Several histories of Chehalis cite bad business deals involving business associates and one of her husbands (she married four times) as the reason for her reluctance to move quickly in platting the town.

As the town grew, more businesses came to town to capitalize on the surrounding area's resources. Farmers grew hops that they sold in Europe. Other farmers brought in wheat for milling and shipping out on the railroads. In 1878 William West and John Dobson opened a packinghouse for butchering livestock. They sent pork and no doubt other meat on the railroad to Portland and Victoria, British Columbia.

The 1880s brought incorporation (1883), a sash and door factory, the Chehalis Nugget newspaper, the Superior Coal Mine (which operated in town, where Chamber Way is now), a tin shop, sawmills, shingle mills, and a brickyard.

Market Town

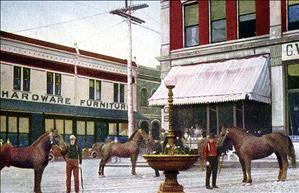

The prairie lands in the Chehalis valley filled with settlers quickly and new settlers filed claims in the surrounding valleys. Chehalis served as an outfitting center as well as a market town. Gus Temple, whose family farmed the Tilton Valley recalled going through Chehalis in 1884 for a 1937 article in the Lewis County Advocate. Temple and his father purchased provisions for their claim and, “packed them on a pony, a process that attracted very little attention in Chehalis in those days, as pack horses could be seen on the street most any time.”

Yet the town did have more cosmopolitan elements. The Tynan Opera House, built by Eliza (Saunders) Barrett, whose maiden name had been Tynan; a Catholic school for girls; the courthouse; a few churches; and a school had also been built.

Changes and Setbacks

The 1890s brought rapid change to the town. In 1892, two suspicious fires burned the downtown area that had originally included Barrett’s land, including her business block, built in 1891. In the previous three years the Chehalis Land and Timber Company (in which West and a number of other local businessmen had invested) had developed a number of lots along Market Street north of the town’s original core. They had built commercial buildings and a hotel in the area around Boisfort Street. After the fires, the town center shifted to Market Street and future development grew from there.

Just after the fires, the Panic of 1893 brought an economic depression that lasted several years. Logging declined because of decreased demand nationally for lumber products. This in turn slowed the development of new farmland because logging opened up new land, drawing in new settlers. Along with logging, the sawmills and wood-products companies slowed.

Twentieth Century Chehalis

By the turn of the century, Chehalis had found its feet again. About 2,300 people lived in town and “macadamized and plank roads extend[ed] for miles into the county in every direction” (“Lewis County, Washington”). The Chehalis Valley Creamery, started in 1896, processed milk from area farms and sold it in Tacoma and Seattle. The coal mines and mills produced raw materials that shipped out over the rails.

In the years before the Depression lumbering, dairying, and other farm production dominated Chehalis’ economy. Factories in town included The Pacific Coast Condensed Milk Company, Palmer Lumber and Manufacturing, Shaw’s Cigar Factory, Simmons Glove Factory, and the Pacific Tank and Silo Company.

In 1915 the Lewis County Cannery Association formed to build a cannery for processing vegetables grown on area farms. Later, in 1928, the National Fruit Canning Company bought the Lewis County Berry Growers Cannery. National is still in business, processing vegetables. The opening of the White Pass Highway in 1951 made it possible for National and other processors in Chehalis to get fruits and vegetables from Eastern Washington and can or freeze them for market, benefiting both the processors and the farmers.

In addition to lumbering and wood products, the forest supplied another Chehalis industry. I. P. Callison and Sons, founded in 1903, paid local independent harvesters for cascara bark, which was used as a laxative. Once synthetic ingredients replaced cascara bark in medicines, the company shifted production to peppermint and spearmint oils, which they continue to supply to customers worldwide. Other branches of the company have sold ferns, salal, and digitalis.

During the Great Depression, Chehalis saw declines in lumbering and markets for agricultural products, but largely managed to support themselves because of all of the local agriculture until World War II again increased demand for goods and raw materials produced in Lewis County.

War Years

During the war demand for lumber, according to William B. Greeley, a former head of the Forest Service, “so thoroughly absorbed all the energies of the West Coast lumber industry ... that for all practical purposes we are part of the Armed Services” (Ficken, 224). Loggers were not drafted because their work was essential to the war effort.

Boeing operated branch plants in five towns in Washington because the work force in Seattle could not produce all the airplanes needed by the military. One opened in Chehalis, where the Lewis County Public Utility District building is today. Local workers, many of them women, built pilot and copilot seats, wings, lower turret mounting assemblies, and interspar ribs for B-17 and B-29 bombers.

The end of World War II marked a turning point in Chehalis’ economy and way of life. After the war, lumber on private lands was depleted and what timber was cut went more often to pulp and paper mills rather than local sawmills. Those mills employed thousands before they closed due to a decreased supply of timber and a shift in the size of the timber as the older, larger trees gave way to younger, smaller ones. The shift to federal lands opened new forests to cutting, but later environmental concerns have restricted cutting on those lands as well.

In the post-war years Lewis County’s economy lagged behind the rest of the state, which gained new industries based on defense spending during the Cold War. To increase year-round employment, Chehalins worked to shift the basis of the economy from lumber and agriculture to industry.

New Opportunities and More Changes

The new U.S. 99 expressway (later re-named Interstate 5) opened in 1955 and though it bypassed downtown Chehalis, it connected Chehalis to Puget Sound and Portland. This increased the number of travelers passing through the area and helped Chehalis capitalize again on its position between the major metropolitan areas and along the primary transportation route.

In 1956 the Chehalis Industrial Commission, a private corporation, formed to promote the Chehalis Industrial Park. They purchased land near the freeway and went to great lengths to encourage companies to locate their businesses in the park. In March 1957, to entice Goodyear to bring its tread rubber factory to Chehalis, volunteers spent two weekends laying 3,500 feet of rail for a spur line from the main railroad lines to the park. Local businessowners sold railroad ties at four dollars a piece to fund the effort, which was successful. The industrial park is now operated by the Port of Chehalis.

More recently, the Chehalis-Centralia area has gained a number of distribution facilities. Fred Meyer Stores has a 1.5-million-square-foot warehouse, which stores goods that are shipped to area Fred Meyer stores. Their locations midway between the Puget Sound and Portland metropolitan areas make Chehalis and Centralia ideal for efficient distribution of large amounts of consumer goods.

Today Chehalis is a community of more than 7,000 people. Recent flooding has led to much discussion about how and where to grow the town that has attracted commuter population. As in the past, adaptation to new circumstances will be key to helping the town prosper.