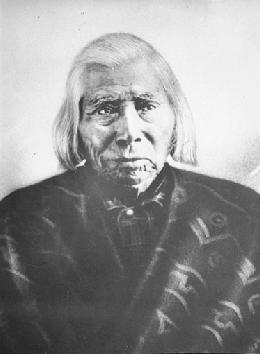

Chief Spokane Garry was a chief of the Spokane Tribe whose long, and ultimately tragic life spanned the fur-trading, missionary, and white settlement eras of the region. His father, also a Spokane chief, sent Garry off with fur traders at age 14 to be educated at the Red River Settlement's missionary school in Canada. Garry returned after five years, fluent in English and French, to become an influential leader and spokesman for his tribe. He opened a rough school to teach reading and writing and also taught his fellow tribesmen agricultural techniques. He participated in many peace councils, including those of 1855 and 1858, and was known as a steadfast advocate of peace and an equally steadfast advocate of a fair land settlement for his tribe. He never wavered on his insistence that the Spokane people should have the rights to their native lands along the Spokane River, a goal which proved unattainable. His own farm in what is now the Hillyard area of Spokane was stolen from him late in life and he and his sadly diminished band were forced to camp in Hangman Valley, where boys from the growing city of Spokane would throw rocks onto their tepees. A kindly landowner allowed Garry and his family to camp in Indian Canyon, where he lived out the rest of his life in poverty. He died there in 1892 and was buried in a pauper's grave. Decades later, a Spokane city park was named after him and a statue erected in his honor.

Son of a Chief

Spokane Garry was born around 1811, the son of Illum Spokanee (sometimes spelled Illim or Illeeum, d. 1828), a chief of the Spokane Tribe. Garry's original Spokane Salish name was Slough-Keetcha; he acquired the English name Garry because of a remarkable set of circumstances when he was about 14.

In 1825, George Simpson (1792-1860), a governor of the Hudson's Bay Company, called a meeting with Illum Spokanee and the chiefs of seven other tribes at Spokane House, the company's trading post. Simpson told the chiefs he wanted to send some Indian boys to be educated at the Red River Settlement's missionary school near present-day Winnipeg. Simpson was putting into practice the ideas of John West (d. 1845) , an Englishman who established the mission school at Red River to educate the tribes and lead them to Christianity.

"He (West) looked upon the Indian child as the leader of this wandering race -- and his education as the best means of reaching its adult members," wrote William Bertal Heeney in the book John West and his Red River Mission.

Simpson wanted the boys to return home after their schooling and spread Western-style civilization among the tribes. Two chiefs, Illum Spokanee and a Kootenai chief, surprised Simpson with their response. They each offered to send one of their own children.

"Bring Them Back to Us"

Alexander Ross (1783-1856), a Hudson's Bay employee, later wrote that one of the chiefs stood up and said, "You see, we have given you our children, not our servants, or our slaves, but our own. We have given you our hearts -- our children are our hearts -- but bring them back to us before they become white men" (Ross).

A few days later, the two boys were baptized and given new names. One was named Kootenai Pelly, after a Hudson's Bay governor, and the other was called Spokane Garry, after Nicholas Garry (d. 1856), a director of the company.

The two boys left with the Hudson's Bay fur brigade on April 12, 1825, and made the arduous trek across the Canadian Rockies and the prairies. At the Red River Settlement, Garry learned to speak, read, and write English and French. He also learned math and agriculture and became a Bible-quoting Christian.

At the Missionary School

The school was organized on strict Anglican-boarding-school lines, yet Simpson had made it clear that Garry and Pelly were to be treated well. "Let me entreat that the utmost care be taken of the two boys 'Pelly' and 'Garry' brought by me from the Columbia this summer," wrote Simpson to the reverend in charge of the school. "They are the sons of two chiefs of considerable influence and any accident to them would be likely to involve us in eternal warfare with their tribes, which are very powerful" (Jessett).

David Douglas (1799-1834), the famous botanist, visited the school in 1827 and met Spokane Garry. "Had a visit paid me by Spokane Garry, an Indian boy, native of the Columbia, who is receiving his education at the Missionary School," wrote Douglas in his journals. "He came to inquire of his father and brothers, whom I saw; he speaks good English; his mother tongue (Spokane) he has nearly forgotten" (Douglas).

Garry and Pelly returned home briefly in 1829, after they learned that Illum Spokanee had died, but soon afterward they returned to Red River to take five more Indian boys to the school. Pelly soon got sick and died at Red River, but Garry returned to the Spokane country once and for all in 1830. He was about 19 years old.

His years at the Red River clearly set him apart from many of his tribespeople. "Throughout his life, Garry dressed in the costume of the whites, although preferring a blanket to an overcoat for wear in cold weather," wrote his early biographer, William S. Lewis (1876-1941), in The Case of Spokane Garry. "His family also dressed in the costume of the whites, and in the early days lived in considerable comfort, keeping on hand supplies of tea, coffee, sugar and flour, commodities, which some few of the first white settlers in the vicinity did not always possess" (Lewis).

Returning to the Tribe

Yet Garry apparently had no problem remembering his native tongue, because he soon became influential among the Middle and Upper Bands of the Spokane Tribe. He was probably not "the chief" of the tribe in the sense that his father had been -- the chieftainship had passed to a different relative -- but he was undoubtedly an important leader. And because he spoke English and French so well, he soon became the tribe's spokesman in almost all dealings with whites.

He also fulfilled his duty to spread learning through the tribe. He taught them farming methods, which soon gained the Spokane Tribe a reputation for being agriculturally advanced.

He also tried, for a time, to share his academic learning, going so far as to build a rough schoolhouse made of poles and mats near what is now called Drumheller's Spring in Spokane. A visitor to it in 1837 reported that Garry was trying to teach his people to read and write English. These academic lessons were sporadic -- gathering food always took priority -- but he did manage to teach his own offspring how to read and write English. For these reasons, some historians have claimed, with some justification, that Garry was the "first schoolteacher" in the Spokane country (Lewis).

Garry also attempted to be an Anglican missionary to his own people during his early years back from Red River. He had his own Bible and Book of Common Prayer and he would teach lessons from the Bible.

"He told us of a God up above," said Curley Jim, a fellow Spokane. "Showed us a book, the Bible, from which he read to us. He said to us, if we were good, that when we died, we would go up above and see God. After Chief Garry started to teach them, the Spokane Indians woke up" (Lewis).

Consequently his family and many people in his band were well-versed in the Bible even before the first Protestant and Catholic missionaries arrived. However, Garry soon grew tired of attempting to make his mostly unwilling flock adhere to Christian discipline and dropped his preaching. When asked why he abandoned his religious teaching, he said it was because the other Indians "jawed me so much about it" (Simpson).

Still, he remained an avowed Protestant all of his life. Because of the later influence of Jesuit missionaries, the tribe eventually became split along Protestant/Catholic lines.

A Man of Judgment

When Governor Simpson returned to the Spokane country in 1841, he was appalled by a sight that he called a "melancholy exemplification of the influence of civilization on barbarism." A group of Indians were gambling with cards, eagerly thumbing the "black and greasy pasteboard." Spokane Garry was in a nearby tepee, and Simpson blamed him, on scant evidence, for this scene. He claimed that Garry had forsaken his education, "relapsed into his original barbarism" and lost all of his possessions to gambling (Simpson). "He was evidently ashamed of the proceedings, for he would not come out of the tent to shake hands even with an old friend," wrote Simpson (Simpson).

If this is true, Garry reverted right back to solid citizenship. When Territorial Governor Isaac I. Stevens (1818-1862) came through the Spokane country in 1853, he met Garry and wrote in his report that he is a "man of judgment, forecast and great reliability" as well as a man of "education, strict probity and great influence over his tribe" (Lewis).

Another member of the party said that "he is what he claims to be, and what few are among these tribes, a chief" (Gibbs). His tribe, meaning the Middle and Upper bands of the Spokanes, numbered around 500 to 600 people in 1853 and were described as happy and prosperous.

"I Had Two Hearts"

Yet soon Garry and the rest of the tribe would find their relationship with the whites sorely tested. Settlers were slowly beginning to encroach on the region and in 1855, many of the tribes to the south and west of the Spokanes -- including the Yakamas, the Cayuse, Umatillas, and the Walla Wallas -- were in conflict with miners and settlers.

Alarmed, Governor Stevens embarked on a "treaty tour" to encourage tribes to move to reservations. He called a council of tribes in 1855 at Antoine Plante's cabin on the Spokane River. Spokane Garry was there and listened to Governor Stevens's hastily conceived plan to make peace. The Spokane Tribe was predisposed to peace, but they too were alarmed by the encroachments on their land by settlers and soldiers. Garry began his speech to Stevens by making it clear that his emotions were profoundly mixed.

"When I heard of the war, I had two hearts and have had two hearts ever since," Garry said to the assembled council. "The bad heart is a little larger than the good" (Lewis).

Stevens had proposed that the tribe sell its lands and move to a reservation shared with the Nez Perce or Yakama tribes. This proposal showed scant regard for the cultural differences between tribes, and also vastly underestimated the tribes' attachment to their own homelands. Garry made it clear that Stevens's reservation idea was deeply unpopular.

"When you first commenced to speak, you said the Walla Wallas, Cayuses and the Umatillas were to move onto the Nez Perce reservation and the Spokane were to move there also," he told Stevens. "Then I thought you spoke bad. Then I thought you would strike the Indians to the heart" (Lewis).

Stevens, taken aback, said it was only a proposal, not a demand. At the conclusion of the council, Garry, who had emerged as a spokesman for the gathered tribes, issued an eloquent plea for simple respect -- and for simple human understanding.

"When you look at the red men, you think you have more heart, more sense, than these poor Indians," Garry said to Stevens. "I think the difference between us and you Americans is in the clothing; the blood and the body are the same. Do you think that because your mother was white and theirs dark, that you are higher and better? ... I do not think we are poor because we belong to another nation. If you take the Indians for men, treat them so now" (Lewis).

The council ended with Stevens saying that he had merely wanted to "consult" with the Spokanes and Coeur d'Alenes about where they might be moved. He would take their wishes into consideration now that they had "given me their hearts about it" (Ruby and Brown).

Conflicts and Tensions

Yet the situation rapidly deteriorated throughout the region over the next few years. Armed conflict continued on the borders of the Spokane lands, in the Yakima country to the west, and the Nez Perce country to the south. Garry managed to keep the young Spokane warriors out of the conflict, but it wasn't easy. Garry wrote to Stevens in 1856 about the pressures his tribe was under.

"I have heard that the Nez Perces were talking of war," Garry wrote. "That makes me uneasy and study much; for my part I don't like to see them take up their arms, for they will gain nothing by it. I have heard that you talk hard about us, by Indians, but I don't believe it; but I think it is all the Yakimas' doing, to get us to join them, but I don't believe it, for they want me to go to war by all means; but I would rather be quiet."

Garry repeatedly urged that soldiers be kept south of the Snake River, so as not to incite his young warriors. But in 1858, soldiers under the command of Col. E. J. Steptoe (1816-1865) crossed the Snake River and approached the area now known as Rosalia and Steptoe Butte where Garry's tribe and several other tribes were gathering camas roots in the spring. Garry and another chief rode to Steptoe's camp and asked him where he was going and told him that his visit was deeply alarming. Steptoe replied that his was a peaceful expedition to Fort Colville, and that he had no idea it would be seen as a provocation -- even though the expedition was designed as a show of American force. Steptoe decided to withdraw, but before he could, hundreds of warriors from the gathered Yakama, Palouse, and Coeur d'Alene tribes attacked -- and so did some Spokane warriors, despite Garry's apparent efforts to deter them.

Lewis quotes one Spokane man as saying that all the "head men" were trying to hold back the young men and that the "Spokane chiefs succeeded for a time in holding us," but soon the warriors went galloping to the fight (Lewis). Garry himself later wrote, "They would not listen to me, but the boys shot at him; I was very sorry" (Lewis).

Steptoe was forced to make a stand against superior numbers, and was not able to retreat until nightfall. The result: seven soldiers killed, six injured and one missing, while at least nine Indians were killed. Steptoe made it back to safety south of the Snake, but the battle was to have serious repercussions for the tribes and for Spokane Garry. The federal government resolved to crush the troublesome tribes "with a strong hand."

Meanwhile, Garry lost stature in his own tribe, by, first, being unable to prevent an attack in the first place, and second, refusing to join his warriors once it started. "Many a young warrior regarded with scorn the chief who had refused to fight at a time when the youngster thought he was risking his life for his tribe and his lands," wrote biographer Thomas E. Jesset (Jesset).

Anger and Disaster

Garry poured out his anger in a letter to Gov. Stevens and General Newman S. Clarke (d. 1860), the new commander of the region, in a letter in 1858. He said that Stevens had "broke the hearts of all Indians" by suggesting they go to the Nez Perce and Yakima lands. He said it would have been all right if Stevens had just let the Indians decide what portion of their lands to give.

"I am very sorry the war has begun," wrote Garry. "Like the fire in a dry prairie, it will spread all over the country, until now so peaceful. I hear already from different parts rumors of other Indians ready to take in. Make peace and the American soldiers may go about; we don't care. That's my own private opinion."

Yet peace did not come. The Army launched a punitive expedition under Colonel George Wright (1803-1865) in late summer of 1858, which struck deep into the heart of Spokane country. Wright defeated warriors at the Battle of Four Lakes between present-day Spokane and Cheney and a few days later in the Battle of Spokane Plains.

Garry, according to most accounts, did not take part in the fighting -- he had apparently gone to Fort Colville for supplies at the time -- but he felt deeply conflicted about these events. Lewis quotes Garry as telling a white doctor at Fort Colville, "My heart is undecided, I do not know which way to go. My friends are fighting the whites. I do not like to join them, but if I do not they will kill me" (Lewis).

After these two battles, Garry was back with his people on the Spokane River when Colonel Wright's troops moved upstream in search of encampments. In defeat, the tribe once again counted on Garry to try to make peace. Wright held a conference with Garry in what is now the city of Spokane. He ordered Garry to tell his people to lay down their arms, come in to his camp with their women and children and "trust to my mercy." Otherwise, Wright said, "your nation shall be exterminated."

The Killing of the Horses

It's not clear whether Garry conveyed this grim message, and if so, how it was received. A few days later, on September 8, 1858, Colonel Wright rounded up between 800 and 900 horses belonging to the tribes. On September 10, his troops slaughtered nearly every one of them. The rationale behind the decision was expressed by an army board convened to decide what to do with the animals: "Without horses, the Indians are powerless" (Ruby and Brown). The soldiers also burned the Spokane tribe's stores of wheat and other food supplies. Garry, by some accounts, watched somberly from the nearby hills.

With the tribe beaten and devastated, Garry and another prominent Spokane chief, Big Star, met with Colonel Wright a few weeks later, on September 23, 1858, on Latah Creek and signed a peace treaty, which was more like a surrender. The war was over. The next 20 years of Garry's life were spent in a patient and continual effort to secure the only outcome that would preserve the culture and life of the tribe: a substantial reservation on its own ancestral lands.

Survival

Months after the treaty, he wrote to Brigadier General W. S. Harney (1800-1889) requesting a "reservation to be located where we will not be interrupted by the whites, nor our people to have a chance to be interrupted by the whites" (Lewis). Because the city of Spokane would not be founded for another two decades, most of the tribe's traditional lands near the Spokane and Little Spokane rivers would have met these criteria. The land was still mostly unsettled.

Harney forwarded Garry's letter to Army headquarters with the following comment: "In justice to the Indians, this should be adopted by our government; they already cultivate the soil in part for subsistence and, unless protected in their right to do so, they will be forced into a miserable warfare until they are exterminated" (Jesset). The proposal vanished into the bureaucracy.

Garry met with, or wrote, as many officials as he could. General O. O. Howard (1830-1909) said that Garry spoke like a lawyer and "knew how to filibuster like a congressman" (Lewis). Sometimes he was given the brush-off; sometimes he was given promises that never came to fruition. The government threatened again in 1877 to move them to a reservation west of the Columbia. Garry's reply: "What right do you have to dictate to us? This is our country and we will not leave it."

Howard described Garry in unflattering terms: "Spokane Garry was short in stature, dressed in citizen's clothing, and wore his hair cut short for an Indian. He was shriveled, bleary-eyed and repulsive in appearance, but wiry and tough and still able to endure great fatigue, though he must have been at least 70 years of age."

Some of the new white citizens now flocking into the fledgling city of Spokane were far more generous. "I knew him when I was only a boy as he was quite fond of my parents and often stopped at our house for a visit or a smoke with dad," wrote early settler S. T. Woodard. "For years he farmed and raised grain, fruit and vegetables which he sold (and often gave) to his white neighbors. Dad bought seed potatoes of him and a cow in 1884" (Woodard).

"I Will Die First"

In 1881, the government established the Spokane Indian Reservation on the far western edge of the territory, where the Spokane River approaches the Columbia. This reservation was mainly for the Lower Band of the Spokane. Garry's Upper and Middle bands had little interest in joining them. "My tribesmen may go (to the reservation) but as for me, I will die first," said Garry in a speech to a governmental commission (Becher).

In 1887, with the city of Spokane now filling with whites, Garry made one last-ditch request: A reservation on both sides of the Spokane River from the city of Spokane to Tum Tum, about 20 miles downstream. He was turned down.

Instead, the government drew up a treaty for the Upper and Middle bands which relinquished their rights to their land and sent them to the Coeur d'Alene Reservation near Lake Coeur d'Alene in Idaho. Garry, now 76, signed the treaty, as did most of the other head men of the tribe.

Last Years

Yet, Garry, for one, had no intention of leaving. He had his own fine farm nestled at the foot of a hill just east of the present day Hillyard area of Spokane. He retreated back to his farm with his family, only to suffer even more indignity. In 1888, when he went down to the Spokane River to fish for a few days, he returned to find that a white settler had taken his farm. The interloper ordered Garry and his family off.

The old chief had no choice but to leave. He loaded up his possessions and farm equipment, but it took more than one trip to move everything out of the log storehouse he had on the farm. "But when they came back, they found that the white man had burned the cabin, saying that he couldn't wait because he wanted to plow the field," said one of Garry's granddaughters (Becher).

He went to court to get his land back but got no satisfaction. He and his longtime wife, Nina, now blind, his family and a few followers, set up their tepees on Latah Creek, just outside of town, beneath today's Sunset Highway bridge. Young boys thought it was great sport to throw rocks from a bridge onto the old Indian's tepees. Now, when he went to town, he seemed to stare "coldly" at the white passersby (Finney).

Harassed, he and his small band moved to Indian Canyon, just west of Spokane, where a white landowner allowed him to camp. It was there that he died on January 12, 1892, after a long decline. He was probably about 81. His estate consisted mostly of his Bibles and other religious books -- some of which dated from his Red River days -- and a few Cayuse ponies. The books stayed in the family and are now housed in the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture. Most of the ponies were stolen before the estate could be settled. He was buried at Greenwood Cemetery in a pauper's grave with a small wooden cross.

Honoring Chief Spokane Garry

The Review, a Spokane newspaper, eulogized him in a lengthy editorial. "Garry insisted upon having a reservation of his own and this he was never able to secure," said The Review. "Death had made terrible inroads into the tribe and as of late his chieftainship has been only nominal. His people are either dead or scattered ... Alas, poor Garry! The story of his life, interwoven with that of the death of his people, might well be made a theme of poetry, to endure long after the last Spokane has vanished from the land" ("The Life of Garry").

Yet the Spokanes did not vanish, and Garry certainly was not forgotten. In 1925, the Spokane Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution erected a large granite monument over his grave. In 1932, a Spokane city park, not far from where he used to run horses, was named Chief Garry Park. A Spokane school was named Garry Middle School.

A fine concrete statue of Garry was erected in Chief Garry Park in 1979. Over the years, the statue began to crumble from the elements. Vandals broke off the statue's fingers. In 2008, it was ordered removed from the park. In the process, it was reduced to a pile of rubble.

The City of Spokane announced it would replace the statue with an abstract "totem" sculpture. However, a grass-roots drive sprang up almost immediately to fund a more appropriate replacement memorial to Chief Garry. In 2011, a new $40,000 circular stone monument was dedicated at the park, complete with a replica of an ancient pictograph, a steel salmon, and interpretive signs about Garry's life. Spokane Garry's face once again looks out over his old homeland.