Seattle's Kearney Barton was the man whose audio engineering work can be credited with forging the powerful aural esthetic that became widely known as the "original Northwest Sound." While numerous musicians also contributed to the process, it was Barton who established what that "Sound" sounded like on classic records by pioneering area rock 'n' roll bands including the Frantics ("Werewolf"), Playboys ("Party Ice"), Little Bill ("Louie Louie"), the Kingsmen ("Jolly Green Giant"), the Counts ("Turn On Song"), the Sonics ("Psycho"), and Don and the Goodtimes ("Little Sally Tease"). But Barton's half-century of activity also saw him produce recordings for a wide range of clients including the Seattle and Portland opera companies, jazz/pop icon Quincy Jones, Scandinavian humorist Stan Boreson, country/pop diva Bonnie Guitar, the SuperSonics and Sounders sports teams -- and even the performance soundtracks for Washington's 1984 Summer Olympics Gold Medalist swimmers, Traci Ruiz and Candy Costie. Perhaps most significantly though, through instructional classes held at his Audio Recording studios over the decades, Barton trained and mentored an entire generation of students in the arts and sciences of audio engineering. Kearney Barton died on January 17, 2012.

Professor Barton's Fine Music

Born in Oregon -- Oregon, Missouri, that is -- Kearney Barton's family moved out to Washington in 1945 when he was age 17. Initially settled into one Central Area home (712 23rd Avenue), Barton began attending Garfield High School that fall, but after a couple months the family moved (2710 27th Place S) and he transferred to Franklin High where he enjoyed roles in various theatrical productions. Entering the University of Washington's School of Drama in the fall of 1949, Barton lasted only two quarters before taking on a job grinding aromatic spices for Seattle's Crescent Manufacturing Company -- a task that resulted eventually in an allergic reaction, and got him casting about for a different opportunity.

Around 1951 Barton took on a part-time gig as a technician and radio DJ -- Professor Barton's Album of Fine Music show -- at the tiny 1,000-watt station KTW, which was owned by, and operated out of, Seattle's First Presbyterian Church (1013 8th Avenue). "I was working at KTW," recalled Barton, "running the transmitter and doing the on-air work at the same time -- in those days you ran a tape, spun the records, and everything else. I did some recording for them of on-location programs of choirs and orchestral things and so forth" (Blecha interview, 1983).

Those were the days when Seattle could boast of a mere three or so active recording studios, and it just so happened that KTW's Program Manager, Don Bevilacqua, also fulfilled that role at station KNBX, which was then airing its Christian Businessman's program from a studio located on the mezzanine level in the back of Oliver Runchey's downtown hi-fi supply/fix-it shop, Electricraft, Inc. (622 Union Street). The Electricraft studio had previously been the home of early sessions by area talents that included "Texas Jim" Lewis, Norm Hoagy, and "Morrie" Morrison's band. But then, in the fall of 1957, KNBX lost its engineer, Billy Watson Jr., who left to work for Boeing. Bevilacqua suggested that Electricraft hire Barton as a replacement. Runchey had, however, grown disinterested in his studio, and thus failed to offer a reasonable wage. In response KNBX bought the place and hired Barton in February 1958.

Northwest Recorders

Wanting to differentiate the new enterprise from the Electricraft operation, KNBX accepted Barton's suggestion to rename it Northwest Recorders. By that summer of 1958, KNBX lost its religious broadcast contract to another station and then suddenly wanted to bail out, creating an opportunity for Barton to take over the gear and lease the Northwest Recorders studio as his own operation. This timing was perfect in that the founders of Dolton Records -- record salesman Bob Reisdorff, and pop star Bonnie Guitar -- were scouting out possible studios they might use for future projects.

"When I started there I had never run a studio you know, and I had to teach myself to do the actual recording and disc-cutting and so forth. Well, right after getting into it -- actually, I was just setting up -- and Bonnie Guitar and Bob Reisdorff came in to do a demo with somebody and they liked the sound that I got 'em. Then Bonnie liked the sound I got on her voice. And then they tried the Fleetwoods. You know, Bob and Bonnie kinda taught me recording as it were: you know, what they were looking for. I mean, I was teaching myself how to record these groups -- but I'd really never done that much. My first real exposure to rock 'n' roll was when I got in the recording business cause I'd been working in a radio station doing [laughter] classical" (Blecha interview, 1983).

Dolton Days

Bob Reisdorff partnered with Bonnie Guitar in the latter part of 1958, forming the new Dolton Records company, which scored an international smash hit in early 1959 with its debut release, "Come Softly To Me," by the Olympia-based doo-wop teen trio, the Fleetwoods. That session, however, actually took place across town at Joe Boles's Custom Recorders in West Seattle -- as did the label's next couple hits as recorded by their next assignees, the Seattle combo the Frantics, and Tacoma's rockin' ringleaders, Little Bill and the Bluenotes.

But after a falling out with Boles, Dolton switched over to Barton and their first collaboration led to the Fleetwoods' second smash, the national No. 1 hit, "Mr. Blue," in September 1959. Meanwhile, Electricraft had moved out to a new site around the corner (1408 6th Avenue), and Dolton wisely slipped right into the hi-fi shop's former space. Now the new label was situated in a very convenient proximity to Barton's operation where the lion's share of its subsequent sessions would take place -- including those with the Frantics, Four Pearls, Playboys, and tracks for the Ventures' debut LP in 1960.

Inspired by Dolton's remarkable string of successes, loads of area entrepreneurs formed their own labels, and many of those folks marched down to Northwest Recorders to try their luck at the pop music crapshoot. Among the first to book studio time was Everett's doo-wop group, the Shades, who brought along a freelancing engineer, Glenn White Jr., who produced a couple tunes --"Dear Lori" and "One Touch of Heaven" -- that were ultimately issued by the fabled Los Angeles R&B label, Aladdin Records. Amped up by their surprise success, two of the Shades -- Larry Nelson and Chuck Markulis -- proceeded to form their own Nite Owl Records and a session with Seattle's doo-wop crew, the Gallahads, produced that label's classic, "Gone," which helped get them signed to Hollywood's Donna Records around September 1959.

Barton was soon busy twisting the knobs for countless other early rockgroups, including Spokane's Blue Jeans, Seattle's Appeals (whose "Thunderbolt" failed to win them a hoped-for Dolton contract), and the Viceroys ("Blue Ivory"), Bellingham's Swags (whose instrumental, "Blowing The Blues," saw release on Hollywood's Del-Fi Records) -- and even, according to Barton, an early (as-yet-unreleased) session with one of young Jimmy ("Jimi") Hendrix's teenaged combos.

The Lost "Louie Louie"

One of the new Seattle record companies was John Hill and Rick Wheeldon's Topaz Records, which booked a session around March 1961 for former Dolton hit-maker, Little Bill Engelhart, who was now singing with the Adventurers. Unfortunately, it was while cutting a promising version of the region's fave dance tune -- Richard Berry's "Louie Louie" -- that Engelhart's old musician pal, Wailers' bassist Buck Ormsby, stopped by to visit and saw what Topaz was up to.

Concerned that his own band's recent (although unreleased) recording of the tune was about to get trumped, Ormsby scrambled to race a copy of the Wailers' version over to KJR radio, which quickly pumped it up to No. 1 regional hit status. That made the Adventurers' eventual release a moot point, albeit a very cool rarity in hindsight.

Audio Recording, Inc.

Such interactions with Topaz did, however, have positive repercussions for Barton when a few years later the label was in such financial arrears to the studio that he wound up accepting ownership of the label in recompense. And as business activity increased, he had reason to also launch a couple more labels, Kay-Bee Records, and Audio Records -- which was founded after Barton moved over to 170 Denny Way in September 1961 to start fresh as Audio Recording, Inc. Around that time many opportunistic businessmen were gearing up for the coming 1962 Seattle World's Fair by producing tourists trinkets of every type, and Barton soon found himself cutting a number of boosterish 45s including the Misfits' "Come On World To The Fair," and the Frank Sugia Trio's "I'm Going To Seattle (To the Great World's Fair)."

Back then -- and to the end -- Barton welcomed a wide range of musicians into his studios, which were the site of pop sessions with Seattle’s Pat Suzuki (“Bow Down To Washington”) and San Francisco’s Cables; folk sessions with the Brothers Four (“My Tani”), the Town Criers, Bacchus Trio, Upper U District Singers, and Danny O’Keefe; R&B sessions with Merceedees, Ron Holden, Curtis Ware, Little Daddy and the Bachelors, Frank Roberts and the Soul Brothers, and the Checkmates (who scored much later with the 1969 hit, “Black Pearl”); a Quincy Jones-led blues session with Guitar Shorty; a session with the Northwest’s earliest known bluegrass band, Fred McFalls and his Carolina Mt. Boys, and later the Hurricane Ridgerunners; gospel sessions with the Singing Gallatians and the Seattle Baptist Choir; Dixieland jazz with the Dirty Beaver Jug Band; funk sessions with Black on White Affair and the Soul Swingers; sessions with jazz luminaries such as Dave Brubeck, Ray Brown, Cal Tjader, Les McCann, Earl Grant, and Paul Bley; country sessions for big-time artists including Little Jimmy Dickens and Don Williams; and many ethnic-oriented bands including Mariachi Mexicali, Caribbean Allstars, and the Seattle Balalaika Orchestra. But, despite this vast musical diversity, it remains the realm of rock ‘n’ roll that is Barton’s real claim to fame.

Garage Rock Echoes

Between 1963 and 1964 Barton stayed busy cutting discs for talents including the Dave Lewis Trio, Imperials, Checkers, Beachcombers, Accents, Billy Saint, Ian Whitcomb, and countless others. Then in April 1965, Barton expanded Audio Recording by moving to a much larger facility in a former muffler repair shop. It was at that site (2227 5th Avenue) that Barton hired Glenn White Jr. (who was the audio engineer for the Seattle Center) to design three (soon-to-be-legendary) live echo chambers -- one of which was built into an old spray-painting booth. In addition, Barton upgraded by acquiring the town's first three-channel stereo tape recorder, and taking on two new partners: Bob Flick (a member of the Brothers Four) and Jerry Dennon (the founder of Jerden Records, also soon based within the 5th Avenue facility).

Jerden Records had launched the Kingsmen's 1963-1964 hit, "Louie Louie" -- which had been recorded in Portland in April 1963. Then -- late in the year when the tune became a sudden national hit -- Barton set his gear up at that town's teen-club, The Chase, and recorded the band's debut LP. The Kingsmen went on to cut a string of hits at Audio, as would scores of tuff Northwest garage combos including Don and the Goodtimes, the Wailers, Sonics, Bootmen, Elegants, El Caminos, Raymarks, Counts, Dynamics, Dimensions, Galaxies, Hustlers, Eccentrics, Artesians, Extremes, Bandits, Castells, Express, Ceptors, Page Boys, Legends, Incredible Kings, Nomads, Vandals, Jet City Five, Mercy Boys, City Limits, Plymouth Rockers, Liberty Party, Misterians, Thee Unusuals, Merrilee Rush and the Turnabouts, Sir Raleigh and the Cupons, Tom Thumb and the Casuals, Jack Horner and the Plums, Mr. Clean and the Cleansers, George Washington and the Cherrybombs, and Rocky and the Riddlers. Then -- after word spread that Audio was the place to capture the perfect garage-band sound -- even outsider bands began to flock to Seattle to record including the Canadian VIPs, New Jersey's Knickerbockers, and California's Standells.

Changing Times and Sounds

As the times changed so did rock 'n' roll, and by 1966 Barton was recording the new breed of folk-rock and early hippie bands including, the Brave New World, Daily Flash, Emergency Exit, Magic Fern, PH Phactor Jug Band, Springfield Rifle, Bards, Bumps, and Bluebird. Barton did a couple of particularly portentous sessions with a folkie band called the Daybreaks whose two Topaz 45s -- "Through Eyes and Glass" and "Standin' Watchin' You" -- featured the lead vocals of future superstar (with the band, Heart), Ann Wilson.

But as the 1960s flowed into the 1970s, the Northwest music scene lost considerable momentum: Certain area radio stations were sold off and no longer supported local discs, and nearly all of the successful local labels folded. Simultaneously, several new studios (mainly founded by former musicians) arose to compete over the shrinking pie. Also, Seattle's first well-financed facility, Kaye-Smith Studios (2212 4th Avenue) was launched and its presence seriously affected the commercial scene -- although, its high hourly rates basically precluded all regional local bands except the few with big-time corporate backing (e.g. Bachman Turner Overdrive and Heart) -- from utilizing the place.

Barton and Audio Recording, however, picked up the slack during those lean years by offering sound engineering classes to the public. And in time -- when the punk rock movement began stirring in the 1970s and a new-found appreciation for the old '60s garage esthetic emerged -- snotty Seattle bands like the Lewd and the Girls (and even that post-punk Power Pop crew, the Young Fresh Fellows, and veteran bluesman, Jack Cook) purposefully recorded with Barton at Audio in order to gain his trademarked magic ultra-lo-fi sound.

Barton's "Flawless Secret Recipe"

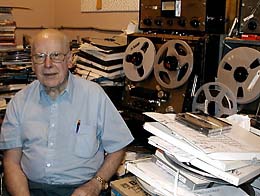

In October 1981, Barton made one last move, relocating Audio to a large studio (4718 38th Avenue NE) based within his home bordering North Seattle's Bryant and Laurelhurst neighborhoods. At this writing (2008), he was still teaching and accepting bookings, although he was beginning to scale back his work schedule. Admiration for his historic work from the 1960s seems only to grow as the years pass by.

In 2001 New York's garage-rock-crazy Norton Records company even licensed enough previously unreleased vintage material from Barton's vault to issue a three-volume set of Northwest Killers compact discs. In their typically over-the-top liner notes to Volume 3 in that series, label heads Billy Miller and Miriam Linna paid tribute to "Professor" Barton's contributions to those vintage sounds with this sincere salute: "Kearney Barton ... concocted his own flawless secret recipe at his first studio, a stupefyingly splendid prescription that simply cannot be duplicated, not even with all the computers and big-head record moguls in the world daisy-chained and plugged into an overamped supercollider semiconductor, wet." Hear, here!

Kearney Barton died on January 17, 2012.