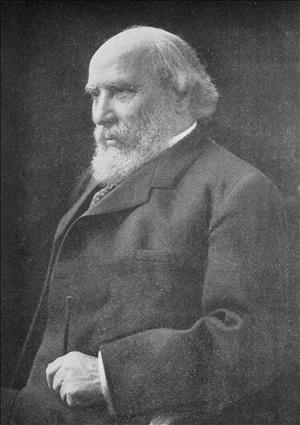

On November 5, 1908, a train bearing James J. Hill (1838-1916), chairman of the Great Northern Railway, and several business associates and dignitaries leaves Spokane, crosses the Columbia River from Pasco to Kennewick on a bridge owned by the Northern Pacific (also controlled by Hill), then travels along the north bank of the Columbia River to Vancouver on the tracks of the recently completed Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway (SP&S). From there the train moves on to Portland, crossing the Columbia on the first railroad bridge to link Washington and Oregon. The following evening a gala banquet in Portland will celebrate the completion of the new line, commonly called the North Bank Road. The SP&S is jointly owned by the Northern Pacific and Great Northern railroads. Built at a cost well in excess of $40 million, the new line provides an alternative to the punishing rail routes over the Cascade Mountains and frees the Northern Pacific from its earlier reliance on Oregon tracks owned by Hill's chief rival, E. H. Harriman (1848-1909).

Hill, Harriman, and Elliott

James J. Hill's train ride across the Columbia River that November day signaled a major victory in his long and bitter competition with E. H. Harriman for railroad dominance in the Northwest. Hill, known as the "Empire Builder," had completed the Great Northern Railway (GN) into Seattle in 1893, coming down from the north after crossing the Cascades at Stevens Pass. In 1901 he won indisputable control of the Northern Pacific Railway (NP) after a stock-purchase battle with Harriman that almost brought down the New York Stock Exchange. The NP line reached Tacoma and Seattle from the east over Stampede Pass, and with these two transcontinental lines Hill had a near monopoly over long-distance rail access to the rapidly growing cities on Puget Sound. Harriman's interests were concentrated farther south. He had purchased the Union Pacific in 1897 and the Southern Pacific in 1901, and these lines gave him dominance both in Oregon and on the valuable routes that served California.

These were ambitious men, and each had something the other wanted. Hill's Northern Pacific trains originating in Spokane had only a tortuous route to Oregon that was punishing, long, and required two crossings of the Columbia River. The first linked Pasco and Kennewick on a span the NP had completed in June 1888, the first permanent railroad bridge to cross the mighty river (the NP had opened a temporary bridge there in December 1887). From Kennewick, NP trains traveled west, crossing the Cascade Mountains at Stampede Pass to reach Tacoma and Seattle. To access Portland, then the largest city in the Northwest, NP trains had to travel south from the Puget Sound cities to Kalama on the Washington side of the Columbia, from where they were barged across the river to Goble, Oregon. At that point, their only access to Portland was on the eastbound tracks of the Harriman-owned Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company. What Hill wanted was direct access to Vancouver and Portland and to get rid of both the train barges at Kalama and the need to use tracks from Goble to Portland that were controlled by his primary competitor.

For his part, Harriman wanted rail access to Washington. He had been unable to penetrate the rapidly growing Puget Sound country, where Hill's Great Northern and Northern Pacific held sway. Harriman offered to trade the continued use of his Oregon tracks by the NP in exchange for use by the Union Pacific of Hill's line that ran north to Puget Sound, an offer that did not fit with Hill's ambitions and was brushed aside.

A Very Open Secret

One of the peculiarities of the complicated railroad battles of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was that separate lines that were controlled by the same men often directly competed against one another, and with considerable vigor. Although the Northern Pacific was controlled by Hill through stock ownership, it was run with a great deal of independence by a veteran railroad executive, Howard Elliott (1860-1928). It appears to have been Elliott who first developed the plan for a new railroad that would link the NP's existing facilities in Spokane directly with Portland. The proposed route would travel much of the way along the north bank of the Columbia to Vancouver in Clark County. From there, two bridges would carry trains across the Columbia and a third across the Willamette River to reach the railroad yards of Portland.

There were reports as early as 1903 that someone was quietly buying up rights-of-way along the north bank of the Columbia River, and by early 1905 these efforts had become too obvious to ignore. Attempts at secrecy were not helped by the fact that surveyors were using tools clearly marked as belonging to the Northern Pacific and cashing paychecks issued by that company. Nonetheless, it was not until September 1905 that the Portland & Seattle Railway Company was incorporated. Although the railroad's initial name did not include the word "Spokane" and none of its original incorporators had clear ties to Hill or the Northern Pacific, it was now obvious that the NP's primary goal was not to link Seattle and Portland, as the name implied, but rather to link Spokane and Portland with a new railroad that would in large part follow north bank of the Columbia. As Elliott later put it, "Someday some road would have it. We wanted to be that road" (Pease, 2-3).

Hill Builds, Harriman Hesitates

In October 1905 James J. Hill dropped the other shoe, announcing at Portland's Lewis & Clark Centennial Exposition that his Great Northern would join in the development of the new railroad as an equal partner with the Northern Pacific. Hill rather coyly explained, "I suppose the Northern Pacific would be jealous of the Great Northern building there, and we would be jealous of their building there, so we concluded that we would build jointly ... ." (Pease, 4). Asked why the chosen route went through the difficult Columbia Gorge, where hard, basalt cliffs shouldered right to the water's edge, Hill answered, "Nature made the pass. Water follows the line of least resistance, and so does commerce" (Pease, 5). He was referring to the fact that the gorge was the only place in the entire state of Washington that offered a way across the Cascades without significant changes in elevation. All other rail routes through the mountains required switchbacks and steep climbs and descents that were hard on equipment, were wasteful of fuel, and limited maximum loads. In contrast, said The Seattle Times, the new road was "to all intents as level as a table and as straight as a string" ("North Bank Line Is Formally Opened").

The normally astute Harriman seemed for once to have been, in railroad terminology, asleep at the switch, and he waited too long to challenge the Hill forces. When he finally stirred to action, he sent large crews of lawyers to court and small crews of workmen, armed with little more than picks and shovels, to various points along the planned route where the Hill forces had not yet secured full rights-of-way. Harriman's legal efforts failed, and his construction activity was so desultory that in 1907 a court ruled that he in fact had no real plans, was merely trying to harass his competitors and slow their progress, and should be legally barred from further interference.

With Harriman's challenge now beaten back, work proceeded without cease. No longer needing subterfuge and facing pressure from the citizens of Spokane, Hill announced in early 1908 that the entity incorporated as the Portland & Seattle Railway would in fact be called the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway, reflecting its true route and larger ambitions.

Building the Road

As noted above, the NP already had tracks, laid in the 1880s, that ran from Spokane to Pasco, crossed the Columbia by bridge to Kennewick, then ran northeast and over the Cascades to Tacoma and Seattle. The new railroad, although owned in its entirety by the NP and GN, was a separate legal entity, and its managers decided in early 1906 to build a better set of tracks between Spokane and Pasco as part of the new route. This work would be saved for the last, however, and the main effort between late 1905 and 1908 was to lay tracks from Kennewick to Vancouver and there build the bridges that would carry the trains on to Portland.

It would be neither easy nor cheap. Thirteen tunnels and nearly 30 bridges and trestles were required along the 220-mile section between Kennewick and Vancouver. The original estimates of cost were in the range of $8 million; in the end, it totaled well more than $40 million, an outlay that reportedly had Hill privately expressing regret for having ever started the project. But when completed, the SP&S accomplished several things. It provided the first rail access by bridge between Washington and Oregon. Its tracks passed through nearly 80 villages and towns, providing a source of business for the railroad while also connecting long-isolated communities to the wider world. It allowed the two Hill lines, the Northern Pacific coming from the east and the Great Northern coming from Puget Sound country, to meet up at Vancouver, from whence both would eventually share the bridges of the SP&S to reach Portland. Finally, by providing a route to Portland that didn't rely on Harriman's OR&N tracks on the Columbia's south bank, the project brought Hill closer to his long-term goal of running his own railroads all the way to California (an accomplishment that came only some years after his death).

The Washington portion of the SP&S was completed by January 1908 and two months later, on March 11, 1908, the new railroad held its Golden Spike ceremony at Sheridan's Point in Skamania County (just upstream from the future location of Bonneville Dam). A 10-coach train left Vancouver that morning for the event, carrying nearly 400 celebrants. Regular passenger traffic between Vancouver and Pasco/Kennewick began later than month, and trains could continue on from Pasco to Spokane (at first along using the Northern Pacific's existing tracks). However, spanning the Columbia from Vancouver into Portland to complete the road was to take a little longer.

Crossing the Columbia

As it flows between Vancouver and Portland the Columbia River is bifurcated by the long and narrow Hayden Island (called Shaw Island in years past). The river fork that flows on the north side of the island was called on some maps the Washington Channel, while that on the south side was referred to as the Oregon Slough. Each fork of the river would need a separate bridge, and each would require a swing-span to allow water-borne commerce to pass. The two spans would be connected by a plate-girder viaduct that carried trains across the island. A third draw span would be needed to cross the Willamette River to the south.

To design the bridges, the SP&S hired the best in the business, Ralph Modjeski (1861-1940), a Polish-born civil engineer who had immigrated to America in the 1880s. It was decided that although the railroad was a single-track line between Spokane and Vancouver, the bridges should carry two separate tracks, allowing simultaneous traffic into and out of Oregon. Because the Columbia River was a navigable waterway under federal jurisdiction, the U.S. War Department had to approve the construction, which it did on February 14, 1906.

The 2,806-foot-long steel-truss bridge to be built across the north fork of the Columbia (the Washington Channel) was touted as the longest double-track railroad bridge in the United States. Its 446-foot swing-span would pivot on a concrete pier that, ironically, Harriman had built several years earlier during an abortive attempt to extend his rail empire into Western Washington.

The bridge across the Oregon Slough, of similar design, would be shorter, at 1,466 feet, and the Willamette River crossing was 1,762 feet in length. The latter had its own claim to fame: the bridge's swing-span, at 521 feet, was deemed at the time to be the longest of its type in the entire world. (In 1989 the Willamette swing-span was replaced by a vertical-lift section, while the two northern bridges have retained the original pivot design.)

Work on the bridges began immediately after the War Department's approval, and with the exception of the draw-span machinery they were completed by late July of 1908. Putting the finishing touches on the Columbia and Willamette river crossings took until the fall of that year. Although at least one work train had used the spans during late-stage construction, the ceremonial passage on November 5, 1908, that carried Hill and his cohorts to Portland marked the first time a passenger train had crossed between Washington and Oregon by bridge.

The Celebration

James J. Hill and several of his party arrived in Spokane by train from the East. On November 4, 1908, a morning train trip to the large lumber mill in Potlatch, Idaho, was followed by a luncheon at Spokane's Hall of the Doges. In a lengthy speech, published verbatim in the next day's Spokesman-Review, Hill stressed the interdependence of the city and the SP&S:

"Bear this in mind, the railroads can only prosper with your prosperity, and if you are not prosperous, depend upon it, your railroads will be poor ... . It is [in] our own selfish interests to help you to grow, and we always expect to hold that position toward you" ("Hill Foretells Greater Spokane").

On November 5, Hill and his party boarded the special train for the celebratory run west. They traveled in comfort and safety to Vancouver, and as they crossed the Columbia to Portland Hill stood on the train's rear platform, looking up and down the river. According to a newspaper account, a friend asked Hill, "How do you like it?" and he answered "Great." He was then asked if he considered the completion of the new railroad "the crowning achievement of your life." He laughed and responded, "I am still young -- as young as I was 30 years ago" ("Hill Inspects His North Bank Road").

Among those accompanying Hill on the celebratory run were his son Louis W. Hill (1872-1948), who was president of the Great Northern; Howard Elliott, president of the Northern Pacific; George B. Harris (d. 1918), president of another Hill-controlled line, the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy; H. C. Nutt, general manager of the Northern Pacific; A. M. Gruber, general manager of the Great Northern; and, prominently, Francis B. Clarke (1839-?), the president of the new SP&S. Hill's longtime rival, E. H. Harriman, was not in evidence.

After arriving at Portland, the train was switched onto tracks owned by the Astoria & Columbia River Railroad, another joint enterprise of the NP and GN. The party traveled on that line to Astoria near the mouth of the Columbia for what was billed as an inspection tour, and apparently stayed the night. They returned to Portland on November 6 for a banquet sponsored by the city's Commercial Club, reputed to be the largest such commercial celebration the city had ever seen. More than 350 were in attendance, including many regional business leaders, along with Oregon Governor George Earle Chamberlain (1854-1928) and his Washington counterpart, Albert Edward Mead (1861-1913).

Inevitably, there were speeches galore, including by the two governors, and by Hill the elder, Elliott, Clarke, and at least seven other dignitaries. Hill was circumspect in his remarks about future plans; statements he made years earlier about the development of the SP&S had led property owners along its route to demand high prices for rights-of-way across their land. Hill was not one to make the same mistake twice, and generally addressed the assembled with commercial platitudes. He did, however, express some farsighted views about natural resources and population growth:

"Let us educate ourselves to take care of our resources ... We have, in the past, been reckless. Formerly, we could abandon the old field and move on to a new one, but the tide of immigration has already reached the Pacific Ocean ... and people will come to the United States from other countries as long as we pay the highest scale of wages in the known world" (Pease, 11).

The Morning Oregonian waxed ecstatic and, given future developments, excessively so:

"The opening of this railroad means the commercial supremacy of Portland in the Pacific Northwest. In addition to connecting the city directly with two transcontinental railroad systems — the Great Northern and the Northern Pacific — Portland is made the natural gateway and metropolis of a water-grade route from the wonderfully productive Inland Empire to the sea" ("Portland Greets Empire Builder").

Certainly the SP&S proved of great benefit to Portland, and it remains today a vibrant port city. But after their visit there, Hill and several members of his party traveled on his train north to Seattle and on to Vancouver, British Columbia. In later years, both those cities would surpass Portland as commercial and shipping centers, due in significant part to Hill's Great Northern and Northern Pacific lines.