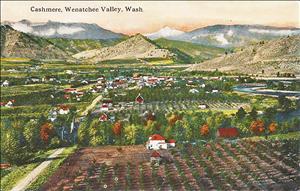

The town of Cashmere in Chelan County is among the most picturesque in Washington. It lies on the southern bank of the Wenatchee River about midway between its turbulent upper reaches at Leavenworth and its more placid confluence with the Columbia at Wenatchee. The 8,500-foot Mount Cashmere and neighboring peaks of the Cascades are clearly visible to the west. The narrow benches of land surrounding the town are covered with fruit orchards. Catholic missionaries established several missions among the Wenatchi Indians along what was soon named Mission Creek, which flows into the Wenatchee at Cashmere. Early non-Indian settlers who followed called their tiny village Mission, or Old Mission. Growth was assured with the coming of the Great Northern Railway in 1892 and the town was platted that year. A post office was established in 1889. In 1904 the name was changed to Cashmere and the town was incorporated. The introduction of irrigation in much of the Wenatchee Valley greatly enhanced agriculture, particularly the growing of apples and other fruit, for which Cashmere has become renowned. Today Cashmere thrives on a combination of fruit production, tourism, and a small industry for which it is famous, the candymakers Aplets & Cotlets.

Early Years

Ntuatckam, a Sinpesquensi village of about 400 in 1850, stood on the site of present Cashmere. The Sinpesquensi (or Sinkaensi or Sinpeskuensi) were a band of the Wenatchi Indians, who found a bountiful supply of food in the salmon, camas roots, berries, and game animals of the region. During the period before the major influx of non-Indian settlers, Catholic missionaries, particularly Father Urban Grassi, had worked to convert the Indians of the area. Over the years, they built several small missions, the main one being St. Francis Xavier, constructed in 1873. In 1888 they erected the church building that gave the new settlement, which later became Cashmere, its first name: Mission, or Old Mission.

During its first years, the main resources around Mission were timber and sheep ranching, and the town soon became a trading center. In 1881, the first non-Indian settler, German immigrant Alexander Brender (1851-?), established his homestead in Brender Canyon. In 1882, D. S. Farrar arrived. He raised hay and is credited with bringing the first fruit trees in 1883. Other settlers came, including William Bourgwardt, Matt Green, Denis Strong, O. C. McManus, and Reuben A. Brown.

Most of these early settlers and the goods to supply the community arrived in Cashmere by way of nearly impassable roads and trails from Ellensburg over Blewett Pass, treacherous even well into the automobile era. Others came by steamboat on the Columbia and by trails along the Wenatchee. There were no bridges across the Wenatchee, which had to be forded in several places.

Roads and Rails

Today three bridges span the Wenatchee at Cashmere. When the original Sunset Highway opened in 1915 connecting Seattle with Spokane by way of Snoqualmie and Blewett passes, it went directly through Cashmere's residential district and downtown. In the 1940s the route of Sunset Highway (U.S. 10) was shifted southward to run through Ellensburg and Vantage, and the highway through Cashmere became part of U.S. 2. In 1959 a four-lane bypass was opened between Cashmere and Dryden, part of the improved Highway 2 over Stevens Pass. On October 19, Governor Albert D. Rosellini (1910-2011) cut the ribbon at the opening ceremony. Apparently the town had no objections to this bypass of its commercial center, for according to the Wenatchee World of October 19, 1959, "The new highway stands as a tribute to Mayor Eric Braun and all the citizens of Cashmere and Dryden whose effort made this highway possible" (Ingraham, 69).

A post office was established in 1889 with John Frank Woodring as postmaster. On July 27, 1892, John F. Woodring and I. W. Sherman registered a plat for a new town site. The Great Northern Railway arrived in the Wenatchee Valley during the same year.

The first decades of the twentieth century saw great civic improvement. In 1904 Mission acquired its first physician, Dr. Harry J. Martin. Elms and poplars were planted along the streets, and before 1910, telephones had arrived. The town had paved sidewalks by 1913, electric lights in 1914 and paved streets in 1919. The Cashmere Valley Record has been in continuous publication since 1907.

The Coast magazine of October 1906, describes Cashmere, which had shipped 135 carloads of fruit the previous season, as:

“one of the prettiest and most prosperous horticultural districts in the state. The city has a population of about 450 with 1,600 people living in the valley in the immediate vicinity. Here we see the first evidences of the wonderful outcome of irrigation. Thrifty and productive orchards grow in all directions in the midst of which are large, comfortable and attractive homes” (Coast, 195).

Beginning in about 1905, the Cashmere Hotel, later named the Blewett Hotel, was “the social center of the valley” and “the gateway to Blewett Pass” (Ingraham, 18, 19). During the 1960s, it was converted to apartments and later razed.

From "Mission" to "Cashmere"

Perhaps the biggest change during the early years was the new name. Mission shared its name with several other towns in the Northwest, causing problems for mail and train service. Judge James Harvey Chase (1831-1928) suggested the name Cashmere from a popular and sentimental poem, “Lalla Rookh,” by Sir Thomas Moore, extolling the mountainous beauty of the Vale of Kashmir in Himalayan India. The judge had once been a teacher of elocution, famed for his public readings, and no doubt this poem was part of his repertoire.

The new name was officially adopted on July 1, 1904, and that November the community incorporated under the new name as a city of the fourth class. James Chase was a community activist instrumental in the creation of Chelan County and secretary treasurer of the Peshastin Ditch, an important element in the irrigation system. In his old age, the locals referred to him as "Cashmere's grand old man." In April 1911, the popular judge gave a "most entertaining and instructive" talk for the Cashmere Woman’s Club recounting the name change (Brooks, 348).

Water and Apples

Cashmere thrived with its new name, the advent of the railroad, and the expansion of irrigation. By 1910 its population had grown to 625 and by 1920 to 1,114. Efforts to irrigate the valley around Cashmere started in about 1889 when a group of pioneers laboriously began digging the Peshastin Ditch, which first delivered water in 1901 to the orchard land on slopes above Cashmere. This ditch eventually became part of the complex Wenatchee Valley system that included the Shotwell Ditch and the much larger Highline Canal. Together they water orchards from Dryden down to Wenatchee.

With all these apples being produced, boxes were needed for shipping. Frederick Schmitten (d. 1939) opened a mill and box factory in Brender Canyon in 1902. He also employed loggers in five locations in the woods. In 1910 he built a general lumber mill in Cashmere, providing employment for many years for mill workers and loggers. In 1973, this company was purchased by Pack River, which continued operations until 1977.

Clubs, Churches, Libraries, Schools

Cashmere seems never to have been a typical “wild west” town, even during the Mission days. Although it had its share of saloons patronized by miners from the Blewett Pass gold fields, such refinements as churches, lodges, and a woman’s club were more indicative of the town’s character. In 1905 a group of women began meeting socially and on January 17, 1906, formally organized the Minerva Club (for the Roman goddess of wisdom and the arts), later called the Library Club. It founded a reading room that became the nucleus of the public library. In 1910 it joined the Washington Federation of Women’s Clubs and in 1913 became the Cashmere Women’s Club. The Grange, American Legion, and later, Rotary and Lions clubs, and Boy Scouts (its troop formed in 1910 and was one of the first troops in the West), were among the many organizations in Cashmere.

The first church, other than the early missions, was the Presbyterian Church, with its first building erected in 1893. It was the first home of the Cashmere School and the library that succeeded the Minerva Club reading room. The present library has been part of the North Central Library System since 1959. Through Grange and Chamber of Commerce efforts, Cashmere has been home to the Chelan County Fair since 1953.

From its earliest days, Cashmere has been proud of its good school system. The first one-room schoolhouse in the Cashmere Valley was built in the 1889 at the mouth of Brender Canyon and now is part of the Cashmere Museum’s Pioneer Village. The earliest classes in Cashmere were held in the old Presbyterian Church beginning in June 1896. The first town school building to house all grades was erected in 1897, followed in 1907 by the Frances Willard High School. The name, for the founder of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, probably reflected the town’s values at the time. The Coast of 1906 reported an enrollment of 275 in Cashmere schools. New high schools were built in 1920, 1959, and 1981. There has been a succession of elementary and middle schools, each replaced as overcrowding necessitated. Many Cashmere residents and alumni lamented the razing of the last distinguished brick high school for a more modern structure. Regardless of buildings, Cashmere schools have an outstanding record of academic and athletic achievement.

In earlier times, however, education was not so sacrosanct as to interfere with the apple harvest. There was often a harvest vacation during which students were let out of school to pick apples. For example, in the fall of 1950, working after school, on weekends, and later during the two-week harvest vacation, students filled 150,000 boxes.

The Wenatchis and their Neighbors

An event of August 20 to 22, 1931, drew the Indians and non-Indians of a wide area together at Cashmere. John Harmelt (d. 1937), the last hereditary Wenatchi chief, had made J. Harold Anderson, a young Cashmere attorney, increasingly aware of the unfair treatment of the Wenatchi Indians following Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens's Walla Walla Treaty of 1855, which effectively deeded Wenatchi land to the Yakama Nation. At the same time, Article X of the treaty provided for the formal establishment of a fishery, the Wenatchapam (Wenatshapam) Fishery Reservation, at the confluence of Icicle Creek with the Wenatchee River at present Leavenworth.

The Wenatchi and Yakamas had always viewed this traditional fishing area as belonging to all the tribes that had shared it for generations. As a result of complex factors relating to the Great Northern Railway’s desired right-of-way and other settler interests, as well as deceptive government dealings with the Indians, the land was eventually sold. Many of the Indians who had occupied these lands for countless generations drifted to reservations, particularly the Colville and Yakama. Only a few remained locally into the 1930s to carry on their traditional life as best they could. Among them were chief Harmelt and his family.

By 1931, the promise of the fishery had still not been honored. Because of this concern, and the impoverishment of the few Wenatchis remaining in the Cashmere area, Anderson, Mark Balaban of Aplets & Cotlets, the Chamber of Commerce, and others helped Chief Harmelt to organize a grand “Pow Wow and Historical Indian Pageant.” Tipis were set up where Yaksum (Yaxon) Canyon meets Mission Creek, and the remaining 250 tribal members traveled to join the few of their tribe still in the Cashmere area, as well as hundreds of other Indians and non-Indians.

Together they participated in games, fellowship, and a re-enactment of the treaty signing. No less a dignitary than Governor Roland H. Hartley (1864-1952) was present. The 89-year-old Chief Harmelt delivered a stirring speech recounting his ongoing efforts to help his people regain their rights and urging the younger tribal members to continue the struggle. On August 13, 2008, the U.S. 9th Circuit Court rendered a long-awaited decision restoring Icicle Creek and Wenatchee River fishing rights to the Colville Reservation Wenatchi, the most numerous descendants of the original tribe.

Another friend of the Indians was Willis Carey (d. 1955) who over his lifetime gained their confidence and developed a vast collection of Indian and pioneer artifacts. A few days before his death on August 31, 1955, several local men concerned about what would become of this collection secured Carey’s agreement that it would become the nucleus of a museum. Virtually every organization in town, under the leadership of Mayor Eric Braun, joined in a committee to found it. As a result, the Chelan County Historical Society was formed in 1956 and the museum opened on June 27, 1959. It now occupies much larger quarters near the east entrance to the town and is part of a “Pioneer Village” composed of many historic buildings moved from their original sites and furnished to interpret pioneer life and skills to visitors. The Cashmere Pioneer Village and Museum is today one of the most respected Indian and pioneer museums in the Northwest.

Tiny's and Aplet & Cotlets

For several decades, a Cashmere landmark was “Tiny’s,” a fruit and cider stand started in 1953 as the Buckhorn Fruit Stand by Richard M. “Tiny” Graves (d. 1971). His business occupied several locations, the most recent and famous on the highway at the east entrance to town. The 400-pound Tiny, “the Cider King,” placed more than 16,000 road signs throughout the West advertising “Tiny’s -- Cashmere, Washington” and “probably sold more apple cider than any other establishment in the world” (Ingraham, 105). After Tiny’s death, friends of his continued to operate the stand. It burned down in July 1972, was rebuilt and reopened in April 1974. Tiny’s officially closed in December 1981.

Even more than Tiny’s, the Aplet & Cotlets Company can be said to have put Cashmere on the map. Early in the twentieth century, two young Armenians fled their native Turkey at a time when rising nationalism there was making life increasingly dangerous for the Armenian minority. Armen Tertsagian (d. 1952) and Mark Balaban (d. 1956) became acquainted in Seattle and decided to go into business together. Attempts at a restaurant and yoghurt factory did not succeed, nor did the young partners like the often gray and damp climate of the Puget Sound area. Heading east in 1915, they discovered Cashmere and were struck with its similarity to their homeland. They bought an apple farm and named it Liberty Orchards in honor of their adopted country. Soon they developed a subsidiary, Northwest Evaporating, for apple dehydration, which greatly lengthened the storage period for fruit. This company benefited not only local farmers, but also the food supply for American troops during World War I. Next came a popular jam called Applum and a cannery, Wenatchee Valley Foods.

The enterprise for which Cashmere became famous, however, is Aplets & Cotlets, the Armenian partners’ idea for replicating a popular Middle Eastern confection, Rahat Locum (also spelled Locoum and known as “Turkish Delight”), made from jelled apple or apricot juice and walnuts. From sales at local gatherings and a small fruit stand in 1918 to the large factory of today, Aplets & Cotlets has developed into a business that ships boxes of a wide variety of fruit-based confections around the world. Its factory now attracts 80,000 visitors per year. During the late 1940s, more of the founders’ Armenian relatives, John Chakirian, Dick Odabashian, and George Alpiar, joined the family firm. Alpiar had been a chemist in the French perfume industry and soon turned his skills to improving products at Aplets & Cotlets. Greg Taylor, grandson of Armen Tertsagian, has been president of the company for 30 years.

Cashmere Holds Its Own

Although Cashmere cannot compete commercially with the big box stores of Wenatchee on the east or the tourist draw of Leavenworth, the “Bavarian Village” to the west, the apple industry, Aplets & Cotlets, the museum, and many small businesses help the town to hold its own. Cashmere also has attempted a signature look for its main street: the American Colonial period.

As the Aplets & Cotlets brochure points out, “Well-scrubbed and friendly, Cashmere is the quintessential Early American small town” (Story of Aplets & Cotlets, unpaginated). In 2002 the residential area along Cottage Avenue was designated a National Historic District because of the architectural integrity of its landscape design and Craftsman bungalow homes dating from the early 1900s.