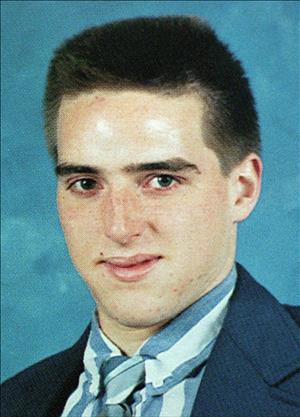

On June 20, 1994, Dean A. Mellberg (1974-1994), age 20, enters the Fairchild Air Force Base hospital annex with a MAK-90 assault rifle and shoots and kills Major Thomas E. Brigham, psychiatrist, and Captain Alan W. London, psychologist, who both recommended his discharge from the Air Force. Mellberg then walks through the hospital and opens fire at anything that moves. He kills two more people and wounds 22 during the murderous rampage before being killed himself by Air Force Security Police officer Andrew P. Brown. It is the worst mass murder in Spokane County history.

The Weapon

The MAK-90, manufactured in China by Norinco (North Industries Corporation), was a modified "sporting" version of the Russian AK-47 semi-automatic assault rifle. (The model designation MAK-90 stood for "Modified AK-1990.") The MAK-90 came with three detachable magazines that each held five rounds of 7.62mm-caliber ammunition. However, the rifle's receiver also accepted a 30-round magazine, called a "banana clip," or a detachable drum magazine, which held 75 rounds.

At 2:45 p.m. on Monday, June 20, 1994, Mellberg arrived at the Fairchild Air Force Base (AFB) hospital from downtown Spokane in a taxicab. Although considered part of the base, the hospital and annex, which housed the psychological services unit, were situated outside the security fence, several hundred yards from the nearest base security checkpoint. The hospital complex was bordered on two sides by base housing.

Mellberg's Rampage

Mellberg, dressed entirely in black, carried a large a large duffel bag containing a MAK-90 assault rifle with a 75-round drum magazine. He entered the hospital annex, took the rifle out of the bag and walked directly to an office shared by Captain Alan W. London, age 40, chief of psychological services at Fairchild, and Major Thomas E. Brigham, age 31, the base psychiatrist. He shot each once in the chest.

Mellberg then turned and marched down the hallway, opening doors and shooting at anything that moved. He left the annex and entered the main hospital, firing randomly as he went. The gunman entered the hospital cafeteria and sprayed the area with bullets, wounding five people and killing 8-year-old Christin F. McCaren. Leaving the cafeteria, he moved into the hospital parking lot and focused on Anita L. Lindner, age 39, trying to flee from the grounds. She was struck by five rounds from Mellberg's assault rifle, the only victim hit more than once.

Acting Fast

Meanwhile, Senior Airman Andrew P. Brown, age 25, with the 92nd Air Force Security Police Squadron, was patrolling the base’s housing areas on a bicycle when he received an emergency call on his two-way radio. He pedaled a quarter-mile to the scene and, while still some 70 yards away, spotted Mellberg shooting at scores of panic-stricken people in the parking lot.

Brown ditched his bicycle and ordered the gunman to drop his weapon. When Mellberg turned and shot at him, Brown dropped into a combat crouch and returned fire with his 9mm Beretta M9 semiautomatic pistol. He fired four rounds at Mellberg; two missed, one hit him in the shoulder and one struck him between the eyes, instantly ending his homicidal rampage. The drum magazine in Mellberg’s MAK-90 still held 19 rounds of ammunition.

The Wounded and The Dead

In the chaotic aftermath of the shootings, reports of the number of causalities varied. Those seriously wounded were taken by ambulance and helicopter to Spokane-area hospitals. A few victims with minor injuries were treated at Fairchild AFB hospital and released. The final tally was five people killed, including Mellberg, and 22 people wounded. However, the following day, shooting victim Michelle Sigmon, age 25, who was five months pregnant, miscarried after the trauma of being wounded.

At 10:00 a.m. on Thursday, June 24, 1994, Chaplains Thomas Unrath and Glen Shaw held a memorial service at the base chapel for those killed in the assault. More than 500 mourners showed up for the service, filling the chapel to capacity. The overflow was directed to a meeting room where the service could be seen on closed-circuit television and onto nearby bleachers where the sermon was broadcast over loudspeakers. Later in the day, individual funeral services were held at various churches in the area. Mellberg's body was cremated and returned to his parents in Lansing, Michigan.

The Investigation

The investigation by the Spokane County Sheriff's Department revealed that on Wednesday, June 15, 1994, Mellberg checked into Arnold’s Motel, N 6217 Division Street in Spokane. He took a taxicab to the home of Michael Carroll, a federally licensed firearms dealer, and purchased a new MAK-90 assault rifle for $450. Only licensed in April, it was already Carroll’s third sale of a MAK-90. Mellberg said he was planning to use the weapon for target practice or hunting. It wasn’t discovered where he obtained the 75-round drum magazine. On Friday, June 17, Mellberg visited a Spokane sporting-goods store and learned how to use the weapon.

At about 2:00 p.m. on Monday, June 20, Mellberg checked out of Arnold's Motel and left in an Inland Cab Company taxi for Fairchild AFB. Marlene Anderson, the motel’s manager, described him as “so unremarkable, she couldn't even tell police what he looked like or what he was wearing when he left the motel” (The Seattle Times). However, she did remember Mellberg was carrying a large duffel bag and a long, white, Styrofoam box wrapped with strapping tape. The cabdriver dropped off Mellberg at the Fairchild hospital at 2:45 p.m., collecting a fare of $36.

Mellberg arrived at the psychological services unit just as Tiffany Williams, age 23, a former Air Force C-141 Starlifter loadmaster, was just finishing her therapy session with Captain Alan London. Suddenly the office door burst open and Mellberg shot London in the chest. When he aimed the rifle at Williams, they locked eyes, then Mellberg turned and left the office. Williams immediately called emergency 911 and reported the shooting. Less than 10 minutes later, 26 people had been shot and Mellberg was dead.

The Spokane Sheriff’s Department conducted a routine investigation into the police-involved shooting death of Dean Mellberg to determine if there was any wrongdoing on the part Senior Airman Brown. On October 4, 1994, the Spokane County District Attorney’s office announced that Brown not only used “lawful and necessary force” to stop Mellberg’s deadly rampage at the Fairchild hospital complex, but also had shot him in self defense.

Mellberg's Disturbed History

Air Force Secretary Sheila E. Widnall ordered an immediate investigation into Mellberg’s military service history. The Office of Special Investigations found that Mellberg had a history of mental problems during his 22 months in the Air Force. In June 1992, he was sent to Lackland AFB in Texas for basic training. While there, he was unable to get along with the other recruits, and an Air Force psychiatrist recommended he be discharged for a “personality disorder.” Instead, Mellberg was graduated and sent to Lowry AFB in Colorado where he was trained in aircraft maintenance.

Mellberg was stationed at Fairchild AFB from April through September 1993. During that time, a dormitory roommate wrote to his commanding officer, complaining about Mellberg’s behavior, which led to another referral for psychological counseling. Captain London, base psychologist, and Major Brigham, base psychiatrist, both considered Mellberg dangerous and recommended his discharge.

Mellberg was sent to the Wilford Hall Medical Center, Lackland AFB, San Antonio, Texas, for further psychological evaluation and treatment. After four months of psychoanalysis, the doctors determined he had serious mental problems, was unfit for military service, and recommended he be discharged.

Mistakes Were Made

Official documents in his personnel file indicated that Mellberg’s parents had contacted U.S. Representative David Lee Camp (R-Michigan), asking him to intervene as the Air Force considered his discharge. On January 4, 1994, a three-member Medical Evaluation Board decided Mellberg suffered from a mild form of autism, rather than paranoia, and recommended he be returned to duty.

On February 16, 1994, Mellberg was assigned to Mountain Home AFB in Idaho, but the chief of the base's maintenance squadron had heard about Mellberg’s troubles at Fairchild, and didn't want him. The next day his orders were changed and he was sent to Cannon AFB near Clovis, New Mexico. He lasted five weeks before he ran into trouble once again and the base commander ordered him undergo another psychiatric evaluation. On May 5, Captain Lisa Snow, chief of psychological services at Cannon AFB, determined that Mellberg was deranged and recommended his discharge. On May 23, the Air Force gave him an honorable, administrative discharge, but with no disability benefits. He was escorted from the base by Air Force Security Police and left at a Motel 6 in Clovis. During the next four weeks, Mellberg traveled to Texas, Alaska, and finally back to Spokane to seek his revenge on the Fairchild AFB hospital and the people he believed had caused his problems.

The Air Force Inspector General’s investigation into Mellberg’s medical history determined the discharge report filled out by Captain John Campbell, a psychiatrist at the Wilford Hall Medical Center, was misinterpreted by the Medical Evaluation Board because the instructions on the form were unclear. Campbell recommended Mellberg “be returned to duty for appropriate administrative disposition,” meaning long-term hospitalization or discharge. Instead, he was kept in uniform and reassigned. To prevent future miscommunications, the Air Force decided to change the form by adding check-boxes for different options such as “Discharge” or “Return to duty.” The fact that Mellberg was allowed to enlist and stay in the military for 22 months, even after mental health experts recommended at least four times that he be discharged or institutionalized, was chiefly ignored.

Psychiatrist Park Dietz, an expert on workplace violence and mass murder, thought the Air Force’s mishandling of Mellberg may have caused him to go postal. According to Dietz, he had “exhibited classic signs of a person who would be capable of avenging perceived wrongs with murderous force.” The signs included “threats, anger, paranoia, blaming others for his problems and making repeated demands for outside investigations into his case ... . One of the most common precipitants of (murders in the workplace) is a poorly handled, conventional termination,” Dietz said (The Spokesman Review).

Honoring Andy Brown

On June 30, 1994, at the direction of President Bill Clinton (b. 1946), Senior Airman Andy Brown was awarded the Airman's Medal for heroism by General John Michael Loh, commander of the Air Combat Command. “It was a hell of a shot,” said Colonel William Brooks, Fairchild’s commander. "At that distance, you're not aiming at a spot, you're aiming at an area” (The Spokesman Review).

He also received an award from the International Police Mountain Bike Association and a certificate of appreciation from citizens of Spokane. And on April 26, 1995, the Air Force presented him with the Colonel Billy Jack Carter Award, given annually to the person who the “who makes the most significant contribution in protecting Air Force people and resources.” Brown eventually left the Air Force and joined the U.S. Border Patrol.

Those killed in the attack were:

-

Thomas E. Brigham, 31 (1962-1994), Major, USAF, psychiatrist

-

Anita L. Lindner, 39 (1954-1994), dependent spouse

-

Alan W. London, 40 (1954-1994), Captain, USAF, psychologist

-

Christin F. McCarron, 8 (1986-1994), hospital visitor

-

Dean A. Mellberg, 20, (1974-1994), perpetrator

-

"Baby” Sigmon, (d. 1994), victim Michelle Sigmon’s unborn child

Those wounded were:

-

Delwyn Baker, 42, Lieutenant Colonel, USAF

-

Pauline Brown, 61, dependent spouse

-

Patrick Deaton, 35, Technical Sergeant USAF

-

Ruth Gerken, 71, dependent spouse

-

Mark Hess, 35, USAF retired

-

Omer Karns, 69, Disabled American Veterans volunteer driver

-

Deena Brackett Kelley, 37, dependent spouse

-

Orsen Lee, 64, US Army retired

-

Dennis Moe, 41, Master Sergeant, USAF

-

Kelly Moe, 15, dependent daughter

-

Marlene Moe, 40, dependent spouse

-

Melissa Moe, 15, dependent daughter

-

Lorraine Murray, 62, dependent spouse

-

Joseph Noon, 30, Staff Sergeant, USAF

-

Hazel Roberts, 64, USAF retired

-

Laura Rogers, 25, USAF active

-

Michelle Sigmon, 25, dependent spouse

-

Samuel Spencer, 13, dependent son

-

John Urick, 69, U.S. Navy, retired

-

Eva Walsh, 57, dependent spouse

-

Anthony Zucchetto, 4, dependent son

-

Janessa Zucchetto, 5, dependent daughter