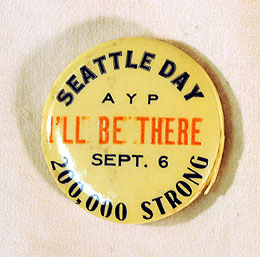

On September 6, 1909, Labor Day, a crowd of more than 12,000 union members and their supporters parade through downtown Seattle. Each profession carries placards announcing its affiliation and many have floats that demonstrate their expertise. Workers focus their opposition on the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific (A-Y-P) Exposition Company rather than on their usual opponents, business owners. The A-Y-P, a world's fair held on the University of Washington campus in 1909, had in the previous two years built several new buildings. Labor leaders chastised exposition management for allowing an open shop, meaning non-union labor could be hired. Although the contractors hired many union members, the open-shop policy antagonized unions, which called for a boycott of the fair when it opened. To make matters worse, the A-Y-P Exposition Company had chosen the traditional Labor Day, September 6, to celebrate Seattle Day at the fair. A general boycott of the fair did not materialize, but on Labor Day thousands of workers attended the parade and a rally that followed at Woodland Park rather than attending the A-Y-P.

Builders Reject Closed Shop

Beginning in 1906, labor unions attempted to work out a contract with the builders hired to construct the A-Y-P buildings and grounds. The builders, organized as the Builder's Exchange, refused the closed shop and wage rate stipulated by the unions. In January 1908 the Central Labor Council in Seattle passed a resolution calling the A-Y-P unfair. In a letter written to the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition Company, the Washington Federation of Labor argued that the open shop policy would lead to an entirely non-union labor force. This would have been particularly disappointing in the face of a recent economic recession that left many unemployed. The exposition grounds and buildings, along with the city's public works projects in preparation for the fair, offered jobs to skilled laborers in the area but without a contract with the Builder's Exchange they had to worry that wages would be lowered by competition with non-union workers, and that outside workers might be brought in.

The Seattle Union Record reprinted the letter and called on Seattle's union members to boycott the Exposition. In the end, however, many of the contractors hired union workers and no wholesale boycott of the fair materialized.

Labor Fails to Halt 2nd Avenue Arch

Labor made a concerted effort to stop one particular project. In June the Seattle City Council hired Strehlow, Freese & Peterson to build a temporary welcome arch over 2nd Avenue at Marion Street. This might have gone unnoticed in the flurry of activity surrounding the opening of the fair but for Strehlow, Freese & Peterson's decision to hire non-union workers. At first the unions blocked the arch's construction by going to court, but that only delayed the project.

The Union Record recounted the parade committee's consternation at trying to plan a parade route that did not go under the arch. In the end, the parade passed under the arch, but, according to The Seattle Times,

"By way of showing their disapproval of the methods said to have been employed in the construction of the arch, several members of the plasterers, painters and carpenters unions refused to walk under it. Making an abrupt detour through the crowd, they rejoined the parade on the other side of the arch" ("Labor Hosts Own City Today," 20)

Unions Protest "Seattle Day" Timing

The next battle between unions and the A-Y-P erupted over the choice of Labor Day for the date of Seattle Day at the fair. Exposition officials seized on the holiday as the perfect opportunity to swell attendance numbers by inviting all Seattle residents to a day in their honor. The unions, however, saw it as an affront to their day, as expressed by the Union Record:

"It is not a coincidence that the same day has been chosen for Seattle Day at the fair, but a scheme to get the workingmen and the money at the fair on the day dedicated to labor by the government and declared a legal holiday by several of the states throughout the Union. Organized labor looks upon this as adding insult to injury, and all union men and their sympathizers are called upon to resent the insult. ... It is our intention to proclaim to the citizens of Seattle that Labor Day is our day, and with it we will brook no interference" ("Labor Day Celebration").

Many editorials and letters filled the pages of the Union Record in the weeks leading up to Labor Day. Some described the unions' preparations for the parade downtown and picnic at Woodland Park and others vehemently criticized the fair's impudent choice.

The Labor Day celebration was a roaring success. More than 12,000 people marched in a parade filled with bands, floats, banners, and clever costumes. The Painters' float in the shape of a palette sported the primary colors while little girls in dresses the colors of the secondary hues rode on top. The Bartenders' float had a bar on it, but, according to the Union Record, "So far as could be discovered from the sidewalk there was nothing doing in the wet goods line on this moving refectory." ("Labor Day a Grand Success," 5)

Each of the unions' members marched together in groups and vied to outdo each other in numbers and enthusiasm. An all-female union, the Waitresses Association of Seattle, marched in line, but discriminatory union-membership rules excluded most non-white workers from participating.

Thousands Attend Rally and Picnic

After the parade wound its way from 4th Avenue and Union Street south to Pioneer Place and back via 2nd Avenue, the crowds went to Woodland Park for a rally and picnic. Tens of thousands enjoyed the park that day, though how many is unclear. The anti-union Seattle Times put the number at 5,000, whereas the pro-union Seattle Union Record counted 40,000 to 50,000.

At the very least many thousands picnicked, played baseball, swam, listened to speeches and bands, and danced. The beneficiaries of the picnic dinners sold, the Waitresses' Home Fund, fared well.

Likewise, Seattle Day at the fair drew a tremendous crowd, with nearly 120,000 flooding the gates. It most likely would have been more had the union members not stayed away, but the unions did not convince the average Seattle citizen to boycott the fair.