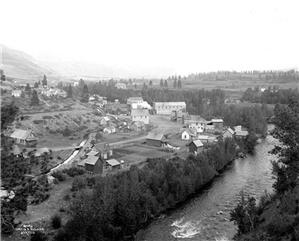

Winthrop, Okanogan County, on the North Cascades Highway, is one of the most historic and scenic towns in North Central Washington. It stands at the confluence of the Methow River with its tributary, the Chewuch (Chewack) River, at an idyllic spot where the Methow Indians once fished and hunted. Next came the miners and trappers who camped in the area. In 1886, when the federal government discontinued the Moses Reservation, to which it had relegated local Indians, white settlers began homesteading in the area. Until the arrival of Easterner Guy Waring (1859?-1936) and opening of his trading post in January 1892, they had to travel miles for supplies. In 1897 it was incorporated as the Methow Trading Company, which expanded the mercantile business and began acquiring land. In 1901 Waring’s Trading Company platted the town, which was finally incorporated in 1924. Earlier, it had been named for another Easterner, Theodore Winthrop. The area suffered its share of fires, floods, and devastating snowfalls and freezes, all of which made a precarious existence even more difficult. With the completion of the spectacular North Cascades Highway portion of State Highway 20 in 1972, the struggling community reinvented itself as a tourist attraction, by restoring old buildings to their early frontier appearance. Even in winter, when the North Cascades Highway is closed, this tiny village of only 373 (in 2007) permanent residents attracts visitors drawn by the unsurpassed scenery, the Old West character, and many recreational opportunities.

First Peoples

Human habitation of the Methow Valley dates back 8,000 to 10,000 years. Before these people acquired horses, they spent the entire year in the valley, wintering in bermed pit houses to protect themselves from the cold. During the rest of the year, they could move about to seasonal camps while living in teepees. For centuries these were covered with tule mats: Later the Indians acquired canvas through trade with non-Indians. With the acquisition of horses during the 1700s, the Methows wintered in warmer areas in order to pasture their livestock. By the time of white settlement, smallpox had drastically reduced the population of the Northwest tribes, including the Methows.

In 1871, the remaining Methows, along with many other tribes of the Columbia Plateau, were assigned to the Colville Reservation. Later, through the efforts of Chief Moses (b. ca. 1829), the federal government agreed to the creation of a reservation specifically for the Methows and adjacent Columbia Plateau tribes. Thus in 1879, Columbia (or Moses) Reservation was created, but Moses and his people never moved onto it. The reservation itself was as short-lived as portions of the Colville Reservation coveted by white miners and settlers.

In 1883, the government removed the Columbia Reservation from maps, and on May 1, 1886, the lush, beautiful Methow Valley was opened to white settlement. Much to the dissatisfaction of other tribes already on the Colville Reservation, Moses and his people were moved there. Yet as late as the 1940s, some of the Methows continued their seasonal migrations to traditional fishing, hunting, and gathering areas now occupied, though sparsely, by white settlers. Although there was an “Indian scare” in 1891, written memoirs and oral histories of the old-time settlers recall basically amicable interactions between the two peoples.

Founding a Town and Getting There

Fur traders, trappers, and then miners made their circuitous way into the Methow Valley and the mountains surrounding it. Arriving in 1886, trapper brothers Tom and Jim Robinson were the first known white settlers in the area that became Winthrop. The next were James Sullivan and his wife Louisa Heckendorn Sullivan, who arrived in 1887, settling an area adjacent to present Winthrop that came to be called Heckendorn and is now part of the town. The Sullivans also built the first hotel in Winthrop. Walter Frisbee arrived in 1888 and eventually set up a blacksmith shop, a trading post, and a photography shop. Next came the homesteaders intent on establishing small farms and permanent communities. The early settlers found land and climate conducive to cattle ranching, and there was a ready market for beef in the nearby mining operations or for shipment to Seattle via Wenatchee. As pioneer Flora Jones recalled, “Food for the family was raised and prepared for winter and hay for stock. There was no market for anything except beef” (Rohn, 5).

Few regions of Washington were as isolated as the Methow Valley. The Cascade Mountains presented an almost insurmountable barrier on three sides. Although the Indians had developed routes west to the coast, they were not practical for settlers with wagons loaded with goods and families. From the east, there was no trail along the Methow River from the Columbia because, during part of its course, the river flowed between steep canyon walls. Some settlers took the train to Spokane, Sprague, or Ellensburg and came overland from there, a route that involved a horrendous crossing of the Columbia. One such settler was Guy Waring, founder of Winthrop, who brought his family to Washington twice, in 1884 and in 1891. His stepdaughter, Anna Greene Stevens, later recalled both crossings of the Columbia River. During the first:

“We spent five days alone crossing the Columbia River, a perilous and awesome undertaking. The river, undimmed in those days, boiled downstream at an unbelievable speed. Indian dugouts were used to make the crossing. They were hollowed-out logs with the bark still on them. There was no bow or stern. They were treacherous, and only the extreme skill of the three Indian paddlers made the crossing possible. The covered wagons had to be taken completely apart and carried across in pieces. Two dugouts were tied together to accomplish this feat” (Portman, 105).

By the time of the family’s 1891 crossing, there was a cable ferry at the site of present Wilbur “that a covered wagon could drive onto, which crossed the river attached to a trolley. The boat, hauled at an angle against the swift current and held by the trolley, sailed across by water pressure” (Portman, 105).

Pioneers arriving over the Chiliwist Trail, an Indian path that became the main link between the Okanogan and Methow valleys, had to ford the Okanogan River and then cross the mountain ranges between the Okanogan and Methow valleys. This former Indian trail was safe by foot, tolerable on horseback, but an almost impassable two and a half days by wagon. Yet a more direct route along the steep-sided Methow River was impossible until, in 1891, settlers from Winthrop, Twisp, and Carlton donated money and their own labor to complete the Bald Knob Route, a primitive road that avoided the canyon cliffs by following the hillsides. It was still so difficult for freighters that another alternative, the narrow Brewster Mountain Road, was completed the same year. It was scary but good enough to enable stagecoach service between Brewster and Winthrop.

A Real Road To Winthrop

Not until 1904, when Walter A. Bolinger was elected to the state legislature, did the idea of a river-level road along the Methow take hold. In 1905 he proposed it as a state highway. With funding from the legislature, the sweat of convict labor, and plenty of dynamite, a river-level road was completed in 1909 from Pateros on the Columbia to Robinson Creek 20 miles beyond Winthrop. In 1905 the Washington State Highway Department was created, and the Methow Valley road was the first highway built by the State of Washington. It was paved by 1938. This road crossed the river at several points. When the disastrous flood of 1948 wiped out all the bridges, the only access east from Winthrop was over the old Brewster Mountain Road until these bridges were repaired.

From its first days, the state road connected with the steamboats that plied the dangerous stretch of the Columbia between Wenatchee and the mouth of the Methow from the early 1890s until 1914. This combination of road and river travel eased the isolation of the region, bringing settlers and supplies into the Methow Valley and transporting the products of their mines, sawmills, and orchards to market. The journey from any part of the valley to Wenatchee now took less than two days! Custom-made wagons transported freight until the first trucks began operating on the route in 1915. During World War II, Joe Lockart of Winthrop introduced a popular passenger bus service between Winthrop and Wenatchee that continued until 1966. For years, beginning in 1916, there was talk that ultimately came to nothing of a spur railroad linking the valley to the outside world. Not until completion of the North Cascades Highway in 1972, was Winthrop connected directly and easily to Western Washington.

Waring and His Trading Co.

In the fall of 1891, Guy Waring, a 32-year-old Harvard graduate, arrived in Winthrop with his wife, Helen Clark Greene Waring (d. 1906), and his three stepchildren. It was his second attempt at settling in the West. His first had been a stint of ranching and storekeeping beginning in 1884 in the Okanogan Valley near the Canadian border. These first Western adventures are described in his My Pioneer Past, published in 1936. Then from 1888 until 1891, Waring and the family were back in Boston.

Upon arrival in Winthrop, Waring housed his family in a tent until completing a log cabin. His helpers soon built a trading post, which Waring opened in January 1892. In 1897, with backing from Eastern investor, it was formally incorporated as the Methow Trading Company. A post office had been created on June 18, 1891, with Charles Look as first postmaster. Waring took over the position in early 1892 and angered some of the locals by requesting that the name of the town be changed to Waring. It already bore the name of Theodore Winthrop (1828-1861), a Yale graduate who had rambled about Washington Territory and in 1853 published Canoe and Saddle describing his adventures.

Although his neighbors nursed some animosity toward Waring, they did welcome his general store, which greatly simplified their access to supplies. Before it opened, the closest source was Coulee City, a four-day round trip by wagon. Residents of Winthrop and the surrounding country continued to patronize his mercantile company for decades. Waring opened additional branches and trading posts at Pateros and Twisp and in several of the mining districts in the surrounding Cascades. However, by 1910, he was overextended and consolidated his mercantile business at Winthrop.

Although most funding of the new corporation came from Boston investors, Waring was elected president and retained almost exclusive control.

Waring soon built his family a larger log home, which locals dubbed “the castle” because of its relative size and commanding position on a hillside overlooking the town. It now houses the Okanogan Historical Society’s Shafer Museum, one of the best regional museums in the state. Waring also established a sawmill and later a gristmill.

In 1897, the Methow Trading Company acquired Waring’s Duck Brand Saloon, although he continued to manage it. Waring had opened the saloon, named for his cattle brand, not because he wished to become a saloonkeeper, but because he wanted to preempt other more disreputable establishments. He had had his fill of violence and drunkenness in the Ruby mining area near Loomis during his previous sojourn in Okanogan County. This saloon, with its strict rules about hours of operation and standards of conduct, further alienated Waring from many of the locals. It was never profitable and closed in 1910. The building that housed the Duck Brand saloon is now Winthrop’s town hall. Today a popular Winthrop restaurant calls itself the Duck Brand.

Twice during his early years in Winthrop, Guy Waring entertained a visitor who would soon become famous: his Harvard classmate Owen Wister, who visited him in 1892 and 1898. Wister became a best selling author in 1902, with his The Virginian, the first true Western novel. Although the setting was Wyoming, there is evidence that some of the characters and incidents are based on people and events Wister encountered in Winthrop.

Waring’s business and Winthrop prosperity temporarily stalled when President Grover Cleveland issued an executive order on February 22, 1897, placing the entire Methow Valley within the Washington Forest Reserve. This edict permitted residents to remain but prohibited future settlement. Waring and others mounted a vigorous protest, arguing that, unlike the surrounding mountains, the Methow Valley was agricultural and did not contain forests in need of protection. In 1901, the valley portion was released from the Forest Reserve system. Today the Methow Valley is a corridor of private property mostly surrounded by National Forest land.

Mining had begun in the Harts Pass area northeast of Winthrop when Alex Barron struck gold in 1892. The boomtown shacks of Barron soon housed more than 1,000 people. Waring established a branch store, but the shipment of goods was difficult and unprofitable because the road built to Barron by Colonel W. Thomas Hart (b. 1836) was nearly impassable. Goods and supplies coming up to the mines and ore coming down had to be transferred to pack horses at the point where the trail became too dangerous, narrow, and steep for freight wagons. Gold and silver mining continued off and on in the area, but the resulting trade never contributed much to the prosperity of Winthrop. Many huge pieces of antique mining equipment from the abandoned Harts Pass mines were later transported by helicopter for display on the grounds of the Shafer Museum in Winthrop.

Progress and Difficulty

Waring’s mercantile company, with the investment of Eastern backers, bought up townsite land, and in 1901 platted the town of Winthrop. Lots sold quickly, and Waring and Winthrop entered a period of prosperity. By 1904 David Heckendorn had platted the townsite of Heckendorn a half mile downriver from Winthrop. Chauncey McLean’s general store in Heckendorn competed with Waring’s Methow Company. Winthrop got its first newspaper, the Winthrop Eagle, in 1909. Three year later, it became the Methow Valley Journal. In 1912, the community built a handsome school of locally hewn rock and locally made brick, which was destroyed by a fire on January 1, 1961. In 1924, over some local objection, Winthrop was reincorporated to include Heckendorn and another plot of land, Carl Johnson’s Addition. Roma Johnson was the first mayor. That same year, electricity came to the area, with the Upper Methow Valley Power and Light Company power plant.

Waring’s final and most consuming venture in the Methow Valley was a ranch he bought in 1904. His efforts over the next 12 years to grow apples profitably drained proceeds from the trading company. A drought beginning in 1915 finally doomed the L5 Orchard. By 1916 Waring had lost control of the Methow Trading Company and in 1917 returned to Massachusetts, seemingly a failure. The company struggled on during a protracted liquidation process until 1934 when it was dissolved altogether.

Yet Waring could look back with some nostalgia on his years in the West, recalling at a 1932 Harvard graduation anniversary, “I had a hard but beautiful life for most of the time spent on the frontier; but came away with pleasant memories of the climate; and with love for the beauty of the country” (Portman, 214, 215). Furthermore, the presence of the Methow Trading Company, although it ultimately failed, contributed to the survival of a precarious community in the remote Methow Valley.

Whether earning a living through agriculture, mining or timber, the residents of the Winthrop area had always worked hard with little to show for it. The onslaughts of nature worsened their situation. There were disastrous floods in 1894 and 1948. The drought that began in 1915 killed more orchards than Guy Waring’s. Even before then, ranchers at Winthrop had attempted irrigation. Although irrigation became a major factor in the lower and central Methow Valley, the early ditches around Winthrop did little more than “turn what would have been starvation ranches into at least a living,” according to pioneer Walter Nickell (Portman, 263). Then a severe freeze in 1968, during which temperatures plunged to 50 below zero, wiped out most of the remaining apple orchards in the upper Methow Valley.

Winthrop's Revival

Winthrop desperately needed a revival. It came about for two reasons: the completion in 1972 of the North Cascades Highway, which “became popular with Puget Sound-area tourists who thrilled to its expansive alpine vistas,” (Pigott, 125) and the restoration of the town’s business district to a Western theme. Even before completion of the highway, Otto Wagner, lumberman and sawmill operator, and his wife Kathryn (Kay) had proposed the idea. Otto Wagner did not live to see the realization of the project, but Kay carried it through to completion. She hired Leavenworth architect Robert Jorgensen, artists and builders; local merchants all contributed generously to the restoration of Winthrop. The process involved meticulous research of local historic photographs and travel to see examples of other Western towns.

The goal was authenticity, not a Hollywood set. The frontier theme town was ready for the first Western Washington tourists to arrive over the North Cascades Highway. Yet Kay Wagner’s objective was never strictly tourism: “I don’t like to call it a tourist attraction,” she said. “This is a living town. People live in it. They aren’t tourist attractions” (Portman, 200).

Since the 1970s, many who visited Winthrop and the Methow Valley decided to stay. Vacation getaways and year-round homes of retirees have sprung up around Winthrop and throughout the valley. The impact of these people is not just economic. Energetic retirees, whether lifelong residents or newcomers, provide volunteer staffing for the museum, the library, the information center, and such annual events as the superb Methow Chamber Music Festival.

The nonprofit Methow Conservancy, with headquarters in Winthrop, is dedicated to “inspiring people to care for the land of the Methow Valley” by means of conservation easements that have protected 18.3 miles of critical riparian shoreline habitat along the Methow River and its tributaries. These easements “help families keep their farms and ranches and protect the open space and scenic views that regularly draw tens of thousands of visitors to the Valley” (Methow Conservancy website). Winthrop hums along within this beautiful valley that Owen Wister called “a smiling country, winning the heart at sight” (Portman, 11).