The Washington Forest Protection Association (WFPA) was incorporated on April 6, 1908, and celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2008. For its first 50 years the association was known as the Washington Forest Fire Association (WFFA). In 1958 the WFFA reincorporated and became the Washington Forest Protection Association (WFPA). This essay discusses the firefighting technology used by the association during its first 70 years and explains how improvements in technology dramatically reduced damage caused by wildfires. During the 1970s, the WFPA evolved from primarily a firefighting organization into more of a political organization, and by the late 1970s the change was so complete that the WFPA was no longer as involved with advances to firefighting technology as it had been in the past.

Early Efforts

In September 1902 the Yacolt Burn, the largest forest fire in recorded state history to that point, burned more than 370 square miles of timber worth up to $30 million in 1902 dollars (more than $600 million in 2008 dollars). This disaster resulted in the first organized efforts to establish fire protection in the state. Early in 1908, leaders in the timber business, including George S. Long (1853-1930), General Manager of Weyerhaeuser Timber Company, mailed 800 letters to timberland owners inviting them to form a voluntary association to suppress forest fires. Twenty-two companies responded and incorporated the Washington Forest Fire Association (WFFA) on April 6, 1908. The five incorporators of the WFFA were George Long of the Weyerhaeuser Timber Company, E.G. Ames of the Puget Mill Company (now Pope and Talbot), Michael Earles of Puget Sound Mills and Timber Company, T. Jerome of the Merrill & Ring Lumber Company, and D.P. Simons Jr., who became the first chief fire warden of the WFFA. The association’s first office was located in the Colman building on 1st Avenue in Seattle, and George Long was the WFFA’s first president, serving in this position until March 1930.

Chief Fire Warden Simons organized a force of 75 men, each of whom was equipped with an axe, a planter's hoe, and a 10-quart water bag (for the fire crew). Seven fire districts were established, stretching east from the coast to the Cascades, and north from the Columbia River to the Canadian border. Patrols were mostly on foot or horseback, though there were also “motor-cycles” (1908 WFFA Annual Report, p. 7). William “Billy” Entwistle went to work for the WFFA in June 1908, two months after its inception, and in a letter dictated years later to his wife, explained patrolling in those early years:

"In patrolling everyone was on foot. There were no stages, no autos, sometimes you could take the train one way and walk back. The chief warden got me a horse — that wasn’t satisfactory since both the horse and I were worn out. The next year they got me a bicycle. But between the steep hills and impassable roads, I was carrying the bike half the time. The third year I went on foot and had nothing to bother me. I could take off through the woods anywhere. Since the roads were not ready yet for other transportation I could accomplish more that way.”

But technology was already leaping ahead. In 1909 the WFFA added six motorcycles, a motorboat, and a saddle horse to its complement. The boat operated along Hood Canal and provided not only an effective patrol for fires but also a handy taxi service. In 1910 the WFFA took it a step further and provided two of its inspectors jointly with a small automobile, the association’s first: “This proved invaluable and we hope to equip all inspectors with these machines in 1911” said the 1910 WFFA Annual Report, but the hope turned out to be a few years premature.

During the early 1910s, WFFA rangers visited logging camps in Western Washington, encouraging loggers to install spark arresters on donkey engines and locomotive engines, since sparks flying from these engines were a frequent cause of fire. Also during the early 1910s, many locomotives switched from wood or coal-burning engines to oil-burning engines, which greatly reduced the risk of flying sparks. But even small fires often quickly mushroomed out of control, and if they weren’t spotted quickly they turned into big fires. The sheer size of the WFFA’s territory made early detection especially difficult for a fire that started in a remote location. One hundred years ago Western Washington’s population was much lower, transportation far more difficult, and when a fire started deep in the forest, many times no one was aware of it until it had grown into a raging behemoth.

Lookout Towers, Portable Pumps, and Fire Trucks

To counter this problem, the WFFA began building lookout houses on Western Washington mountaintops later in the 1910s. At least one lookout house (on Kiona Peak, in eastern Lewis County) was in use as early as 1916 or 1917. Several more were built during the final years of the 1910s. This effort accelerated in the latter years of the 1920s and in the 1930s, when dozens of lookout towers were built in Western Washington. Popular both with rangers and with people who just enjoyed climbing them for the spectacular views (though some early towers lacked stairs, requiring lookouts to rappel up the tower), these lookout towers and houses were used for nearly half a century, until they were replaced by aerial reconnaissance beginning in 1967. Although some lookouts prided themselves on being able to locate a fire based on simply a visual sighting, many of them used an Osborne Fire Finder to find a directional bearing for smoke in order to more accurately direct firefighters to a fire. The Osborne Fire Finder works by use of a sight and a map, and sightings from multiple towers can be used to more precisely fix the location of a fire.

In 1914 the WFFA arranged on a temporary basis to receive weather forecasts from a weather office in Portland whenever dry easterly winds, which carried the greatest threat of fanning fires, threatened. The value of this program was obvious after this trial run, but fire weather warning services were not placed on a permanent basis by the Weather Bureau (now National Weather Service) until July 1926.

Winds and hot weather had long been known to provide fuel for fires, but in 1923 the U.S. Forest Service published a paper demonstrating for the first time that low relative humidity (below 35 percent) also had a big impact on fire hazard. To counter this problem, the WFFA in 1924 began telegraphing fire warning forecasts to loggers and others. The association also began equipping its observation stations with weather equipment, and encouraging loggers to equip their camps with hair hygrometers, which used strands of hair (with the oils removed) attached to levers to amplify changes in hair length, since hair lengthens as humidity increases and contracts as it drops.

But it was technological advances in the 1920s that had the most impact on reducing fire damage. After a particularly disastrous fire season in Western Washington in 1922, area manufacturers became more interested in developing better ways to fight fires, and began developing more and better portable gasoline-powered pumps. Local companies quickly found a ready market for these pumps: In 1923 alone the WFFA purchased a dozen portable pumps, each weighing between 80 and 140 pounds, each equipped with 1,000 feet of hose, and with pumping capacities of 13 to 40 gallons a minute, depending on the unit used. Lighter and better pumps came out in 1924, and were a hit not only with the WFFA but also with many logging operators. These durable pumps were particularly effective in putting out small fires before they blossomed into larger ones, and caught on fast: “On many occasions the little tripod pump [a Pacific-Ross pumper] has done the work of twenty or more men in extinguishing stubborn fires. They are now considered a necessary part of the fire-fighting equipment” (1925 WFFA Annual Report, p. 16).

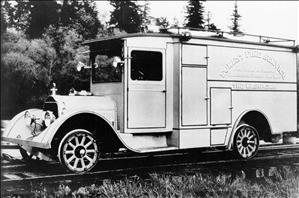

In 1925 the WFFA purchased its first truck, a Graham Brothers one-ton, on which were installed three gasoline-powered pumps (one weighing 500 pounds) and 3,000 feet of fire hose. The truck was difficult to drive in wooded terrain but was useful in providing water to smaller firefighting units, and in 1926 the WFFA bought another seven trucks. These truck pumps had far more pumping capacity -- up to 300 gallons per minute -- than the smaller portable pumps. Since roads into the forest were limited, at least two of these trucks had their tires removed and replaced with flange rims, which enabled them to operate on railroad tracks and penetrate more deeply into the forest where the trucks could not otherwise go.

Tank pumps followed in 1928, which were good for not only fighting fires but in setting back-fires when filled with coal oil. (A back-fire is a fire set along the inner edge of a fireline to consume the fuel in the path of a wildfire and/or change the direction or force of the fire's convection column.) Before then back-fires were set with a pressure torch -- essentially a flame thrower -- which was difficult and dangerous to use. In 1929 the WFFA bought its first tractor (a 15-horsepower Caterpillar) and built a plow for it; this equipment was beneficial for building fire lines and performing other necessary tasks. “Where this equipment could be used, it was faster and more efficient than a crew of 50 men” writes Chief Fire Warden Charles Cowan in his book of the WFFA’s first 50 years, The Enemy Is Fire!

Chemical Spraying and Big Trucks

In 1927 the WFFA began to experiment with universal fire-hose couplings. Before this time, hose couplings used “male-female” ends, which caused a problem if (as often happened) the end of the hose meant to connect to the water pump was run out to fight a fire, because the hose’s other end would not connect to the pump. In these circumstances as much as 1,000 feet of hose had to be reversed, resulting in a serious loss of time. By 1930 these universal couplings were in widespread use. The 1930 WFFA Annual Report noted that using the new coupling saved at least 15 minutes of time per 1,000 feet of hose, and could be coupled and disconnected even when the pump was operating.

The year 1931 saw the WFFA undertake an aerial-dusting operation to combat the hemlock looper in Southwestern Washington’s Pacific County. The hemlock looper is a moth that in its larvae stages is a defoliator, and very destructive to hemlock, Douglas fir, and spruce trees. Aerial dusting was still a rather new operation in the early 1930s, particularly an operation as large as this one that involved between five and six thousand acres. The WFFA designed both its own airplane hopper capable of dispersing 1,000 pounds of calcium arsenate per trip, and a separate, 14-foot-tall hopper to load the airplane hopper (this 14-foot hopper was built and stationed on the beach at Long Beach in Pacific County, since the beach made an excellent landing field). The WFFA contracted with the Northwest Air Service of Seattle to dust the affected areas. One hundred twenty flights were flown in a Ryan monoplane, similar to the “Spirit of St. Louis” airplane flown by Charles Lindbergh in his solo flight across the Atlantic four years earlier. The next year the results were reported to have been “at least partially successful” (1932 WFFA Annual Report, p. 14).

By the mid-1930s, the WFFA’s firefighting efforts were paying off. Although the annual average of total number of fires in the state remained relatively steady (in the high 700s), the total number of acres burned each year began to plummet from its annual average between 1920 and 1935 of 120,357 acres. Further gains were realized in 1939 when the WFFA began using portable pumps installed on some of its pickup trucks to fight fires. These pumps, one driven by the truck’s fan belt and the other by a power take-off (a driveshaft used to draw power from the engine to the pump), were so successful that this program was quickly enlarged to include all WFFA patrol trucks in 1940. The trucks were equipped with three 55-gallon barrels of water which could be refilled from a nearby water source, and in 1940 alone the portable pumps contributed to keeping fully 50 percent of all fires on association land to less than one-quarter of an acre. Tank trucks came along for the WFFA in 1946 when the association converted two International trucks into tank trucks, each equipped with 500-gallon sheet metal tanks.

The WFFA tried chemical spraying of roadside alder growth for the first time in 1948. The results weren’t much: “We apparently still have much to learn about this method of keeping protection roads alder free,” dryly remarked the 1948 WFFA Annual Report. The WFFA had better luck with spraying in 1949, and by 1950 had the technique down to where it was found to be more effective than cutting the trees. In 1951 the WFFA moved further into the future and participated in the new technique of cloud seeding with silver iodide in an effort to generate more rain. Cloud seeding experiments continued in 1952, but with few significant results other than generating considerable public interest, and the WFFA discontinued its rainmaking efforts after that year.

Airplane Patrols and Two-Way Radios

In 1952 the WFFA hired a Cessna 170, equipped with two powerful loudspeakers and an amplifier, to fly over Western Washington’s forests and campgrounds warning of fire danger. The message was loud enough to be heard for a range of two to three miles. Four round trips over Western Washington during the year cost the WFFA $356, and made such a public impression that a story about it was not only featured on the new medium of television in Seattle, but later in the year the State Division of Forestry hired the same plane and equipment to do the job in Eastern Washington.

The WFPA quickly appreciated the ability of television to reach a large audience, and in 1956 used television as part of its fire prevention efforts by requesting that KING-TV broadcast forest-fire information each evening at 6:50 p.m. to alert the public to the next day’s expected fire danger. KING-TV agreed. The forecast for the next day’s fire danger rating was phoned into the station each evening by a representative of the State Division of Forestry, and displayed on a replica of the fire-danger rating board during the broadcast.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, a number of local firefighting associations (such as Rue Creek and Trap Creek) developed. These smaller associations were interested in having firefighting protection directly available within their immediate boundaries in the event of fire rather than having to risk waiting hours for it to arrive from another location, and the WFFA provided this protection through agreements negotiated with these associations. By 1954 at least one of them, the Rainier Forest Association, was using an airplane patrol to spot fires. The trend of airplane patrols slowly spread over the next decade and by the mid-1960s were becoming commonplace, indeed so commonplace that in 1967 aerial reconnaissance for fires began replacing lookout towers in Western Washington.

The WFFA first equipped two of its field inspectors’ cars with two-way radios in 1951. Tuned in to the State Division of Forestry frequency, the radios enabled the association’s field men to keep in touch with various lookouts, obtaining first information on new fires and relaying it more quickly. By 1959 these radios were in most inspectors’ cars and had become an integral tool in the fight against fire, providing not only early notice of fires but also more accurately and quickly directing crews to their location.

The WFFA reincorporated as the Washington Forest Protection Association (WFPA) in January 1958. By coincidence, a year earlier the Legislature had created the Department of Natural Resources (DNR), and the DNR had taken control of forest-fire prevention and suppression on public and private lands. These changes were a harbinger for a series of sweeping changes that would transform the newly minted WFPA into a far different organization from what the WFFA had been. The new WFPA would evolve from a fire-protection organization into one that would be far more involved in legislative matters and public information projects than its predecessor had been.

Tanker Planes, Helicopters, and Fire Simulators

The changes were relatively subtle during the 1960s, and during the decade the WFPA continued to devote a large amount of its effort toward fire prevention. Two significant developments took place in 1963. First, the WFPA and DNR leased a water-scooping PBY aerial tanker (which had originally been used 20 years earlier during World War II) for three months, and stationed it in Kelso (Cowlitz County), Washington. The plane, nicknamed “Scooper I,” could carry 1,000 gallons of water. It was used on five fires that year, and “its performance generated widespread enthusiasm” (1963 WFPA Annual Report, p. 17). Second, Dow Chemical released a new gelling powder which when mixed with water formed a gelatinous mass. When this gel was dropped from a plane it clung to forest fuel to provide a wet covering layer. The PBY tanker used the gel on one fire in 1963, and the results were so favorable that it was used more frequently in ensuing years.

In 1967 the PBY tanker was not available, so the WFPA and DNR leased a twin-rotor, Kaman 600 helicopter. The helicopter could carry 250 gallons of water in a container slung from a cargo hook under the aircraft, and was capable of delivering 5,000 gallons of water per hour, provided the water source was within a mile of the fire. The helicopter was so effective that in 1970 four such “ships” were stationed at strategic points in Western Washington. They provided a significant edge in keeping smaller fires in check, particularly in situations where the helicopters could get to the fire before firefighters could. In 1973 the DNR assumed full responsibility for providing the helicopters.

In 1967 the U.S. Forest Service allowed the association to use its forest-fire simulator located in Redmond, Oregon, for training purposes. Realistic forest-fire problems were simulated and resolved on the machine, and the simulator was so useful that in 1968 it was moved to the DNR training building in Shelton (Mason County). It was used yearly for training through at least 1976, with the WFPA conducting a fire simulator course annually in cooperation with the DNR.

Transition and Accomplishment

The early 1970s saw an accelerating series of sweeping state and federal laws which had a tremendous impact on forestlands. As a result, during the decade the WFPA transitioned from a fire-protection organization into more of a political organization in order to more effectively respond to its members needs. By the late 1970s the transition was so complete that the WFPA was no longer as involved with technological changes and advances in firefighting as it had been in its past.

But the WFPA could look back on its work at preventing and controlling fires over the prior 70 years with a sense of accomplishment. In 1970 the WFPA Annual Report noted that the 20-year average between 1950 and 1969 of total number of acres burned in fires annually on association land was 4,480 acres. This was a 96 percent decrease from the 15-year period of 1920 to 1935, when the annual average of acres burned exceeded 120,000. Yet the annual average of total number of fires remained largely unchanged at nearly 800, providing solid proof of the association’s success in fire prevention and firefighting techniques as well as advances made in firefighting technology over the course of half a century.

Ironically, by the 1960s people had begun to recognize that fire actually played an important role in a healthy ecosystem, and in 1968 the National Park Service began allowing natural fires to burn in some areas and to employ some manager-ignited fires. This idea was not without controversy. Still, we now know that active forest management -- thinning small trees and clearing brush, followed by controlled burning -- not only reduces the risk of a major fire but also restores ecosystem health and improves habitat quality.