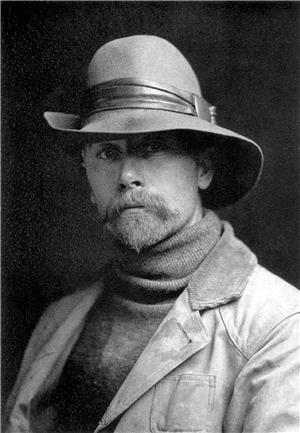

Edward Curtis was one of the most prominent figures in the cultural history of Washington. He is acknowledged as one of the leading American photographers of his time and has produced iconic portraits of many historical figures such as Chief Joseph, J. P. Morgan, and President Theodore Roosevelt, who was among his most ardent supporters. Best known for his epic 20-volume book, The North American Indian, Curtis also served as Seattle’s finest commercial and portrait photographer in the early twentieth century. His studio became a nexus for important figures when anyone of prominence visiting Seattle made it a point to be photographed by the famed master. His studio was also the starting ground for several regional photographers who would go on to establish international reputations in their own right. These included Imogen Cunningham, Ella McBride, and Frank Asakichi Kunishige. Asahel Curtis, Edward’s brother, also became a noted photographer who concentrated on commercial landscape and documentary photography as well as poetic studies of Mount Rainier.

Nature and Photography

Edward Sheriff Curtis was born in Wisconsin on February 16, 1868. He was the second son of Ellen Sheriff Curtis and Civil War veteran Johnson Asahel Curtis. As a result of the war, Johnson Curtis had suffered health problems that limited his ability to work. Unable to exert himself through physical labor, he first moved his family to Minnesota, where he became a preacher. He nurtured Edward’s shared love of nature and encouraged his inquisitive mind. Around this time, Edward became interested in photography and built his own camera by the age of 12.

Edward and his father initially came to Port Orchard in Washington Territory by 1887 in preparation for the arrival of the remaining family members who would join them the following year. Unfortunately for the elder Curtis, he died shortly after his family relocated to Washington, leaving Edward responsible for their support.

First Studios

Edward's interest in photography continued to grow and around 1890 he purchased his first professional camera. Sensing an opportunity for a new profession in this field, he moved his mother and siblings to Seattle and went into partnership with Rasmus Rothi, opening his first professional studio.

In 1892, Edward married Clara Philips whom he had initially met as his caregiver following a work-related accident that had left him debilitated for several months. He ended his unsuccessful partnership with Rothi and that same year began a new association with Thomas Guptil. Curtis & Guptil would soon to become the leading photographic and engraving studio in Seattle.

Curtis’s career coincided with the growing interest in Pictorialism in the United States. Pictorialsm is the name used to describe the artistic use of the camera as opposed to its purely documentary function. His work soon appeared regularly in the important camera journals of the period such as Camera Craft, the West Coast’s leading photography publication. Other contemporaries such as Carl Moon and Emma B. Freeman often included idealized Native American studies for subject matter as well.

Curtis observed the evolving Native American culture first-hand in the Northwest and his first Native American image was purported to be a portrait of Princess Angeline (Kikisoblu), daughter of Chief Seattle (Ts'ial-la-kum), whose name is the derivation for the city of Seattle.

Local interest in pictorial photography began to grow and in 1895 the first Seattle Camera Club was formed. Members of some of the prominent pioneer families such as the Denny’s became involved in the medium and sponsored successful local exhibitions but there are no extant records of Curtis's involvement in these art related organizations or events.

By 1896 Curtis & Guptil had become the pre-eminent photography studio in Seattle, but the partnership dissolved the following year with the latter’s departure. The studio was renamed Edward S. Curtis, Photographer and Photoengraver.

Achievement and Eminence

Within a few years, Curtis was winning national competitions for his photography and his nature-inspired writings began to be published, sometimes illustrated with his own work.

In 1897, Curtis was selected to lead a climbing expedition up Mount Rainier that was sponsored by the Portland, Oregon, group, Mazamas. As one of the first large parties to climb the mountain, his involvement witnessed several experiences that would alter the course of his life. The expedition had included some legendary early climbers such as Philemon Beecher Van Trump and Hazard Stevens. This was also the first recorded tragedy on the mountain when Professor Edgar McClure died on the descent after taking the first accurate measurements of the mountain.

This climb was also important as it marked his first association with Ella McBride, who would later join him in Seattle as his assistant and manager of his studio. McBride later recalled that she, Curtis, and a group of climbers from that expedition formed a core group of concerned citizens who lobbied for the preservation of Rainier until it was made a National Park in 1899.

Although both Curtis brothers were now gaining attention in their field, their relationship soon turned rancorous when Asahel, who had worked as an engraver in the Curtis Studio, traveled to Alaska to cover the Gold Rush in 1898. After Edward published Asahel’s photographs as his own work, the two brothers parted ways. They never reconciled.

Through his mountain climbing activities, Curtis met and befriended George Bird Grinnell an important early environmentalist credited with providing the impetus behind the founding of the National Audubon Society. Through his connections, Curtis was invited to join the 1899 Harriman Expedition to Alaska as official photographer.

Documenting Native American Culture

The following year, Curtis began to travel outside of the state to experience and document Native American culture.

In 1903, he began seeking funding for his documentary project without much success. He recruited the talented photographer Adolph Muhr to manage his studio, allowing him the freedom to travel and develop the series that he had envisioned. Muhr was a technical master and particularly adept in platinum printing, being a source of inspiration to the young Imogen Cunningham in the early years of her career. In June of 1904, the Woman’s Century Club in Seattle sponsored the First Annual Exhibition and Sale of the Industrial and Allied Arts of Washington. Curtis was honored with a solo exhibition of his work at this venue where painting and crafts predominated.

During these years of travel, Curtis photographed sacred dance ceremonies and produced portraits that included the legendary Geronimo. He exhibited his work in New York to increase its visibility, with the intention of locating funding for his book project that was rapidly escalating in cost. With an encouraging letter of recommendation from President Theodore Roosevelt, Curtis finally acquired the financial support he needed from the wealthy railroad magnate, J.P. Morgan.

The first several volumes of the book indicated that the project would be successful and he soon received another endowment from Morgan to proceed with the next volumes.

Gaining Visibility

With growing interest, Curtis put together a group of more than 100 of his finest prints and over the next several years they traveled to different museums across the country. By 1907, Ella McBride had been hired to manage Curtis's studio and with her commanding personality, became an important and dependable assistant. She lived with his family and was entrusted with the operation of his booth at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in 1909.

In 1911 Curtis created a live stage production titled The Indian Picture Opera or Picture Musicales that consisted of him lecturing accompanied by colored lanternslides and music. The show was critically successful and even included performances at Carnegie Hall and the Brooklyn Institute, but the high cost of production negated the original fundraising intention of the event. This multi-media extravaganza led to his first venture into motion pictures. With the assistance of the young Edmund Schwinke and others, the resulting film titled In the Land of the Headhunters (later renamed In the Land of the War Canoes) debuted in 1914.

The film opened first in New York and later at the Moore Theater in Seattle. Although it attained great critical acclaim, it never received the commercial success Curtis had hoped for.

Beginning in February 1912, the Washington State Art Association sponsored a display of photographic art in their downtown galleries. This organization was the first attempt at a public museum in Seattle. Its photography exhibition consisted of works by the leading commercial studios of the period. Besides Curtis, other established locals included Webster & Stevens, Nowell & Rognon, James & Bushnell, and several others.

The highlight of the show was a selection of gravures from The North American Indian, which was purchased for the Association by a local collector. With his estranged brother Asahel serving as the first curator of photographic art for the association, they sponsored a second exhibition the following year in January. This time Curtis exhibited five portraits and two artistic studies; “Lunette, The Hopes of Youth” and “Decoration, “Ambitions of Youth.” The works were conceived as mural designs and “evolved by A. S. Muhr.” indicating the importance of their collaboration. Muhr died that same year, leaving a large gap in Curtis’s production. The following year, his major benefactor, J. P. Morgan, also passed away, but fortunately the philanthropist’s son and family continued to offer their patronage.

New Processes, Changing Times

By 1916, Curtis’s studio began production of the “Orotone” or goldtone process. With the images printed on glass backed with a gold metallic finish, the resulting effect attained a unique and beautifully radiant product that had tremendous commercial appeal. Due to the constant financial stress and coupled with Curtis's lengthy excursions, his wife, Clara, divorced him and was awarded ownership of both their home and the studio.

With increasing financial and emotional difficulties, Curtis and his daughter Beth relocated to Los Angeles and opened a new studio in the Biltmore Hotel. Attempting to continue his work with Native American subjects, he soon found that the southwestern reservations were rapidly changing from the encroachment of non-native religious organizations and the natural advancement of progress. Undaunted, he continued his production but with a renewed sensitivity to the heinous treatment that the indigenous culture had endured in California.

By 1923, Curtis began an association with Hollywood film director Cecil B. DeMille who utilized his talents as a cameraman and still photographer. Although the employment offered some financial relief, within five years he was forced to exchange copyright ownership for the North American Indian to J. P. Morgan’s company in order to procure the funding to complete the final three volumes. Besides relinquishing these copyrights, in 1928, he sold the master print and negative for In the Land of the Headhunters to the American Museum of Natural History.

Given the increasing decimation of Indian cultures, Curtis was reinvigorated after discovering that the perceived traditions that he cherished were still relatively intact in Alaska. He completed the necessary material for the final volume of the North American Indian and returned to Seattle en route to Los Angeles. However, his ex-wife's animosities had not subsided and she had him arrested for deferred alimony and child support payments that were later dismissed by the court.

At the beginning of the Great Depression, Curtis finished the final two volumes of The North American Indian published in 1930. Only 272 sets had been printed over the 30 years the project had taken to complete. This was followed by a period of illness and stress related health concerns that subsided slightly when he began to follow a growing interest in gold mining. Although this pursuit was never monetarily rewarding, he kept chasing the idea of financial security that always seemed to elude him.

In 1936, Curtis resumed another employment opportunity with DeMille in Hollywood and began working on his memoirs, which unfortunately, never found a publisher. He spent his final years surrounded by his daughters in California. Edward Curtis died on October 19, 1952.

Culture and Cultural Questions

In the early 1970s, a revival of interest in Curtis’ work began after a large collection of his printing plates, photographic prints and glass plate negatives were located along with 19 complete sets of The North American Indian. The cache had been stored in Boston, at the Charles E. Lauriat Company, which had purchased the collection in 1935 from the Morgan Company.

Around the same time, Bill Holm and George Quimby of the Burke Museum at the University of Washington located and restored the single extant print of Curtis's 1914 film, In The Land of the Headhunters. In 1972 they added a new score and renamed the movie In The Land of the War Canoes.

Although interest began to increase for Curtis’ groundbreaking work, a series of criticisms also began to surface. Curtis and his work were accused of presenting a false and inaccurate account of Native American culture by using stereotypical conventions and staged scenarios to fit his own interpretations of an implied civilization on the brink of obscurity. In his defense, most artists of Curtis’s period whether in paintings, photography, and even motion pictures, all shared the same romanticized notions of Native Americans that reflected the misinformed consensus of the time, well meaning or otherwise.

Curtis’ genuine concern and admiration for Native Americans was reflected in his personal life as well. In 1924, he assisted in the formation of the Indian Welfare League, which lobbied for the political and social causes of Native Americans contributing to the ensuing Indian Citizen Act (The Snyder Act) giving indigenous people among other things, the right to vote.

Legacies

There are several important public collections of Edward Curtis's work. The Library of Congress holds more than 2,400 of his original prints and the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, has the entire 110 master prints assembled by Curtis for his early traveling exhibition of the North American Indian, begun in 1905. In Seattle, the University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections and Manuscripts Division contains a significant amount of Curtis material. The Rainier Club whose membership included Curtis, also has a small but choice collection of his earlier works.