The Alaska-Yukon-Pacific (A-Y-P) Exposition was held in Seattle at the University of Washington campus from June 1 to October 16, 1909. Planning for its extensive landscaped grounds and many buildings began several years before opening day. In October 1906, the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition Company hired landscape architect John C. Olmsted (1852-1920) of the prestigious Olmsted Brothers firm of Brookline, Massachusetts, to design the grounds. The A-Y-P Exposition Company leased the southern portion of campus where the forest had been cut over once, but where second-growth trees and dense underbrush covered the slope from about 41st Street to the lakeshore. Olmsted developed a plan that would serve the needs of the fair as well as those of the university after the exposition ended. His plan differed from other world's fair plans in that it relied on the natural scenery, including Mount Rainier and Lake Washington and Lake Union, for focal points around which he laid out the buildings, roads, and paths. By the time of the fair's opening in 1909, gardeners had transformed the forest into a park with avenues, paths, cascading water emptying into the Geyser Basin (now Drumheller Fountain), buildings, and beautiful vistas looking out onto Seattle's distinctive natural surroundings. A hundred years later, elements of the Olmsted design remain as legacies of the exposition.

The Fair and the Olmsteds

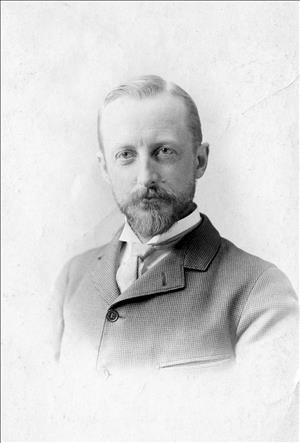

The Olmsted Brothers firm was an obvious choice for designing the exposition grounds. The preeminent landscape architecture firm in the United States, the Olmsted family firms had designed two other world's fairs, the World's Columbian Exposition at Chicago in 1893 and Portland's Lewis and Clark Exposition in 1905. Also, John C. Olmsted had worked in Seattle before, preparing a city-wide parks plan in 1903 and a plan for the university campus in 1904.

Olmsted came to Seattle in late 1906 at the urgent request of the A-Y-P Exposition Company Board of Trustees in October 1906 to develop a plan for the exposition. The exposition company had leased the lower part of campus, below 41st Street, which the university was not yet using. He described the area in a letter to his wife:

"The growth on the ground is so dense I could not see much. The land has never been cleaned up. Most of the original timber was cut and there were fires but there are still some groves and scattering original fir trees left. I suppose they were thought too small or of inferior quality to cut at the time lumbering was done but there are still trees 3’ to 4 ft diameter and a few even larger perhaps. What remain look like the very biggest we ever had in Maine. They are tall and straight & would make fine masts. A dense growth covers the ground, sometimes mostly young fir trees, sometimes alder trees, maples and others. The alders are pretty trees & I saw some near the boat house with tall straight smooth trunks like forest beech trees about 16 or 18 inches diameter. The undergrowth is extremely dense. The climate is so damp that everything grows luxuriantly. Brake ferns are higher than my head. The Sallal [sic] rattles like starched linen when one walks through it ... . I followed trails mostly but where I didn’t it was hard getting through. Occasional partly burnt logs impede one" (John C. Olmsted to Sophie Olmsted, October 20, 1906).

The campus lay some distance from the more developed parts of Seattle. The Brooklyn neighborhood, as the University District was then known, had a business district and several platted additions, but only one streetcar line served the area and only one road -- via the Latona Bridge, where the Interstate 5 bridge is today -- connected the neighborhood with downtown. After visiting the campus in 1908 with his colleague James Frederick Dawson (1874-1941), Olmsted described walking south through the woods to 19th Avenue and Galer Street, just east of Volunteer Park.

In creating his plan, Olmsted had to work within two significant constraints. First, he had a budget of $350,000. This had to cover clearing about 200 acres, grading the slopes, and planting the grounds. Second, the grounds and four of the buildings would be used by the university after the A-Y-P. The state legislature funded the Fine Arts Building (now Architecture Hall), and the Auditorium, Administration, and Mechanical Engineering buildings as permanent buildings for later use by the school. University officials requested that they be located on the northern end of campus, near the existing university buildings.

Styles, Designs, and Costs

Having been hired before the architects, Olmsted proposed a building style for the exposition. He recommended an "ancient Russian" style, in honor of their early colonization of Alaska and also because the spires characteristic of that style were “particularly well adapted to the varied sky line which we advocated as being needed to harmonize with the surrounding evergreen forest” (Olmsted to Smith).

When John Galen Howard (1864-1931) of Howard & Galloway, the supervising architects of the exposition, first considered the Russian style, he suggested that because of the number of architects working on the project who had not previously collaborated, the style may be too unfamiliar to remain coherent across the buildings. Howard and the other architects who worked on the larger buildings primarily chose neoclassical style, in keeping with other expositions of the era.

Olmsted produced a preliminary plan in November 1906. Exposition company officials in charge of different areas of the fair had given Olmsted the specifications for the space they would need. This first plan incorporated all of the requests, which pushed the grounds out beyond the Northern Pacific Railroad tracks that looped through the lower section of campus (where the Burke Gilman Trail runs today). The cost exceeded the budget and Olmsted went back to the plans to tighten them up and place the majority of the grounds within the railroad loop. This saved on road building costs, as well as grading and planting costs.

Borrowed Landscapes

Using a concept called "borrowed landscape," Olmsted incorporated elements of the natural environment into his design to enhance the scenic beauty of the exposition. The Lake Union, Lake Washington, and Mount Rainier vistas created axes that organized the grounds around the views. The lake vistas are today obscured by buildings and trees, but the Rainier Vista remains one of the most recognizable and appreciated elements of the campus. As Olmsted wrote in an article in The Seattle Mail and Herald, "The magnificent views ... will, however, be by far the greatest features of the exposition and will be vividly remembered by most visitors when the best efforts of architects and landscape gardeners have been forgotten" ("Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition").

In addition to the vistas, Olmsted laid out the buildings around several circles. The largest, the Court of Honor, surrounded the Cascades and Geyser Basin (which survives today as Drumheller Fountain), beyond which lay the Rainier Vista. Formal avenues laid out in straight lines connected the circles. One avenue, Pacific Avenue (now the lower portion of Stevens Way) curved across the lower portion of the grounds, connecting Klondike Circle with Nome Circle via several smaller circles.

Olmsted reserved the southeastern corner of the grounds for a park. There the gardeners tidied up the original forest, planted native flowers along five miles of trails, and placed rustic benches throughout. James Frederick Dawson, the site supervisor, described their efforts: "All the dead trees, which were not attractive-looking, and all the debris throughout the entire woods were cleaned out, and trails from six feet to eight feet wide were built" (Dawson, 39). Olmsted envisioned this as a place for respite from the crowds and excitement of the exhibit buildings and the Pay Streak.

After several modifications tightening up the plan by making the buildings closer together and reducing the garden spaces, Olmsted completed the final plan in May 1907. On May 17th, he met with the university's Board of Regents for their approval of the plan.

Clearing and Planting

Grading work commenced as soon as the regents accepted the plan. In order to shape the grounds according to Olmsted's plan, about 200 acres had to be cleared of trees and brush. Loggers had cleared the old-growth forest some years before but a well-established second-growth had filled the area. Grading required dynamite and teams of horses pulling plows across the hill. The hardpan in some areas proved so difficult to cut through that the crews kept a blacksmith on hand to sharpen the plow blades regularly. Crews removed thousands of cubic yards of dirt to make room for the buildings and to prepare road beds.

Creating the amphitheatre required no earth moving. Where Padelford Hall and its parking garage are located today, the hill curved, forming an ideal seating area for performances and speeches. Grounds crews had only to add seats.

In early 1907, gardeners laid out 20 acres for a nursery at the south end of the campus. They built a 100-foot-by-30-foot greenhouse for tender plants. Hardy plants and sod went into the ground outdoors. They grew plants from a wide variety of sources. They bought seed, primarily for flowering annuals. They also bought railroad car loads of evergreen perennials. A number of trees and shrubs, such as Douglas fir, rhododendron, and evergreen huckleberry, they moved from other parts of the campus during the clearing process. Thousands of plants came to the exposition on loan from nurseries on the East Coast, including rhododendrons, dahlias, and gladiolus. To stretch the landscaping budget further, gardeners propagated thousands of perennials from cuttings.

The design called for a range of styles, from formal gardens to idealized forest. Close to the buildings, the plantings tended to be less formal, with a number of native plants emphasized. Closer to the avenues and pathways, formal plantings predominated, with an emphasis on non-native annual flowers. Masses of roses and manicured hedges filled the formal garden laid out below the Geyser Basin.

In an article about the plantings at the A-Y-P, Dawson explained a difference between the A-Y-P and other world's fairs of that era. Olmsted did not call for any "gaudy displays of ornamental carpet-bedding, such as designs of emblems, mottoes, or names of buildings worked up in colored foliage plants," because he wanted the beds to be, "simple and harmonious with the magnificent natural surroundings" (Dawson, 34).

Dahlias, Geraniums, and Rhododendrons

The official flower of the A-Y-P, the cactus dahlia, filled beds along the Lake Union and Lake Washington vistas, as well in other plantings around the grounds. A committee had chosen the cactus dahlia for its long blooming season and its recent introduction into Northwest gardens. They hoped Seattleites would embrace the flower and establish a cactus dahlia festival akin to Portland's Rose Festival. Although dahlias remain popular in Seattle gardens, no groundswell ever emerged in support of a Dahlia Festival.

At the main entrance to the exposition, at 41st Street and 15th Avenue, tens of thousands of salmon-pink geraniums bloomed in a mass of color. To acquire enough starts to populate the beds of geraniums here and along the Pay Streak, the exposition officials named November 14, 1908, "Geranium Day" and asked Seattleites to bring plants to donate to the fair. Each donated plant entitled the bearer to free entrance to the grounds (although the fair was not yet open, visitors had to pay to enter and observe the progress).

As with many of his designs, Olmsted included a significant number of native plants in his plans. While working on another project in the Seattle area, he marveled, "the men detest everything wild except the big leaved maple trees and madronas. Bushes are to them merely weeds to be trampled down and destroyed so grass can be sown. It seems especially queer that they cannot appreciate the beautiful evergreen undergrowth they have here -- the Oregon grape, the Sallal (sic) and the evergreen huckleberry" (Olmsted letter, May 28, 1908). Rhododendrons, which Olmsted valued more for their foliage than their blossoms, flanked the large buildings of the Court of Honor. Other native shrubs filled beds around building foundations. Groves of trees dotted the landscape, and Douglas firs framed the lake vistas.

Although the exposition grounds differed significantly in purpose from other Olmsted parks in Seattle, the design principles generally seen in those parks apply to the A-Y-P design. Incorporating the surrounding landscape; adapting the plan to the topography; curving, meandering paths in the less formal areas; using native vegetation; and water features are all characteristic of Olmsted design.

Not all of Olmsted's ideas made it into the final design. He had hoped to build an "intramural electric railway" to transport people around the grounds on an elevated track. Instead, the fair featured rickshaws that could be rented, and these provided summer jobs for a number of college students.

James Dawson's Role

Olmsted visited the campus a number of times during the planning and early stages of construction. After November 1907, James Dawson, his colleague from Olmsted Brothers, took over the implementation of the plan. He stayed in Seattle much of the time and supervised the gardening crews. Dawson directed the planting of more than two million trees, shrubs, and flowering plants; path and avenue construction; lawn seeding and sod installation; and the preparation of the forested park. Dawson would return to work in Seattle on private projects and public parks after the exposition. In the 1930s he would design the Washington Park Arboretum.

After the fair, the exposition company demolished the temporary buildings that could not be adapted for use by the university. Parts of the A-Y-P grounds remain intact and others have disappeared over time. Nome Circle (near where the Husky Union Building is now) and Klondike Circle (just southeast of Architecture Hall) were visible in an aerial photo from the 1920s. The lower portion of Stevens Way largely follows the path the A-Y-P's Pacific Avenue and many other paths continue on the lines of the Olmsted plan. The Geyser Basin remains a central feature of the campus today, now known as Drumheller Fountain. Rainier Vista remains with its spectacular view of the mountain as the defining element of the University campus.

Seattle's Olmsted Parks and Boulevards

Olmsted included the campus in his 1903 plan for Seattle's park system. Designing the A-Y-P provided an opportunity to shape the campus' future design. His suggestion that a chain of boulevards connect the city's large park also took a step forward with the A-Y-P. The Board of Park Commissioners completed the University Extension, a boulevard that connected the campus with Lake Washington Boulevard on the south side of what was then the Montlake Portage (it is now the Lake Washington Ship Canal). A writer in Alaska-Yukon Magazine praised the boulevard running from Mount Baker Park to the university for its beauty and noted, "Probably nothing will advertise Seattle more than this driveway" (Hoag, 362).

In 1911 the university's Board of Regents asked the Olmsted Brothers to create a new plan for future growth at the university. They did not hire the firm to carry out the plan, but some of its components were implemented by Bebb & Gould, a local architecture firm that created the next campus plan in 1915. Carl F. Gould (1873-1939) incorporated Olmsted's recommendations for collegiate Gothic architectural style and placing a library at the center of the campus.

The A-Y-P landscape served the University of Washington by clearing the forest. Beyond that, the exposition gave the university a plan for future development that proved so well-designed that a number of its features remain today.