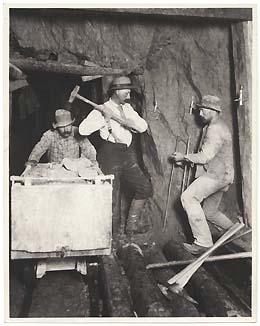

The Spokane Stock Exchange operated from 1897 until 1991. It was one of about 200 regional exchanges initially trading in mining shares issued as penny stocks (shares selling below a dollar). Spokane, the railroad and commercial center of the "Inland Empire," was already the corporate headquarters for most of the gold, silver, lead, and zinc mines of the region. Thus it was the logical location for such an exchange. At its peak of operation, the Spokane Stock Exchange rivaled the mining exchanges of San Francisco, Denver, Salt Lake City, and Toronto. While other stock exchanges adopted new technologies, the Spokane Stock Exchange continued to post transactions on a chalkboard. Trading swung from brisk to so desultory that from time to time the exchange closed. Although the exchange occupied several buildings over the years (including 725 W Sprague for 40 years, and three different locations on Riverside) it was always situated so that observers could watch its quotations being posted. Such transparency, though, did not extend to after-hours backroom trading, and with the introduction of state and federal regulation, its activities come increasingly under the scrutiny of the Securities and Exchange Commission. The Spokane Stock Exchange crashed along with others in 1929, recovered after World War II, and enjoyed an expansion with the silver boom of the 1960s. Its downfall began in the 1980s when the admission of a particularly shady operator reawakened the attention of the SEC, which threatened punitive action. Broker loyalty vanished, and the Spokane Stock Exchange closed on May 24, 1991, the last regional mining exchange in the United States.

A Market for Mining Shares

Although mining companies needed to sell shares in order to raise capital, they were not altogether happy when stockbrokers got into the act, complaining that published quotations decreased the actual value of the stock. Clergy and reformist politicians also opposed mining exchanges as nothing more than gambling operations. They especially decried the practice of enticing naive farmers to part with their hard-earned profits right after selling a crop, using the money that normally would have paid off crop loans and mortgages. Spokane merchants, however, liked the stock exchange because it brought people and their money into the city.

Beginning in 1890, there were several meetings of Spokane businessmen with mining interests. Particularly active and influential was a group dubbed “The Sacred Twenty,” who wanted to start an exchange that would “provide an orderly market for mining shares, determine qualifications for Exchange membership, and define the responsibility of brokers toward their clients” (Bolker, 3). After several false starts, this group merged with a rival would-be exchange, and the Spokane Stock Exchange opened on January 18, 1897. It consisted of 32 members and listed 37 stocks of mines in southern British Columbia, northern Idaho’s “Silver Valley” in the Coeur d’Alene Mining District, and Northeastern Washington. As a later writer summarized them, their rules:

“laid stiff discipline on the free wheeling traders. The open call system was accepted by all. Brokerage charges were set at uniform commission rates instead of being arbitrarily set by individual brokers. Mine owners whose properties were listed on the exchange were required to issue a sworn statement regarding the condition of their property, and the Directors defined strict financial requirements for any issue submitted for listing” (Bolker, 3).

By 1900, the silver/lead output of the Coeur d’Alene Mining District was $10 million dollars, and there were 534 principal mining claims operating. Many of these, of course, were traded on the Spokane Stock Exchange. The 1900 Spokane City Directory listed 55 mining brokers. During its earliest years, the stock exchange moved from one building to another, but from 1918 to 1927, it rented space on the ground floor (later the first floor) of the Paulsen Building, 400 block on Riverside, one of Spokane’s most prestigious business locations.

Unregulated Dealings

The Spokane Stock Exchange began in a totally unregulated era. Practices illegal today, such as insider trading, were once fairly routine. Because of the persistence of questionable dealings, there were efforts in many states to regulate stock markets. Washington’s legislature failed repeatedly to do so until, in 1923, it enacted a securities regulation but, oddly, exempted mining corporations. On the national level, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was not established until 1934. Among Spokane’s many ethical stockbrokers were some bad apples, and the Spokane Stock Exchange was often in SEC sights.

The Spokane Stock Exchange flourished during the generally heady 1920s, but crashed along with everything else in 1929. Gradually, during the 1930s, its fortunes crept back up, especially with the passage of the Silver Purchase Act of 1934, which authorized federal purchase of newly mined silver at a fixed price.

Change in the Exchange

For a number of years, beginning in the 1920s, the Spokane Stock Exchange was called the Standard Stock Exchange of Spokane. From 1929 to 1971 it was located at 725 W Sprague, the former Eilers Building, which was renamed the Standard Stock Exchange Building, then later the Radio Central Building. Sam J. Wilson, who had been refused a seat on the Spokane Stock Exchange, organized his own exchange, taking a number of members of the Spokane Stock Exchange with him. The original exchange continued in a moribund condition until in 1946, the board of Standard bought all remaining shares of the old Spokane Stock Exchange and re-adopted its name. During the Standard years, the SEC objected to the “casual bargaining in unlisted stocks, called over-the-counter (OTC)” and the Spokane brokers who “customarily retired to a room off the trading floor to deal cozily by themselves in OTC shares” (Fahey, 118). During the 1930s, the Standard Exchange had to tighten its regulations nine times to meet federal requirements and reassure its customers.

The post-World War II period saw not only restoration of its original name, but the admission to the trading floor of additional mining entrepreneurs, including Benjamin A. Harrison (d. 1993) and Harry F. Magnuson (1923-2009). These two were able to take advantage of the silver boom of the 1960s, during which the average penny stock appreciated 160 times. Participation in the Spokane Stock Exchange was vast, with more than 100,000 investors from all 50 states and many foreign countries. Barron's declared “Speculators in silver stocks have struck it rich in Spokane,” and the Seattle Post Intelligencer called Spokane “the speculative darling of the industry” (Fahey, 121). Harrison’s obituary describes him as “president of the Spokane Stock Exchange for 12 years ... and its most knowledgeable mining stock broker. ... The mining stocks Mr. Harrison traded brought immense wealth to northeastern Washington and northern Idaho” (The Seattle Times).

Scandals and Stock Manipulations

However, the apparent insider trading and stock manipulation by Harrison and Magnuson again attracted the scrutiny of the SEC. These two were not the only traders called into question. Alleging that 11 of the 13 new member brokerages published fraudulent OTC quotations, the SEC sought federal injunctions to halt the practice. Magnuson died on January 24, 2009, having long since become a respected and philanthropic resident of the Silver Valley. A front-page article in the Spokesman-Review stated: “Harry Magnuson was a legend in North Idaho and Spokane, where his financial support and tenacity preserved the Cataldo Mission, kept the interstate freeway from running through downtown Wallace, and helped save Gonzaga University from financial collapse” (Boggs, 1). Another 1960s scandal involved the Cleek-Tindall Company, which traded in uranium stocks. The SEC accused it of having rigged stocks and made false statements during the 1950s concerning the value of uranium on mines it represented. Upon the recommendation of the SEC, the board expelled the company from the Spokane Stock Exchange.

Although the 1960s saw a revival of the Spokane Stock Exchange, historian John Fahey saw it as “fusty indeed” and quoted a July 1968

Barron’s

article to illustrate the point:“Each day at about 10:30, local residents on their coffee breaks … make their way into a small rectangular room to watch the action. … They stand, sit or shuffle about behind a wooden rail that separates them from floor traders. Occasionally they shout orders to brokers across the rail. The Spokane Exchange is the only one in the nation that allows open trading. … To the casual visitor … the tough job is to distinguish the millionaires from the dreamers” (Fahey, 120).

During the 1970s, the brothers Nelson Bunker Hunt (b. 1926) and William Herbert Hunt, sons of a Dallas oil tycoon, became principal owners of the Sunshine Mine in the Coeur d’Alene Mining District and, along with some wealthy Arabs, “gobbled futures, imagining they might corner the silver market. Silver trading sped from a trot to a gallop” (Fahey, 122). All of this dizzy speculation, combined with changed trading rules for metals and the intervention of the Federal Reserve, ended the silver bubble in 1980. Prices bottomed on March 27, which was also “Bloody Thursday” on the New York Stock Exchange.

The Last of its Kind

On September 17, 1985, the Spokane Stock Exchange tried to recover its integrity and viability when younger members voted out the old board of governors, including Harrison. They wanted to move toward an electronic trading system (that never materialized) and to expand their coverage to include more than just mining stocks. Of the few remaining registered regional mining exchanges in the United States, it was by then the largest, and the only one at which spectators could still call out orders directly to brokers on the floor and watch them being transacted. From 1972 to 1987 the home of the Spokane Stock Exchange was the second floor of the Peyton Building, 700 block of Riverside, another prestigious business location.

Just as the exchange seemed to be recovering, its board made the fatal mistake of granting a seat on the exchange to Meyer Blinder (1921-2004) of the Blinder, Robinson and Company of Englewood, Colorado. The Spokane brokers were apparently dazzled by Blinder’s ability, as hinted to a reporter, to provide Spokane with an electronic dissemination of quotes. The board was unaware of, or chose to ignore, Blinder’s long history of SEC violations and his reputation as a sleazy telemarketer who used high-pressure tactics to peddle worthless stocks. Soon after assuming his seat on the Spokane exchange, Blinder was indicted on racketeering and securities fraud charges, later convicted, and spent more than 40 months in federal prison.

The Spokane Stock Exchange spent its few remaining years at 601 W Riverside, Room 200, still in the heart of downtown. As the SEC continued its pressure, brokers began deserting. Its remaining dispirited members voted to dissolve the exchange, and its last trading day was May 24, 1991. Although once one of the great regional mining exchanges and the last of its kind, upon its demise, the Wall Street Journal described the Spokane Stock Exchange as “the victim of painfully paltry trading and horse-and-buggy era technology” (Fahey, 124).