In 1878, Layfayette Stevens discovers coal in the foothills northeast of Sedro, at a place later called Cokedale (in Skagit County). This joins earlier nearby strikes to produce coal fever in the region, which is amplified by prospects of a railroad to connect the town of Sedro with Fairhaven, on Bellingham Bay, and by further prospects of a route over the Cascade Mountains via Cascade Pass for James J. Hill's (1838-1916) transcontinental Great Northern Railway. Fifty coke ovens will be built at Cokedale and the Fairhaven & Southern Railway (completed 1889) will transport coal from Sedro to the bay. Cokedale will be a good producer for more than a dozen years. Eventually the coal boom will turn bust, but Sedro will merge with its neighbor Woolley to form Sedro-Woolley in 1898, and will live beyond the coal boom to grow steadily after 1900.

Coal, Not Gold

When prospector Lafayette Stevens discovered coal in 1878, northeast of what would become the town of Sedro in 1885, he had been searching for elusive placer gold in the creeks of the upper Skagit River region. Instead, he and partners promoted what they called the Crystal Mine as a coal producer -- an area that would later be called Cokedale. In 1880, an immigrant publication explained that both the Crystal Mine and other nearby coal strikes were part of a chain of coal seams that stretched from Nanaimo on Vancouver Island to the Skagit River and from King County to Coos Bay.

Skagit was one of three Washington counties that figured into the coal boom of the 1870s-1890s, a boom that boosted the towns of Hamilton and Sedro, a dozen miles apart on the Skagit River. The Hamilton discovery almost ended before it began. In September 1873, when Amasa Everett, Lafayette Stevens, and Orlando Graham heard of Indians stories about black rock that burned, they climbed what became known as Coal Mountain on the south shore of the Skagit River, across from the Hamilton townsite. They found coal, but a boulder rolled down the steep flank and mangled Everett's lower right leg, leading to his forever-after nickname, Peg-leg.

Coal was in great demand, especially in San Francisco, for heating of homes and businesses, for steamship fuel, and increasingly for railroads as they built up and down the coast after the mid-1860s. But at the Crystal Mine strike near Sedro, Stevens lacked sufficient capital to sink the necessary deep shafts, much less the required timbering. So he sold his coal interests to a financier, A. E. Barthwick, in 1887, a year too early as it turned out -- coal and railroad fever was about to break out.

Coal and Railroad Fever

In 1888, the Oregon Improvement Company sent geologists to the Skagit region, and over the next few years the company bought more than 1,500 acres of potential mining property along the upper Skagit River. Soon thereafter, developer Nelson Bennett (1843-1913) made the towns of Fairhaven and Sedro an offer they couldn't refuse. Awash in cash after he and his brother built the Stampede Pass tunnel for the Northern Pacific Railroad through the North Cascades, Bennett proposed to connect the two towns by rail, delivering Skagit coal to Bellingham Bay. All he needed was the respective boosters to pledge significant portions of their townsites.

Fairhaven townspeople had been frustrated for nearly three years, waiting for other rail interests to make a move, and Mortimer Cook (1826-1899), founder of Sedro, was ecstatic at the prospect of the first railroad north of Seattle running through Sedro. The deal was soon struck. In December 1888, Bennett formed the Fairhaven Land Company, and the two towns set a deadline -- Bennett would take a year to build a working railroad that would connect with James J. Hill's Great Northern line, which was then building across the Rocky Mountains on its way to Washington.

On Christmas Eve 1889, the first passenger train of the Fairhaven & Southern Railway made a trip from Fairhaven to Sedro (since merged with the town of Woolley in 1898), and the boom revved into high gear. In the fall of 1891, Bennett completed his railroad by building from Sedro-Woolley northeast to the coal mines, which would soon be named Cokedale. He enlisted the financial help of C. X. Larrabee (1843-1914), who had made a fortune in silver at Butte, Montana, in the 1870s and 1880s.

Cokedale's Rise and Fall

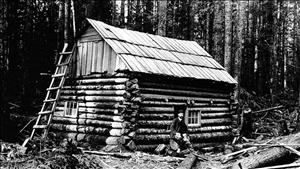

The name "Cokedale" came about after the coal was analyzed and found to be ideal for steel smelters that used coke as a catalyst during the Bessemer steel-making process. As in the eastern King County town of Wilkeson, brick "beehive" ovens were built to process the coke -- 50 at Cokedale and twice that number at Wilkeson.

Although the Cokedale ovens produced coke for another dozen years at a pretty good clip, the Fairhaven & Southern Railway was short-lived. Bennett and Larrabee sold both the railroad and the mines to Hill, who rejected a Cascade Pass route for his transcontinental Great Northern Railway and chose a Stevens Pass crossing instead, farther south.

The entire region soon fell into economic chaos as the nationwide financial panic set in during the 1890s. Fairhaven effectively became a ghost town by the early twentieth century, but Sedro-Woolley lived beyond its infancy, having added agriculture and logging to its economic mix. The town grew steadily after 1900.