Washington's first World's Fair -- the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition -- was held in Seattle on the grounds of the University of Washington campus between June 1 and October 16, 1909, and drew more than three million people. The Pay Streak was the A-Y-P Exposition's midway area. It offered (for a price) a dizzying array of carnival rides, souvenirs, refreshments, and quasi-educational exhibits. These last involved the display of human beings in varying degrees of their (purported) natural settings, going about what was supposedly their usual daily work. The Baby Incubator Exhibit, which introduced fairgoers to an early version of mechanical controlled environments for the benefit of premature infants, featured living human babies as the (passive) performers, demonstrating applied science in the nursery decades before such technology was commonly integrated into neonatal care in hospitals.

Preemies on the Midway

Baby incubator exhibits were an expected feature on exposition midways from the 1896 Berlin Exposition on. Visitors to Omaha's Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition in 1898, Buffalo's Pan-American Exposition in 1901, St. Louis's Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904, and Portland's Lewis and Clark Exposition in 1905 experienced a similar concession. (At most of these, including the Lewis and Clark Exposition, the Baby Incubator Exhibit was managed by Dr. Martin Couney, the foremost promoter of the baby incubator sideshows at expositions. Couney's Baby Incubator Exhibit at Luna Park in New York's Coney Island ran from 1903 to 1943. Although A-Y-P's Baby Incubator Exhibit bears a strikingly similar physical resemblance to Couney's baby incubator shows, no connection between Couney and the A-Y-P has yet been discovered.)

As announced in The Seattle Daily Times on February 14, 1909, "The baby incubators will be seen at The Exposition, as well as W. H. Barnes with Princess Trixie, the educated horse." The display of human infants on the Pay Streak midway apparently elicited no protest from fairgoers (including visiting physicians), or from the local medical community.

Seattle already had a permanent (or at least seasonal) baby incubator exhibit: the Infant Electrobator concession at Luna Park in West Seattle. (An electrobator was an incubator heated by electricity.) Further details about this concession, where infants must have been rattled by the clatter of the wooden roller coaster and soothed by calliope music from the nearby carousel, appear to have vanished. It is possible that the A-Y-P exhibit and that at Luna Park were in some way connected.

French physician Alexandre Lion's incubator, patented in 1889, was commonly used in baby incubator exhibits at expositions. These incubators varied greatly from the infant incubators utilized in modern neonatal intensive care units. The A-Y-P's incubators regulated the temperature inside the unit and pulled in outside air for ventilation, nothing more. They would have been beneficial to well preemies needing no special care beyond steady warmth. The incubators exhibited at fairs and expositions had no ability to aid babies who could not breathe on their own, and there was at the time (and for many subsequent decades) no therapy for such children.

The A-Y-P Baby Incubator Exhibit apparently experienced no deaths, and it is unlikely that babies who lacked a very good prognosis would have been put on display for fear of negative public relations should they not survive, if for no other reason. By comparison, during the course of the A-Y-P the Seattle Department of Health attributed 33 deaths throughout the city to premature birth, among 64 deaths attributed to that cause during the year 1909. Luck was also with the A-Y-P in that the incubator babies were spared the fate of those exhibited on the Pike at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, where an epidemic of contagious diarrhea among the infants cost the lives of nearly half.

M. E. Fischer -- Physician, Salesman, or Concessionaire?

The Baby Incubator Exhibit was among the earliest concessions secured for the Pay Streak. The April 1908 Alaska-Yukon Magazine included it on a list of concessions "already signed," along with the Eskimo Village and Frank H. Nowell's appointment as official A-Y-P photographer. "Kny-Scherrer [sic] Company, New York," was credited as signatory on the contract. Kny-Scheerer was a surgical supply company with an office in Jamaica, New York, that manufactured the Lion-style baby incubator.

The manager of the A-Y-P Baby Incubator Exhibit was M. E. Fischer. An M. Edward Fischer, his wife Laura, and son Henry were enumerated in the 1910 Federal Census at 4312 10th Avenue NE (now Roosevelt Way NE), several blocks away from the Pay Streak. Fischer's employer is listed as surgical instrument company. If this was indeed the M. E. Fischer in charge of the Baby Incubator Exhibit, he was still a local resident in 1920, when census takers enumerated him in Bellevue.

The Seattle Star (the city's most salacious daily at the time) called Fischer "the big-hearted and genial chap who stands in loco parentis to all of the world's little weaklings that are offered to him," and went on to claim that "he has had his incubators at every exposition since the incubator principle was tested and found good" (June 15, 1909). This claim was almost certainly refers to the incubators, not to Fischer, although it is possible that if he were a product salesman for Kny-Scheerer he was present at other expositions. Fischer is notably not referred to as a physician.

During this time period, the Infant Incubator Company at Dreamland, an amusement park at Coney Island in New York, advertised in The Billboard, the trade magazine for theatrical professionals including sideshow and midway performers: "Baby Incubators, complete installations as operated by us, for sale to hospitals and amusement parks" (May 1, 1909). The contact listed was Dr. S. Fischel, who was also in charge of the Dreamland incubator show in 1911 when that park suffered a devastating fire in which some of the babies were initially reported to have been killed. The similarity between the names of A-Y-P's Fischer and Dreamland's Fischel seems coincidental, but remains intriguing.

The Baby Incubator Exhibit attendants were advertised as medical professionals, and perhaps they were. "We save the lives of babes ... . Leading children's physicians, highly trained nurses -- every modern surgical appliance and medical appliance constantly at hand," trumpeted the display ad in The Seattle Star (June 6, 1909, p. 5).

Peddling the Preemies

Like the Igorrote Village and Eskimo Village concessions, the Baby Incubator exhibit received continual press during the fair. Most of this "news coverage" consisted of breathless reports on the progress of various babies, who were identified by first name. The babies were depicted as tiny feisty prizefighters who, aided by their incubators, could "fight (a bottle) not only often but for the full three-minute rounds" (The Seattle Star, June 15, 1909). The article concluded with a virtual step-right-up: "Daily, new little ones are coming into the incubators and with every one that comes there is a story of heart interest to stir the hardest."

By the middle of the exposition's run, newspaper readers were assumed to know the incubator babies by name and follow their stories. Under the heading "New Subject for Baby Incubator," The Seattle Daily Times reported, "The recent graduation of Catherine and the adoption of Dorothy have created no end of comment and discussion among the visitors ... . Little Tony will be ready for adoption when graduated from the incubator ... . Dorothy, the graduate, will spend the summer on a ranch near Rockford, with her adopted mother" (July 11, 1909). On August 15, 1909, the Times reported, "Little Guy, Fanny, Charles, Marguerite, Mabel, and Harry are now incubator subjects and are starting on a tiny path to life and success."

Paid display advertisements kept the babies' supposed struggle at the public forefront and emphasized the concession's potential to impart scientific information: "The fighting chance for babies. The Baby Incubators. The greatest heart interest exhibit at the A-Y-P. An education for mothers, a lesson for fathers. On the Pay Streak" ran an advertisement in The Seattle Daily Times on July 9, 1909. A June 10, 1909, advertisement in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer was more succinct: "We Save The Lives Of Babies." This ran directly under a larger advertisement for the Igorrote Village boasting "50 Head Hunters 50" -- the Pay Streak spectacles evidently spanned the gamut.

Life With Babies

The Pay Streak was often the busiest, loudest, most crowded portion of the exposition grounds. The Baby Incubator Exhibit, housed in a two-story neoclassical pavilion featuring Ionic columns and graced by ornamental pilasters and window moldings, was sited on the lower end of the South Pay Streak between the Temple of Palmistry and the Gold Camps of Alaska. The palmistry concession was probably a quiet neighbor, but the Gold Camps' raucous Wild West show and pan-for-gold activities must have detracted from the soothing nursery atmosphere cultivated in the incubator viewing room.

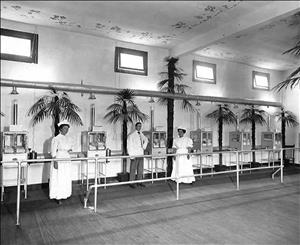

Fairgoers filed into this viewing room and examined Lion incubators arrayed against the wall. A rail separated patrons from the incubators (enclosed heated and ventilated glass boxes) in which the babies rested, cocooned in blankets. The Seattle Daily Times stated, "Some of the little ones are sleeping, some lying in almost inanimate positions, while others, who are making rapid progress in their development, cry and fidget just like healthy babies born at maturity" (August 8, 1909).

Female attendants wearing nurse uniforms and a male attendant in a white lab coat stood by. High transom windows admitted light and air. The ceiling was stenciled with an ivy design. Live potted palms were placed between the incubators, and weight-bearing support columns were designed to resemble palm trees. Fischer, and perhaps others, gave periodic lectures on incubator technology and other aspects of scientific infant care.

The exposition grounds closed to the public at midnight, but many people were present through the night: guards in the various buildings, firemen and Emergency Hospital staff, cleaning personnel, teamsters making deliveries, and many of the performers on the Pay Streak. This included the incubator babies and their caregivers, who almost certainly had bedrooms in the (non-public) upstairs area. Life with babies made (relatively) famous by virtue of their passive performance in the Incubator Exhibit still included the many mundane tasks of infant care: bathing, weighing, feeding, and changing diapers. A photograph showing the back side of the Baby Incubator Exhibit building documents an open porch area strung with a laundry line of diapers drying in the breeze.

It is difficult to gauge the actual size and age of the infants depicted in period photographs of the concession. One baby captured in a Frank Nowell photograph appears almost too large to be shoehorned into the incubator in which he sleeps (AYP536). An infant photographed in an open bassinette in the exam room also appears robust (AYP1212).

Images of incubator babies from other American expositions document infants of markedly smaller size than those captured in A-Y-P photographs. Larger babies would have presumably had a better chance of survival, although presumably very small infants would have impressed the crowds. If A-Y-P's incubator babies were larger than their preemie peers at other fairs, perhaps their rainbow ethnicity was their main draw.

Babies of All Nations

Much was made of the A-Y-P incubator babies' wide-ranging ethnicities. The Seattle Star called them "hustling little youngsters of every nation" and described "Peluck" (whom the paper identified as "a tiny little Siwash boy" from Kitsap County), "a blue-eyed little Swede girl," "little Oyusha San ... the daintiest little Japanese maid that was brought over from a strawberry ranch near Bellevue," and two-months-premature "Ralph ... with all an Irishman's fighting ability and the constitution of an Alaskan moose" (June 15, 1909).

By July 18, 1909, The Seattle Daily Times listed the "register of the Incubator Institute" as containing "American, English, Indian, Italian, Swedish, Syrian, and Russian (babies). A Japanese baby is daily expected." Exactly how this premature birth could be daily expected was not explained.

Later that month a much-publicized Children of All Nations Dinner was held in honor of the many children living and working on the Pay Streak. The Seattle Daily Times reported that "Siwash Jack, the Indian incubator baby, three months old, was brought to the table by his nurse" (July 24, 1909), begging the question of whether Jack needed the incubator or the Incubator Exhibit's ticket sales needed Jack.

On August 21, 1909, The Seattle Daily Times reported that Fischer's Baby Incubators was awarded third place, "most original," in the Parade of All Nations on Pay Streak Day.

Many of the Incubator Exhibit babies may have been foundlings, and at least some of these were touted to have been adopted during the course of the fair. Babies who were deemed large and strong enough by the staff transitioned to a regular nursery, then "graduated" and were moved to the exhibit's day nursery or left the exhibit, while other babies joined the concession to take their places. King County adoption records are private, making it difficult to determine the veracity of the "graduate" adoptions announced in the newspapers.

Although local newspapers carried no specific stories about non-foundling incubator babies, a July 4, 1909, article in The Seattle Daily Times states, "Little tiny mites are cared for in these machines until they become matured and physically strong enough to be returned to their parents."

The Baby Incubator Café

Photographic evidence of the Baby Incubator Exhibit's exterior clearly document a sign reading "café" on the side of the building. This feature appears to be unique to the A-Y-P concession: medical historians who have studied baby incubator shows from their inception have thus far uncovered no evidence of café features in incubator exhibits at any other exposition.

Although a period photograph of the concession captures a group of what appear to be waiters clustered outside the door marked "café," extensive research in A-Y-P Exposition archival materials has thus far not uncovered any menu for the Baby Incubator café, nor do period newspapers refer to the dining experience there, nor is the café mentioned in the Baby Incubator Exhibit's numerous display advertisements. This silence begs the question of whether food and drink were sold in the exhibit at all -- perhaps the term "café" was used tongue-in-cheek to indicate a viewing room where infants were fed by bottle? At many other expositions babies were breastfed by wet nurses in private spaces not on public view, also a probability for the Seattle babies due to the lack of effective artificial formulas at the time. If wet nurses were employed, they may have brought their own nursing infants along.

Sleight of (Tiny) Hand?

Another Baby Incubator Exhibit feature that was apparently unique to the A-Y-P was the option of hourly paid childcare. The Seattle Daily Times stated just before the exposition opened, "A nursery is conducted in connection with the baby incubator and infants may be checked at this place, where they will be in charge of competent nurses" (May 30, 1909, p. 3).

The presence of a café and the day-care service, as well as the apparently robust nature of infants who appear in period photographs, coupled with the extensive ballyhoo about their wide range of ethnicities, might mean that the A-Y-P Baby Incubator Exhibit leaned more toward money-making concession and less toward life-saving medical need. The public certainly saw, as promised in the electric sign across the top of the concession's facade, "Baby Incubators With Living Infants." Whether those infants chosen for display at the A-Y-P actually needed or derived any benefit from the scientific controlled environments in which they were displayed remains an open question.

The 1911 Secretary's Report of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition states that M. E. Fischer's Infant Incubator Exhibit generated $7,200 in Gross Receipts, providing an estimated $1,650 in A-Y-P revenue. At 25 cents per head, that would mean 28,800 tickets to the concession were sold. If indeed the "café" was an actual restaurant, however, some of these proceeds were likely generated by the sale of food and drink, and some portion of the proceeds were likely generated by the hourly child-care service.

From Sideshow to Hospital

Immediately after the A-Y-P's conclusion, Seattle Health Commissioner James Edward Crichton (1863-1933) approached the Seattle City Council finance committee to suggest that the city purchase one or more of the Baby Incubator Exhibit machines. "Health Commissioner J. E. Crichton believes that the City Emergency Hospital should be equipped with a baby incubator, such as was exhibited at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition ... Through the use of an incubator Dr. Crichton believes that the lives of many babies may be saved," reported The Seattle Times (October 20, 1909, p. 10). The 65-bed City Emergency Hospital shared Seattle's municipal building with city offices, the police department, and the city jail. Four beds were devoted to obstetrical cases. City Hospital treated emergencies and what were referred to as charity cases, i.e. the indigent.

The finance committee evidently agreed to fund the incubator purchase, obtaining a machine that was originally purchased for the fair but apparently kept as backup. The incubator was put to immediate use, as documented by The Seattle Times in a story that ran under the heading "City Hospital Takes Incubator Baby -- Equipment Stored at Exposition During Fair Period Transferred to Municipal Building": "Baby Stewart, born yesterday afternoon and weighing three pounds, was taken to the city emergency hospital this afternoon and placed in an incubator obtained from the exposition grounds, but unused during the fair period" (October 23, 1909, p. 14). The article mentioned that the incubator was obtained at a much lower rate than would have been possible on the open market.

Unlike the babies displayed at A-Y-P, Baby Stewart -- Bernard Stewart, son of George W. and M. Butler Stewart of Tacoma -- did not thrive. Born on October 22, 1909, while his parents were visiting Seattle, Bernard Stewart died at City Hospital on November 6, 1909, "after a patient and earnest struggle on the part of every nurse and every surgeon at the hospital to keep the child alive" ("Incubator Baby Dies").

Babies Today

By 1948 Providence Hospital in Seattle had five incubators with oxygen therapy (air that was conditioned with oxygen). Other Seattle hospitals with nurseries either had incubators by that time or introduced them shortly thereafter. Spokane's Deaconess, St. Luke's and Sacred Heart hospitals were also equipped with incubators by 1948.

By the early 1970s a growing number of Washington hospitals were equipped with newborn intensive care units that featured complex incubator technology approaching that found in current (2009) neonatal intensive care units.