On August 5, 1867, the Weekly Intelligencer, a precursor of the Post-Intelligencer, makes its debut in Seattle. The paper is the latest incarnation of what was originally called The Seattle Gazette, the city’s first newspaper, established in 1863. The Intelligencer will move from weekly to daily publication in 1876 and five years later will merge with a competitor, The Post, to become the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

Venerable Press

The Gazette went through several changes in ownership and minor variations in its name before ending up in the hands of Samuel L. Maxwell (d. 1882), who christened it the Weekly Intelligencer. Maxwell, described by one of his contemporaries as “a first-class printer and a writer of considerable force,” bought the paper’s press, subscription list, and other assets for $300 in July 1867 (Grant, 365). The Gazette had suspended publication the previous month because the then-owner, I. M. Hall, had been elected King County Auditor, and “the prospect of steady remuneration was so alluring that he allowed the publication to die” (Bagley, 191).

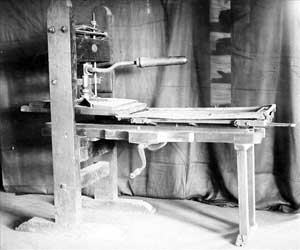

Maxwell produced his Weekly Intelligencer on the same hand-cranked, wooden-frame press that had been used to print the Gazette, as well as other pioneer newspapers up and down the West Coast. Manufactured in Philadelphia around 1820 by noted pressmaker Adam Ramage, the press differed little from the model used by Benjamin Franklin in the 1730s. It was shipped first to Mexico and then, in 1834, to Monterey, California (then Mexican territory), reportedly arriving on the back of a mule. It was used for a number of years to print governmental proclamations and other official documents. It passed into private hands during the Mexican-American War of 1846. In short order, the venerable press was used to print the first newspapers published in Monterey (the Californian, 1846); San Francisco (the Star, 1847); Portland (The Weekly Oregonian, 1850); Olympia (the Columbian, 1852), and Seattle (producing the first issue of the Seattle Gazette on December 10, 1863).

Two Newspaper Town

The Weekly Intelligencer enjoyed a monopoly in the rapidly expanding young town of Seattle until October 24, 1870, when Thomas G. Murphy began publishing what he initially called The Alaska Times but soon renamed the Puget Sound Dispatch. Murphy sold the paper to Charles H. Larrabee and Beriah Brown (1815-1900) in September 1871. A year later, Larrabee and Brown turned the weekly Dispatch into a daily -- the first daily newspaper to be published in Seattle.

Whether it was the increasing competition or for other reasons, Maxwell lost his taste for the newspaper business. He sold his paper to David Higgins for $3,000 in 1874 -- a 900 percent return on his initial investment of $300, seven years earlier. (It is said that Maxwell took his money and went to California, remaining there for some years. He eventually returned to Seattle, where he died under mysterious circumstances. In January 1882, his body was found floating in Elliott Bay close to Henry Yesler’s wharf. He had disappeared several weeks earlier.)

Maxwell’s successor, Higgins, made a number of improvements to the Weekly Intelligencer, beginning with the purchase of a new press. The old Ramage was retired from active duty. It was eventually donated to the University of Washington and later to the Museum of History & Industry (where it remains). Higgins also expanded the paper to daily publication, beginning on June 5, 1876. He hired additional staff to help produce the Daily Intelligencer, including two editors who eventually became part-owners of the paper: Thaddeus Hanford and Samuel L. Crawford. Hanford, eldest son of Seattle pioneers Edward and Abby Hanford, bought the paper from Higgins for $8,000 in April 1878. A land speculator as well as a journalist, he acquired the rival daily, the Dispatch, in a land swap in September 1878. A few months later, he bought the weekly Pacific Tribune, which Thomas W. Prosch (1850-1915) had established in 1875. Both papers were folded into the Intelligencer.

Despite the acquisitions (or perhaps because of them), Hanford began to flounder financially. In 1879, he asked Prosch to join him as co-owner. Prosch bought a half-share in the Intelligencer, but the two proprietors were soon at odds. Hanford ended up selling his share to then-city editor Crawford, for $5,000.

Meanwhile, in October 1878, a new daily had entered the Seattle market. Called The Post, it was backed primarily by John Leary (1837-1905), a lawyer (and eventually a mayor of Seattle) whose wide-ranging investments included real estate, railroads, banking, and mining. According to historian Clarence B. Bagley, the Post Publishing Company “got into debt from the start.” In addition to higher-than-anticipated operating costs, the company also undertook the construction of a substantial brick building on the northeast corner of Yesler Way and Post Street. The financial strains “continued from bad to worse” (Bagley, 192). In 1881, Leary and the Post’s other stockholders cut their losses by arranging a merger with the Intelligencer. The Intelligencer abandoned its offices in a wooden building owned by Henry L. Yesler (1810-1892) at Cherry Street and Front Street (1st Avenue) and moved into the newly completed Post building. The combined paper, named the Post-Intelligencer, rolled off the presses for the first time on October 1, 1881.