The Seattle Post-Intelligencer -- the city’s oldest newspaper, founded when Seattle was little more than a sawmill, a few dozen wooden buildings, and a couple of hundred souls -- survived the Great Fire of 1889; the Panic of 1893; the Depression of the 1930s, and decades of cutthroat competition with its cross-town rival, The Seattle Times. But it could not withstand the tectonic shifts that swept over the newspaper industry in the early twenty-first century. Revenue shrank as readers and advertisers migrated to the Internet. The Hearst Corporation, owner of the P-I since 1921, put it up for sale and then, after failing to find a buyer within 60 days, shut it down. The final print edition was published on March 17, 2009. The P-I “brand,” however, lives on. One day after abandoning newsprint, the Post-Intelligencer became the first major metropolitan daily in the country to adopt a web-only format, morphing into what Hearst called a “news product” that exists solely in cyberspace, at seattlepi.com.

From Aggregator to Aggregator

The move was both a leap into the future and a look back to the past. With a staff of only about 20 (compared to roughly 170 in the former newsroom), seattlepi.com will produce relatively little content of its own. Instead, it has been designed to function largely as an aggregator: a website that links users to other websites. Likewise, there was little original content in early versions of the P-I, when editors filled their pages mostly with articles clipped from other newspapers. In that sense, what remains of the P-I in the digital age echoes the version that was born on a hand-cranked wooden press in 1863, in a community that was still years away from seeing its first typewriters, telephones, or electric lights -- and more than a century away from its first computers.

The end of the ink-on-paper Post-Intelligencer brought expressions of dismay and sadness from many in the broader community, including some who had themselves abandoned print for online media. Washington Governor Chris Gregoire said she was in “a state of shock.” David Boardman, managing editor of The Seattle Times, sent an email to the P-I saying he and his colleagues “take no joy” in the closure of their longtime rival. “Whatever future there is for a daily newspaper in Seattle will be built upon the legacy of courageous, competitive journalism we've built together with you over the decades," he wrote (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, January 9, 2009). “I am really heartbroken,” reader Joanne Conger of Everett wrote in a letter published in the final edition of the P-I’s Sunday “Focus” section, “and hoping for some miracle” (P-I, March 15, 2009).

On the other hand, a number of readers expressed sentiments similar to these, posted as a “Soundoff” on seattlepi.com by a user identified as “sailbum”: “Good riddance to what is nothing more than another left wing rag.”

Gallows humor was the order of the day in the newsroom as Hearst’s deadline for selling the paper or shutting it down approached. One staff email chain included quotes ranging from singer Mick Jagger (“There’s fever in the funkhouse now”) to Xena, Warrior Princess (“no matter what we do, we still end up as food for the worms”). Possibly the best line was this one, attributed to author (and former P-I copy editor) Tom Robbins: “It only Hearst when you laugh” (twitter.com).

“Sufficient for the Time and Place”

The origins of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer can be traced to December 10, 1863, and the publication of Volume 1, Number 1 of The Seattle Gazette. The four-page weekly was edited, published, and distributed by James R. Watson, an itinerant printer most recently from Olympia. “After considerable vexation and delay, owing to a want of mechanical assistance in fitting up and arranging our printing apparatus, we are enabled to present the public with the first number of the first paper ever printed in Seattle,” he wrote in an inaugural message to readers. “It is neither so large as a barn door nor the London Times; but it is the best we can offer for a beginning and is, we trust, sufficient for the time and place.”

Born in Ohio in 1824, Watson had come west during the 1849 gold rush to California. He arrived in Olympia, by way of Victoria, British Columbia, in 1861. He ended up as the proprietor of Olympia’s Overland Press after its previous owner was shot to death, on January 7, 1863. That summer, Seattle pioneer Henry L. Yesler (1810-1892) offered Watson rent-free quarters and other inducements to establish a Seattle paper. Watson published a prototype, called The Washington Gazette, datelined Seattle, August 15, 1863, but actually printed in Olympia. Encouraged by the response, he packed up his printing press, and moved north.

Watson’s “printing apparatus” was Ramage Model No. 913, a flatbed, wooden-frame press that had been built some 40 years earlier in Philadelphia by famed pressmaker Adam Ramage. The press was shipped first to New York and then to Mexico, where it was used to print governmental edicts. Mexican officials sent it to Monterey, California, in 1834, reportedly on the back of a mule. It passed into private hands in 1846, after the Mexican-American War. In short order, it was used to publish the first newspapers in Monterey (the Californian, 1846); San Francisco (the Star, 1847); Portland (The Weekly Oregonian, 1850); and Olympia (the Columbian, 1852).

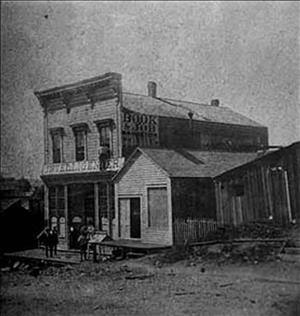

Watson installed the press on the second floor of a wooden building owned by Yesler, on the southwest corner of what is now Yesler Way and 1st Avenue S. Nearly every business in town was represented with an advertisement in the first issue. For residents of the fledgling community, a newspaper symbolized civic stability: It meant their town had a future.

Modest Beginnings

Seattle’s first newspaper was a modest affair, with small headlines, dense type, no photos, no other illustrations, and no color. Subscriptions cost $4 a year. Watson was editor and sole reporter (signing his work “Old Ollopod”), as well as business manager, typesetter, pressman, and mailing clerk. He gathered news primarily by showing up at the dock when a ship came in and collecting the bundles of papers arriving from other cities. He clipped articles about the Civil War from the Eastern papers and relied on papers in Olympia and Vancouver for regional news.

When the day’s work ended, he often repaired to one of the town’s saloons, setting a precedent honored by many of his successors. He was “the central figure of a coterie of jovial spirits which congregated ‘on the sawdust,’ “ as one admirer put it, referring to regular nightly gatherings “at some place with a bar, a large red-hot stove, a score or more of chairs with rawhide bottoms and a sawdust-covered floor” (Grant, 364).

Also like his successors, Watson struggled to find the subscribers and advertisers needed to continue his “little sheet” as a paying venture. Complaining about the paper’s “very slim patronage” after three months of publication, he told readers “we are willing to share the losses equally with the rest, but we would rather not work for nothing” (Seattle Gazette, February 23, 1864). He had to skip one issue in March 1864 because a part-time assistant got “gold fever” and ran off to Idaho. That month, Watson launched a subscription contest and promised to distribute $800 worth of prizes to the winners. He canceled the offer on April 19, saying not enough new subscriptions had come in. In June, he was forced to suspend publication for two months.

The paper reappeared on August 6, 1864, with a new name -- The Seattle Weekly Gazette. For a brief period a few months later, Seattle was a two-newspaper town. The semi-weekly People’s Telegram published its first issue on November 3, eight days the inauguration of telegraph service to Seattle. Watson shoved the challenger aside by issuing “extras” whenever important news arrived by telegraph. The Telegram was gone by the end of the month, the first of many “wrecks, great and small … along the journalistic highway” through Seattle (Bagley, 1929, p 468).

Birth of the Intelligencer

Watson continued to publish more or less regularly for about a year before turning the Gazette over to Robert G. Head and the Seattle Publishing Company. The paper passed through three other owners and several minor changes in its name before ending up in the hands of Samuel L. Maxwell (d. 1882). Maxwell, “a first-class printer and a writer of considerable force,” paid $300 for the Gazette’s Ramage press, subscription list, and other assets (Grant, 365). He rechristened the paper the Weekly Intelligencer. The first issue was published on August 5, 1867. At eight pages, it was double the size of the old Gazette, and carried more than twice the advertising.

Maxwell sold the paper seven years later to its editor (and his brother-in-law), David Higgins, for $3,000 -- 10 times what he had paid for it. He was the first Seattle newspaper owner to realize much of a profit on his investment.

Higgins made a number of improvements to the Weekly Intelligencer, beginning with the purchase of a new press. The venerable Ramage was retired from active duty and eventually donated to the University of Washington. It was hauled off to the campus, by wagon, just a few days before the Great Fire of June 6, 1889 -- a fact that saved it from almost certain destruction. (It is now in the safekeeping of the Museum of History & Industry.)

The new press, a Potter cylinder model powered by a steam engine, was installed in the basement of the paper’s new home, a two-story, wooden frame building constructed by Henry Yesler at Front Street (1st Avenue) and Cherry Street. With the press in place, Higgins began publishing the Intelligencer as a morning daily, beginning with the issue of June 5, 1876. He also expanded the staff, hiring two editors who eventually became part-owners: Thaddeus Hanford and Samuel L. Crawford.

Merger with The Post

Hanford, eldest son of Seattle pioneers Edward and Abby Hanford, bought the Daily Intelligencer from Higgins for $8,000 in April 1878. Seattle was a three-newspaper town at that time. Hanford quickly rolled over the competition. He acquired the daily Puget Sound Dispatch from owner and editor Beriah Brown (1815-1900) in September 1878, swapping a piece of farmland for the paper’s assets. A short time later, he bought the weekly Pacific Tribune from its owner, Thomas W. Prosch (1850-1915). He folded both papers into the Intelligencer.

Despite the acquisitions (or perhaps because of them), Hanford began to flounder financially. In 1879, he asked Prosch to join him as co-owner of the Intelligencer. Prosch bought a half-share, but the two proprietors were soon at odds. Hanford ended up selling his share to then-city-editor Crawford for just $5,000.

Meanwhile, in October 1878, a new daily had entered the Seattle market: The Post. Founded by brothers Kirk C. and Mark Ward, it was backed primarily by John Leary (1837-1905), a lawyer (and eventually a mayor of Seattle) whose wide-ranging investments included real estate, railroads, banking, and mining. According to historian Clarence B. Bagley, the Post Publishing Company “got into debt from the start” and “continued from bad to worse” (Bagley, 1916, p. 192). The construction of a three-story brick headquarters for the company, at the substantial cost of $30,000, added to the financial strains. In 1881, Leary and the Post’s other stockholders cut their losses by arranging a merger with the Intelligencer.

The Intelligencer moved into the newly completed Post building, on the northeast corner of Yesler Way and Post Street. The combined paper, named the Post-Intelligencer, rolled off the presses for the first time on October 3, 1881. Kirk C. Ward, former editor of The Post, promptly established The Seattle Daily Chronicle, precursor to what would become the P-I’s great rival: The Seattle Times.

“Live Hard, Die Easily”

Seattle at the end of the nineteenth century was a town where newspapers were “like so many people,” wrote Clarence Bagley, at one time a part-owner of the Post-Intelligencer. “They live hard and die easily” (1916, p. 189). Roughly 20 papers had followed The Seattle Gazette into print (name changes and spotty records make it difficult to track the exact number); only a handful survived to challenge the P-I.

The P-I owed its preeminent position in part to Leigh S. J. Hunt (1855-1933), its owner and publisher from 1886 to 1894. An Indiana-born educator and businessman, Hunt lavished money on the paper. He bought the latest equipment and hired the best talent he could find, including Horace Cayton (1859-1940), Seattle’s first African American journalist, assigned to cover politics. Hunt had already ordered a new press for the paper when the Great Fire of 1889 destroyed the P-I’s building and much of its equipment, along with most of the rest of downtown Seattle. Hunt personally directed the effort to salvage what could be saved from the P-I building and move it to temporary quarters, in a house and barn that he owned. The P-I continued publishing, without missing a single edition.

Three months after the fire, the P-I moved into a new building, at 2nd Avenue and Cherry Street. In addition to the new press, it was outfitted with state-of-the-art engraving equipment, for the reproduction of photos and other illustrations; and its first linotype machines, which greatly speeded up the production process.

Hunt financed his improvements to the P-I in part with profits made in mining and real estate. But he lost virtually everything during the Panic of 1893 and was forced to sell the paper. A group of Ohio-based investors took over in May 1984. Hunt went on to make and lose other fortunes, through ventures as far flung as gold mining in Korea and cotton production in the Sudan, before settling in Las Vegas in 1923. He left many marks on Seattle, including Volunteer Park, created as a result of one of his civic campaigns. Hunts Point, near Bellevue, bears his name.

The P-I went through several changes of ownership during the next few years, but it continued to gain in circulation and influence. It acquired the assets of one of its few remaining competitors, the Seattle Telegraph, in early 1896. Only The Seattle Daily Times, the survivor of an amalgamation involving the Chronicle, the Seattle Daily Call, and the Seattle Daily Press, remained standing. This was the journalistic landscape that presented itself to bankrupt publisher Alden J. Blethen (1845-1915) in the summer of 1896.

The Colonel and the Klondike

Blethen, a native of Maine who affected the title of “Colonel,” arrived in Seattle nearly destitute after a ruinous newspaper war in Minneapolis and a failed publishing venture in Denver. He and his wife and three children lived for several months on the charity of a brother-in-law. Disguising his desperate financial condition, Blethen managed to find a backer -- another self-styled “colonel” named Charles Fishback -- and engineered the purchase of The Seattle Daily Times. The first issue to be published under his imprint appeared on August 10, 1896.

The Post-Intelligencer at that time was the voice of the establishment, well-heeled and staid. Its circulation nearly equaled that of all the other papers in the state combined. The Times was an anemic, four-page afternoon daily with a circulation of probably no more than 4,000 (although it claimed 6,000). An admirer of William Randolph Hearst (1863-1951), Blethen took on the P-I in the way Hearst’s New York Journal had challenged Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, in a bare-knuckle war for readers and advertisers. “He wanted to goad The P-I into a fight,” write historians Sherry Boswell and Lorraine McConaghy; “he did not want a competitor -- he needed an enemy” (p 98).

The presidential campaign of 1896 provided the initial battleground. The P-I -- strongly Republican since its origins during the Civil War -- backed Republican William McKinley (1843-1901). Blethen endorsed William Jennings Bryan (1860-1925), the Democratic and Populist nominee. A political chameleon, more inclined to the Republican Party than any other, Blethen recognized the value of the political contest as a metaphor for the conflict between the newspapers. It was “the plucky Times underdog taking on the strapping P-I bully” (Boswell and McConaghy, 98).

Both papers were shamelessly partisan. Republican rallies received extravagant coverage in the P-I and a few paragraphs on the back page of The Times. Likewise, Populist gatherings earned ten-deck headlines on page one of The Times and barely a mention in the P-I. Incited by The Times, a mob of Populists gathered outside the office P-I publisher James D. Hoge one night and “cheered him with vocal assurance that they would hang his body on a sour apple tree” (Bagley, 1916, p. 194). The P-I, in turn, often sneered at the “Populist evening paper,” but chose not to dignify The Times by naming it.

The Times’ circulation jumped during the heat of the campaign. Blethen claimed it nearly doubled in three months. However, readership and advertising fell sharply after McKinley won the election in November. Operating funds dried up; losses mounted. The Times might have joined its predecessors in Seattle’s journalistic graveyard but for the discovery of gold in the Klondike, in July 1897.

News of the discovery reached Seattle through the efforts of P-I reporter Beriah Brown Jr. (son of the founder of the old Dispatch), who chartered a tugboat to intercept a steamer that was bringing gold back from the Klondike. He spent an hour on deck interviewing miners, then rushed back to Seattle in time to break the news with a famous headline: “Gold! Gold! Gold! Gold!” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 17, 1897).

The Klondike gold rush proved to be a tide that lifted both The Times and the P-I to new heights. As historians Sherry Boswell and Lorraine McConaghy have pointed out, “Only the luckiest argonauts would return with gold, but every man needed information, outfitting, and relaxation.” Both papers published special guides to the Yukon, with maps and lists of necessary supplies. They grew fat with advertisements from outfitters, assayers, retailers, and others hoping to separate the miners from some of their money. Circulation jumped. It was, in short, “a terrific time to own a newspaper” (109).

Slug Fest

Seattle in 1900 was a three-newspaper town. The afternoon Star joined the mix in 1899 (and left it in 1947), but the real contest was between the P-I and The Times. The P-I was the “organ” of the “silk-stockinged” set: conservative, respectable, a little prudish. The Times was splashy, bold, and a little vulgar. And by 1904, it had overtaken the P-I in circulation and advertising.

The Times gained the edge by embracing the style of journalism that had been pioneered by Hearst and Pulitzer in New York: using big, bold headlines; putting more emphasis on stories involving crime and scandal; incorporating more photographs and illustrations; adding color. Its detractors called this “yellow journalism,” after a comic strip character called “the Yellow Kid.” The Times introduced color to its pages in 1903, initially using it only on its comics and Sunday features but soon splashing it throughout the paper, including on the front page. John L. Wilson (1850-1912), owner of the P-I from 1899 until selling it in August 1912, reportedly said he would never publish a paper in color -- he considered it garish -- but the steady gains in circulation by The Times forced him to change his mind.

The papers gained not only color but heat after 1904, when Wilson hired Erastus Brainerd (1855-1922) as the editor of the P-I. Brainerd, a native of Connecticut, was educated at Harvard and enjoyed success as an art critic and curator in Europe before ending up in Seattle in 1890. He edited the Press-Times (a precursor to Blethen’s Times) until hard times hit that paper in 1893, and then served as a state land commissioner and later as head of the Seattle Klondike Information Bureau. Wilson had been elected to Congress from Spokane after Washington attained statehood in 1889 and later served one term in the Senate, losing a bid for re-election in 1898. He bought the P-I (with the help of railroad magnate James J. Hill) the next year. Some historians speculate that Wilson hired Brainerd because he wanted an attack dog -- someone who could go after his opponents and restore his position as a political power broker.

The war of words escalated immediately. Blethen variously described Brainerd as an “imbecile,” a “pinhead,” and a “crooked and crack-brained whelp.” Those insults were mild compared to ones that Brainerd flung at Blethen. “Dastardly and desperate, with failing fortune and mind, with only the rancid remains of a foul character, Blethen, a social pariah and outcast, seeks to drag down to his own abysm of degradation all who are engaged in the business which he disgraces and defiles,” he wrote in one particularly fulminating editorial (P-I, November 6, 1904).

Brainerd was a strong supporter of the Rev. Mark Matthews (1867-1940), the fiery minister of the First Presbyterian Church and a leader in the effort to subdue various manifestations of “vice” in Seattle. Blethen was less inclined to cluck about the city’s dance halls, saloons, and gambling emporia. When he was indicated by a grand jury in May 1911 on charges of libeling a city councilman and conspiring to protect illegal gambling, prostitution, and liquor sales, Brainerd was almost beside himself. Blethen, in turn, filed a $100,000 libel suit against the P-I for Brainerd’s scathing editorials about the indictment. Blethen was cleared of the charges. Brainerd was fired. The animosity between the two papers eased, until 1921 and yet another change of ownership for the P-I.

Hail to “The Chief”

On April 10, 1921, a Seattle lawyer named John H. Perry announced that he had purchased the P-I. Many people suspected there was a hidden owner, but Perry denied it. However, the P-I immediately added features from the chain of newspapers owned by William Randolph Hearst, known to his underlings as “The Chief.” It also adopted the layout style used by Hearst papers. On May 21, Perry moved the P-I to a new location at 6th Avenue and Pine Street. Then he named Lester J. Clarke as the paper’s publisher and abruptly left town.

What had long been rumored was not confirmed until December 27, 1921, when the P-I published a front-page editorial by Hearst -- its actual owner for some eight months. Hearst had gone on a buying spree that year, picking up newspapers in Detroit and Boston as well as in Seattle, using agents to make the purchases on his behalf. (He added five more papers to his collection the next year.)

With the resources of the most sophisticated newspaper chain in the country at its command, the P-I quickly regained its position of dominance in Seattle’s newspaper market. Circulation surged to nearly 62,000 daily and 138,600 Sunday in 1921, compared to about 56,500 daily and 84,000 Sunday for The Times. C. B. Blethen, who had succeeded his father as publisher of The Times after Alden Bethen’s death in 1915, spent money furiously in an effort to fend off Hearst. The competition was so costly, he said later, that "The Times made a net loss in that year of more than $64,000, and we found ourselves fighting for our business lives. From that time forward we were compelled to readjust all of our ideas and expend enormous sums of money annually to maintain our circulation and prestige" (Boswell and McConaghy, 250-251).

On Strike, 1936

Long-simmering tensions between Hearst’s managers and the staff at the P-I flared into open animosity in the 1930s, resulting in one of the first successful strikes by white-collar workers in the United States. Hearst was deeply suspicious of efforts by the fledgling American Newspaper Guild to organize workers at the P-I. Reporters who were thought to be sympathetic to the union were given undesirable assignments. “Efficiency” standards sometimes resulted in the firing of experienced staffers and their replacement by younger people who were willing to work longer hours for less pay. Management adamantly refused to recognize the guild as the bargaining agent for the newsroom. When two popular staff members -- chief photographer Frank Lynch and reporter Everhardt Armstrong -- were fired, apparently because of their affiliation with the union, 35 of their colleagues (half the newsroom) walked off the job.

The strikers set up a picket line outside the P-I building, at 6th Avenue and Pine Street. It seemed a hopeless cause at first, with only a few dozen people walking the line. But the strikers were soon joined by members of other unions, including the powerful Teamsters. Within a few days, the P-I building was surrounded by about 1,000 picketers, a living wall of union solidarity.

The P-I attempted to continue publishing by using the presses and composing room of The Times, but unionized typographers at the rival paper prevented that. Publication was suspended for the first time in the P-I’s history. Finally, after 15 weeks, Hearst management capitulated. The strikers went back to work on November 29. They won a few new benefits, including two-weeks of vacation pay and a severance package, but above all, recognition for the Newspaper Guild.

In what was seen as an effort to restore peace, Hearst almost immediately named a new publisher for the P-I: John Boettiger (1900-1950), a former reporter for the Chicago Tribune and, more important, son-in-law of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had just been re-elected to his second term. The paper was struggling financing, with strike-related losses compounded by the ongoing Depression, and Boettiger was given much more freedom to direct news, editorial, and business operations than was customary for a Hearst publisher. His wife, Anna (eldest daughter of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt), was named assistant editor with special responsibility for the “Homemaker” section.

Although Boettiger had little experience in newspaper management and Anna had none, the P-I made advances in circulation and advertising under their leadership. The paper tilted left on its editorial pages, strongly supporting Roosevelt’s New Deal. In 1943, however, Boettiger left to join the Army. Anna edited the paper on her own for a short time, but then moved into the White House to become a special assistant to her father. Hearst appointed Charles B. Lindemann as acting publisher during Boettiger’s absence. After the war, Boettiger resigned, the “acting” was dropped from Lindemann’s title, and the P-I tilted back to the right.

“Hello Sweetheart, Get Me Rewrite”

The P-I in the 1950s could have been a stand-in for the newsroom depicted in the classic play (and later movie, several times over), “The Front Page.” The paper had moved into its 10th, and penultimate, home, built at a cost of $5 million at 6th Avenue and Wall Street. A stunning globe on top of the building announced “It’s in the P-I,” in huge glowing letters that rotated red against deep blue. The continents were highlighted in green. The eagle that perched on the globe, ready for flight, was 18 and a half feet tall, magnificent in gold. It was a bold symbol for a paper that had suddenly become a scrappy underdog, fighting for market share against an increasingly dominant Times.

This was the decade that defined the stereotypes that would carry The Times and the P-I into the twenty-first century. The Times, located at Fairview Avenue and John Street, was “Fairview Fanny” -- stodgy, conservative, the button-downed Republican who never missed a church picnic. The P-I was the thrice-divorced fellow who could be counted on to go off on a bender from time to time. Sports columnist Art Thiel, who began working at the P-I in 1980, once said he could sum up the differences between the two papers with one word: In The Times, victims were found half-clothed; in the P-I, they were half-naked.

The P-I’s home, from 1948 until 1986, was an art deco building originally designed as two stories; a third floor was added in 1969. The presses were in the basement. Type was still being set in hot lead, on linotype machines. News from the wire services came in on teletype machines. Reporters wrote their stories on manual typewriters. The place rumbled when the presses were rolling and clattered the rest of the time. The linoleum floors and metal desks helped amplify the noise level. There were ashtrays on nearly every desk, and bottles stashed away in many of the drawers.

It was the kind of world where a man in a fedora could grab a black rotary dial phone and say “Hello sweetheart, get me rewrite,” and the secretary on the other end would punch the call through.

“The P-I city room in 1952 was so masculine that entering it felt like making a wrong turn into the men’s room,” reporter Barbara Huston recalled in 1986. “My own desk was down the hall in the sanctuary of the women’s pages, a ladylike bastion of people who wore hats and gloves when they went out, and wrote about weddings when they stayed in” (Huston, “No Place for a Lady”).

No doubt some of the stories that have passed into P-I lore about those years have been polished by embellishment. Some say a reporter named Fergus Hoffman disappeared for a week after being sent to Alaska to cover the Good Friday earthquake of 1964 and then sent a bulletin saying “The liquor store in Nome was undamaged.” Others say he was only AWOL for a day before phoning from a bar in Anchorage. Author Tom Robbins freely admits to regular breaks on the roof to smoke non-tobacco products when he worked on the P-I copy desk in the mid-1960s, and says he wasn’t alone. Still, the paper always got out in time.

One sign that things have changed is the fact that P-I employees who were offered full-time jobs at the post-print seattlepi.com were required to take drug tests before being hired.

Business Partners; Editorial Rivals

The P-I steadily lost ground to The Times in the battle for readers and advertisers in the years after World War II, to the point that the older but weaker paper appeared close to collapse by the 1980s. At that point, the Hearst Corporation and The Seattle Times Company applied for a Joint Operating Agreement (JOA) under the Newspaper Preservation Act of 1970. The act -- an effort to encourage newspaper competition in major markets -- allowed daily papers to merge business functions, in ways that would otherwise violate antitrust laws, if the Justice Department determined that one of them was in danger of failing. Critics called it protectionist legislation that would benefit publishers more than the public. Supporters said it would promote editorial diversity, keeping two newspapers alive even if market forces would support only one.

The Times and P-I applied to the Justice Department for approval of a JOA in 1981. The application was strongly opposed by a coalition that included weekly and suburban newspapers, several prominent advertisers, the Pacific Northwest Newspaper Guild, and a number of P-I employees. After a lengthy court battle, the JOA was approved. It took effect on May 23, 1983.

The agreement gave The Times control over production, delivery, advertising, circulation, and marketing for the two papers, in return for two-thirds of the profits of the joint operation. The same presses were used to publish both papers -- the P-I in the morning, and The Times in the afternoon. The news and editorial departments remained separate, independent, and competitive. No longer needing its presses or composing room, the P-I moved into its 11th and final home, a sleek new building on Elliott Avenue, in 1986, taking the globe with it.

Initially, the agreement seemed to be attaining its objective. The P-I’s circulation increased by 7 percent between 1983 and 1988. The Times’ circulation also increased, by 5 percent. "The JOA means we aren't wasting money going head-to-head with the P-I," said publisher Frank Blethen, the fourth member of the Blethen family to head The Times. "Instead we are doing what we should really be doing, which is serving the reader and advertiser by putting money back into the product instead of dealing with the competition across the street" (The Seattle Times, May 22, 1988).

Privately, however, Blethen was chafing at a restriction in the JOA that limited The Times to afternoon publication, a position that few newspapers with morning competitors found profitable. At his behest, The Times renegotiated the JOA, effective March 6, 2000, granting certain concessions to Hearst in return for the right to publish in the morning. Many observers questioned why Hearst would give up what appeared to be its most valuable asset: its monopoly on morning publication. David Brewster, former publisher of the Weekly, was among those who concluded that it was the beginning of the end for the P-I. "It sounds to me as if Hearst is preparing to close up shop in Seattle," he wrote in a 1999 article in The Times.

Indeed, the P-I’s circulation dropped steadily after the amended JOA took effect, from 192,000 in March 2000 to 117,000 by the time the plug was pulled, in March 2009. (Circulation at The Times also declined, but at a slower rate.) But the revised JOA also gave the P-I the right to fully develop its nascent website. The site, launched in April 1996 as SeattleP-I.com, was initially limited to posting content from the P-I’s travel, outdoors, and neighborhood sections. News content was prohibited under the terms of the JOA. The expanded website, renamed seattlepi.com, quickly outstripped the competition. In January 2009, Nielsen ranked it among the top 30 newspaper websites in the country, with an average of 4 million visitors a month.

End of the Line

On January 9, 2009, Hearst executives confirmed a rumor that had been leaked to KING-TV the previous day: the paper that William Randolph Hearst had bought 88 years earlier was being put up for sale. If a buyer could not be found within 60 days, the paper would be closed. Left open was the possibility of creating a digital-only operation, with a greatly reduced staff. But in no case would Hearst continue to publish the P-I in printed form. The paper had been losing money every year since 2000 and Hearst saw no possibility that the hemorrhage could be staunched.

"We've been on the knife edge all this time," said P-I managing editor David McCumber. "We finally slipped" (P-I, January 9, 2009).

To no one’s surprise, no buyer appeared. Newspapers around the country have been struggling to survive what one writer called “the twin typhoons” of recession and the Internet. Retail stores, car dealers, and other major advertisers cut their budgets in the face of a deepening recession. The Internet siphoned both readers and advertisers from traditional media. People who once bought newspaper classified ads turned to Craig’s List and other free Internet marketplaces. In her elegy for the P-I, writer Carol Smith summed it up this way: “Cause of death -- a fatal economic spiral compounded by dwindling subscription rates, an exodus of advertisers and an explosion of online information” (P-I, March 17, 2009).

The final edition of the printed P-I was published on St. Patrick’s Day, 2009. It included a 20-page commemorative section that featured a full-color shot of the celebrated globe on the front page, with the headline "You’ve meant the world to us." The press run, three times the normal subscription run of 117,600, quickly sold out.

Among the subscribers who received their copy on a front porch, wrapped in the familiar red plastic sleeve, was one who sent this message to the staff, via reader representative Glenn Drosendahl: “My heart goes out to all of you at the P-I. Thank you for the dedication and passion you have given us over all of these years. I wish you all the best. I feel like I have lost a dear friend. I can't even read the last edition yet, I am just looking at it lying in its little red plastic casket. Maybe later.”