On October 15, 1991, Bankruptcy Court Judge Frank D. Howard approves a settlement agreement that ends two years of controversy and litigation over who owns and controls 11 historic buildings that make up most of Pike Place Public Market, the defining landmark of downtown Seattle. The dispute arises from a complex series of real-estate transactions in the early 1980s through which the Urban Group, a private investment group based in New York, gained legal title to the market buildings, ostensibly in a tax-shelter deal that provided $3 million for market renovations. The "sale" of the market became public in 1989 when the Urban Group demanded millions in back earnings and circulated plans to boost rents. Alarmed Pike Place Market supporters responded by organizing a Citizens Alliance to reclaim the market, prompting a flurry of lawsuits challenging the investors' title and countersuits by the investors. In 1991, after legal setbacks force it into bankruptcy, the Urban Group accepts a cash buyout of its interest and the public regains clear title to the historic Pike Place Market.

Public Market

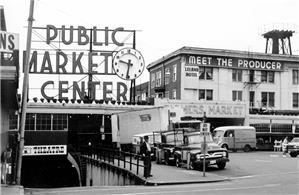

The struggle against the Urban Group marked the second time that citizen activists banded together to save the Pike Place Market. Founded in 1907 and largely constructed over the next decade, the Public Market consists of a long arcade of street stalls lining Pike Place on the bluff overlooking Seattle's waterfront, where vendors hawk fresh produce, flowers, fish, and crafts of all kinds, surrounded by a series of market buildings containing a warren of small shops and restaurants. Although it now draws many millions of visitors yearly, both locals and tourists, Pike Place Market nearly disappeared in the 1960s, when downtown business leaders and city officials targeted the area for urban renewal. That time, architect Victor Steinbrueck (1911-1985) founded and led the loosely organized Friends of the Market, which ultimately won a 1971 initiative vote preserving the market as an Historic District. The new fight would be led by Victor's son Peter Steinbrueck (b. 1957).

Two years after the Historic District was approved, the Seattle City Council created the Pike Place Market Preservation & Development Authority (PDA) to purchase and manage the buildings that made up the market. With considerable assistance from Senator Warren G. Magnuson (1905-1989), legendary for his ability to channel government spending to his home state, more than $50 million in federal funds flowed to the market during the 1970s, allowing the PDA to acquire most of the major market buildings and and begin much-needed rehabilitation and restoration. However, the money stopped flowing by the end of the decade as the economy tightened and Magnuson lost his seat in the 1980 election.

Private Investors

By early 1980, although much work had been done, substantial renovations were still needed and their cost far exceeded the rents that the PDA received from market merchants. It was then that PDA Executive Director John Clise and his staff turned to a tactic that other nonprofit agencies used to raise funds: selling tax depreciation rights (that a tax-exempt nonprofit does not need) by transferring legal interests in historic buildings to private investors who can claim the depreciation as a write-off against other income. Apparently assured by its lawyers that doing so would not risk the market buildings, the PDA looked for tax-syndication investors and quickly connected with the Urban Group.

Headed by New York tax and real estate lawyers Arthur Malman and Martin Major, the Urban Group already had invested in several area historic buildings, including Tacoma's Pantages Theater. In April 1980, the PDA and the Urban Group made their first deal, a "tax sale" contract for two market buildings, the Sanitary Market and the Cliff House, with an initial payment of $700,000 to the PDA. Over the next three years, in a complex series of deals spelled out in thousands of pages of legal documents, similar contracts were signed for eight more market buildings. Altogether the deals gave the Urban Group legal title to 11 market buildings or almost 90 percent of the public area that the PDA managed, in return for "down payments" totaling just under $3 million.

The "sales" contracts called for a total purchase price of over $20 million, far more than Pike Place Market's existing income would support, and PDA officials evidently assumed that the Urban Group investors would claim their tax breaks and default on the "purchase" when balloon payments for the rest of the price came due in the late 1990s. The investors were able to realize $10 million in tax savings, but then the federal Tax Reform Act of 1986 eliminated the tax breaks. By 1989, the Urban Group sounded less like tax investors and more like an absentee landlord. After auditing the PDA's books, the investors asserted that they were entitled to millions of dollars in market income, demanded that the PDA cut costs, and circulated plans for large rent increases.

Citizens Alliance

When the Urban Group's demands -- and its "ownership" of Pike Place Market -- became public in late 1989, an uproar ensued. Market vendors, newspaper columnists, and letter writers all joined in denouncing the New York investors. Many also criticized the PDA, asking how it could have sold the public's market. Among those was architect Peter Steinbrueck, who like his father before him organized an advocacy group -- the Citizens Alliance to Keep the Pike Place Market Public. Steinbrueck was able to assemble a high-powered team of local lawyers who volunteered their time on behalf of the Citizens Alliance and concluded, after analyzing the voluminous legal documentation, that there were strong grounds to challenge the deals between the PDA and the Urban Group. Seeking more legal firepower, Steinbrueck convinced Seattle City Attorney Mark Sidran to throw the support of the city's legal team behind efforts to keep the market public.

Under pressure, the PDA hired its own lawyers, including Gerald Johnson, Senator Magnuson's former chief of staff. Johnson advised the PDA that it needed a tough negotiator to deal with the Urban Group and the agency got one -- Shelly Yapp, a former Seattle deputy mayor. Yapp began as a consultant but by mid-1990 she became Executive Director of the PDA (a post she would hold for 10 often-contentious years), while continuing to play a lead role in the negotiations and litigation.

By the spring of 1990, the legal maneuvering culminated in in an array of lawsuits and countersuits between the four involved parties -- the Citizens Alliance, the City of Seattle, the PDA, and the Urban Group. All the cases ended up in the courtroom of veteran Superior Court Judge Frank L. Sullivan. Local market supporters won the first round on October 31, 1990, when Judge Sullivan announced a series of preliminary rulings in their favor. Soon after, the Urban Group found itself unable to pay its own lawyers.

Seattle's Soul Saved

The Urban Group responded by filing for bankruptcy in federal court in New York, putting Judge Sullivan's legal rulings (and the legal fees it owed) on hold and moving the battle to its home turf. Lawyers for Seattle and the PDA worked quickly to reverse this last effect, asking the New York judge to transfer the bankruptcy case to federal court in Seattle. PDA attorney Fred Tausend devoted his argument to history rather than legal citations, showing historic photos of Pike Place Market as he explained the importance of what he called "the soul of Seattle" (Shorett and Morgan, 159). Tausend and Sidran convinced the New York judge to send the case to the Seattle courtroom of U.S. Bankruptcy Court Judge Frank Howard.

When Judge Howard ruled in May 1991 that Judge Sullivan's orders could be enforced against the Urban Group, the investors appeared ready to settle the case and give up all interest in the market in return for cash to invest elsewhere. Led by Yapp, the PDA was willing to agree, although market vendors and others expressed disgust at having to pay off the New Yorkers and at the PDA for having created the problem. Putting aside their differences, the Citizens Alliance, the PDA, and the city jointly lobbied the state Legislature for money to fund the settlement, winning a $1.5 million appropriation. The city provided another $750,000 in public funds, and title companies who had insured the legal title that the Urban Group purchased kicked in $750,000 more, giving the investors a buyout of $3 million, equaling their initial investment.

The Urban Group approved the settlement in July 1991 but it took several more months to work out all the details. On October 15, 1991, Judge Howard officially approved the settlement, ending the Urban Group's involvement and returning the Pike Place Market to undisputed public ownership.