On May 1, 1908, grading crews complete the sculpting of the Rainier Vista out of the forest and hills of Seattle's University of Washington campus in preparation for the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific (A-Y-P) Exposition, a world's fair to be held at the university campus from June 1 to October 16, 1909. Crews smoothed the rough ground into an even slope leading down to the lakeshores and then terraced part of the slope into a series of level plains on which to build the exposition's temporary and permanent buildings. They cut a web of avenues into the hillside to provide access to the fairgrounds, some of which continue to serve the university today. John C. Olmsted (1852-1920), a landscape architect and partner in the Olmsted Brothers firm that created Seattle's park and boulevard system and an earlier plan for the university campus, developed the landscape plan for the exposition. The regrading created the campus that has served the university for the past centur, both in the space it created for continued growth and in its beauty.

Walking the Site

When John C. Olmsted (1852-1920) arrived to look at the grounds in October 1906, he found the lower campus covered in trees and dense underbrush. After a day spent walking around the grounds in the spring of 1907, he commented in a letter home that it was, "hard walking about the grounds because of the unevenness of the surface and the masses of underwood, even where the surveyors have cleared lines through" (Olmsted, April 2, 1907).

The site sloped down to the southeast, gradually in some places, steeply in others. Its slopes and thick forest inhibited development and limited building sites. Most of the existing university buildings sat atop the hill, where a sizable section of the campus was cleared and level enough for buildings. Future growth depended on opening for development the lower section of the campus, south of 41st Street. The forest had been cut over once, some years earlier, and the new growth was not valuable enough to finance the work of removing it.

The siting of a world's fair on campus provided the exposition with hundreds of acres of open space and the university with a means to make the space usable. In the tradition of other world's fairs of the era, Olmsted planned to transform the space into a park-like setting. The fair was mainly intended to sell region's resources, chiefly its forestry resources, but the grounds themselves would demonstrate that the region could match the beauty of any East Coast or European landscape. To that end, Olmsted's plan molded the hillside into an even slope leading to the lakeshores at its base with avenues and pathways cutting directly across the hill and in sweeping arcs.

Olmsted's plan called for the removing about 210,000 cubic yards of earth, some of which was used to fill in low areas and the rest of which was removed from the site. Hardpan nearly stymied the graders' efforts. After first trying to dynamite the dense layer of soil, which failed, crews drove teams of horses across the hillside dragging plows behind them. The hardpan proved so resistant to their efforts the crews kept blacksmiths on hand to sharpen the plows repeatedly.

Two prominent elements of the grounds did not need to be created by plows and shovels. The natural amphitheater, which lay where Padelford Hall and its parking garage are today, formed a perfect venue for speeches and performances. The exposition company just added seating and a stage. "The Park," a remnant of forest in the southeast corner of the grounds, was left relatively untouched, save for trails cut through it to allow visitors to enjoy the calm of the forest and lakeshore.

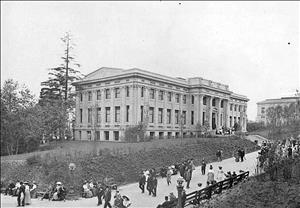

Once complete, the grounds presented a smooth, even slope that drew visitors' attention to the landscape in the distance via vistas framed by towering Douglas firs. The fair's entrance at 41st Avenue led visitors via Olympic Place to the top of the Court of Honor. From there Rainier Vista, with a view of Mount Rainier, lay directly ahead. Paths and avenues led off of the Court of Honor to other areas of the fair. Where, just two and a half years earlier, Olmsted had struggled to follow a trail, now ladies in dainty shoes and college students pulling visitors in rickshaws could traverse the campus easily.

In two places crews created passages under the railroad tracks, one at the base of the Rainier Vista and another at the foot of the Pay Streak, the fair's midway. Thousands of cubic yards of dirt had to be removed to make gradual approaches to the underpasses. The passages remain today, taking pedestrians under the Burke-Gilman Trail to the Triangle Parking Garage and the Magnuson Health Sciences Building.

After the fair closed on October 16, 1909, crews demolished the temporary buildings and cleared away the rubble. Within months the exposition's temporary city had disappeared, but its infrastructure remained. Roadways, including much of today's Stevens Way, and paths crisscrossed the campus. Most of the dense forest had been replaced by lawns, scattered stands of trees, and gardens. Where the temporary buildings had stood, the leveled terraces remained, ready for new foundations.

In the past century the university has gradually filled in those spaces and many more. Buildings encircle Drumheller Fountain, with just the Rainier Vista corridor remaining open. Parts of the design have shifted to accommodate new construction, but the basic structure of the campus remains as a space that has served both the university and countless visitors well.