The Bank of Commerce Building (common name, Yesler Building) at 95 Yesler Way, is located on the southwest corner of 1st Avenue S and Yesler Way and was one of three "legacy" buildings commissioned by Henry L. Yesler (1810-1892) to celebrate Seattle's pioneers. Designed by architect Elmer H. Fisher (ca. 1840-1905) and built in 1890-1891, it was called the Bank of Commerce Building after the first of the three start-up banks it incubated between 1891 and 1905. The others were the Scandinavian-American Bank and the Seattle State Bank. All three were instrumental in bringing eastern capital to rebuild Seattle after the Great Fire of 1889, and they supported fledgling businesses, especially those of immigrants from Italy and Scandinavia. Although a third floor, designed by Albert Wickersham (1891-1920), was completed in 1906, the banks eventually outgrew the space, and by 1911 they had all moved to other facilities. The following decades were hard on the entire Pioneer Square area, and this former home of banks was reduced to housing a shoe store, dentists' offices, an Army surplus store, the Afro-American Club, and other short-term tenants. After World War II, the Yesler Building became one of the many properties of landowner Sam Israel (1899-1994), and is currently owned by Samis, the foundation he established in 1987. In 1970, the Pioneer Square area where the building is located was designated as both a National Historic District and a local preservation district, and shortly thereafter the building was upgraded structurally and renovated. Today, in 2009, the building remains the property of Samis, and temptingly offers the Rocky Mountain Candy Company on the first floor and Skyn Spa upstairs.

A New Building for a New Bank

The man who was to be the building's first tenant, Robert R. Spencer (ca. 1855-1916), a banker from Iowa City, arrived on his first trip to Seattle in October 1888. He was touring the western reaches of the country looking for a home for a new bank he wished to organize, one that could grow from modest beginnings into a large enterprise. Obviously impressed with Seattle, he wrote:

"After carefully looking over the situation in the various cities along my route I had no difficulty in arriving at the conclusion that for a large corporation, Seattle is the place. With its large resources of iron, coal and lumber, splendid harbor and intelligent wide-awake citizens it is bound in my judgment to double in population and triple in wealth in the next five years. Already there is a stream of immigration flowing in that promises in spring to become a flood” (Marple & Olson, 11).

Spencer returned to Seattle in February 1889 with $72,500 in subscriptions to the new bank, and he stayed in the Occidental Hotel. By March 4 he had filled a board of directors for his "Bank of Commerce" by adding E. H. Alvord, M. D. Ballard, Richard Holyoke, W. H. Llewellyn, J. H. Elder and T. W. Prosch (1850-1915), all from Seattle. The directors elected Spencer to be cashier, which at the time was the equivalent of bank manager.

On May 15, 1889, Spencer opened his new bank in a space shared with Griffith Davies's bookstore on Front Street (now 1st Avenue) at the foot of Cherry Street. Three weeks later, on June 6, the Great Seattle Fire destroyed the premises, along with most of the city's commercial downtown area. But Spencer and his bank rebounded, opening on the second day after the fire in a tiny space in the Haley-Glenn Grocery, located in the brick Boston Block at 2nd Avenue and Columbia Street. A few days later Spencer moved the bank to a frame structure at 2nd Avenue and Cherry Street, where the Alaska Building now stands, and he hauled the bank 's books, papers, currency, and valuables to a public safe-deposit vault at the foot of Cherry Street twice each day.

For two years, Spencer conducted business from this makeshift arrangement, and the bank grew steadily. On July 21, 1890, the bank received its national charter and became the National Bank of Commerce. When the two-story Yesler Building on the southwest corner of Commercial Street (now 1st Avenue S) and Yesler Avenue (now Yesler Way) was completed by Elmer H. Fisher in 1891, Spencer's bank became the first tenant and the building became known as the Bank of Commerce Building. (There are two buildings in downtown Seattle commonly known as "the Yesler Building." The historic name of the first, which is the subject of this essay, is the "Bank of Commerce Building," and it is referred to herein by both its common and its historic name. The second "Yesler Building," built in 1909, is located at 400 Yesler Way. Its historic name is the "City Hall/ Public Safety Building," reflecting earlier uses. Both buildings are listed as historic sites with Seattle's Department of Neighborhoods. The first "Yesler Building" was what is now known as the Mutual Life Building at 601 1st Avenue, which replaced the Yesler-Leary Building that burned down in the Great Fire of 1889.)

Henry Yesler's Neighborhood

The Bank of Commerce Building was one of three legacy buildings Henry Yesler commissioned in honor of Seattle pioneers. The first to be built was the Pioneer Building at 600 1st Avenue, located at the site of Yesler’s pioneer home on the northeast corner of the intersection of Front and James streets. The Mutual Life Building, 605 1st Avenue, was across Front Street from the Pioneer Building. All three buildings faced Yesler Park, a triangular site donated to the city by Yesler and now known as Pioneer Square.

All three Yesler legacy buildings in their original form were designed and built by Elmer Fisher. He oversaw construction of the entire Pioneer Building, the basement and first floor of the Mutual Life Building, and the basement and first two floors of the Bank of Commerce Building. Additional floors, designed by others, were later added to the Mutual Life Building and the Bank of Commerce Building.

At the time he donated the park and started construction on the buildings, Henry Yesler had his business office on Yesler’s Wharf, located on the waterfront between Yesler Way and Columbia Street. His first sawmill, which was also the first steam-powered sawmill on Puget Sound, was on Yesler Way, between Front Street and Elliott Bay, about where Post Street is today. According to early historian Thomas W. Prosch, the Yesler Mill cookhouse, which was both the office for the mill and the center of social life in the new city, was built in 1852 on 1st Avenue S between Yesler Way and Washington Street.

An Architect's Vision

It is hard to know what was in Fisher’s mind when he designed this unusual ensemble of buildings, but it is possible that he was helping his client celebrate the sawmill business near its original location. University of Washington architecture historian Jeffrey Ochsner and preservationist Dennis Alan Andersen, speaking of the Bank of Commerce Building, note:

"The rugged stone [on the façade] gave the building a primitive rustic feeling (and seems almost to recall the size and shape of logs). The treatment echoed the detailing of the stone pilasters on Fisher’s Pioneer Building across the Square … .The ground floor stonework [of the Mutual Life Building] featured the same rounded rough-hewn texture as the Bank of Commerce across Yesler” (Ochsner & Andersen, 181).

Today the rugged stonework is most noticeable on the Bank of Commerce Building and the restored pilasters of the Pioneer Building.

Banks and More Banks

The Bank of Commerce was not the only bank in town, nor even the only one at 1st Avenue and Yesler Street. Five of the 18 banks in Seattle were on this corner, and their officers and cashiers were many of the businessmen and political figures who built the Pioneer Square we know today, and in honor of whom many of Seattle’s streets were named. The banks were anchor tenants in all three Yesler legacy buildings, all on the first floors, often in the corner spaces. In the period 1889-1892 the number of banks in Seattle tripled, following a statewide trend. In 1892, Seattle’s 18 banks reported $3,395,000 in capital, much of it from out of state. The rebuilding of commercial Seattle (Pioneer Square) after the Great Fire was financed in part by this capital.

The Bank of Commerce Building was small: the lot measured 24 by 70 feet, and the building had only two stories above ground and one below until the third floor was completed in 1906. The bank had a small staff -- Spencer was assisted by his brother, Oliver, who spoke Italian and served as Italian consul, bringing business to the bank from the Italian Americans who traded in the Pike Place Market. The Panic of 1893, which lasted until 1897 in Seattle, stifled growth in both banking and industry. Once it passed, largely as a result the Klondike Gold Rush, pressure began to build for the banks to grow: “The challenge to a bank was to grow at least as fast as its customers. A national bank was permitted to lend no more than 10 percent of its capital and surplus to any one customer” (Marple & Olson, 57).

As Seattle boomed to support the gold rushes, customers needed more money than they could get from a single bank. Bank mergers resulted. The National Bank of Commerce moved to the Bailey Building at 2nd Avenue and Cherry Street in 1897, and in 1909 it merged with Washington National Bank. Eventually, many mergers later, what had started as the National Bank of Commerce became Rainier National Bank.

The Scandinavian-American Bank

Andrew Chilberg (1845-1934), an organizer of the Swedish-American Bank, was born in Sweden and grew up primarily in Iowa. In 1870 his family homesteaded in Washington Territory near LaConner, Skagit County. He came to Seattle from the homestead in 1875 to work in a grocery business with his brothers, Nelson and James. From 1879 until 1926 he served as consular representative in Seattle for Sweden and Norway, and during the 1880s he was a Seattle alderman, city treasurer, county assessor, and a member of the school board. Chilberg was appointed ticket agent for the Northern Pacific Railroad Company in 1885, and in 1892 he became the Swedish-American Bank’s first president and remained active in its operations until the bank closed in July 1921.

In 1897 the Scandinavian-American Bank moved to the Bank of Commerce Building. Andrew Chilberg was president, A. E. Johnson, of St. Paul, Minnesota, was first vice-president, K. C. Tvete of Seattle was second vice-president, and Axel H. Soelberg, also of Seattle, was cashier.

Andrew Chilberg is remembered today for sponsoring a large May festival in 1908 to support the establishment at the University of Washington of a Department of Scandinavian Languages and Literature, a goal that was fulfilled when the State Legislature authorized the department in 1909. In 1892 he owned the Stockholm Hotel at 1st Avenue and Bell Street, which housed a restaurant; the early Swedish Club; and the local Swedish newspaper, Svenska Pressen. His death at Swedish Hospital was reported in The Seattle Times on February 14,1934, and his funeral was held at Johnson & Brothers Mortuary on E Madison Street, whose owner, Sophie Johnson, was herself from Sweden.

John Edward Chilberg (1867-1954), Andrew’s nephew, built the Alaska Building, which was considered Seattle’s first steel-framed skyscraper. He became vice-president of the bank in March 1905 when A. H. Soelberg resigned and the bank moved to the Alaska Building. He went on to become a prime mover in Washington's first world's fair, the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition of 1909.

It seems likely that the third floor of the Bank of Commerce Building was added when the Scandinavian-American Bank moved out in 1905. The design of the third floor has been credited to architect Albert Wickersham, who came to Seattle in 1889 as supervising architect for the Denny Hotel. He started his own practice in 1892, and one of his first private commissions was the Dexter Horton Bank Building at 119 1st Avenue S (now the Maynard Building), located at the northwest corner of Commercial and Washington streets.

The State Bank of Seattle

Axel Herman Soelberg (b. 1869) emigrated from his homeland in Norway to Minneapolis in 1888, and then to Seattle in 1892. He worked as bookkeeper for the Swedish-American Bank, became the bank's cashier two years later, and in 1901, was appointed the bank's vice-president. In 1905 when the Swedish-American Bank moved to the Alaska Building, Soelberg chose to remain where he was and to create his own bank, the State Bank of Seattle, with Einar L. Grondahl as president and himself as vice-president and cashier.

During the winter of 1905, both Soelberg and Grondahl lived in the lavish Washington Hotel. Soelberg, his wife Olga Wickstrom Soelberg, and their children befriended Nellie Cornish (1876-1956), the founder of the Cornish School, and invited her to live with them. The music-loving Soelberg family and Grondahl remained friends with Cornish for decades, and the State Bank of Seattle remained her bank. It was Soelberg's young daughter, Louise, who nicknamed Cornish “Miss Aunt Nellie,” which remained her popular name throughout her years in Seattle.

In 1910 or 1911, the State Bank of Seattle moved across the street to the Mutual Life Building. It was the last of the three anchor-tenant banks to leave the Bank of Commerce (Yesler) Building.

A Slow Decline

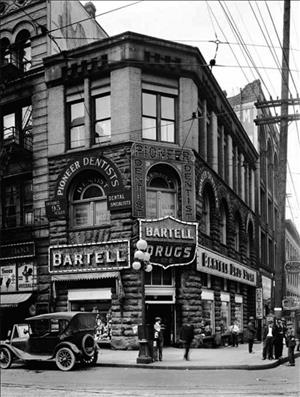

As banks started moving uptown, other enterprises with less cachet took their place. The Dinham-Strehlau Shoe Company, owned by H. Thomas Dinham and J. Andrew Strehlau, had expanded rapidly between 1st and 2nd avenues along Yesler Way, and by 1919 was also located in the Bank of Commerce Building. William H. Thompson's dental office, which later became Pioneer Dentists, was upstairs.

In 1928, when the Seattle Directory first published a reverse directory, the tenants of the Bank of Commerce Building were shown to be the Army Goods Trading Co. (Abe S. Mesher proprietor) and the Afro-American Club. The year 1928 was the last year the Afro-American Club had an address in the Seattle Directory. Beginning in 1916 it was listed as located in the rear of 110 Seneca and the secretary was Albert L. Duncanson who, with his wife Ophelia, lived at 2010 E James Street. In about 1925 the club had moved to 304 ½ James Street and the secretary was William Jones. The club moved to the Yesler Building in 1927.

Sam Israel and the Samis Foundation

The Bank of Commerce Building, along with the Schwabacher Building that abuts it on two sides, is one of the real-estate holdings acquired by Sam Israel (1899-1994) during his many years of purchasing properties in Seattle. Israel was born on the island of Rhodes in Greece, and came to Seattle in 1919 to work as a shoemaker. During World War II he secured a contract with the U.S. Army to repair combat boots and invested his earnings in real estate through his Samis Land Company.

When Sam Israel died in 1994, the company's holdings became the property of the Samis Foundation, which he had established in 1987. Today the foundation owns and manages the now-restored Bank of Commerce Building, among other properties. At Israel's direction, the goals of the Samis Foundation are "to enhance Jewish education in Washington State and to enhance the appreciation for Jewish culture and history in both Washington State and in Israel" (Samis Foundation).