On the stormy night of January 2, 1903, the Norwegian bark Prince Arthur is en route in ballast from Valparaiso, Chile, to Esquimalt, British Columbia, for lumber when the vessel strikes an offshore reef, 10 miles south of Cape Alava, on the sparsely inhabited north coast of the Olympic Peninsula, and breaks apart, throwing its 20-man crew into the turbulent sea. There are only two survivors. They, with the help of the local settlers and Indians, recover the bodies of 12 of the victims and bury them on the beach in shallow graves. A short while later, a delegation from the Norwegian community in Seattle will move the bodies to a common grave on the bluff overlooking the wreck site and will erect a granite obelisk, designated the Norwegian Monument, to honor the dead sailors. It is one of the many tragic events to occur on the Washington coast, an area known to mariners as the Graveyard of the Pacific.

Life on the Sea

The three-masted Norwegian bark Prince Arthur, formerly British bark Hoghton Tower, was built in Birkenhead, England, in 1869 for G. R. Clover and Company. The 1,600-ton, iron-hulled vessel was 240 feet in length and 40 feet across the beam. She was one of a fleet of ships owned by P. H. Roer of Christiania, Norway, used to haul lumber from the Pacific Northwest to ports around the world. The ship’s master was Hans Markussen, a thoroughly experienced, lifelong mariner, who had sailed the world with his wife and three small children aboard for three years. Markusson’s family left the ship in England in 1902 and returned to their home in Larvik, Norway, so the children could attend school.

On Friday, January 2, 1903, the

Prince Arthur

, with a crew of 20, was on the last leg of a 7,500-mile voyage from Valparaiso, Chile, to Esquimalt, British Columbia, for a load of lumber. In the nineteenth century, Valparaiso was an important layover port for ships traveling between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The

Prince Arthur

had been at sea for 50 days and had encountered mostly good weather. But thick weather set in along the coast of Oregon, with strong winds blowing from the southwest. The bark had been scudding with the wind for three days, without seeing land, forcing the crew to navigate entirely by dead reckoning (a method which uses compass courses and approximate distances sailed, to determine the ship’s position). Periodically, the quartermaster took soundings to determine their position relative to the coastline. Captain Markussen was unaware, however, that the heightening gale and strong ocean currents had driven the vessel inshore.

Alarm and the Battle to Save the Ship

At approximately 5:30 p.m., well after dark, the forward lookout warned of a faint light dead ahead. A light suddenly appearing off the bow was not good news. Initially Captain Markussen thought it might be the lightship marking the treacherous Umatilla Reef or the beacon on Tatoosh Island. But the storm had lifted the fog sufficiently for him to see the outline of the Olympic coast. Horrified, Captain Markussen immediately ordered the ship to come about and head for open water. But it was too late. The vessel struck a jagged reef, punching a hole in her metal hull. The Prince Arthur had inadvertently sailed into the maze of treacherous reefs and pinnacles lying north and east of Carroll Island and Jagged Island.

The tide was ebbing when the bark hit a reef off Kayostia Beach, some 10 miles south of Cape Alava. The crew hastened to make repairs to the Prince Arthur’s hull and the ship managed to break free from the first reef. Before she could escape into open water, a large wave lifted the bark onto another reef. The bow was now solidly upon the rocks while the stern lay toward the sea. Huge waves, driven by gale-force winds, mercilessly raked the ship from stem to stern.

The crew battled to save the ship, manning the bilge pumps, jettisoning equipment and supplies, as well as burning blue lights and launching distress flares to attract attention. But the worsening storm and powerful waves, together with the low tide, made escape impossible. The Prince Arthur stayed intact until midnight when an enormous wave swept the ship onto a third reef, causing irreparable damage to the hull. The surf relentlessly pounded the ship against the rocks, breaking the iron hull in two. The forward section sunk beneath the waves, leaving the aft section sitting upon the reef.

Meanwhile, the crew had donned life belts and clung to the railings or climbed into the rigging to avoid being carried overboard. But before long, the entire 20-man crew was swept into the sea and mountainous breakers battered the sections of the hull into pieces.

Surviving and Burying the Dead

Second Mate Christopher Schjodt Hansen, clinging to a piece of wreckage, immediately headed toward the shore. Twice, he found brief respite upon rocks, but realizing his predicament, plunged back into the water and resumed swimming. After struggling in the surf for over an hour, Hansen was finally washed ashore. Totally exhausted, he crawled up the beach and sought refuge behind a log. He could hear his shipmates in the surf, calling out for help, but was unable to provide any assistance. Eventually the cries ceased and Hansen, suffering from hypothermia and weak with fatigue, lapsed into unconsciousness.

At daybreak on Saturday, January 3, Hansen awoke and started walking along the beach. Except for some spars floating beyond the line of surf, the Prince Arthur was no longer visible from shore. He soon encountered sail-maker Knud Larsen, who had also washed ashore clinging to a piece of wreckage. The two men searched the strand for survivors, but found only a few battered corpses floating in tide pools amid the flotsam and jetsam. They dragged the bodies up the beach and laid them side-by-side behind a sand dune. Hansen had lost his boots, which he needed in order to survive, and took a pair off one of the dead sailors. The men climbed the bluff and headed inland, but soon realized they would become hopelessly lost. They reasoned that Indians were likely in the vicinity and followed the beach south. They found more of their dead shipmates lying on the rocky beach and dragged them above the high-tide line for safekeeping.

At about noon, Hansen and Larsen saw a column of smoke rising and before long came upon a clearing in the forest and a small log cabin. A man was on the beach, working on a small boat, who introduced himself as Iver J. Birkestol (1862-1933) from Norway. He and his brothers, Ole and Tron, had homesteads in the area and were happy to provide assistance to their fellow Norwegians. The two survivors were brought to Iver Birkestol’s seaside cabin and provided with food, clothing and a place to recuperate. It was undoubtedly light from this cabin the Prince Arthur had seen. Later Hansen and Larsen assisted the Birkestol brothers and several Indians in finding and burying the dead bodies.

Aftermath of Disaster

On Tuesday, January 6, 1903, news of the disaster reached Clallam Bay. It was brought out by mail courier over a 25-mile trail through the wilderness from Ozette. The next day, thanks to the wire service, the story was in newspapers throughout the country.

On Friday, January 9, the 145-foot passenger steamer Alice Gertrude, owned by the Puget Sound Navigation Company, delivered a letter to Captain Oscar Klocker, acting Norwegian Consul in Port Townsend, from Hansen with a detailed account of the wreck. Klocker immediately sent the letter on to Andrew Chilberg, the Norwegian Vice Consul in Seattle.

Meanwhile, Hansen and Larsen traveled north with a group of Indians to the Ozette Indian village at Cape Alava. The men spent the night at the village, then set out with another group of Indians in dugout canoes toward Neah Bay, arriving there on Saturday, January 10, 1903. The proprietor of the trading post took care of the men until the Alice Gertrude arrived and ferried them to Port Townsend. Captain Klocker and several newspaper reporters were on hand to meet Hansen and Larsen and obtained firsthand accounts of the disaster. Afterwards, the Alice Gertrud steamed to Seattle with the two survivors aboard.

Recovering Remains

At 11:00 a.m. on Sunday, January 11, 1903, the Norse Club of Seattle held a meeting in the Arcade Building, on 2nd Avenue between Union and University streets, and decided to send a delegation to the scene of the wreck. The members were determined not to let the bodies of their countrymen be buried on the beach in unmarked graves. The plan was to recover all the bodies, bring them to Seattle and hold an elaborate public funeral to honor the sailors, then bury them in one of the city cemeteries. Four men volunteered for the assignment: Captain John A. Johnson, master and owner of the schooner Pilot, Carl Sunde, president of Sunde and Erland Company (ship chandlers and sail makers), Lorntz W. Sandstrom, president of P. F. Nordby Fisherman’s Supplies, and mortician Charles F. Johnson, from the Johnson and Hamilton Funeral Home, whose duty it would be to determine if recovery was feasible.

On Sunday evening, the Norse Club delegation set sail aboard the Alice Gertrude for Neah Bay, arriving on Monday morning. They hired an Indian guide to take them as far as the Ozette River and set out Tuesday morning in wet and dreary winter weather. The trail through the wilderness was almost impassable, but the expedition slogged on. The group arrived at the Ozette River on Tuesday night, but was unable to cross the swollen stream in the dark and had to wait for daylight before continuing. At dawn, the party resumed their 30-mile trek to Kayostia Beach, arriving Wednesday night.

On Thursday morning, January 14, the delegation met the Birkestol brothers, who showed them where all the men had been buried. Altogether, 12 bodies had washed ashore and were interred in shallow graves along the beach. Johnson, the mortician, examined the remains and determined, due to advanced decomposition, it would be impossible to remove the corpses to Seattle. Fearful the next storm might carry the bodies back out to sea, the men set out to find an appropriate location for a permanent grave. They found an acceptable spot on a headland overlooking the sea. It was on Iver Birkestol’s claim, so a fellow Norwegian would be there to safeguard the grave site.

Meanwhile, the steam schooner Santa Barbara arrived off Kayostia Beach with Henry M. Thornton, a Seattle shipping agent, hired by the owners of the Prince Arthur to salvage the wreckage. What remained of the bark sat submerged under the water, a quarter mile off shore. “The wreck itself is complete,” Thornton reported. “The vessel's foremast went by the board and the after mast and main mast followed. It was following the loss of the three sticks that the bark went to pieces. She had split down the middle along the keel and it was just like opening a book, the sides of the craft clinging to the keel. Nothing hardly is visible and it would not pay to even try and pick up the old iron” (The Seattle Times). Thornton returned to Seattle with a message from the committee for Hans P. Rude, president of the Norse Club, that the bodies could not be removed and would be buried nearby in a common grave.

The men cleared a place in the underbrush and then dug a burial plot 14-feet square. The bodies had been stashed in sandy graves along more than two miles of the coastline. For three days, the delegation, with the help of the Birkestol brothers and two local settlers, Chris Christiansen and Fred Moody, dug up the remains and carried them on makeshift stretchers to the top of the bluff. They lined the grave with canvas from the Prince Arthur’s sails, found along the shore, then shrouded each sailor in canvas. When all the bodies had been laid in the grave, side by side, pieces of the bark’s planking were carted up the bluff, placed over them in a double row, and then mounded with dirt. The delegation found a carved oak door frame on the beach, which they placed at the head grave, facing the ocean.

Honoring the Dead

The delegation returned to Seattle by steamer on Tuesday, January 20, 1903. That evening Louis Sandstrom gave a speech to the members of the Norse Club, recounting the details of their harrowing journey. He said in summation: “I have the tattered ship’s flag as a memento of the trip and each of us has a bit of brass work torn from the wreckage of the vessel. It is not a trip I would care to take again” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer). The club members pledged to raise enough money from the Norwegian community to create a proper monument commemorating the tragedy, and acquire title to the plot of land where the sailors were buried from Iver Birkestol.

In Seattle, meanwhile, Hansen and Larsen were enjoying the largess of the Norwegian community. When the men had recovered sufficiently, the Norwegian consul put them on a train to New York where they boarded a ship bound for Norway.

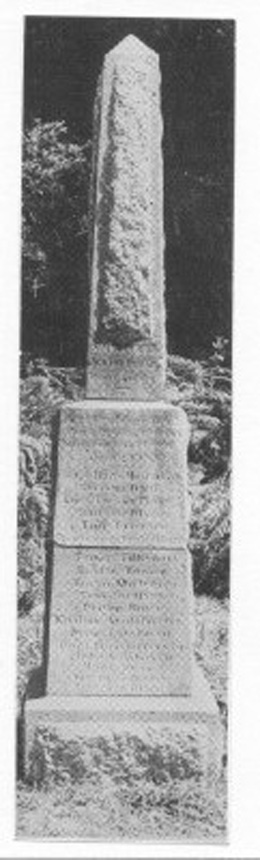

After several months, the Puget Sound Marble and Granite Company completed the Norse Club’s unpretentious monument. Made of granite, it was created in four sections and stands approximately 10 feet tall. The bottom section is a plain one-foot tall by two-and-a-half-foot square block, supporting two tapered middle sections on which is chiseled the simple epitaph, “Here lies the crew of bark Prince Arthur of Norway foundered January 2, 1903,” and the names of the dead sailors (several of whom were Danish). The top section is a five-foot-tall obelisk, bearing the names of the two survivors.

In 1904, the Norse Club of Seattle erected the monument at the grave site. Getting it to the bluff above Kayostia Beach wasn’t easy. A ship carried the four pieces from Seattle and they were brought ashore at an old placer-mine supply landing near Sand Point, south of Cape Alava. The stone blocks were lugged south along the shoreline to Iver Birkestol’s homestead. After the monument was reassembled at the grave, representatives from Seattle’s Norwegian community held a dedication ceremony.

Maintaining a Monument in the Rain Forest

In 1906, Iver and Ole Birkestol (1866-1930) sold their homesteads in Clallam County and bought a 145-acre dairy farm on Norman Road just outside of Stanwood in Snohomish County. Tron Birkestol moved his family to Lake Ozette and homesteaded there. Iver retained ownership of 10 acres of land surrounding the grave site, the monument, and his log cabin. He died in 1933, but his family continued to pay the taxes on the acreage until President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) signed the act establishing Olympic National Park in 1938. In 1940, President Roosevelt authorized the Public Works Administration to acquire a long strip of the Washington coastline for inclusion into the park, which included Iver Birkestol’s homestead. The coastal strip wasn’t officially added to the park, however, until 1953. The National Park Service indifferently designated the grave site as the Swedish Memorial.

Meantime, the monument was being maintained by members of Puget Sound’s Norwegian community, who regularly made pilgrimages to the monument to clear away the fast-growing underbrush, remove destructive moss from the granite stonework, and refresh inscriptions with black paint. Without their continued efforts, the grave site and monument would have been enveloped by the rain forest within a year.

Preserving the Memory

In 1955, the Norwegian Commercial Club of Seattle (formerly the Norse Club), the Norwegian-American Historical Association and the Port Angeles Chamber of Commerce organized to establish a memorial park above the site where the Prince Arthur foundered, incorporating the grave site and monument. They formed the Bark Prince Arthur of Norway Monument Committee, co-chaired by Norwegian community activists Commander Carl M. Moe, USNR (retired) and Robert A. Moen. In addition to a memorial park, the committee wanted the National Park Service to correct their maps and trail markers to read Norwegian Memorial instead of Swedish Memorial. To make the site accessible, the committee also proposed building a new coast highway, financed by state and federal funds, extending from Neah Bay to Grays Harbor.

In 1956, Senator Henry M. Jackson (1912-1983) persuaded the National Park Service to correct its maps and trail markers to read Norwegian Monument, but the memorial park and coast highway proposals were rejected. The monument was considered an important historic artifact, and the grave site, on federal land, was under the protection the federal government. The issue of building a highway through the park became moot in September 1964 when President Lynden B. Johnson (1908-1973) signed the Wilderness Act, prohibiting development and motorized vehicles. Since then, nearly 96 percent of the Olympic National Park’s 922,651 acres has been designated as wilderness, including more than 60 miles of Washington’s coastline.

A Son's Visit and Those Who Care

On Tuesday, September 25, 1973, Captain Hans Markussen’s son Viggo, age 79, (1894-1984) and his wife, Astrud, visited his father’s grave for the first time. Viggo came to America in 1923 to just stay for a year, but then decided to immigrate. Donald A. Stubb, a third-generation Norwegian, working for ITT Rayonier as an inventory forester, learned about Markussen through an article in a Norwegian language newspaper. He contacted the couple in Toms River, New Jersey, sent them pictures of the monument and invited them to visit. With permission from the National Park Service, Stubb arranged for the Markussens, accompanied by Commander Moe, to be flown to the remote location in a company helicopter. While at the monument two members of the Norwegian Commercial Club, Thor Hurlen and Allen Anderson, arrived to perform maintenance. “It’s very touching how many people in this area have taken and interest in the monument for father and his crew,” Markussen said (The Seattle Times).

Today, the Norwegian Monument is still perched on the bluff above Kayostia Beach. Since Olympic National Park is a designated wilderness area, it is only accessible via the North Coast Beach Trail. Hikers can reach the trail from either the Ozette Ranger Station, at the north end of Lake Ozette, or from the Rialto Beach Ranger Station near La Push. The hike between the ranger stations is 17 miles and, depending on tide and weather, takes at least nine hours one way. The Norwegian Monument is considered the half-way point. Although it is possible to make the trek in one day, most backpackers allow two days or more. The National Park Service requires a back-country permit to hike in the Olympic wilderness, available at the park’s ranger stations.

Victims

-

Andersen, Egil, able seaman

-

Andersen, Anders, bosun's mate

-

Balza, Phillip D., ordinary seaman

Bernsten, Emil, ordinary seaman -

Christoffersen, Carl, apprentice seaman

-

Dahl, Herman, first mate

-

Falkedahl, Frantz, ordinary seaman

-

Fjaere, Lars Larsen, ordinary seaman

-

Fredericksen, Ferdinand, ordinary seaman

-

Hansen, Haldor, ordinary seaman

-

Johnsen, Anders, ordinary seaman

-

Kristoffersen, Kristian, apprentice seaman

-

Lovskoven, Oscar, steward

-

Markussen, Hans, captain

-

Mortensen, Gustav, ordinary seaman

-

Olsen, Gotfred, ordinary seaman

-

Olsen, Gutbrand, apprentice seaman

-

Olsen, Hans, ordinary seaman

Survivors

-

Hansen, Christopher Schjodt, second mate

-

Larsen, Knud, sail maker/carpenter