On July 7, 1811, Canadian explorer David Thompson (1770-1857) records the first written description of the Sinkayuse Indians and the landscape along the Columbia River from the mouth of the Wenatchee River (near present-day Wenatchee) to Crab Creek, in present-day Chelan, Douglas, and Kittitas counties. Thompson and his crew are on a historic voyage down the Columbia to determine whether the river is navigable to the sea and whether it will provide a viable route for the fur trade.

July 7: Wenatchee River to Crab Creek

"July 7th. Sunday. A fine day but cloudy Morng. At 7 Am set off .. to the SW see high rocky Mountains bending to the So[uthwar]d" (Nisbet, MME, 107). The Nor’Westers had been on the river for only a few miles when they passed the mouth of the Wenatchee River (near the present-day city of that name) and soon afterward pulled ashore to smoke with two horsemen. A short distance downstream, they landed at a substantial village (near present-day Rock Island Dam). The residents, whom Thompson called the Sin kowarsin (Sinkayuse), greeted the newcomers by dancing inside two long mat lodges. The surveyor invited them to smoke, but at first only five headmen would join him; eventually the rest of the camp gathered around, and Thompson estimated that there were 120 males in all.

"A very respectable old Man sat down by me, thankful to see us & smoke of our Tobacco before he died -- he after felt my Shoes & Legs gently as if to know whether I was like themselves" (Nisbet, MME, 107).

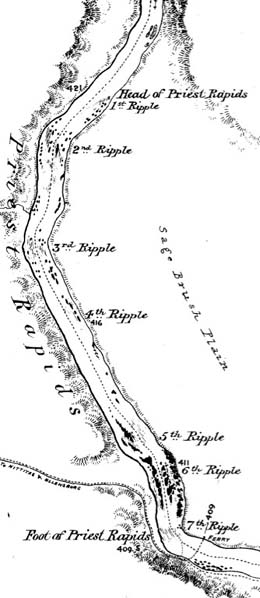

Thompson paced off the length of two longhouses -- one was 80 yards long, the other 20. Someone at the gathering impressed Thompson as a religious figure, for he labeled the Sinkayuse encampment as "the Priest’s Village" in a survey book.

"They put down their little presents of Berries, Roots &c, & then continually kept blessing us and wishing us all manner of good for visiting them, with clapping their Hands and extending them to the Skies. When any of us approached their Ranks they expressed their good will & thanks with outstretched arms & words followed by a strong whistling aspiration of the Breath" (Belyea 149).

The Sinkayuse, whose main village at the time of contact lay at the mouth of Rock Island Creek, ranged throughout the area encompassed by the Big Bend of the Columbia. They informed Thompson that they also hunted deer, sheep, and mountain goats in the foothills of the Cascades, and he noted the excellent blankets they made from the hides of the goats, His attention was also caught by the shells the people wore in their noses and by a few buffalo robes, which he assumed they had obtained through trade. In fact, after horses arrived in their lands, the Sinkayuse and several neighboring bands often traveled east to hunt bison near the headwaters of the Missouri River (Miller, 266).

The Sinyakuse village marked the edge of the tribes that spoke Interior Salish, and while the furmen and Sinkayuse parleyed at Rock Island, a visiting chief from a different tribe approached Thompson and offered to interpret for him on the way downstream, where an entirely different language was spoken. The surveyor "gladly accepted & we embarked him, his Wife & Baggage" (Nisbet, MME, 108).

After walking along the shore while his men ran Rock Island Rapids fully loaded, Thompson climbed back aboard and floated past "steep fluted Rocks" at the mouth of Moses Coulee and "a vast wall of Rock" at Lodgestick Bluffs. The Sinkayuse had given them several salmon, and in mid-afternoon the furmen stopped to cook the fish at a secluded spot, because "while with the Indians our whole time is occupied in talking and smoking with them." Near their picnic site, the surveyor noted a depression where the ground had been hollowed away about a foot deep; the interpreter explained that this was the foundation for one of the pit houses where the Sinkayuse lived during the winter season. A roof framed of driftwood logs was covered with mats and brush, then plastered with clay for waterproofing (Miller 259).

That evening the Nor’Westers camped near the mouth of Crab Creek (just below the present town of Beverly in Grant County). The night proved fitful, with mosquitoes and a high wind.