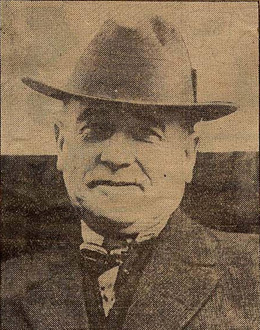

James "Jimmie" Durkin gained notoriety in the Inland Empire of Eastern Washington as Spokane's legendary liquor tycoon. Wild tales abound regarding his outlandish exploits and stunts, but beyond becoming one of the town's most successful businessmen and an early millionaire, Durkin earned a well-deserved reputation as a thinking man. Indeed, locals and area newspapers routinely referred to the one-time gubernatorial candidate as no less than "Spokane's Main Avenue philosopher."

A Daredevil "Irishman"

Born to Irish parents in Wasall, England, young Jimmie Durkin and his family (including 13 siblings) arrived in America as immigrants in 1868. After briefly settling in Decatur, Illinois, and then in Liberty, Missouri, the daredevil 9 year old ran away from home, and soon wound up in Brooklyn, New York, where he lived with an uncle and raised funds by selling the The Brooklyn Eagle newspaper. By 1872 he was working in a bar. Eventually Durkin moved on to learning the wholesale liquor business in Perham, Minnesota, where on August 8, 1882, he married Margaret Daily (and they went on to have three sons and two daughters).

Years passed and in 1886 Durkin headed out west to Washington Territory. He first arrived in Colville, a bustling little town that was experiencing a boom due to the silver rush at Stevens County's Old Dominion Mine. Though the hamlet already boasted nine active saloons, Durkin couldn't find a job. He poked around a bit and realized that each of those bars was unwisely overpaying wagon-train companies for freight deliveries from Spokane. After some quick calculations he realized that by shipping booze in by the barrel (instead of the jug), he could cuts costs by 50 percent. And thus, with the $2,500 he'd arrived with, Durkin opened Colville's 10th liquor outpost -- and within a few years his nest-egg had grown into a small fortune totaling $65,000.

Durkin's Bar

At some point his young family apparently rejoined him, but times became harder. The first disruption came on August 4th with the Great Fire of 1889, which saw Spokane nearly destroyed after a Railroad Avenue saloon's kitchen erupted into flames. Then there was the economic Panic of 1893, which frightened everybody and hurt most businesses. Meanwhile, a new mining boom broke out in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, with Spokane becoming a great beneficiary of all that nearby activity. The draw of the big city attracted Durkin and in the spring of 1897 he relocated there.

Situated in a downtown storefront on the northwest corner of Sprague Avenue and Mill Street (today's Wall Street), Durkin's Bar began retailing liquor, and his adjacent bar served fine alcoholic beverages, including Dewar's Scotch, Seagram's Canadian Whiskey, Old Crow and Hermitage brand Kentucky whiskies, Spanish sherries, and Ireland's beloved Bass Ale and Guinness Stout, along with quality cigars. Under the supervision of his employee -- a dignified white-haired gentleman called The Colonel -- drunks and their boisterous language were not tolerated and bartenders were forbidden to imbibe while on duty. So Durkin's Bar not only offered better-priced drinks to its clientele, it also earned a reputation as a relatively respectable joint.

Jimmie Durkin Rocks!

But Durkin had a plan for bypassing the competition represented by Spokane's other 120 saloons -- and it amounted to an unceasing advertising blitz. His most famous brainstorm occurred while he was riding a stagecoach into Spokane. Along the way Durkin had noticed plenty of large boulders lining the route, and he soon had a local Swedish sign-painter applying a "Jimmie Durkin's Fine Wines and Liquor" sign on nearly every stone, tree, ledge, or other bare surface around. That commercial graffiti reportedly annoyed some locals and the tale is told about the day that a miner swaggered into the bar, dropped a chunk of granite on Durkin's desk and said "See anything peculiar about that rock, Jimmy?" Durkin replied, "No. I can't say that I do." "Well," came the stranger's retort, that's because "I found that rock 4,000 feet below the surface and it's the only one in this part of the country without your name on it!" (Federal Writers' Project).

If mildly controversial, those painted advertisements merely proved to be Durkin's opening act of audacious promotion. Among the many popular tales surrounding Durkin and his outlandishly fun-loving ways is the one regarding housecats. Asked by a pal why he invested so much capital in his advertising campaigns, he responded: "It is the very life of trade. I will wager I can place an advertisement in The Spokesman-Review offering to buy cats, and by nightfall I will have a basement full." Once that bet was accepted, Durkin promptly placed his "cats wanted" ad and when his buddy dropped by the following evening he was astounded to see the power of advertising in action: Durkin was suddenly the proud owner of a teeming menagerie of scores and scores of cats that the public had delivered.

Additional means of promoting his enterprises -- eventually Durkin had three shops (at 702 Sprague Avenue, 121 Howard Street, and 415 W Main Avenue) -- included offering his customers a daily free lunch and entertaining them with several cages of singing canaries. Beyond that he took to retailing wines and whiskies in custom-made stoneware jugs of various sizes and shapes -- each bearing the logo and street addresses of his firms. Among the most notable of these units were the large dark-brown glazed "drum top" jug, and an oddly shaped brown-glass "megaphone" bottle. Though considered worthies by antique collectors for many decades now, even back in the day, old Durkin had a prescient quip about the containers: "Durkin's bottles are good when they are full, that's more than you can say for the fella that gets full emptying them" (Kalez).

Temperance and a Good Temper

Well before the prohibition of alcohol sales in Washington became law on December 31, 1915 -- five years before Prohibition went into effect nationally between 1920 and 1933 -- a temperance movement had been simmering among moralistic activists across the land. But along the way, Durkin faced such issues with his typical forthrightness and good humor.

One celebrated example: Around June 1907, the good Reverend E. H. Braden -- pastor of a local Baptist Church (probably the Calvary Baptist Church at 426 E 3rd Avenue) -- took offence at Durkin's window display, which at the time featured a flock of stuffed crows intended to promote Old Crow Whiskey. When an area newspaper noted Braden's fulminations from the pulpit about how such advertising failed to depict the evil downside of liquor trafficking -- and that he'd stated a desire to have a chance to mount his own display at Durkin's -- the booze magnate slyly took him up on the idea. Durkin even graciously told him that "you can use all of my windows for any liquor displays you want. You can use anything you want, advertise anything you want, and I will not interfere. Also I will pay for everything. You can depend on me: I'm a man of my word" (Kalez).

Braden -- who was ably assisted by John Matthiesen (the advertising manager for Spokane's stationery shop, the John W. Graham Company) -- proceeded to mount an ambitious new eight-window tableau at Durkin's. The displays were certainly eye-catching, some might say a bit morbid and depressing. They included a mock-up of the "dream home" of a happy newlywed couple that included a full-sized piano and other genteel furnishings. The adjacent window hammered its anti-alcohol theme home with another view of that household, this time showing the bride, along with shabbily dressed kids, sweating over a laundry washboard. The message of alcohol's ability to destroy lives and dreams was powerful, but Durkin's standing in the community was resilient and some locals would forever after jokingly refer to their washboards as "Durkin's pianos."

The new displays drew considerable attention over the weeks, enough to make The Spokesman-Review scoff, calling the incident a "gigantic publicity stunt," which it certainly was. But that was Durkin's genius -- and business at Durkin's Bar increased dramatically. Enjoying the media coverage, and apparently all caught up in the hoopla, Durkin even went so far as to run as a Democratic candidate for governor in the 1908 election. He received 4,398 votes, but lost during the primary.

Meanwhile, Reverend Braden famously conceded that at the very least, "Jimmie Durkin is a man of his word." And though Durkin would proudly use that phrase as his motto ever after, the wily businessman always managed to get in the last word: By July 1907 he was placing display ads in newspapers that stated: "Visiting Baptists Are Invited to Inspect the Only Liquor Store in America Whose Windows Were Decorated by a Baptist Minister."

The other six Baptist-designed windows contained a variety of displays generally featuring "pictures of ragged women abandoned by hard-drinking men and with statistics about the ill-effects of liquor. One window contained a pile of sad, worn-out shoes, next to a gleaming pair of patent-leather shoes with gaiters, labeled, 'The shoes of the saloon-keeper'" (Kershner). However, even after Braden and Matthiesen's display was eventually replaced, Durkin reportedly respected its main message enough to place a sympathetic sign of his own in the bar: "If your kids need shoes, don't buy booze" (Biegler).

Prohibition Era

Although Prohibition directly threatened Durkin's business interests, he reacted calmly and resolved to make the best of the situation. On July 31, 1915, he told The Spokesman-Review: "We finish here now. Some day, it is my personal opinion, there will be a reversal of the prohibition policy. In any case, I and my organization will give the law the strictest obedience."

Durkin faced the coming shift in legal status by informing his suppliers back east that he would be ordering no new liquor, by wholesaling out his current stock to various buyers, and by closing down two storefronts. The third business (at 415 W Main) was sold to a duo who opened a men's card-room and billiard hall called Stewart and Ulrich -- a partnership that later broke up. Durkin resurfaced after the repeal of Prohibition in 1933 and recast the card-room as the Durkin and Ulrich Saloon.

"The Main Avenue Philosopher"

Durkin was a famously outspoken individualist and life-long Democrat in a city not noted for progressive politics. He spent most days holding court at his small wooden desk, doling out witty opinions on many topics. During the 1925 Scopes "Monkey Trial" over teaching the theory of evolution in schools, he fired off a congratulatory telegram to the beleaguered defense attorney, Clarence Darrow, saluting his commitment to "freedom of thought and education." Durkin himself reflected a remarkably open mind for his times. Raised within the Catholic faith, he eventually came to publicly espouse an atheistic philosophy.

Durkin became less active over time, although he did once make a three-month trip to his ancestral home of Ireland (and England and Scotland). As comfortable millionaires, he (with a new set of solid-gold dentures) and his wife, Margaret, (and those canaries) were quite happy in their beautiful 1910 Craftsman-styled home located in the Cliff/Cannon neighborhood of Spokane’s South Hill at 930 S Lincoln Street. Interestingly, on July 10, 2006, the "Jimmie and Margaret Durkin House" (and its circa 1915 garage addition) were designated as historic landmarks with the City-County of Spokane Historic Preservation Office due to their being "excellent examples of the American Arts & Crafts tradition as expressed in the Craftsman style. The house was designed by the Ballard Plannary Company, a prominent Spokane architectural firm" (historicspokane.org).

Last Words

Durkin fell ill and on July 8, 1934, the remarkable Spokane character passed away at Sacred Heart Hospital (101 W 8th Avenue). He was buried on July 11 at the Greenwood Cemetery (211 N Government Way). But Jimmie Durkin once again got in the final word. Two deathbed quotes have been attributed to him. When asked if he wished to renounce atheism in favor of the Catholic faith of his youth, he stated: "As I live, so I die, for any man who does otherwise is not a man" (Kershner). The second was the one he arranged to have engraved as the epigraph on his headstone: Jimmie Durkin / Born 1859 Died 1934 / The minister said, "A man of his word."

In 1935 The Spokesman-Review looked back, noting that: "Jimmie Durkin is dead but everybody who knew the old man has tales to tell of his individualism. He belonged to the vanishing race of individualists, men who developed in original molds and not in the machine standardization of today. He was an Irishman who dared to be himself."