Walla Walla University, located in College Place, Walla Walla County, was founded as Walla Walla College in 1892. The school was established by the Seventh-day Adventist Church to provide regional church members with an education that was supportive of the denomination's mission. Initially a pre-collegiate Bible school offering courses mostly at the primary and secondary levels, in the early twentieth century, Walla Walla College evolved into a denominationally oriented liberal arts college. During the latter half of the twentieth century, the school grew significantly and started a number of successful professional programs. In 2007, the school was renamed Walla Walla University to reflect its status as both an undergraduate and professional school. In addition to the programs offered on its campus in College Place, the university operates a School of Nursing in Portland, Oregon, a marine station near Anacortes, Washington, and a graduate social work program in Missoula and Billings, Montana.

The Advent of Adventism

The Seventh-day Adventist Church emerged out of an early nineteenth-century apocalyptic movement. After an intense period of Bible study, William Miller (1782-1849) concluded that Christ’s second advent would occur in 1843 or 1844. Miller convinced others of his views and through pulpits, print, and camp meetings the Millerite message spread. Miller’s dates passed, but another date, October 22, 1844, was predicted, and thousands eagerly awaited the return of Jesus Christ. The anticipated last day passed and belief in an imminent advent fragmented: Many abandoned their hope in it; some believed that they had been wrong about the date; some believed that Christ had actually come, but in a spiritual sense; and some believed that the date was correct but that another kind of coming had occurred.

This last group, which eventually developed into Seventh-day Adventism, believed that Christ had entered a new part of the heavenly sanctuary and begun the final phase of his saving ministry. During the 1840s, this group developed doctrinally and settled on such distinctive beliefs as Saturday Sabbath observance and the continuing contributions of prophets, particularly of Ellen White (1827-1915). A period of organizational development followed, and in the early 1860s Seventh-day Adventists established a publishing association, local conferences, and a general conference. The Adventists also developed an interest in lifestyle issues and health reform, which led to the establishment of a health institute in 1866. An interest in education followed, which led to the start of the denomination’s first school in Battle Creek, Michigan, in 1872.

The pattern for the development of the denomination became a pattern for Adventist missions at home and abroad: the establishment of a small population base, a publishing enterprise, a sanitarium, and an academy or college. After Seventh-day Adventists began settling in the Pacific Northwest, it was not long before Adventist institutions began appearing there as well.

Adventists in Walla Walla

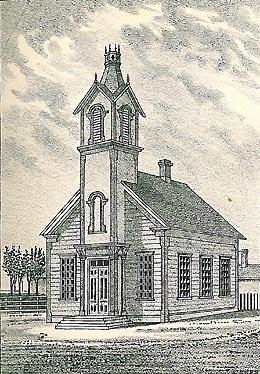

By the early 1870s, a small group of Adventists had settled in the Walla Walla Valley. They formed the First Seventh-day Adventist Church of Walla Walla, and in 1874 a minister arrived to help them expand the church through a series of tent meetings. A building for the church -- the first Seventh-day Adventist Church building in the Northwest -- was erected in 1875. In 1877, a Northwest conference was organized and held its first meeting in Walla Walla. Churches admitted to the conference included the Walla Walla church with 61 members and nearby churches in Milton, Oregon, and Dayton, Washington, with 24 members and 19 members respectively.

The church in Walla Walla attempted to start a school in the 1880s, but it was the church in Milton that succeeded in establishing an academy in 1887. In 1890, as Adventists began to expand their educational programs at all levels, the denomination’s educational secretary, William Warren Prescott (1855-1944), visited the Northwest. At that time, there were about 1,500 Adventists in the Northwest. With the support of Ellen White, Prescott advocated for the consolidation of the two existing Northwest Adventist schools, Milton Academy and another academy in Portland, into one large and centrally located institution. Milton was considered as a possible site, but then Walla Walla Mayor Nelson G. Blalock (1836-1913) donated 40 acres of land for a school a few miles west of Walla Walla.

In 1891, denominational leaders resolved to locate their Northwest school on Blalock’s land and made a 25-year commitment to the location. From the citizens of Walla Walla and the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, the school received initial support of about $60,000. Adjacent land was acquired and then sold off to migrating Adventists. Construction of a building began in early 1892, and the community around the school was platted and named College Place (incorporated as a municipality in 1945). College planners quickly formed an administration, faculty, and curriculum. Prescott, who was also president of Battle Creek College in Michigan (where he lived) and Union College in Nebraska, was selected as the first president of the college.

Becoming a College

On December 7, 1892, Walla Walla College opened. One of the opening distinctives of the school was its menu: it adopted the practice of vegetarianism, a health reform endorsed by Ellen White but at that time not broadly adopted within the denomination. The school’s impressive four-story building was not quite finished on opening day, but the college and local community assembled in the basement for a convocation service. Registration followed and by the end of the day 101 students had registered for primary, secondary, and basic college courses. More students enrolled, but tuition and gifts barely covered the college’s operating expenses. By the end of its first year, the college had run out of money and was unable to pay salaries.

Things worsened as the country entered a severe depression and after an unseasonal rainfall destroyed Northwest crops in the summer of 1893. Enrollment dropped and the school’s debt increased. In addition, some aspects of Adventist theology challenged the sustainability of the school. Since Christ’s return was believed to be imminent, many were ambivalent about taking the time off to go to college and opted for one-year programs. And no effort was made to build an endowment for the school. But with the support of the national General Conference, the school managed to remain open.

Edward A. Sutherland (1865-1955), an administrator at Walla Walla College since its opening, became the school’s president in 1894. Under the influence of Ellen White, Sutherland replaced the study of the classics with the Bible and emphasized practical studies that could be completed within a short period of time. The school also began to emphasize manual work, including food production and preparation, printing, farming, dressmaking, and basket weaving. This manual work generated some income for the college and evolved into vocational training, which provided students with marketable skills. These curricular changes facilitated the training of ministers, missionaries, church school teachers, nurses, bookkeepers, and stenographers.

Sutherland was such a successful leader that he was transferred to the presidency of Battle Creek College in 1897. During the next nine years, Walla Walla College had six presidents -- including Sutherland’s 22-year-old brother, who resigned after two years to prospect for gold in Alaska -- each of whom struggled to stabilize the academic mission and finances of the school. In 1905, Marion Ernest Cady (1866-1948) became the school’s eighth president and the school began spending its way out of debt and offering courses beyond the junior college level. In 1909, the same year in which the school dedicated a new building for the elementary school, the college awarded its first bachelor’s degree.

Development of an Adventist College

After 1909, Walla Walla College began to realize its Adventist vision of cultivating mind, body, and spirit by exposing students to a biblical curriculum, offering vocational training through college industries, and promoting spiritual culture. Ernest Clinton Kellogg (d. 1956), who became president in 1911, strengthened the college by further distinguishing it from the academy, making it possible for faculty to develop professionally, and fostering school spirit among faculty and students. He devised a motto for the school -- “The School that Educates for Life” -- and a seal: an equilateral triangle representing the trinity of mental, physical, and spiritual education.

In 1915, Kellogg wrote: “We are living in the age of increase of knowledge. ... During the past century the educational horizon has receded rapidly before an onward and accelerated march of observation, experimentation, and discovery. ... Not only is a liberal education necessary, but careful and thorough instruction in the doctrines as held by the denomination is imperative.” This statement appeared in the school’s first yearbook, The Western Collegian, which listed 24 faculty members and pictured more than 100 students. The library held 1,500 mostly new volumes and subscribed to denominational periodicals.

Student groups included literary societies, for cultivating oratorical skills; a Missionary Volunteer Society, which distributed religious literature, helped the sick and needy, and worked with local Italian, Chinese, and penitentiary populations; a Foreign Mission Band, which studied mission work abroad; a choral group and an orchestra; a female exercise club; and the Collegiate Association, which encouraged students to complete their course of study and promoted the college in the Northwest. Absent from the list of student activities were sports, about which Adventists were ambivalent. Tennis, which lacked the violence and team rivalry associated with other collegiate sports, was allowed. Students raised money for the first gymnasium on campus, which opened in 1917, and in 1922 basketball was permitted.

To sustain their educational ambitions, by the 1920s Adventist were seeking accreditation and changing their schools to be more like other American colleges. Walla Walla College’s three-year teacher-training program was validated by the state in 1923 and its basic collegiate program was validated in 1924. This success met with some denominational opposition, and in 1925 the school was reoriented toward its earlier sectarian character: Textbooks were carefully selected, the library collection was reviewed, faculty study leaves were canceled, and the school suspended its application for accreditation. But the denomination wanted its graduates to be able to enroll in graduate programs and to be employable outside the denomination, so the college eventually resumed making changes recommended by regional accreditors. Faculty members began obtaining Ph.D.s and more were hired who already held them. When it was accredited in 1935, Walla Walla College -- independent of the academy, which at that time became separate from the college -- was the largest Adventist college.

War Years

and After

After obtaining accreditation, tensions between secular and denominational standards persisted. In 1938, denominational leaders and the Walla Walla College Board purged the theology faculty of heterodox thinkers and obtained the resignation of President William Martin Landeen (1891-1982). To replace him, the board selected George Winfield Bowers (1895-1986), who had come to Walla Walla in 1924 to head the chemistry and biology departments. Bower repaired damaged relationships on campus and between the school and church, but the controversy, which had significantly disrupted programs and morale, was soon eclipsed by World War II.

Although not a pacifist denomination, since the 1860s Adventists had sought ways for its member to serve without violating the commandment “Thou shalt not kill.” In 1939, Walla Walla College started the Medical Cadet Corps, a program that taught military protocol, procedures for Sabbath-keeping while serving, and different draft status options. A similar program, the Medical Cadette Corps, began in 1942 to train women in first aid and military protocol.

Like other colleges after the war, Walla Walla College experienced a post-war enrollment boom funded by the GI Bill: In the fall of 1944, enrollment had been 493; in 1946, it was more than a thousand. To accommodate post-war enrollment levels, the college added new administrative positions, doubled the size of its faculty in five years, and accelerated the professional development of its faculty. Through new construction and renovation, the college added a number of buildings to its campus in just a few years. Additional building programs followed into the 1970s, which were sustained through increased tuition income and support from local conferences.

In addition to increased access, growth in higher education after World War II was also characterized by new professional opportunities in technology and the sciences. Walla Walla College, which had initially focused on practical training for church work, was well-positioned to develop programs for those eager to acquire professional training outside of the traditional arts and sciences and for careers outside of the church. In the late 1940s, the college developed specialized programs in nursing, engineering, and marine biology. The college’s engineering program, begun in 1947 and fully accredited in 1971, became one of the most popular programs at the college and one of the most prestigious academic programs within the denomination’s educational system.

Changing Times

In the 1960s, student activism and civil rights had an impact on the nature of Walla Walla College. The college’s long-standing parietal rules, regulating appearance, attire, and social behavior -- especially that of female students -- were challenged and dress codes were revised. The college began recruiting and providing scholarships to black students, who had previously been directed to a traditionally black Adventist school, Oakwood College in Huntsville, Alabama. In the 1970s, the college dispensed with its practice of paying employees based on gender or family status.

The last of the baby-boom generation passed through American colleges in the 1970s, and Walla Walla College reached the end of a sustained period of growth. As an income-dependent institution, the college had to borrow, fund its growing debt, and make cuts to budgets for staff, the library, and equipment. The college spun off its industries into independent corporations. In 1987, five years before it reached its centennial, the college launched its first endowment campaign. That same year, it began a graduate social work program.

With a broader base of financial support, from both private and public organizations, Walla Walla College continued to strengthen its programs. Because of the range of its professional graduate programs, in 2007 Walla Walla College was renamed Walla Walla University. At that time the school had more than 200 full-time faculty members and more than 1,800 students enrolled in liberal arts, professional, and technical programs.