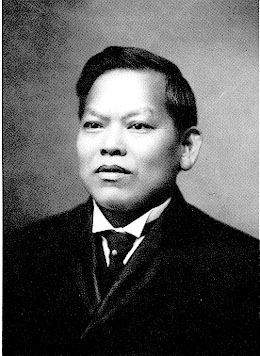

Goon Dip was a phenomenon -- a visionary and wealthy entrepreneur, public servant, philanthropist, and the most influential Chinese in the Pacific Coast during the early years of the twentieth century. He had some luck, which he acknowledged and honored, but he also had to breach the virulent anti-Chinese wall of the times to attain success. And he did it with a high level of civility and compassion. One obituary eulogized: “He brought the innate courtesy, the kindly philosophy, the ‘do unto others’ doctrine common to all faiths into his daily life ... "(Seattle Daily Times).

From China to America

Goon Dip was born, by most accounts, in 1862 in the village of Seung Gok, Guangdong Province, China, to Goon Feng Shew and Chin Shee. Various sources differ on the exact date. In 1876, at age 14, driven by dreams of prosperity in the United States -- the “Gold Mountain” – he arrived in Portland, Oregon, where members of the Goon clan already had settled. With about 700 residents, Portland’s was the third-largest Chinese community on the Pacific Coast, behind San Francisco and Tacoma. Goon Dip worked as a laborer for an “uncle,” Goon Sing -- not really an uncle, but from the same village in China. Anti-Chinese sentiment, already ominous, was growing, however, and “after a brief stay of a few years,” the Goon clan decided he should return to China, for safety (Jue and Jue, p. 42).

Chinese men had flocked to the United States in the 1860s and 1870s to dig for gold and help built the transcontinental railroads. They were welcome briefly to build the railroads, but when the gold ran out and the railroads were completed, thousands of Chinese men were thrown on the job market, just in time for the Long Depression. The slump lasted from 1873 until 1879, and the economy remained moribund for a long time after. The competition for jobs exacerbated whatever resentment whites had against Chinese and became violent in the 1880s. Mobs drove the Chinese out of Tacoma (November 3, 1886) and Seattle (February 7, 1886), and attempted but failed to expel them from Olympia. In 1887, whites robbed and massacred 31 Chinese miners in Hell’s Canyon, on the Oregon-Idaho border.

Despite the horrendous treatment, according to historians Ron Chew and Cassie Chinn, “They found jobs, established roots, endured discrimination and, when the laws changed, built strong family and community structures” (Chew and Chinn, p. 178).

The Naturalization Act of 1790, the first legislation limiting immigration, denied citizenship to any but free white persons. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first significant legislation limiting immigration by an ethnic group, which denied entry to Chinese under all but a few circumstances, for 10 years. If one had been a resident, a certificate had to be obtained to re-enter. The edict was extended in 1892 and in subsequent years, up to the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act of 1943.

While in China, Goon Dip married Chin Yook-Nui, who already had family members in the United States, in Seattle. Among them was Chin Gee-Hee (1844-1929), a labor contractor and businessman who became the most powerful Chinese in the Pacific Northwest in the late nineteenth century.

Returning and Getting Lucky

Still pursuing his dream, Goon Dip came back to the United States some time before 1882, but there is some discrepancy about where he debarked. In their biography of Goon Dip, the Jues, his descendants, say he arrived in Portland, where, overwhelmed by the enormity of his quest, he “sat right down on the pier and cried” (Jue & Jue, p. 42). Other “family lore” (Goon) had him landing in San Francisco, as did Seattle’s two major newspapers. In any event, luck was with him, as it would be several times in his life. The first bit of luck was his timing. Had he waited until 1882, the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act would have prevented his return.

His second bit of luck was catching the attention of Ella McBride (1862-1965), a girl his own age who, on hearing his story, convinced her parents to hire him as a houseboy, in Portland. “Sharing an adventurous spirit, the two became close friends as she assisted the young man with learning the English language and helped him adapt to the customs of his adopted country” ("McBride, Ella"). Goon Dip would name his first daughter after her. Ella went on to become internationally noted fine-art photographer, an avid mountain climber, environmentalist, and civic leader.

She must have taught him well, because he went to work for a labor contractor, Moy Bok-Hin, and, with his superior English, his savvy, and his business acumen, progressed rapidly. During his partnership with Moy, he also launched a new industry. There were many Chinese men disabled, unable to perform manual labor and to pay off contractors to whom they were indebted. Goon Dip taught them how to sew and created a garment industry in Portland.

Goon Dip’s wife later joined him, which was another bit of good fortune. Immigration laws had prohibited the settling of Chinese women and “only merchants and prominent businessmen were allowed the luxury of bringing in wives” (Jue and Jue, p. 43).

Goon Dip opened his first business, G. S. Long and Company, a dry goods store, in 1900, in Portland. It was ultimately sold to the Meier and Frank department store and Goon Dip opened another dry goods store and sewing shop in Portland, G.D. Young & Company. He also continued contracting labor for riverboat workers and cannery workers in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska.

The Goons had adopted a daughter, Martha, in China, and four children born in the United States between 1900 and 1905: Ella McBride Goon, Daniel, Rosaline, and Lillian.

Chance Favors the Prepared Mind

Goon Dip’s foresight provided another opportunity in the 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland, the first such event mounted in a West Coast city. The Chinese government had picked his old employer, Moy Bok-Hin, to serve as honorary consul for the exposition and Goon Dip and Moy bought the Oregon Hotel to help house visitors to the fair.

Goon Dip had expanded his business ventures to Seattle, where his wife’s relative, Chin Gee-Hee, had become a wealthy labor contractor and businessman. Chin returned to China in 1905 to promote and build the Sun-Ning Railway in Guangdong Province, the first railroad in South China. With his departure, Goon Dip became the most influential Chinese figure in the Pacific Northwest. He was 47 when the Chinese government appointed him honorary consul for the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, held in Seattle on the University of Washington campus. This was Washington's first world's fair. It ran from June 1 to October 16, 1909, and attracted more than 3 million fairgoers from across the state and around the world.

Anti-Chinese sentiment still ran high and the Chinese government did not sponsor an exhibit, but Goon Dip did. “Goon Dip arrived in Seattle from Portland in 1908 to organize efforts to create a Chinese pavilion for the [A-Y-P] Exposition” (Chew and Chinn, p. 184). He also “raised money on his own initiative and obtained some of the fair’s exhibits from his Chinese contacts living in Seattle, Portland, and San Francisco” ("A-Y-P -- Chinese Village"). “If he [Goon Dip] hadn’t stepped in there would be no China Day” (Ho). Other Chinese in the region contributed money for the Chinese Village, which also was promoted by Ah King (1863-1915), another successful Chinese businessman. The village, a great success, included a theater, temple, bazaar, and a restaurant and tea room owned by Ah King.

Goon Dip also profited from the fair, repeating his successful hotel venture in Portland. As buildings were being demolished during Seattle's 1909 Jackson Street regrade project, Goon Dip persuaded Chinese businessmen to move Chinatown away from the Elliott Bay tidelands, around the Columbia Railroad Depot, to the area east of the new King Street Station at 2nd Avenue and Jackson Street. The station was finished in 1906. Again anticipating huge crowds at the fair, Goon Dip built the then-elegant Milwaukee Hotel at 668 King Street. He maintained a sumptuous apartment on the top floor of the hotel, for his own use on visits to Seattle.

Canneries and Cannery Workers

During the A-Y-P Exposition, Goon Dip met E. B. Deming, head of Deming-Gould Company, who had just bought Pacific American Fisheries, Inc., of Bellingham, one of the biggest salmon canning operations in the world, with canneries on Puget Sound and in Alaska. Goon Dip became labor contractor for all Deming’s canneries and the “largest single employer of Chinese labor in the Northwest” (Jue and Jue, p. 45). The white and Chinese cannery crews were segregated.

Goon Dip remained based in Portland. He bought a new, imposing five-bedroom mansion there.

Fishing was one of most lucrative industries in the Pacific Northwest and Goon Dip made his much of his fortune as a cannery labor contractor. But while the salmon cannery business expanded, the labor pool did not, because of the immigration restrictions for Chinese. Goon Dip turned to Japanese immigrants, but restrictions would curtail that source as well. He then turned to Filipinos, many of whom had been granted citizenship for serving in the U.S. military during the Spanish-American War and World War I. As stated in the history written by his descendants, “Goon Dip was the only contractor to hire black cannery workers” (Jue and Jue, p. 47).

Alaska Gold Mining

Goon Dip went into the gold-mining business around 1918 with two Caucasian investors, Bernard Hirst and C. W. Fries, launching the Hirst Chichagof gold mine at the northern end of Chichagof Island on Alaska’s Panhandle. It was profitable until the Great Depression. Many Chinese bought shares in the mine, as they did in other Chinese enterprises. Caucasian-owned banks didn’t invest in the Chinese community and the Chinese didn’t seek their help. For the mine’s contributions to the Alaska economy, Goon Dip was honored with a mountain (Goon Dip Mountain, 1,670 feet) and a river (Goon Dip River), both on the northern end of Chichagof Island. Goon Dip also started The Marconi Company in the late 1920s, to manufacture automobile batteries, but it too became a victim of the Great Depression.

Diplomatic Duties

After his stint as honorary consul during the A-Y-P Exposition he was named permanent consul and served in that position until his death. He served under both the Manchu dynasty and the Kuomintang (National People’s Party), which took power in 1928.) His offices were in Seattle and his territorial responsibilities included Washington, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Nebraska. Historian Ho, Chui Mei reflects that “He didn’t have a lot of education, but he was very smart. What makes him different, compared with other Chinese leaders, was that he had a diplomatic position and he handled it very well over two very different regimes” (Ho interview).

His obituary in the Seattle Daily Times eulogized: “Whenever the presence of a member of the consular corps was required -- at a University ceremony, at the laying of a cornerstone, at a grand opera performance -- there would be Goon Dip” (Seattle Daily Times). Goon Dip also was honored for his philanthropy. “Goon Dip would often finance an entire college education” (Jue and Jue, p. 46). He was a member of the Seattle Chamber of Commerce and the China Club, and an owner or officer in several businesses.

Goon Dip died on September 12, 1933, at the Milwaukee Hotel. He is buried in the family plot in Lake View Cemetery, Seattle. His obituaries in Seattle’s newspapers overflowed with turgid rhetoric. The Seattle Daily Times fancied he arrived in a San Francisco Chinatown that was “strange to the pigtailed, slippered, silk-robed youngster from Canton” (The Seattle Daily Times). Mike Foster in the P-I effused: “[H]e will be mourned tonight with the wailing of flutes in the huddled streets of Old China, and with the weeping of women when the sunset flames upon the rice paddies of the South ... by grave men in the council chambers of the New World…” (Foster).

Goon Dip’s widow, Chin Yook-Nui, died on July 24, 1946. She was 81.