On November 27, 1996, William Scott Scurlock (1955-1996), dubbed "Hollywood" by the police and the "Hollywood Bandit" by the press because of his penchant for theatrical disguises, attempts to rob Seafirst Bank in Lake City of $1.08 million. It is his 15th bank robbery in the Seattle area in four and one-half years, and the Puget Sound Violent Crime Task Force has been awaiting his next attempt. Police spot Scurlock and his two accomplices in their getaway vehicle and a chase ensues. During a gun battle, Scurlock manages to escape on foot, leaving his wounded accomplices behind to be captured. He hides overnight inside a small camper in the backyard of a nearby home, but the following day is seen inside by its owners, who call the 911 Emergency Dispatch Center. While police close in on his hideout, "Hollywood" commits suicide by shooting himself in the head. The number of robberies and the amounts stolen, almost $2.3 million, make Scurlock one of the most prolific bank robbers in the history of the United States.

Son of Preacher and Teacher

William Scott Scurlock was born and raised in Virginia. His father, William Scurlock, was a Baptist minister and his mother, Mary Jane, was an elementary school teacher. Scott had three sisters, two older and one younger. Although religious, his parents were extremely permissive and Scott grew up without guidelines, never developing a moral compass. He understood the difference between right and wrong, but didn’t care. Acquaintances described Scott’s personality as charming, charismatic, and extremely manipulative. Like Peter Pan, Scott never grew up or accepted adult responsibilities, but tenaciously clung to his adolescent interests and attitudes.

In 1977, while living in Hawaii, Scurlock was fired from a landscaping company for growing marijuana on the firm's land. He moved to Olympia and in 1978 enrolled at Evergreen State College, where he studied organic chemistry and biochemistry. And that’s where he learned how to make “crystal meth,” a refined, crystalline form of methamphetamine. Scurlock used Evergreen’s chemistry laboratory to manufacture the highly addictive, illegal drug, using ephedrine, an ingredient found in non-prescription cold and allergy medicine, and chemicals stolen from the school. He “attended classes” at the college sporadically for six years, while becoming a major source of supply of the drug in the Northwest.

Scurlock rented a nondescript, 1,700-square-foot farmhouse which sat on a 19.25-acre tract of land at 1506 Overhulse Road NW in Olympia, near Evergreen State College. There was a large barn on the property, which was the perfect place for hiding a clandestine laboratory. In the early 1980s, he started building a treehouse in a stand of seven cedar trees on the back portion of the acreage, using materials he stole from nearby lumberyards. It took Scurlock and his friends many months to construct the 1,500-square-foot, unstructured treehouse. It was three stories high and reached more than 60 feet above the ground, facing Mount Rainier. The house had 30 windows, electricity, plumbing, a full kitchen, a working bathroom and a fireplace. When the farm was put up for sale in 1990, Scurlock used $110,000 from his cache of drug profits to purchase the property and protect his unauthorized, rickety creation.

From Drugs to Banks

In 1990, Scurlock’s main meth distributor was murdered, making him realize just how violent and dangerous the drug business was. He stopped manufacturing crystal meth, but now needed another source of easy money to support his extravagant lifestyle. Because Scurlock liked to travel extensively, he never held a real job his entire life. The caches of drugs and money, sealed in plastic buckets and buried on his property, financed his activities for approximately one year. Now, running low on funds, Scurlock decided that robbing banks would be a good choice and a great adventure. He chose a target and then recruited a close friend from college, Mark John Biggins (b. 1954), to be his backup inside the bank. Biggins's girlfriend, Traci Marsh, was persuaded to drive the getaway car.

Scurlock and his friends pulled their first bank robbery shortly before noon on Thursday, June 25, 1992. It was the Seafirst Bank (now Bank of America) at 4112 E Madison Street in Seattle’s exclusive Madison Park neighborhood. Scurlock disguised himself with a false nose and heavy theater makeup and Biggins wore a plastic Ronald Reagan mask. The robbery was successful, no one got hurt, and the trio returned to Olympia with $19,971. Biggins decided he didn’t like robbing banks and moved to Darby, Montana, with his girlfriend, where he got a job building log cabins. Biggins's hiatus from robbing banks would last for four years.

Scurlock enjoyed the thrill he experienced from the heist and decided to make robbing banks his new profession. On Friday, August 14, 1992, he brazenly entered the same Seafirst Bank in Madison Park, alone and brandishing a handgun, and stole $8,124. Although Scurlock was heavily disguised, his demeanor and intimidating style were much the same as his first robbery. This violent method is known as a “takeover” or “take-charge” robbery and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and Seattle Police Department initially nicknamed him the “Take Charge Robber.”

Over the next three months, Scurlock and his accomplices robbed four more banks in Seattle, then stopped. The last heist was on Thursday, November 19, 1992, at the Hawthorn Hills branch of the Seafirst Bank, 4020 NE 55th Street, which netted the gang $252,000. By now, the police and FBI were quite familiar with Scurlock’s theatrical disguises and style, gleaned from witnesses and bank surveillance cameras, and changed his sobriquet to “Hollywood.” The media preferred “Hollywood Bandit.”

Bandit Resumes Robbing Banks

Scurlock spent the $322,870 he had stolen in 1992 within a year and then decided to resume his favorite occupation, robbing banks. He had enlisted a childhood friend, Steven Paul Meyers (b. 1950) to help him launder the money through numerous trips to gambling casinos in Las Vegas, Nevada. Now he wanted Meyers to help him rob banks. He chose the same Seafirst Bank in Hawthorn Hills where he had made a quarter-of-a-million-dollar score the previous year. Scurlock and Meyers watched the bank for several days, then on Wednesday, November 24, 1993, the day before Thanksgiving, made their move. Scurlock went inside the bank while Meyers stayed outside in his vehicle with a portable two-way radio, monitoring police frequencies on a scanner. The robbery took place without a hitch, but this time they only got $98,571. Scurlock buried all the loot on his property, except for $5,000 which he magnanimously gave to Meyers for his participation. It was the amount Scurlock typically paid accomplices, since he was the mastermind and took the most risks, and since it kept them hungry for more.

Scurlock and Meyers robbed five banks in 1994, three in Seattle and two in Portland, stealing a total of $263,599. In January 1995 the bandits hit two banks. Scurlock stole $11,924 on January 18 from the Wallingford branch of the First Interstate Bank (now Wells Fargo Bank), 1701 N. 45th Street, but a dye pack exploded, coloring the money red, and he had to abandon the loot. Undeterred, on January 27 Scurlock returned to the Madison Park Branch of the Seafirst Bank for the third time. He carried away $252,466, enough to tide him over for the rest of the year.

Closing in on Scurlock

Meanwhile, the Puget Sound Violent Crimes Task Force, a group composed of FBI agents, Seattle Police detectives, King County Sheriff’s detectives, and other law enforcement agencies, made catching the bandit, now dubbed “Hollywood,” their top priority. Aside from the money, the police were worried it was only a matter of time before someone was killed. They carefully charted the details of the robberies and poured over scores of surveillance photographs, establishing his modus operandi. The pattern seemed to be connected to the amounts of money the bandit stole. They calculated that Hollywood was spending about $20,000 a month and determined approximately when he would need more cash. During this period, the task force would be waiting near Hollywood’s favorite banks, Seafirst and First Interstate, in neighborhoods where he had made big scores in the past. In addition, the Washington State Bankers Association, working in conjunction with Crime Stoppers of Puget Sound, offered a $50,000 reward for information leading to the bandit’s arrest and conviction.

For the next bank heist, Scurlock enlisted the help of both Steve Meyers, who would continue as the outside lookout, and Mark Biggins, who would assist inside the bank with crowd control. On January 25, 1996, the gang robbed the Wedgwood branch of First Interstate, 8517 35th Avenue NE and escaped with $141,405. Coveting a much larger stash of money, Scurlock hit the Madison Park branch of the First Interstate Bank, 4009 E Madison Street on May 22, 1996 for $114,978. But it wasn’t enough to satisfy his lust for money and adventure, so “Hollywood” decided to rob three banks in one day. Potentially, it would be his last big score and something the police and FBI would never expect. He targeted Seafirst Bank branches in Lake City, Green Lake, and the University district. But Scurlock changed his mind at the last minute, deciding to rob only the branch in Lake City.

Scurlock's Last Heist

At 5:41 p.m., Wednesday, November 27, 1996, Scurlock and Biggins entered the Seafirst Bank at 2800 NE 125 Street, while Meyers lingered nearby in a getaway vehicle. The minute they walked through the door, one of the tellers, having been briefed about the heavily disguised robber, hit the silent-alarm button. The robbers forced everyone to lie down on the floor, and while Biggens held them at gun point, Scurlock entered the vault with the head teller and stuffed bricks of money into a large nylon duffel bag. The bandits were out of the bank in four minutes and calmly walked down the street. A customer disobeyed orders, however, following them to a blue Dodge Caravan and then calling the 911 Emergency Dispatch Center with a description of the car and their direction of travel.

Although the task force had dozens of police officers on alert for a robbery, Lake City was a first, and all the cars were patrolling in the wrong neighborhoods. Due to a severe wind and rain storm and holiday traffic, the bank robbers were slow to leave the area. Even though they switched from the getaway car to a white Chevrolet Astrovan, it wasn’t long before three task-force members, acting primarily on instinct, began tailing the van, intending to make a traffic stop. While Scurlock calmly drove south, Meyers and Biggins began rummaging through the bundles of bills on the floor of the van, looking for electronic tracking devices.

Scurlock didn’t wait to be pulled over, however, and stopped the van on 24th Avenue NE in the Ravenna neighborhood. He jumped out with a 12-gauge shotgun and pointed it at the task force officers, but he was unable to fire the weapon. The officers fired several shots at the van, which immediately sped away. After a few more blocks, the van stopped and Meyers exited the side door with a shotgun and opened fire. The officers returned fire and once again the van sped away. Two blocks later, someone inside the van broke out the right rear window and began firing an assault rifle. Scurlock shut off the headlights, bailed out of the vehicle while it was slowly moving and fled on foot. The van continued through a front yard at NE 77th Street and 20th Avenue NE and struck a house.

Inside the van, the officers found Biggins and Meyers, who had both been seriously wounded; two 12-gauge shotguns; a U.S. military .308 caliber M-14 semiautomatic rifle; two 9mm semiautomatic pistols; three Motorola two-way radios; a police frequency scanner; and $1.08 million in cash. Seattle Fire Department’s Medic One paramedics transported both suspects to the emergency room at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle for treatment of non-life-threatening gunshot wounds. During questioning, Meyers told FBI Agent Shawn Johnson that Scott Scurlock was the mastermind behind the heist and that he lived in Olympia.

Searching for the Fugitive

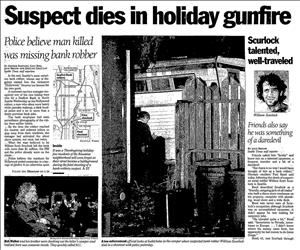

Meanwhile, the Seattle Police Department established a six-block perimeter around the area where Hollywood escaped and was thought to be hiding. While police officers went door-to-door trying to determine if anyone was being held hostage or had seen anything unusual, Emergency Response Teams (ERT) and K-9 units began methodically searching for the fugitive, who was known to be armed with a 9-mm semiautomatic Glock pistol. Although it was pouring rain and extremely windy, the hunt for Hollywood continued throughout the night, but without success.

At 2:00 p.m. on Thanksgiving Day, November 28, 1996, Robert and Ronald Walker were visiting their 85-year-old mother, Wilma C. Walker, for dinner. Her house, located at 7518 20th Avenue NE, was approximately two blocks from where Meyers and Biggins had been captured. Ronald had a 10-foot camper stored on sawhorses in Wilma’s back yard, about 40 feet from the house. The two brothers heard about the hunt for the fugitive and the $50,000 reward and decided to scout around their mother’s property. Seattle Police officers had visited Wilma Walker and searched her back yard, but she was concerned and asked the boys to check the camper, which hadn’t been searched. The camper door was still secured on the outside with a cable and padlock, but there was a small covered hatch at the front of the camper through which a lean person could gain access.

The Walker brothers became suspicious when they noticed the camper door had been locked from the inside and the curtains drawn. Robert attempted push open the hatch door but it wouldn’t budge. Meanwhile, Ronald fetched a stepladder, peered through the small window in the cab-over sleeping compartment, and saw someone inside. The brothers quietly withdrew and while Robert watched the camper, Ronald called the 911 Emergency Dispatch Center. Within minutes, several Seattle police cars arrived and officers surrounded the camper.

Showdown

As patrol officers took up defensive positions, Sergeant Howard Monta tried to elicit a response from the person inside, but was unsuccessful. Finally, he pried a louvered window open and emptied two canisters of capsicum pepper spray into the interior, without result. When Sergeant Monta attempted to unlock the door, there was a single gunshot and he scrambled for cover. The patrol officers responded by firing over 30 rounds at the camper shell.

Dozens of Seattle police officers, FBI agents and detectives from the Puget Sound Violent Crime Task Force arrived at the scene, cordoned off a five-block area, and began evacuating nearby homes. The Seattle Police brought in an armored vehicle and positioned it near the camper in preparation for an assault. Hostage negotiators attempted repeatedly to contact the person inside, using a bullhorn, but were unsuccessful. At 6:00 p.m., ERT fired a tear-gas shell into camper, but still there was no response. They waited 20 minutes, and then fired another shell into the camper. At 7:40 p.m., ERT officers in gas masks carefully approached the camper, and Sergeant Paul McDonagh opened the door. They found a man lying dead on the floor in the dinette with a 9-mm Glock pistol and one empty shell casing next to his body.

Aftermath

Based on information from Steve Meyers, the FBI served a federal search warrant on Scurlock’s houses and property in Olympia on Thanksgiving Day. They discovered a cache of weapons, which included handguns, a silencer, several rifles, two sawed-off shotguns, and a large store of ammunition. The agents also seized over $20,000 in cash, passports, airline tickets, police frequency scanners, and portable two-way radios. Hidden under the floor in the barn, they found a secret room where Scurlock applied his makeup, stored his disguises, and counted the loot.

After the Seattle Police Homicide Unit completed their crime scene investigation, the body was transported to the Harborview Medical Center morgue for autopsy. On Friday, November 29, the King County Medical Examiner’s Office officially identified the man as William Scott Scurlock and Dr. Norman Thiersch, the pathologist, ruled his death a suicide. Hollywood died from a single, self-inflicted gunshot to the head. Although there were six other bullet wounds to Scurlock’s body, Dr. Thiersch concluded they were most likely inflicted postmortem and did not to contribute to his death.

On Monday morning, December 2, 1996, Steve Meyers, age 46, and Mark Biggins, age 42, were charged in absentia in Seattle District Court with suspicion of armed robbery and attempted murder of police officers, both state offenses. Judge Darcy C. Goodman set bail at $1 million each. That afternoon, the defendants were also charged in federal court with bank robbery and use of a firearm in commission of a crime. U.S. Magistrate John L. Weinberg scheduled a detention and preliminary hearing for Monday, December 10, 1996 and also set bail at $1 million each. In the preliminary hearing, Magistrate Weinberg ruled there was ample evidence to hold Meyers and Biggins for trial and ordered them held without bail.

Putting Their Lives at Stake

Meanwhile, when the Walker family attempted to collect the $50,000 reward offered by Seafirst and Wells Fargo Banks for the “arrest or conviction” of the bank robbers, they were met with resistance. The banks said that technically the Walkers didn’t qualify for the reward but offered them $10,000 in appreciation for their troubles. However, after a deluge of negative publicity from the media, coupled with thousands of telephone calls from angry citizens, the banks relented and agreed to pay the full $50,000.

In a brief ceremony on Wednesday, December 4, 1996, Seafirst Bank Chairman John Rindlaub presented the Walkers with a check for $50,000. And later in the day, Stanley Naughton, president and chief executive officer of Seattle-based Pemco Financial Center donated another $10,000, remarking he was disappointed that members of the financial community would attempt to renege on their offer of a reward when citizens put their lives at stake.

Meyers and Biggins Face the Law

On Thursday, February 27, 1997, Meyers and Biggens pleaded guilty in federal court before U.S. Magistrate Philip K. Sweigert to one count of conspiracy, one count of armed bank robbery, two counts of assault on a federal officer, and one count of use of a firearm in commission of a felony. On Thursday, May 15, 1997, U.S. District Court Judge William L. Dwyer (1929-2002) sentenced both defendants to 21 years and three months in prison, at the low end of the federal sentencing guidelines, plus an additional five years of supervised release. The sentences included an automatic 10 years for using assault weapons when firing upon federal officers. Because their crimes were so egregious and the defendants had confessed to prior bank robberies, Assistant U.S. Attorney William H. Redkey had asked for 24-year sentences. The state charges were dismissed without prejudice.

Steven Paul Meyers was an inmate at the Forest City Federal Correctional Institution in Forest City, Arkansas, and was released from custody on December 6, 2013. Mark John Biggins was an inmate at the Englewood Federal Correctional Institution in Littleton, Colorado, and was releases from custody on June 3, 2015.

The number of robberies and the amounts stolen, almost $2.3 million, make William Scott Scurlock one of the most prolific bank robbers in the history of the United States.

Banks robbed by the “Hollywood Bandit”

-

June 25, 1992, Seafirst, 4112 E Madison Street -- $19,971

-

August 14, 1992, Seafirst, 4112 E Madison Street -- $8,124.50

-

September 3, 1992, U.S. Bank, 4200 SW Edmonds Street -- $9,613

-

September 11, 1992, University Savings and Loan, 4568 Sand Point Way NE -- $5,739

-

October 5, 1992, Great Western Bank, 2610 California Avenue SW -- $27,423

-

November 19, 1992, Seafirst, 4020 NE 55th Street -- $252,000

-

November 24, 1993, Seafirst, 4020 NE 55th Street -- $98,571

-

January 21, 1994, U.S. Bank, 8702 35th Avenue NE - $15,803

-

February 17, 1994, Seafirst, 4020 NE 55th Street -- $114,000

-

June 24, 1994, First Interstate, 3782 SE Hawthorn Boulevard, Portland, Oregon -- $00 (aborted)

-

July 13, 1994, First Interstate, 1630 Queen Anne Avenue N -- $111,796

-

December 20, 1994, U.S. Bank, 4727 SE Woodstock Boulevard, Portland, Oregon -- $22,000

-

January 18, 1995, First Interstate, 1701 N 45th Street -- $11,924 (dye pack exploded, money abandoned)

-

January 27, 1995, Seafirst, 4112 E Madison Street -- $252,466

-

January 25, 1996, First Interstate, 8517 35th Avenue NE -- $141,405

-

May 22, 1996, First Interstate, 4009 E Madison Street $114,978

-

November 27, 1996, Seafirst, 2800 NE 125th Street -- $1,080,000