On March 22, 1943, ground is broken at Richland, Benton County, for the Hanford Engineer Works Village, a federally sponsored planned community to house workers and their families at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. The site is chosen because it is sufficiently remote from population centers to preserve the secrecy of this part of the highly secret Manhattan Project, yet close enough to Hanford (15-30 miles to various parts of the reservation) to allow workers in Richland an easy bus commute. The Manhattan Engineering District (MED) of the Army Corps of Engineers selects the DuPont Company to construct both its industrial facilities at Hanford and the housing village at Richland. A successful and prolific Spokane architect, Swedish-born Gustav Albin Pehrson (d. 1968), is chosen to plan and complete the Richland village, which will eventually house nearly 16,000 residents. Pehrson initially designs nine different house types of various sizes and configurations to which he assigns letters of the alphabet. Some later residents will live in prefabricated houses not of Pehrson's design. Eventually there will be 2,500 permanent housing units, many still in use today.

War, Sacrifice, and a Town Remade

For the Hanford project, the federal government condemned 428,000 acres in the Columbia Basin. The tiny town of Richland, with its surrounding orchards and asparagus farms, was part of this acquisition. Approximately 250 residents were forced to give up homes, farms, and businesses. They complained about low valuations and inadequate compensation, but many realized they were making a contribution to the war effort. Because so many of the existing buildings were of poor quality (some even lacked indoor plumbing), only 26 could be salvaged for future use. Architect Pehrson objected even to these, stating “the current buildings are conspicuous and so prevent the effect from being as harmonious as the planners had hoped” (Harvey, 10).

Pehrson and his hastily enlarged staff were required to produce plans for the entire village in less than three months. Construction began in late April, 1943, and the first homes were ready for occupancy by July. But the initial phase of the project was not finished until June 1945, almost two years later.

The difference in goals between the MED and DuPont immediately became apparent. Whereas the MED wanted only the most basic accommodations, DuPont expected higher quality housing for its employees. Although Pehrson was willing to compromise by eliminating garages, fireplaces, and most porches from the plans, he and DuPont held fast for using quality construction materials, providing spacious yards with pleasant views, retaining shade trees and old orchards, and establishing green belts. DuPont also wanted plenty of commercial buildings in an attractive shopping area. The MED preferred a minimum of such construction.

Despite the relentless MED priorities of speed and economy, Pehrson and the Dupont Company succeed in providing suitable and comfortable homes for Hanford workers in the now-federally owned company town. In addition to housing, Pehrson’s comprehensive design included sidewalks, utilities, municipal buildings, medical facilities, schools, and businesses. Streets were laid out with curved, rather than right-angled, intersections. Plans had to change in various ways as the needs of the community evolved and population grew. Additional styles of homes were added until 1951, each bearing a later letter of the alphabet.

Building Community

Pehrson was sensitive to the subtle beauty of the “hills and plateaus ... full of nuance” and “the skyscapes and sunsets [that] rival the finest in the nation” (Kubik, 38). He tried to plan a community that took full advantage of these scenic values and the natural contours of the gently rolling terrain. He was also aware that these houses needed cross-ventilation in the hot Columbia Basin climate, and he placed windows accordingly. Pehrson’s November 1943 report to DuPont noted that the plan included “tree-lined parkways dividing the town naturally into neighborhoods, providing pleasant and safe walks for students going to and from school” (Harvey, 8).

Much of the timber used for framing was high-quality Douglas fir, salvaged from the Tillamook Burn, a 1929 fire near the northern Oregon coast, and exteriors were clad in wood shingles. The duplexes and prefabs had Doug fir or hardwood floors, while the single-family homes had hardwood. All houses had generous closet and storage space, linoleum in kitchens and bathrooms, and quality fixtures. DuPont provided furniture and appliances, and the nominal rent included electricity, water, and coal. The initial houses ranged in size from the meager 880-square-foot, two-bedroom, one-bath duplex "B" house to the two-story, 1,536-square-foot "L" house with four bedrooms and two baths. Most of the designs included basements with laundry facilities and coal furnaces, usually later retrofitted to burn oil. Unfortunately, insulation was minimal.

In place of garages, each block had at least one compound where residents could park their cars; some of the later prefabricated houses had carports. Pehrson planned the neighborhoods along egalitarian principles, with a mixture of sizes and types of housing “to achieve as even an admixture as possible of all types, and avoid the appearance of ‘better’ or ‘poorer’ districts” (Kubik, 35). But somehow, the executive-level houses often ended up on the more desirable lots closer to the Columbia River.

In addition to houses, Pehrson designed dormitories for single men and women, a hotel (originally called the Transient Quarters or Clubhouse, later the Desert Inn) and a hospital. Pehrson retained a school just completed by the original townsfolk of Richland, but built two new grade schools and a high school. For churches, the MED provided two standard army chapels, one for Protestants and one for Catholics. Each held its first service on Christmas Eve, 1944. As the population grew, Sunday school and other church activities spilled over into public schools and the grange hall. Before many years had passed, individual denominations began building their own churches.

Not for Everybody

Despite decent housing and well-paying jobs, many residents of Richland did not stay, driven out largely by the frequent dust storms, dubbed “termination winds” because they led to many requests for termination pay and release from employment at Hanford. Residents at the time were unaware that those winds carried serious health hazards, the result of Hanford’s plutonium production. Yet many did like the town and their work and stayed on into the postwar era as Hanford changed from a wartime to a Cold War civilian operation, and new residents joined them.

James Morris (b. 1940), who lived in Richland as a child from 1949 through 1951, recalls a good small-town atmosphere. His father was pastor of the newly organized Presbyterian church, and the family of five lived in a rancher (possibly a prefab) on the west side of town. Jim enjoyed Sacajawea Elementary School, recalling that because almost everyone was from somewhere else, no one was treated like an outsider. There was a huge sand dune behind his house, great for climbing up and rolling down or playing “King of the Hill.” Less fun was raking the sand out of the grass after a windstorm. Jim’s mother hated the sand, which even got into the hems of skirts, and would spoil a newly hung laundry when the wind came up. He also remembers picking wild asparagus that grew along the road, possibly a remnant of a former farm.

A Company Town No More

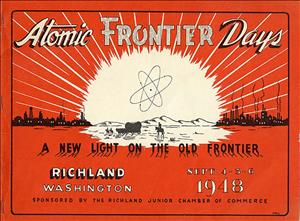

In 1946 General Electric replaced DuPont as the major contractor at Hanford, and in 1947, the civilian Atomic Energy Commission replaced the Manhattan Engineering District. The Hanford Engineer Works was renamed Hanford Works, or simply Hanford. The Cold War saw an expansion and upgrade of this nuclear facility and a corresponding growth in Richland. Soon there were 450 new prefabs and 1,000 more ranch-style homes to accommodate the growing work force. For the past 20 years, the ongoing cleanup of hazardous waste at Hanford has employed many residents of the Tri-Cities of Richland, Pasco, and Kennewick.

The postwar era brought about the gradual withdrawal of the federal government and its contractors as landlords at Richland, and occupants were allowed to buy their homes. The city evolved from a company town to an independent city incorporated as a first-class city on December 10, 1958. Of the many Pehrson houses still standing, some have been altered considerably, yet many are recognizable as the original letter houses.