On August 23, 1901, Charles W. Nordstrom (1849-1901) is hanged in the garret of the King County Courthouse for the premeditated murder of 20-year-old William Mason. This notorious murder, which took place at the Mason hop farm near Cedar Mountain (King County) on November 27, 1891, received national media attention because Nordstrom's attorney, James Hamilton Lewis (1863-1939), had been able to forestall the execution for almost 10 years through repeated appeals to the Washington Supreme Court and the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Masons and Their Hop Farm

Thomas Mason, an Irish immigrant, owned a hop farm near Cedar Mountain, a small mining town on the Cedar River, approximately seven miles east of Renton in King County. He moved his family from Michigan to Washington state in the early 1870s and made his living mining coal and cultivating hops (a bitter herb used to flavor beer). In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, hop cultivation was a lucrative business and the crop thrived in the fertile valleys of King and Pierce counties.

According to the 1887 Washington Territorial Census, the Mason family consisted of nine members: Thomas, head of household, age 46, Jane, housewife, age 40, John, age 20, William, age 15, Frank, age 13, Joseph, age 11, Alice, age 9, Annie, age 7, and Thomas Jr., age 5. The 1889 Washington Territorial Census revealed that Jane had died, but the family was still farming at Cedar Mountain. In the fall of 1891, Thomas Mason and three sons, William, Joseph, and Thomas Jr., were living on the farm, and daughters Alice and Annie were attending school in Seattle at Holy Names Academy. For more than a year, William had been employed in Seattle as an apprentice blacksmith, but met with an unfortunate accident. While shaping a piece of hot steel on an anvil, he was blinded in one eye by a metal fragment and had returned home to convalesce.

William Mason's Death

At approximately 6:30 p.m. on Friday, November 27, 1891, William Mason, his brothers, Joseph and Thomas Jr., cousin Charles Gallagher, and Robert Eckman, a hired hand, were seated at a table in the Mason farmhouse, eating dinner, when an unseen assassin fired a bullet through the window. Startled by the gunshot, everyone jumped from their chairs except William who grasped his left side with both hands and fell over, striking his head against the wall. With Joseph’s help, Gallagher carried William into a bedroom and placed him on a bed. He died a minute later, without regaining consciousness.

It was dark and misty outside the farmhouse, precluding those inside from seeing who had ambushed William or in which direction he fled. Gallagher and Joseph Mason notified a neighboring farmer about the shooting, then went down to the Columbia and Puget Sound Railroad station at Cedar Mountain and telegraphed King County Sheriff James H. Woolery (1851-1925) in Seattle with the message: “Will Mason was shot and killed by an unknown party tonight. Please find his father, Thomas Mason, at Frank Doran’s rooming house, corner of Fifth Avenue and Jefferson Street, and tell him the news. Come at once” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer).

Gallagher also sent a brief message to Thomas Mason, who was in Seattle to sell his season’s crop of hops. “Willie was shot this evening. Come at once and bring sheriff” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer). But Mason had completed his business in the city and left the rooming house at about 4:00 p.m., intending to catch the evening train for Cedar Mountain. At the last minute, however, he changed his mind and checked into a hotel. Mason didn’t learn of William’s murder until he read about it in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer on Saturday morning.

Tracking Down the Killer

Sheriff Woolery and Deputy John F. “Jack” McDonald caught the first train from Seattle to Cedar Mountain and then proceeded to the Mason farm on horseback. After speaking with the Masons and several neighbors, who had gathered at the farm, Woolery determined the most likely suspect was Charles W. Nordstrom, also known as Swanson, a 42-year-old Swedish immigrant who lived nearby in an abandoned shack, and had had a recent dispute with the Masons over $3.85 in unpaid wages. Several weeks earlier, he had contracted with the Masons to grub several acres of farmland and dig a ditch, but left the job unfinished. Although paid for his work, Nordstrom believed he was owed more money and left the farm uttering threats and cursing in Swedish. A heavy drinker, Nordstrom had a belligerent nature, had no friends, and was often in fights. He was known for his violent temper and for nurturing grudges. To make matters worse, he was usually armed with a handgun or rifle.

After examining the crime scene, Woolery determined the assassin had fired from a position behind a split-rail fence, approximately eight feet from the north side of the farmhouse. He found an empty shell casing, which identified the probable murder weapon as a powerful .45-70 caliber Winchester Model 1886 lever-action rifle. The carcass of the Masons’ missing bulldog was discovered later by Deputy McDonald, bludgeoned to death and hidden in the bushes. The dog hadn’t raised a ruckus, suggesting it was familiar with the intruder and hadn't felt threatened.

Tracks in the soft dirt showed the killer was wearing rubber work boots, with a particular arrangement of three nails in the heel, and led off in a northwesterly direction. A six-man posse followed the footprints for over a mile and a half before loosing the trail in dense underbrush. They found the tracks again on an old trail leading toward a cabin owned by Thomas Lindsey, a coal miner who worked and lived in Gilman. At the bottom of a path leading to the cabin, the gunman had removed the rubber boots, walked up the muddy lane in his socks and entered the shack. Inside, they found the rubber boots and Nordstrom’s old black slouch hat, with a page from a memorandum book inside with notes written in Swedish. Different tracks, made by a pair of leather boots, with an identifiable repair patch on the right sole, were observed leading away from the cabin and heading up a seldom used mountain trail in the direction of Gilman.

Meanwhile, Sheriff Woolery went back to Cedar Mountain and wired his deputies at Tolt (now Carnation) and Gilman (now Issaquah) to station men at every trail and road intersection, and be on the lookout for Nordstrom. He sent Deputy Jack McDonald up the Snoqualmie wagon road toward Tolt while he proceeded to Gilman to investigate rumors that Nordstrom was working at the Seattle Coal and Iron Company mine. At the mine office, he learned that Nordstrom started working in the coal bunkers on Thursday, November 12, but quit after work on Wednesday, November 25, and had not returned. Nordstrom told witnesses “he was going after money and a settlement and if he did not get it, there would be trouble” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer). Believing he would return to Gilman, Sheriff Woolery dispatched posses to hunt for Nordstrom and posted a lookout at the Dexter Horton & Company bank where the suspect had an account. At about 4:00 p.m., Woolery started back to Cedar Mountain to attend the coroner’s inquest scheduled for Saturday evening at the Mason farm.

Coroner's Inquest

King County Coroner Dr. George M. Horton, Deputy Coroner James A. Green, and King County Deputy Prosecutor William Caldwell arrived at Cedar Mountain on the evening train from Seattle. Charles Gallagher met them at the station with a horse-drawn lumber wagon and, with the help of a neighbor on horseback with a lantern, took them on a torturous two-hour ride up the mountainside to the Mason farm.

The postmortem examination by the coroners disclosed that William Mason had been killed by a .45 caliber bullet which entered his left arm approximately three inches below the shoulder, breaking the humerus. The slug passed latterly through his body, piercing his heart and both lungs, entered his right arm, struck the humerus and lodged under the skin. He bled to death in less than one minute.

Dr. Horton then selected six jurors from among the friends and neighbors who had gathered there for the inquest. Prosecutor Caldwell questioned several witnesses, including those who had been present at the murder, who all fingered Charles Nordstrom as the likely culprit. After deliberating for 30 minutes, the coroner’s jury declared William Mason had met his death after being shot by Nordstrom.

Nordstrom's Arrest

On Sunday afternoon, November 29, 1891, Sheriff Woolery received a telegram at his residence in Seattle from Deputy McDonald. “I got Nordstrom, alias Swanson, at three o’clock this afternoon between Gilman and Fall City” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer). Deputy McDonald had tracked the suspect’s boot prints from the Lindsey cabin to a shack near Gilman. While scouting the road to Fall City, he saw a man carrying a Winchester rifle and asked if his name was Nordstrom. When the man replied “yes,” McDonald snatched away his rifle and placed him under arrest. At the Gilman jail, McDonald seized Nordstrom’s leather boots and muddy socks, the Winchester Model 1886 rifle, eight .45-70 cartridges, a black cap, and a memorandum book as evidence.

Nordstrom told Deputy Benjamin Stretch he had no idea why he had been arrested. He said the Masons owed him money, but knew nothing about William being killed. Nordstrom had purchased the Winchester rifle and a box of Winchester .45-70 caliber cartridges on Thursday, November 26, at Hardy & Hall Arms Company in the Pioneer Building on Front Street (now 1st Avenue) in Seattle to take on a trip through the Cascade Mountains to Eastern Washington.

Sheriff Woolery transported Nordstrom to Seattle under heavy guard on the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railway. He was lodged in the county jail, located in the basement of the new King County Courthouse (built in 1890), on First Hill at 7th Avenue and Alder Street (now Harborview Overlook Park). On Monday, December 7, 1891, Nordstrom was charged by Information with first-degree murder and entered a plea of not guilty at his arraignment before King County Justice of the Peace Edward Von Tobel. The preliminary hearing was held in chambers to avoid any demonstrations. A trial date was set for January 8, 1892, and the Justice appointed Seattle attorneys Nils Soderberg and Edward B. Palmer to defend Nordstrom. Following the hearing, Nordstrom was remanded to the custody of the King County Sheriff and held without bail.

The Trial

Trial began in the courtroom of King County Superior Court Judge Thomas J. Humes (1849-1904) at 9:00 a.m. Friday, January 8, before a packed house. After impaneling the jury, King County Prosecutor John F. Miller and his assistant Austin G. McBride outlined the state’s case against the defendant for first-degree murder. Nordstrom believed the Masons owed him money for work he performed on their farm, which was left uncompleted. He was so resentful, he purchased a hunting rifle in Seattle, approached the farmhouse in the dark, and shot through the kitchen window, killing William Mason. The prosecution intended to prove through testimony and a multitude of exhibits, including the murder weapon, a pair of muddy socks, and two pairs of boots, that Nordstrom had the means, motive, and opportunity to commit the murder. He was followed by expert trackers and arrested while attempting to abscond into Canada.

The trial continued well into the night and resumed early Saturday morning. The prosecution rested its case on Saturday afternoon, January 9, after calling 22 witnesses to testify. Defense Attorney Soderberg then moved for dismissal on the grounds the prosecution case against Nordstrom was wholly circumstantial, rife with hearsay testimony, and failed to prove he was the killer. After Judge Humes denied the motion, Soderberg made his opening statement for the defense.

Soderberg stated Nordstrom held no grudge against the Mason family, so an unknown enemy of William Mason committed the deed. The defendant had purchased the .45-70 caliber Winchester rifle and a box of Winchester cartridges in Seattle, intending to take it on a trip into the Cascade Mountains. That night he got drunk in Seattle and lost the box of ammunition. On the day of the murder, Nordstrom traveled to Renton where he bought another box of .45-70 caliber cartridges and a bottle of whiskey, and then visited various saloons before starting out for Gilman to collect some money. He apparently spent the day wandering around central King County in a drunken stupor, pausing occasionally to nap in the underbrush alongside the trail. Nordstrom eventually wandered into Gilman at about 8:00 p.m. and spent the rest of the night drinking in saloons. Finally, the rubber work boots, which the defense conceded the killer wore, were too small for his feet and the leather-boot prints the posse followed were old ones.

The defense called only two witness: Thomas Rowley, a Gilman saloonkeeper, and Nordstrom himself. Rowley testified that although he didn’t actually see Nordstrom, a patron said he was in town with a gun and wanted Deputy Ben Stretch to arrest him. At the objection of the prosecution, Judge Humes had the hearsay testimony stricken from the record.

Nordstrom took the stand at 4:30 p.m. and the first thing Defense Attorney Soderberg did was give him the rubber work boots to pull on. Nordstrom happily obliged, but indicated his feet were too large and couldn’t get them on. Then he hopped around in front of the jury box and let members of the jury attempt to force the boots onto his feet. Next, Nordstrom donned the muddy socks he wore when arrested and again tried to pull on the boots, but without success. This flamboyant display was intended to impeach not only a key piece of evidence but also the prosecution’s entire circumstantial case.

At 11:00 p.m., Soderberg finally completed his direct examination of Nordstrom, whose testimony was vague and often contradictory. Judge Humes adjourned the court until 9:00 a.m. on Monday, January 11, 1892, and had the bailiff sequester the jury.

When court was reconvened on Monday morning, Assistant Prosecutor McBride began Nordstrom’s cross examination, which lasted for several hours. His testimony was often inconsistent with prior statements and when asked for clarification, he usually replied he had been too drunk to remember. During rebuttal, McBride introduced witnesses to counter the attempt by the defense to impeach the prosecution’s exhibits. A shoemaker from Seattle measured Nordstrom’s feet and testified the rubber boots were large enough to fit the defendant. He also measured Sheriff Woolery’s and Charles Gallagher’s feet and testified that both were larger than Nordstrom’s. Then, both Sheriff Woolery and Gallagher were called to the stand and pulled on the rubber boots. Other witnesses were called to dispute Nordstrom’s claim that he was in Gilman on the night of the murder, some 10 miles away from the Mason farm.

The case was concluded at 4:00 p.m. Tuesday, January 12, 1892 and went to the jury. At 5:00 p.m. on Wednesday, after deliberating for more than 24 hours, the jury found Nordstrom guilty of first-degree murder, which carried a mandatory sentence of death. Defense Attorney Soderberg immediately filed a motion with the court for a new trial and an arrested judgment, both of which were denied. Then Soderberg filed a notice of appeal to the Washington State Supreme Court on behalf of the defendant based on insufficient evidence, jury prejudice, and judicial error. Nordstrom was returned to the King County jail to await sentencing and an execution date.

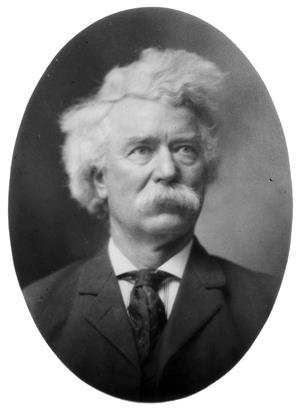

James Hamilton Lewis and His Defense

With the trial over, Judge Humes relieved attorneys Soderberg and Palmer from any further legal responsibilities on Nordstrom’s behalf. The case was adopted by James Hamilton Lewis, who was tireless in his efforts to obtain a new trial for Nordstrom, or at least have his sentence commuted to life in prison. (Lewis represented Washington in the U.S. Congress for two years -- 1897-1899 -- during the appeal and later represented Illinois in the U.S. Senate for many years). Over the next nine years, Lewis argued the case before the Washington State Supreme Court, the U.S. District Court, and the U.S. Supreme Court numerous times without result. The courts all affirmed the judgments made by the lower court and the verdict imposed by jury.

The jailers considered Nordstrom, who was generally quiet and good-natured, to be a model prisoner. He had resided at the King County jail for so long the other prisoners regarded him as its patriarch. But Nordstrom absolutely refused to discuss any subject related to murder or death. On Sunday night, March 17, 1895, Nordstrom had a chance to escape. Thomas Blanck, a psychopathic killer, had been convicted in King County Superior Court of first-degree murder in 1894, and sentenced to hang. Like Nordstrom’s, his case was on appeal and his execution had been stayed. Blanck carved an imitation handgun from a block of wood, frightened the night jailer into giving up his keys and unlocked all the cell doors. Out of 19 inmates, 10 joined Blanck in his break for freedom, but Nordstrom and eight others stayed in their cells. Two of the escapees had second thoughts and ran immediately to Seattle Police headquarters and reported the escape. Four days later, Blanck was killed in a gunfight with a sheriff’s posse near Kent.

Finally, on June 19, 1901, the King County Superior Court, at the request of Prosecutor Walter S. Fulton (1873-1924), set Nordstrom’s seventh execution date for August 23, 1901, at the King County Courthouse. When U.S. District Court Judge Cornelius H. Hanford refused to entertain any further motions on the Nordstrom case, Lewis, in desperation, went to the King County Superior Court and asked for a commission of physicians to examine Nordstrom’s mental condition. On August 10, two medical experts examined Nordstrom, the second time in two years, and declared him to be sane. Dissatisfied with the result, Lewis asked the court for a competency hearing with a jury, which was denied. A six-man delegation, led by Lewis, appealed to Washington State Governor John Rankin Rogers (1838-1901) for commutation of the death sentence, but Rogers declined to interfere in the judgments of the courts. When Lewis argued Nordstrom “had only a child’s intellect at present,” Governor Rogers replied, “If a child were guilty of his crime, I would have him hanged” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer).

On August 21, two days before the hanging, Lewis, in a letter to the public, announced he had exhausted every means of saving Nordstrom from the gallows and withdrew from the case. Aside from being a remarkable piece of legal maneuvering, the case became nationally famous for being the longest stay of execution in judicial history. When he heard the news from friends, Nordstrom, who firmly believed Lewis would save him from hanging, broke down in tears.

The Hanging of Charles Nordstrom

By written invitation, the local press was on hand to cover the first execution at the new courthouse and the first public hanging in King County in 24 years (John Thompson was hanged in Renton on September 28, 1877, for the murder of Solomon Baxter). On the night before the execution, Sheriff Edward Cudihee (1853-1924) permitted reporters into the jail to recount Nordstrom’s final hours. The condemned man spent a restless night pacing his cell and chain-smoking cigars. At 6:15 a.m., Friday, August 23, 1901, King County Jailer James W. McLeod brought him a breakfast of beefsteak, buttered toast, fried potatoes, and coffee. Afterward, Nordstrom was shaved and dressed in a new black suit, with a white collar and a black necktie.

In an effort to avoid a dramatic scene, McLeod told Nordstrom the judge needed to see him. Guards marched him past the courtrooms, upstairs to the garret of the courthouse where a scaffold had been erected, but hidden behind a temporary partition. A cot had been place in a small, vaulted, brick archway and he was told to go sit and rest. Looking around suspiciously, he said in broken English, “This is not the courtroom. Where is the judge?” A guard replied, “He’ll be here pretty soon, Charley” (The Seattle Star). The answer seemed to placate Nordstrom, but as time passed, he became increasingly agitated. He asked the guards to see the scaffold, but they denied his request. Nordstrom was given a bag of candy and two women from the Salvation Army attempted to comfort him, but he began sobbing uncontrollably.

At 8:00 a.m., Sheriff Cudihee entered the alcove with the death warrant and began reading it to Nordstrom, who pretended not to understand. During the recitation, Nordstrom removed his coat, necktie, and collar, saying he was too hot. He was given a drink of whisky to calm his nerves and then Cudihee resumed reading. Thirty minutes later, he said “That’s all” and left the alcove.

Nordstrom was joined by Reverend E. Gustave Falk, pastor of the Swedish Methodist Episcopal Church and Reverend Martin Larson, pastor of the Swedish Evangelical Lutheran Church, who prayed with him in his native language. After the clergymen had withdrawn, a Salvation Army string quartet entered the alcove and began playing hymns while the condemned man sat on the cot weeping. In response to a reporter’s question, Reverend Larson said Nordstrom still maintained, as he had since his arrest, that he never killed anyone.

At 9:20 a.m., Sheriff Cudihee ordered a guard to admit those who had been invited to witness the execution into the garret. The assemblage consisted mostly of city and county officials, several physicians and attorneys, and representatives from the press. Among those present at the execution were Skagit County Sheriff Edwin Wells, Snohomish County Sheriff Peter Zimmerman, Whatcom County Sheriff William I. Brisbin, and Pierce County Sheriff John Hartman.

Shortly after 9:30 a.m., four guards led Nordstrom, struggling and crying for mercy, into the death chamber. He collapsed onto the floor and efforts to keep him standing on his feet were futile. Anticipating this problem, Sheriff Cudihee had a plank, with four leather straps attached, brought into the room. It required six guards to hold the prisoner down while straps were fastened across his chest, waist and arms, legs, and ankles. With Nordstrom immobilized, the guards hauled the plank up to the platform of the gallows. The plank was stood upright on the trap door and four guards held it in position. While Nordstrom babbled and cursed in Swedish, the executioner pulled a black hood over his head and adjusted the hangman’s noose around his neck. The trap was sprung at 9:49 a.m. and Nordstrom dropped five and one-half feet to his death. His body was taken down 13 minutes later and King County Coroner Charles E. Hoye pronounced him dead.

The following day, Dr. Hoye and his assistant Dr. Sherold F. Wiltsie conducted a post mortem examination of Nordstrom’s remains at the Seattle Undertaking Company, 1324 3rd Avenue. The autopsy was attended by several local physicians, who were interested in examining the victim’s brain. Although it weighed less than the “average” human brain, Dr. Hoye said: “It was the unanimous opinion of the physicians present at the examination that the man hanged was in his right mind” (The Seattle Star). (Today's neuroscience would consider any such conclusion from looking at a brain quite impossible.)

On Sunday, August 25, 1901, the funeral for Charles W. Nordstrom, officiated by Reverend Faulk, pastor of the Swedish ME Church, was held in the chapel at the Seattle Undertaking Company. His burial at the Lake View Cemetery was paid for by the Swedish Club of Seattle, but the grave lacks a headstone.

After the Execution

Four months after the execution, on December 26, 1901, Governor Rogers died. Lieutenant Governor Henry McBride (1856-1937) served the remainder of Rogers's term. Rogers was buried at Woodbine Cemetery in Puyallup. "Honest Tom" Humes, the judge who presided over the Nordstrom trial, was appointed mayor of Seattle in 1897, a position he held until 1904. In September 1904, he and his brother James went into the Tanana region of Alaska to prospect for gold. He died on November 9, 1904, in Fairbanks, Alaska of heart disease, less than eight months after leaving the office of mayor (March 21,1904) to Richard A. Ballinger. Humes and his wife Alma are buried in Seattle’s Lake View Cemetery. Edward Cudihee, who had been a Seattle Police detective (1890-1900) and served a total of three two-year terms as King County Sheriff (1901-1905 and 1913-1915) had become famous for cheating death when he arrested murderer Tom Blanck in 1894 and for his part in doggedly pursuing notorious outlaw Harry Tracy in 1902.

The first capital punishment statute, enacted by the Washington State Territorial Legislature in 1854, called for the mandatory death sentence of persons convicted of first-degree murder. The first legal execution in King County took place in Renton on September 28, 1877, with the hanging of John Thompson. The Washington State Legislature amended the capital punishment statute in 1901, requiring that executions take place at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla. The first execution at the penitentiary took place on May 6, 1904, with the hanging of Zenon "James" Champoux for the murder of Lottie Brace in Seattle in 1902.

Nordstrom was the first, but not the last, prisoner to be executed in the King County Courthouse. That dubious distinction went to William Seaton, who was hanged on January 3, 1902, for the murder of his uncle and the attempted murder of his sister and two step-daughters with an ax.