On April 26, 1951, Robert R. Johnson and Luther J. Moore, inmates at the Washington State Reformatory in Monroe (Snohomish County), bludgeon to death power-plant engineer Benjamin Bert Marshall (1888-1951) with saps made from pieces of steam hose and attempt to escape from the compound using a makeshift ladder. Just as Johnson reaches the top of the 30-foot west wall, however, the ladder breaks apart. Moore falls back inside and is soon captured by a guard. Johnson hides overnight in a field close to the main reformatory building and surrenders to guards early the next morning. At a trial in Snohomish County Superior Court, both inmates are found guilty of first-degree murder. When the jury votes against the death penalty, the mandatory sentence of life imprisonment is imposed and both defendants are sent to the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla.

From Trusty to Not

The Washington State Reformatory, opened in 1910, is located in Monroe, approximately 20 miles east of Everett. Now called the Washington State Reformatory Unit (WSRU), it is part of the Monroe Correctional Complex, which is composed of four separate units with a total population of 2,500 male inmates and custody levels ranging from maximum to minimum. The reformatory unit houses up to 875 inmates in two large cell blocks that are the most prominent feature of this historical building. The 11-acre compound is surrounded by 30-foot-high brick wall with six guard towers strategically placed to monitor activity inside the compound.

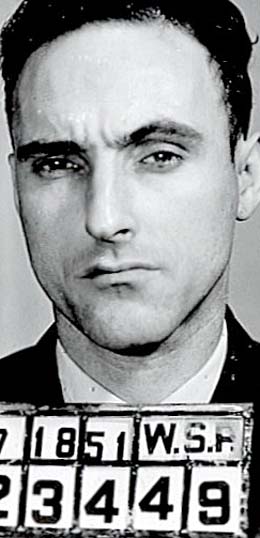

Robert Richard Johnson, age 32, had been convicted of burglary in King County Superior Court in April 1939. He and two accomplices broke into West Seattle High School and stole musical instruments. Johnson, sent to the Washington State Reformatory for a term of not more than 15 years, was paroled in May 1940. Between 1941 and 1950, however, he was arrested three times for parole violations and finally returned to the reformatory to serve out the remainder his sentence.

Luther John Moore, age 26, had been convicted of grand larceny (theft of property valued at more than $500) in Grant County Superior Court in October 1950. He stole a truck parked outside a warehouse in Moses Lake and was arrested by the Washington State Patrol. Moore was sentenced to a term of not more than 15 years at the Washington State Reformatory. Neither prisoner was believed to be dangerous and both had been granted trusty status.

The Crime and Its Aftermath

At approximately 9:00 p.m. on Thursday, April 26, 1951, engineer Benjamin Bert Marshall, age 62, was supervising trusties working in the power plant, which provided emergency electricity for the reformatory. Johnson and Moore, assigned to a maintenance crew, had been overhauling a pump in the auxiliary engine room and Moore asked Marshall to inspect the job. When he arrived, they bludgeoned Marshall on the head with saps made from sections of steam hose into which metal bolts had been inserted. The two men bound his hands and feet with ignition wiring ripped from a diesel engine, stuffed a gag into his mouth, and then stole his wallet and wristwatch.

Johnson and Moore, who had been working on a plan to escape from the reformatory for three days, had convinced Marshall that a vacuum pump on a steam compressor needed reconditioning. They volunteered to work on the project after hours so they could escape under the cover of darkness. While disassembling the pump, the men fashioned the two saps and several sections of a makeshift scaling ladder, made from half-inch steel pipe and fittings, hiding them behind a large tool box in the auxiliary engine room. After beating Marshall unconscious, Johnson and Moore quickly assembled the ladder sections and attached it to the west wall of the compound behind the power plant, midway between two unmanned guard towers.

The two began climbing the ladder together and just as Johnson reached the top, it broke apart under their combined weight. Johnson made it over the wall, but Moore, who was within three feet of the top, tumbled back inside the compound and limped back toward the power plant. Johnson made his way to the reformatory’s water tank, a place where they agreed to meet if they became separated. But then the prison whistle blew, signifying an escape, and Johnson ran off into a field of brush. He got lost and disoriented in the dark and eventually hid in a briar patch. Johnson soon realized he was not likely to escape and decided to give himself up in the morning.

At approximately 9:15 p.m., trusty Francis Baker, age 19, who had been working inside the boiler room as a fireman, found Marshall lying unconscious on the basement floor in a pool of his own blood and contacted the guard house. Officer Walter G. Brown, who had seen Moore slip inside the power plant partially dressed, caught him taking a shower. He denied being a party either to Marshall’s beating or an escape attempt. Moore claimed he saw Johnson standing over Marshall’s body and that Johnson attacked him, but he managed to escape into the boiler room.

Within minutes after the escape whistle blew, 150 reformatory guards and Snohomish County Sheriff’s deputies surrounded Monroe, blocking every road and checking every vehicle. Superintendent Earl H. Lee (1886-1964) immediately broadcast a state-wide alert for the escaped convict. Police officers from Everett, Marysville, and Snohomish as well as large contingent from the Washington State Patrol rushed to the area to help search for the escapee.

Attendants at the infirmary attempted to stabilize Marshall with infusions of plasma and an ambulance rushed him to Monroe General Hospital (now Valley General Hospital). But it was too late. He died 45 minutes later from a compound skull fracture.

At 6:30 a.m. on Friday, April 27, 1951, Johnson emerged from a field across the road from the main reformatory building. Minus his shirt and shoes and with his hands in the air, he surrendered to reformatory guards Clyde Parker and Ed Olson. Once in custody, Johnson told Superintendent Lee, “Write it out, I’ll sign it” (The Everett Daily Herald). Then he proceeded to give Lee, Snohomish County Prosecutor Phillip G. Sheridan and Snohomish County Sheriff Thomas V. Warnock a detailed confession, implicating Moore in the escape attempt. Johnson said it was his idea knock Marshall unconscious, to give them more time to escape, but they had not intended to kill him. Had he known Marshall was dead, Johnson said he would not have given up without a fight. Moore vehemently denied he was Johnson’s accomplice and refused to make a statement.

Friday afternoon, Prosecutor Sheridan charged Johnson and Moore in Justice Court with the murder of Ben Marshall. The prisoners, who had been in isolation cells at the reformatory, were booked into the Snohomish County jail on May 3, 1951. On Saturday, May 5, Prosecutor Sheridan filed an information in Snohomish County Superior Court, charging Johnson and Moore with first-degree murder and murder while in commission of robbery, either act qualifying the defendants for the death penalty.

Funeral services for Ben Marshall were held in Everett at the Purdy and Walters Funeral Home, 1702 Pacific Avenue, on Monday afternoon, April 30, 1951. He was buried in the Evergreen Cemetery, 4504 Broadway, Everett. Marshall, who had been employed at the reformatory for several years, was survived by his wife, Hazel, and two adult children, Ardis and Blaine.

Arraignment and Trial

Johnson was arraigned before Judge Charles R. Denney on Saturday, May 12, and pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity. The court appointed William Lanning, a Seattle attorney, to represent Johnson. Lewis A. Bell, an Everett attorney, was appointed to represent Moore.

Moore was arraigned before Judge Denney on Friday, May 18, and stood mute. A plea of not guilty was entered by the court on his behalf, standard practice in a death-penalty case. Later, Moore changed his plea to not guilty by reason of insanity. On May 24, Judge Denney denied a defense motion for a stay of proceeding and for separate trials and ordered the trial to commence on Monday morning, June 18, 1951.

For a potential death-penalty case, the trial was relatively short. After two days of questioning, a jury of three women and eight men plus one alternate was impaneled and sworn in. Opening statements and testimony commenced on Wednesday morning, June 20. Prosecutor Sheridan outlined the state’s case against the defendants. He told the jury Johnson and Moore qualified for the death penalty because Marshall’s murder was premeditated and it was committed while engaged in an act of robbery. The murder weapons and the ladder had been made and hidden prior to the escape attempt and the victim’s wallet and wristwatch were stolen from his body. Attorneys for Johnson and Moore told the jury that Marshall’s death was not premeditated murder, but an unintended accident for which they didn’t deserve to die.

The prosecution called 33 witnesses including two recently paroled inmates who had been working at the power plant on the night of Ben Marshall’s murder. They testified that Moore came into the boiler room about 9:15 p.m. and said the engineer had been injured. Moore was extremely nervous, had blood on his face and asked for help getting over the wall. Moments later, Moore opened the door to the furnace and tossed in his shirt. Then he stripped off the rest of his clothes and went into the shower room.

Officer Brown testified that he detained Moore in the shower room and took him to the main building for questioning. Robert Richards, attendant in charge of the infirmary, testified that Moore had spots of blood on his head and face, which Moore claimed came from a fight with Johnson at the power station. But Richards said Moore was uninjured, except for his foot which he injured falling off the ladder.

After laying the groundwork for the murder charges against Moore, the prosecution proceeded with its case against Johnson by introducing his signed confession describing the details of the assault and escape. The prosecution also succeeded in introducing a confession signed by Moore six days after the murder in which he admitted taking Marshall’s wallet and wristwatch. On Monday afternoon, June 25, after five days of direct testimony, the prosecution rested its case.

On Tuesday morning, June 26, Luther Moore took the stand to testify in his own defense. Although his testimony was often confusing and contradictory, Moore’s story was remarkably similar to the scenario presented by the prosecution. He admitted robbing Marshall but claimed he had not struck him; he told Johnson to do it. Later Moore testified: “I hit him twice. I told Johnson it wouldn’t kill him to hit him on the side of his head. I hit him again at the same place a little harder” (The Everett Daily Herald). He concluded his testimony by repeating they had not intended to kill Marshall, just buy enough time to escape undetected.

Johnson decided not to take the stand. Defense attorney Lanning called only two witnesses: Johnson’s mother, who testified that Robert had been mentally incompetent ever since being hit by a car in 1929, and a clerk from the Seattle Public Health Department to authenticate Johnson’s hospital records. The defense offered no expert testimony to substantiate either defendants’ plea of insanity. On a motion by Prosecutor Sheridan, Judge Denney had the testimony of the two defense witnesses and insanity pleas of both defendants stricken from the record.

The defense rested its case on Tuesday afternoon and closing arguments began on Wednesday morning. In his summation, Prosecutor Sheridan asked for the death penalty, stating there was conclusive evidence of first-degree murder in connection with Marshall’s assault and robbery. “If I did not ask that the death penalty be inflicted in this case, I would be delinquent in my duty as prosecuting attorney” (The Everett Daily Herald). Attorneys Bell and Lanning basically had no defense arguments and pleaded for a verdict of second-degree murder or manslaughter.

A Life Sentence

The trial concluded Wednesday afternoon, June 27, and the case went to the jury at 3:35 p.m. After only five hours of deliberation, the bailiff told Judge Denney the jury had reached a verdict and court was reconvened at 10:00 p.m. The jury foreman, Loren H. Bradbury, announced that both Johnson and Moore were found guilty of first-degree murder, but the jury voted not to impose the death penalty, making life imprisonment mandatory. Prosecutor Sheridan expressed his satisfaction with the verdict, remarking it was jury’s responsibility to decide the penalty.

During sentencing, Judge Denney ordered that Johnson, who had been scheduled for release on May 23, 1955, finish serving his sentence for burglary before beginning his life sentence for first-degree murder. He was transferred directly from the Snohomish County jail to the Washington State Penitentiary at Walla Walla.

Judge Denney likewise ordered that Moore, who had been scheduled for release October 1, 1965, finish his sentence for grand larceny before serving his life sentence. Moore, however, had been behaving abnormally during the final days of his trial, constantly muttering to himself and disrupting the court proceedings with loud shouts and laughter. Judge Denney ordered him transferred to the Northern State Hospital at Sedro-Woolley for mental evaluation. The psychiatrists there apparently determined Moore was no more psychotic than most prison inmates and on October 4, 1951, he was transferred to the Washington State Penitentiary.

On Friday, April 25, 2014, after a 63-year delay, a memorial ceremony was held at the Monroe Correctional Complex to honor Benjamin Marshall and place his name on the newly created Walk of Remembrance Memorial. He was the first employee at Monroe to be killed in the line of duty.