Point Roberts (Whatcom County) is a 4.9-square-mile unincorporated American exclave located in the southern part of Canada's Tsawwassen Peninsula. Although Point Roberts is part of the United States, it is not physically connected to the United States. Reaching it requires a 14-mile boat trip from the Canadian border crossing at Blaine, or a drive nearly twice that far through Canada. In its early years Point Roberts was an unused military reserve, almost a no-man's land of sorts, but by 1900 the reserve was gone and an active fishing industry was developing there. Eventually the fishing faded and in the past half-century Point Roberts has become a unique recreational community with a strong Canadian influence.

Early Years

Point Roberts was a favored fishing spot for Native American bands and tribes -- such as the Cowichan, Lummi, Saanich, and Semiahmoo -- for thousands of years before the first European explorers spied the point in 1791. Indians set up summer camps there every year when the salmon were running, though due to its exposure few lived there year-round.

In 1791, Spanish explorer Francisco Eliza (1759-1825) mistook Point Roberts for an island and named it Isla de Zepeda. The following year two other Spanish explorers, Dionisio Galiano (1760-1825) and Cayetano Valdes (1767-1835), realized Eliza’s mistake and renamed the spot Punta Cepeda. But at the same time British explorer George Vancouver (1758-1798) passed through the area (actually meeting up with the Spanish explorers) and gave Point Roberts its present name as a tribute to his friend Henry Roberts, who had been Vancouver’s predecessor in command of the British expedition.

In 1846 Great Britain and the United States signed the Oregon Treaty, establishing the 49th parallel as the boundary between United States territory to the south and British territory to the north, from the Strait of Georgia east to the Continental Divide in northwestern Montana (an exception was made for Vancouver Island, which became entirely British). But it turned out that the lower part of the Tsawwassen Peninsula dipped down into the United States, and though there has been occasional talk over the years, sometimes serious, more often not, about making Point Roberts part of Canada, it hasn’t happened.

The Fraser River Gold Rush in 1858 set off a stampede of prospectors bound for the lower mainland of British Columbia, and Point Roberts became a jumping-off place for some of them. A little village sprang up on the western shore of the peninsula, but almost as quickly withered away a year later when the gold rush turned to dust. Later that same year, in September 1859, the United States established a military reserve at Point Roberts, though no military personnel or equipment ever went there. Instead, development essentially froze for the next three decades.

Point Roberts evolved into almost a no-man’s land, a dangerous haven for smugglers and otherwise lawless men, where you could find trouble easily if you wanted. During the 1870s, despite the risks, a few homesteaders moved to the point. John Harris (d. 1883) -- believed to be the first permanent settler in Point Roberts -- arrived about 1873 and raised cattle there; a few other settlers arrived later in the 1870s, and in 1879 the Pacific Fishing Company established the first store and trading point.

Fishing and Farming

In 1892 the U.S. government vacated the reserve, clearing the way for real development, although Point Roberts was not fully opened to homesteading until 1908 (with the exception of its southwestern corner, which was set aside for a lighthouse station that was never built). A town formed in the western part, and in its earliest years attracted a significant number of people of Icelandic descent. Many of these families had been living in Victoria, B.C., before coming to Point Roberts in the 1890s in search of better economic opportunities. Some farmed and others worked for the canneries. The little community within a community grew and by 1904 there were 93 residents of Icelandic descent living in Point Roberts, representing about half of the town’s population. In 1904 Point Roberts also had 23 houses, two general stores, a hotel, a post office, and a saloon.

On the southeastern shore, Edmund Wadhams (1833-1900) built a cannery in 1893 at what is today (2009) Lily Point. Late that year he sold the cannery to the Alaska Packers Association (APA), which assumed management operations by the spring of 1894. On the western shore, about half a mile south of the Canadian border, the George and Barker Packing Company commenced operations in 1900. Various entrepreneurs set up fish traps in the waters offshore, providing residents with another source of employment. Small farms also developed on the point, though the land was not particularly favorable for farming.

During the 1910s road construction accelerated. The first road linking Point Roberts with Canada, now known as Tyee Drive, was finished by 1919, which led to Point Robert’s first United States border “station” -- a tent tossed over a fallen log, staffed only a few times a month. Finally, in 1934, a real customs building, consisting of two rooms, was built at the border crossing. A second border crossing existed closer to Maple Beach, east of the primary crossing, during the 1960s and into the 1970s, but closed in 1975.

By the late 1910s the annual salmon runs in the waters around Point Roberts were becoming depleted. This had a direct impact on the fishing industry: The APA closed its cannery in 1917, and George and Barker closed its cannery in 1929. Then in 1934 fish traps were outlawed in Washington state, sounding the death knell for the fishing industry at Point Roberts. Some efforts at farming continued, but thanks to the poor quality of the soil, these were not successful, and by the 1950s most of the farms had disappeared. To further add to the community’s woes, the grade school that had operated since 1893 was closed in 1963 and its students had to be bused to Blaine, more than 25 miles away. (In 1992 a school for kindergarten to second grade reopened.)

A Canadian Change

During the 1950s a great change came to Point Roberts from its neighbors to the north. Canadians had bought land on the point from its early days, but in 1953 they were officially given the right by state statute to purchase land in Washington state. In 1959 a four-lane tunnel opened under the south arm of the Fraser River at Deas Island south of Vancouver, making it easy for Vancouverites to travel to Point Roberts. These events led to an influx of Canadians purchasing land from broke farmers, and by 1970 more than half of the town’s permanent residents were Canadian. That figure has lessened slightly to 40 percent today, but Canadians still own nearly half of the property in Point Roberts.

Other changes followed, turning Point Roberts into the recreational community that we know today. Lighthouse Marine Park, on the southwestern tip of the point, was dedicated in 1973. Named for the lighthouse that was never built, it is a pleasant 21-acre park that is a favored spot to view Orca whales in the summer. And just east of the park, the 900-berth Point Roberts Marina, capable of housing boats up to 60 feet long, opened in 1977.

Point Roberts Today

Point Roberts today accurately touts itself as a uniquely American community. But to a casual observer dropping in for the day, it feels as much Canadian as it does American. True, the speed limit signs are in miles per hour as opposed to Canadian kilometers, but the gas station price signs are in Canadian liters (sometimes American gallons are displayed on an adjacent sign), the accents of the Point Roberts townspeople tend to carry a Canadian inflection, and if you make a purchase the teller may assume you’re paying in Canadian money unless you advise otherwise. But dual currencies are not a problem in Point Roberts. The cash registers have two drawers in one -- one side dispenses Canadian funds, the other side American. The registers are said to be updated daily to properly calculate the current exchange rate.

The 2000 U.S. Census recorded Point Roberts’ population at 1,308, but when vacationers arrive during the summer it more than triples. As has been the case for much, if not all, of the past half-century, the median age of its residents was significantly higher in 2000 than that of the U.S. as a whole; at 43.2 years, the median age was eight years higher in Point Roberts than the U.S. median. And its population was nearly 95 percent Caucasian, far higher than the 75 percent figure in the rest of the country. Due in no small part to the border crossing, its crime rate is remarkably low, which leads residents to proudly describe Point Roberts as the ultimate gated community.

But apart from the official crossing itself, the border at Point Roberts is marked merely with shrubs or trees planted closely together as sort of a line of demarcation. In some places there are no shrubs or trees at all and you can simply walk across the border. Yes, there are cameras surveying the border, but it is not hard for a motivated individual to slip into Canada undetected.

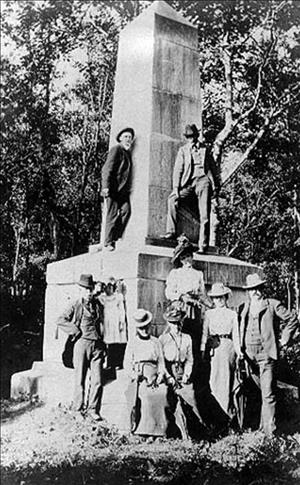

Point Roberts has no downtown. Tyee Street is the main drag and has several gas stations and an International Market Place. Gulf Road, leading west from Tyee north of the marina, boasts art galleries and real-estate agencies. But it is perhaps the four corners of Point Roberts that are the most interesting to visit. The southwestern corner has Lighthouse Park. The northwestern corner has the international boundary marker, placed there shortly after the western portion of the boundary survey was finished in 1861. The northeastern corner is the home of Maple Beach, with a remarkable beach that stretches half a mile out into Boundary Bay when the tide goes out, and with eye-catching views of the highrises of the Vancouver suburbs to the north. Downtown Vancouver is barely 20 miles away.

But Lily Point at the southeastern corner of Point Roberts should take honors for the community’s most scenic spot. You can walk to a viewpoint atop a 200-foot cliff and (if it’s clear) gaze out at a valhalla of water, mountains, beach, and sky. Or head east down a short but steep trail to the water itself. This is the former site of the APA cannery, and traces of the cannery still remain on the beach; a few pilings here, an odd rusted-out piece of machinery there. But walk a few hundred feet and that will be behind you, and even on a sunny summer day, don’t be surprised if you have the beach nearly to yourself. If you’re lucky you may see an eagle overhead to complete the tableau, but even if not, you’ll be smiling when you leave.