On July 11, 1811, Canadian explorer David Thompson (1770-1857) reaches Celilo Falls on the Columbia River after a historic voyage downriver from Kettle Falls. Over the next three days, Thompson surveys Celilo Falls, The Dalles, and Cascades Rapids as he continues down the river. In addition to his scientific work as a geographer, Thompson is the fur agent in charge of the Columbia Department of the North West Company of Canada. He is on a mission to determine whether the Columbia is navigable from its upper reaches to the sea and whether it will provide a viable trade route for the fur company. Thompson is traveling in a cedar plank canoe manned by eight French Canadian and Iroquois paddlers.

July 11: A Strong Rapid

After camping near the mouth of the John Day River on the evening of July 10, Thompson and his voyageurs set off at 5 a.m. on July 11 into a steady headwind. They stopped to visit a village of 63 families, then continued down the Columbia. By midmorning they were tossing through standing waves and almost collided with protruding rocks as they approached Celilo Falls (now submerged beneath the reservoir of The Dalles Dam). The river was so swollen with spring runoff that the Nor'Westers were able to line their way along the left side of the channel without a portage. Over the next six miles, Thompson noted "many strong Rapids, some of them required all our skill to avoid being upset, or sunk by the waves; we passed two Villages but could not put ashore" (Thompson, Travels, iii.271).

In mid-afternoon the current slackened enough for the voyageurs to beach the canoe near a large village that Thompson estimated held 300 families. The inhabitants greeted the visitors with a dance, but because his supply of tobacco was running low, Thompson invited only a few of the most "respectable" men to smoke with him. He learned that they had already formed an opinion of Europeans from the ships that traded near the mouth of the river. "These people have some knowledge of white Men," he wrote, "and so far it was not in our favor" (Thompson, Travels, ii. 247).

This village, situated between the upper and lower Dalles, marked a rough boundary between the Sahaptin and Upper Chinookan language families, and between Plateau and Coastal cultures. The Sahaptin interpreter who had escorted the Nor'Westers down the mid-Columbia departed to return to his home upstream. "I paid him as well as I could for his services, which were of great service to us," Thompson remarked (Thompson, Notebook 27).

The villagers warned Thompson that a dangerous series of unnavigable "Dalles and Falls" lay ahead. He made arrangements to hire horses to portage his baggage the next day.

July 12: The Dalles

"July 12. Friday. A fine Morng but windy. Early got up & waited the promised Horses to be lent us to carry the Things over the Portage, but not coming, we carried them a full Mile to a small Bay" (Thompson, Notebook 27).

This mile-long portage led around the lower Dalles (site of the present-day Dalles Dam), where the river was forced through a steep basalt canyon. "Imagination can hardly form an idea of the working of this immense body of water under such a compression, raging and hissing, as if alive," Thompson wrote (Travels, iii. 272). In a large eddy at the base of the falls, harbor seals cavorted in the waves and chased migrating salmon. The voyageurs "fired a few Shots without effect," then stopped on an island to boil fish for breakfast and re-gum the canoe while Thompson took observations for the latitude and longitude of this important landmark.

About 15 miles farther downstream, green grass and scattered deciduous trees announced "a most agreeable change from bare banks and monotonous plains" (Thompson, Travels, iii. 273). Floating through the Columbia Gorge, the Nor'Westers were immersed in veils of hanging clouds and surrounded by gigantic trees and luxuriant vegetation. Opposite present-day Hood River, the white summits of Mount Hood and Mount Adams came into view. When they met two Chinook men in a canoe, Thompson relied on sign language to communicate.

The Waw thlar lars

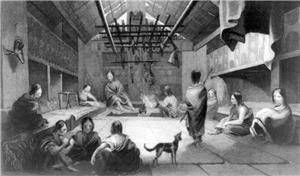

Upon reaching the Chinookan men's village on the north shore of the river a short time later, the Nor'Westers stopped to smoke with the chief, who invited them to camp nearby. The villagers, whose name Thompson recorded as "Waw thlar lar," built large lodges from logs, "the inside clean and well arranged, separate bed places fastened to the walls, and raised about three feet above the floor" (Thompson, Travels, iii. 274). The people were in the process of preserving filleted salmon, which hung from poles fixed to the ceiling so as to receive the full benefit of smoke from a fire that was kept burning inside the lodge. Thompson visited for about an hour in the lodge of the chief, who knew "many english words he had earned from the ships when trading with them, some of them not the best" (Travels, iii.274).

This group of Upper Chinookans who lived along the series of rapids known as the Cascades of the Columbia later came to be known as the Cascade Indians, and Thompson was insightful in noting that they spoke a different dialect than their relations a short distance upriver. On their way downstream in October 1805, Lewis and Clark had stopped at a "town" near the head of the Cascades, probably the same village visited by Thompson, but the American party passed through after the fall salmon runs and therefore did not witness the residents in the midst of catching and preserving salmon for winter use.

July 13: The Cascades of the Columbia

The next morning (July 13), the Nor'Westers faced another portage around the Cascade rapids (the site of present-day Bonneville Dam). While the villagers helped the voyageurs carry their canoe and cargo, Thompson recorded several words of the Chinook language. After relaunching their boat at the base of the rapids, the Nor'Westers paddled through the calmer waters of the lower Columbia, then camped a short distance upstream from Point Vancouver, a landmark that Thompson recognized from George Vancouver's account of his 1792 voyage to the Pacific Northwest.