The Third Ministerial Conference of the World Trade Organization (WTO), held in Seattle from November 30 to December 3, 1999, brought together trade ministers and other officials from the WTO's 135 member countries in an attempt, which proved unsuccessful, to agree on the issues and agenda for a new round of negotiations aimed at further deregulating international trade, particularly in such controversial areas as agriculture, services, and intellectual property. It also brought tens of thousands of protestors to the city's downtown streets. Most governments around the world, leading multinational corporations, and virtually all of Washington state's political and business leaders supported the WTO and "free trade," which they argued benefited society by promoting economic growth. However, internationally and locally labor unions, environmental groups, and activists for many other causes increasingly condemned the WTO for favoring corporate interests over social and environmental concerns. Part 1 of this two-part essay describes the history of the WTO and the many issues and controversies that divided supporters and opponents of free trade in Washington state and around the world and inspired the week of protests that became known as the "battle in Seattle."

International Issues, Local Connections

Although the issues and debates that swirled around the WTO were world-wide in scope, and both conference attendees and protestors came to Seattle from across the globe, many of the fundamental conflicts and contradictions were epitomized in the city and state chosen to host the first ministerial trade meeting held in the United States. On one hand, the city of Seattle and state of Washington were (and remain) more dependent on international trade than almost any other part of the country. The state's largest corporations, including Boeing, Microsoft, and Weyerhaeuser, all major exporters, strongly supported free trade and the WTO and were major sponsors of the conference in Seattle. State agricultural producers were also heavily dependent on international markets.

Not surprisingly the state's political leadership, from Governor Gary Locke (b. 1950) -- who would later serve as U.S. Commerce Secretary -- on down, virtually unanimously lined up in favor of free trade and the WTO. Seattle Mayor Paul Schell (1937-2014) and most other local officials joined or supported the effort, led by Pat Davis, president of the Washington Council on International Trade and a Port of Seattle Commissioner, that in January 1999 won Seattle the honor (a dubious one at best as it turned out) of hosting the WTO ministerial conference. The position of the state and local political establishment mirrored that of the national political leadership, where free trade enjoyed substantial bipartisan support and both Republican and Democratic administrations pushed for new trade agreements. Politicians, corporations, trade economists, and other advocates for free trade argued that eliminating protective tariffs and other laws or regulations that restricted international trade promoted economic growth and helped reduce poverty, especially in the developing world, by creating new jobs.

On the other hand, labor unions and environmentalists, two groups that saw many negative consequences arising from unfettered free trade and were among the most vocal critics of the WTO, also had deep roots and a strong presence in Seattle and throughout the northwest. Efforts to organize Washington workers date back to the Knights of Labor in the 1880s. Unions and their struggle to win better pay and working conditions played a prominent role in state history throughout the twentieth century, from the radical Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), known as Wobblies, organizing timber workers in the century's early years through the Seattle General Strike of 1919 to the influence wielded for many years by unions such as the Teamsters and the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union (ILWU). Teamsters, longshore workers, and even a resurgent IWW all figured prominently in the Seattle WTO protests.

Environmental activism likewise has a long history in the region, from early conservationists advocating the creation of national forests and parks in the area to more recent activists fighting to save old growth forests, wild rivers, and endangered species. Direct action protestors attempting to block logging operations in Northwest forests pioneered many of the techniques later used successfully to block the streets around the WTO meeting.

Teamsters and Turtles

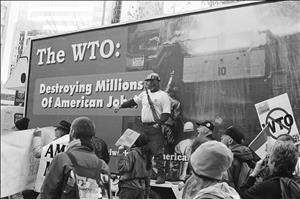

Although environmentalists and workers have not always been seen as allies and at times, as in clashes over logging, were active opponents, unions and environmental groups, nationally as in Washington, found common ground in their opposition to the WTO. Their similar demands that standards for environmental protection and for workers' rights be incorporated into trade agreements and enforced by the WTO grew out of a common understanding that free trade impacted all aspects of society and directly affected, often adversely, their interests. Workers complained that manufacturing jobs shifted to countries with lower wages and fewer rights and environmentalists objected when local environmental regulations were struck down as violations of free trade agreements. Thus leaders from the Teamsters, United Steelworkers, and other unions spent months working with environmental and consumer activists in a coalition brought together by Lori Wallach and Mike Dolan from the Ralph Nader group Public Citizen -- a group some of the union participants previously had little use for -- to plan and coordinate the massive rallies and marches that brought large crowds of protestors to the streets of Seattle. The success, and novelty, of the alliance was reflected in the often-repeated reference to "Teamsters and turtles" marching together (several hundred protestors donned sea turtle costumes to protest a WTO ruling seen as harming the endangered species).

Opposition to the WTO may have united unions and environmentalists, but it divided them from Democratic Party advocates for free trade like Governor Locke and President Bill Clinton (b. 1946), even though they otherwise represented significant portions of the Democratic base. Clinton, for one, attempted to bridge the gap by calling on the WTO to address worker and environmental concerns in the upcoming negotiations. In addition, the president openly encouraged WTO opponents to come to Seattle and make their views known. Speaking to workers at a Harley Davidson factory shortly before the conference in Seattle, Clinton said:

"Every group in the world with an ax to grind is going to Seattle. I told them all I wanted them to come ... . I want everybody to get this all out of their system and say their piece. And I want us to have a huge debate about this" (Postman, "Everyone has…").

Seattle officials, led by Mayor Schell, also repeatedly stated that the city would welcome not only the WTO conference but also all who came to protest peacefully against it. As it turned out, tens of thousands from around the country and the world, representing not just unions and environmental groups but a huge range of causes across the political spectrum, took up the invitation to protest in Seattle.

The World Trade Organization

The reasons that so many objected to the work of what might have seemed an obscure international agency were rooted in the history of that agency. At the time of its meeting in Seattle, the World Trade Organization had been around for less than five years. It was created in 1994 (effective in 1995) to succeed an earlier international trade body, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). The GATT was one of several international economic organizations, along with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, created in the aftermath of World War II to promote recovery and economic growth following the war and the Great Depression that preceded it. During the Depression, many countries had responded to the economic downturn by imposing high tariffs on foreign imports and other measures that limited or regulated international trade. Postwar leaders in the U.S. and Europe believed that these protectionist measures had further damaged the economy and they designed the GATT to reduce tariffs and other barriers to what they termed "free trade."

From its formation in 1948 through 1993, members of the GATT (which grew to include nearly 100 countries), engaged in eight rounds of negotiations resulting in numerous agreements reducing tariffs and otherwise deregulating trade in industrial products. Despite its importance to diplomats and economists, the GATT remained relatively obscure through its nearly 50 years of existence while its successor, the WTO, quickly became a lightning rod for criticism.

This was due in part to two key changes that substantially expanded the influence of the WTO compared to its predecessor. First, while the GATT had focused largely on trade in manufactured goods, the WTO was given additional authority to address other economic sectors such as services, intellectual property, and agriculture. Second, and even more alarming to many, the WTO, unlike its predecessor, had the legal authority to require changes in national laws or regulations deemed to violate trade agreements. Both changes served to significantly ramp up controversy over free trade negotiations.

Divisive Subjects

For starters, some of the new areas subject to WTO rules, agriculture in particular, engendered considerable controversy not only among outside critics but also within the WTO itself, as the Seattle meeting would demonstrate. Even among leaders committed to free trade, there were sharp differences over farm subsidies. And free trade critics denounced the "globalization" of agriculture for devastating small farmers and destabilizing rural communities in developing countries when cheap imports from corporate agricultural producers flooded their markets; for jeopardizing local practices and regulations that protected the environment, food safety, and animal welfare; and for promoting genetically engineered crops, among other concerns.

In addition, by asserting authority to impose "free trade" rules in areas, such as protection of intellectual property, that extended far beyond the elimination of tariffs on manufactured goods, the WTO opened the door to critics, like unions who argued that WTO agreements and rules should also address unfair labor practices such as child labor and restrictions on union organizing. Free trade advocates usually answered the unions' demands by arguing that the WTO focused exclusively on trade and that labor standards were better addressed by other organizations, particularly the International Labor Organization (ILO), a United Nations agency. However, after WTO agreements required developing countries to enforce strict copyright protections, at the request of multinational corporations concerned about piracy of computer software, music, movies, and other copyrighted material, it was harder for free trade supporters to contend that "trade" agreements protecting intellectual property should not also protect workers' rights.

The WTO's enforcement of corporate intellectual property rights while arguing that labor standards -- as well as environmental standards, human rights protections, and other issues that advocates wanted the agency to enforce -- should be dealt with elsewhere led critics to accuse it of favoring corporate interests over social and environmental concerns. Opponents made the point that the WTO, which established and enforced hundreds of complex, detailed rules addressing intellectual property and many other subjects, didn't promote truly free trade at all. One critique asserted that "in fact, the WTO's 700-plus pages of rules set out a comprehensive system of corporate-managed trade" (A Citizen's Guide ..., p. 1).

However, opposition to including labor and environmental standards in the WTO was not confined to corporations and WTO officials. In the developing countries of Asia, Africa, and Latin America non-governmental groups, activists, and intellectuals, many quite skeptical of the free trade agenda, joined their national governments in denouncing efforts to link labor or environmental standards to trade agreements, just as they had objected to the successful push to impose intellectual property protection in those agreements. In their view, requiring developing countries to meet First World standards in any of these areas functioned as another form of protectionism, letting large developed countries reject imports from the developing world while gaining full access to markets in that world.

Too Much Power?

While the WTO's greater involvement in areas such as agriculture and intellectual property increased the issues in dispute, its new authority to override individual nations' law really galvanized critics. The GATT had not been able to force member countries to abide by agreements if they chose to ignore them in a particular case. In contrast, the WTO had what its supporters called effective dispute resolution and enforcement powers. Under that dispute settlement system, which was legally binding on all members, one country could challenge another country's laws or regulations as being in violation of trade rules, and the dispute would be heard by a panel of three designated experts, with appeal possible to an Appellate Body. If a violation was found, the country in violation was required to either implement the WTO decision by changing its regulations, pay compensation to the complaining country, or be subject to retaliatory tariffs.

The WTO's ability to overrule local law caused international outrage among all sorts of groups whose views had little else in common. Small farmers, indigenous leaders, and other activists in developing countries complained that the WTO favored multi-national corporations over the interests of their communities. Many in Europe feared that the WTO would lead to dismantling their social safety net and environmental and consumer protections.

In the United States, critics across the political spectrum condemned the WTO. On the right, conservative Pat Buchanan (b. 1938), who was running in the 2000 presidential race on the Reform Party ticket and made an appearance in Seattle during the WTO conference, campaigned in favor of trade protectionism and accused the WTO of threatening U.S. sovereignty. On the left, activists complained that WTO rulings had undermined U.S. environmental protections.

In one case that was notorious among critics (and inspired the sea turtle costumes worn in Seattle), the WTO ruled in favor of several countries challenging U.S. endangered species regulations that restricted imports of shrimp caught using methods that killed endangered sea turtles. But environmentalists and food safety activists in the U.S. and Europe were equally angered when a challenge by the U.S. (and Canada) resulted in a WTO ruling against a European Union regulation that prevented the importation of beef from cattle treated with bovine growth hormone.

Behind Closed Doors

Based on these precedents, critics feared that the WTO threatened other laws and regulations in many countries that were designed to protect the environment, consumers, workers, or human rights or otherwise benefit society, if those laws were found to interfere with free trade agreements. These fears were exacerbated by what many saw as the WTO's secretive and undemocratic decision-making procedures. Critics, including some Third World governments, complained that the major industrial powers negotiated privately on key issues and then insisted that the remaining member countries accept their position. They also objected to the dispute settlement process, where unelected bureaucrats on the expert and appeal panels met behind closed doors -- only the disputing parties could participate -- but made decisions, as in the sea turtle and growth hormone cases, that affected many other interests.

WTO Director-General Mike Moore (a former prime minister of New Zealand and not to be confused with anti-establishment American film director Michael Moore, a WTO critic) and other officials insisted that the organization followed democratic principles, arguing that most of its members were democracies and that it operated by consensus. However, even Moore and other WTO supporters admitted that there was some merit to criticisms that the WTO was a "secretive, closed bureaucracy" (Postman, "Everyone has ..."), and suggested that dispute resolution proceedings, in particular, could be opened to more participation.

Given activists' many complaints about the WTO, its Seattle meeting was not the first to draw massive protests. Eighteen months earlier, at the WTO's second ministerial conference in Geneva, Switzerland, thousands of protestors demonstrated against the agency and its policies amid scenes of property destruction, tear gas, and police-protestor confrontations that prefigured some of what would occur in Seattle.

Globalization and Its Discontents

Moreover, while the WTO itself was fairly new, many opponents, especially small farmers, indigenous leaders, and others in developing countries, saw it as just part of a larger process threatening their livelihoods and ways of life. Since the 1980s there had been a rising tide of protests against the World Bank and IMF, whose policies and projects were seen as forcing poor countries to cut social services and as funding projects that displaced communities and undermined local agriculture. Venezuelans angered by austerity measures required by the IMF, landless peasants in Brazil, farmers' movements in India opposing dam projects and agricultural policies, and many others engaged in massive demonstrations that at times included violent confrontations with authorities.

Concerns over, and challenges to, globalization intensified as the U.S. and other countries negotiated individual trade agreements. Approval of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) by the U.S., Mexico, and Canada aroused controversy in all three countries. In Mexico, the Zapatista National Liberation Movement staged its dramatic uprising in the Mayan communities of Chiapas on January 1, 1994, the date that NAFTA took effect. The Zapatistas inspired activists elsewhere, and Zapatista signs, slogans, and red bandannas were frequently spotted during the Seattle protests.

In the U.S. and Canada, unions bitterly denounced NAFTA for accelerating the flow of jobs to low-wage, non-union factories in Mexico. The unsuccessful fight against NAFTA laid the groundwork for much of the organizing that produced the WTO protests. It was in that fight that the labor-environmental alliance against free trade first took hold, as the Sierra Club and other environmental groups raised concerns about lowered environmental protections in Mexico.

Even before Seattle, those opposed to expanding free trade agreements had won some successes. In the U.S., opponents were able to stop Congress from giving the president "fast-track" authority to enter trade agreements that would not be subject to congressional amendment (although fast-track was subsequently approved in 2002). Internationally, free trade skeptics torpedoed talks aimed at producing a Multilateral Agreement on Investment, which they argued would give corporate investors the ability to sue governments if their rules or policies reduced the return on investments. (Corporations had used similar provisions in NAFTA to make multi-million dollar claims against the U.S., Canadian, and Mexican governments.)

All this history and the many issues that it raised came together in Seattle during the WTO's Third Ministerial Conference. Part 2 of this essay describes the build-up to Seattle, the week of the conference, and its aftermath.

To go to Part 2, click "Next Feature"