The fifth essay in the Turning Points series prepared by Walt Crowley and the HistoryLink staff for The Seattle Times focuses on leftwing and labor politics in Seattle and Washington state. The article traces populist and radical agitation from the anti-Chinese riots of 1886 through the 1919 General Strike, Great Depression, World War II, McCarthyist backlash, to the 1999 anti-WTO protests. It was published on February 23, 2001.

"To the 47 states of the Union and the Soviet of Washington!"

This toast was supposedly given in the mid-1930s by "Big Jim" Farley, then head of the Democratic Party and President Franklin Roosevelt's Postmaster General. The line is often quoted to indicate our state's, and particularly Seattle's, historical leftward tilt in politics -- although Farley later denied saying any such thing, and it seems odd that he would belittle Seattle-based liberals who were among FDR's staunchest allies.

Apocryphal or not, the remark contains a kernel of truth. Seattle and Washington do have a rich tradition of radical agitation and experimentation extending from the first labor unions and farmer granges of the 1880s through to the latest anti-WTO protests. For all the romantic elements and genuine acts of courage contained in this saga, however, it is not unblemished by instances of folly, myopia, and even bigotry.

Knights of Labor

The first incidents of "populist" organizing in our state would horrify most modern liberals. In February 1886, mobs led by the Knights of Labor, a loosely structured labor federation, rounded up Seattle's Chinese-born workers and campaigned prevent further immigration. Early labor organizers remained deeply suspicious of "outsiders" of all races and nationalities, largely because of employers who recruited desperate immigrants and low-paid African Americans to break strikes or replace union members.

Labor's nativism and racism (not to mention sexism) began to soften at the turn of the century thanks to a different import: notions of socialist utopia and working class unity, often introduced by European immigrants steeped in the more sophisticated economic politics of their homelands. These newcomers helped to fuel a dramatic surge in local unionism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, despite fierce business opposition and unfriendly authorities. These successes were honored in 1913 by the American Federation of Labor's choice of Seattle for its national convention.

Building Coalitions

In greater Seattle and across the state, many unions made common cause with farmer granges and middle class reformers. Between 1895 and 1915, they provided electoral majorities to elect populists and progressives such as Governor John Rogers, and to win a staggering array of reforms including women's suffrage, rights of initiative and referendum, the regulation of railroads, public ownership of utilities and ports, pensions for the aged, prohibition of alcohol, and universal access to public education.

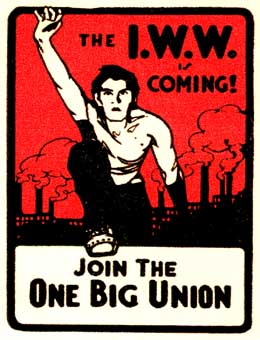

But some on the left wanted nothing less than a revolution to overthrow capitalism and its political machinery. Best known among labor's radicals were members of the Industrial Workers of the World, who organized the lowest and most exploited levels of the work force -- notably Pacific Northwest loggers -- in their quest for "one big union." While the "Wobblies" were not averse to sabotage or violence, they were more often the victims of police, Pinkerton agents, and vigilantes in such famous "massacres" as Everett in 1916 and Centralia in 1919.

General Strike

IWW views and tactics were also attacked within organized labor. More pragmatic and conservative leaders feared that such radicalism would alienate public support and trigger harsh crackdowns, particularly when the United States entered World War I.

War time restrictions and public anxieties sparked by the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 created perilous conditions for labor organizers, but they also emboldened the movement's left wing. Amid a bitter Seattle waterfront strike in early 1919 (and while many local union leaders were out of town), socialist School Board Member Anna Louise Strong rallied labor to call the nation's first general strike.

The wheels stopped on February 6 as workers shut down all but vital services throughout Seattle. In a fiery editorial in the daily Seattle Union Record, Strong declared (hopefully) that "no one knows where" the strike might lead. Seattle Mayor Ole Hanson and local business also thought it was headed straight to Soviet-style communism, but the strike unraveled in a few days for lack of clear goals or public consensus.

The general strike had lingering effects, mostly negative for labor and social reformers. It was invoked to justify government and employer crackdowns on organizers and dissidents, while many unions purged their ranks of more radical (and progressive) leaders.

Getting Reorganized

The movement did not fully revive until the Great Depression. Seattle was again the scene of nationally significant battles such as the waterfront strike of 1934 and the Seattle P-I strike of 1936. A reinvigorated left formed a popular front as the Washington Commonwealth Federation and helped to elect a new generation of reformers, including future Governor Al Rosellini and U.S. Senator Warren G. Magnuson. The New Deal and the Wagner Act, which legalized union organizing, secured permanent gains for labor and its allies, gains which were cemented by the home front needs of World War II.

The post-war recession and rising anti-Communist rhetoric eroded this foundation and again isolated labor's left wing. Conservative unionists such as Seattle-based Teamster boss Dave Beck filled the leadership vacuum (and sometimes drained union coffers) while social radicals were investigated, jailed, or deported. Old habits of racism and sexism also resurfaced as more traditional trades and crafts unions resisted inclusion of minorities and women mobilized by the war.

New World Disorder?

While progressives ultimately regained leadership of most of labor by the 1980s, they faced new threats from automation, overseas competition, and a shrinking manufacturing sector. But labor was not ready to surrender.

As it did a century ago and again in the 1930s, labor is again reaching out for allies, this time in coalitions with environmentalists and the anti-corporate left to resist "globalization." The faceless diplomats and managers of the World Trade Organization have provided an ideal common enemy, and the collapse of the Soviet Union has taken the sting out of accusations of leftist sympathies.

Thanks to the protests of 1999, Seattle has become THE international shorthand for opposition to the WTO and the "new world order." So perhaps today someone in the new Bush Administration is raising a glass in an ironic salute to the "49 states of the Union... and the Soviet of Washington."