A visionary designer, artist, inventor, teacher, builder, lecturer, and businessman -- Seattle's Gideon Kramer was a true renaissance man. Long fascinated by the relationship between materials, technology, design, and function -- and given to flights of insightful socio-cultural and philosophical musings -- Kramer is recognized as one of the greatest industrial designers of our age. A graduate of the renowned engineering program at Chicago's Institute of Design, his achievements were myriad. Kramer devised the first truly ergonomic chair in 1946; began conceiving radically new truck designs in the early-1950s; started teaching Industrial Design at the University of Washington in 1957 and architecture workshops at the University of Oregon in 1960. In 1966 the American Institute of Architects (AIA) honored his "outstanding achievement in fine arts, allied professions, [and] craftsmanship in the industrial arts" by bestowing on him their coveted Industrial Arts Medal. Kramer penned essays for the AIA Journal, The Argus, The Arts, the World Institute Journal of the United Nations, and other industrial arts and design publications. A peer and friend to other Northwest architecture luminaries -- including Ibsen Nelsen (1919-2001) and Fred Bassetti (1917-2013), Kramer also contributed to the look of modern Seattle by designing some of the Aquarium's exhibits and preparing a guideline for exhibit development by the Museum of Flight. He also designed futuristic new offices for U.S. Plywood in Seattle and visually stunning cast-aluminum doors for the Scottish Rites Temple. In 1997 Kramer -- who played harmonica for fun and raised a large family along the way -- was again honored by the AIA who touted him as "the Northwest's closest kin to Buckminster Fuller." Gideon Kramer died on March 5, 2012.

Beginnings

Gideon Kramer was born on March 27, 1917, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to Edward and Brygida (Primula) Kramer. Along with his older sister, Hildagaard, the family moved to Czechoslovakia, where they lived in the mountain town of Dolny Kubin -- the historical capital of the Orava region in northern Slovakia. When he was age 13, the Kramers returned to Milwaukee and Gideon -- after running away from home at age 16 -- eventually received an excellent education by attending the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), the Akron Institute, and the Institute of Design (founded in founded in 1937 by Bauhaus teacher, László Moholy-Nagy), at Chicago's Illinois Institute of Technology.

That same year, Kramer met a fellow student, Ruth McLellan (1918-2009) and around 1939 they decided to go and homestead some land up in Alaska. En route they arrived in Seattle and ended up staying. They married in September 1940. Two years later the young couple had their first child, Edward, who was followed by Lawrence (1944), Brygida (1946), Guy (1948), Lydia (1950), Rebecca (1952), and Milo (1954).

In 1947, the couple started Kramer Candles, manufacturing candles that were sold throughout the United States at stores such as Nieman Marcus in Dallas and Bergdorf Goodman and Macy's in New York. Kramer described the business as "our first venture to make staying in the Northwest possible" (Gideon Kramer email).

A Diverse Career

Over the years Kramer was employed in a wide range of jobs including at a brass foundry, a furniture factory, an aircraft plant, a hydrofoil ferry project, and as a high school art teacher. In each role, he faced new challenges with a keen mind and broad skill set.

"In the course of my work," Kramer once wrote, "I have come to believe that the guiding principles and strategy inherent in the creative process apply to all that is conceived ... be it a chair ... a truck ... a city ... a great meal, or ... making love. With this as my premise I had no inhibitions to cross professionally imposed boundaries, into territory in which I had no standing ... in fact my ignorance became my strength ... . I brought an inquisitive innocence to solving problems for which, in time, I was sought out" (Kramer, 1999).

Streamlined Trucking

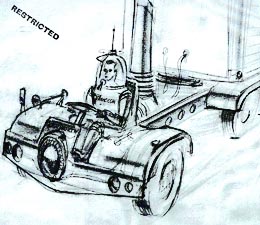

One area in which Kramer had a definite impact was the trucking industry. From 1951 through 1961 Kramer worked as a design consultant for local custom truck builders -- the Kenworth Motor Truck Corporation -- and its parent firm, the West Seattle-based logging truck and railroad car manufacturer, Pacific Car and Foundry Company.

Among Kramer's numerous forward-thinking contributions were patented designs for improved truck components like a new "Bulk-Head Door," which was (according to the 1957 patent application) a "lightweight door structure of unusually rugged" and "novel construction." In addition he designed radically new vehicles such as 1952's "Engine-Beside-Cab Truck" -- whose "lighter weight allowed an additional half ton of cargo. In addition, the new truck provided driver visibility far greater than any other truck on the road" -- and 1954's related, "Cab-Beside-Engine Vehicle" (Kenworth.com).

The Future is Here

Kramer's forward-thinking approach to design was amply displayed in one sketch he made in 1952 of an open-cab semi being driven by a space-suited truckin' man who looks like he'd be comfortable steering a rocket. When that drawing was included in the Fast Forward exhibit at the Tacoma Art Museum in 2000, it prompted one writer to insightfully enthuse that:

"The juxtaposition of art, craft, and technology at the heart of good design is best illustrated by ...Gideon Kramer ... A key narrative in this exhibit is streamlining — an approach almost synonymous with 20th-century design, and one that emerges here as a specifically Northwestern attribute. Canoes, kayaks, bike helmets and bikes, semi trucks, fishing lures, and of course airplanes are all designed or built in our region, and all benefit from moving through air or water with a minimum of resistance. ...The show fulfills its mission: It's a rare, regional-focus show that doesn't seem like mere pandering, whose regional pride seems earned. The future did happen here, and still does" (Ericksen).

ION Chair's Low-Tech Beginnings

Kramer's probable greatest claim to fame was his famous and award-winning ION chair. An icon of mid-century modern furniture design, the ultra-ergonomic chair was a result of his philosophic approach to design. As Kramer told The Seattle Times in 1966, the design came about because he simply viewed the act of sitting as a "dynamic rather than static condition."

The classic chair's origins trace back to 1946 when Kramer helped design an elementary school building and then -- after being charged with specifying furniture to be included -- "I became aware of the requirements as well as deficiencies of seating and decided to see if I could do better," and "the chair took its form from the process which it was intended to support." His first examples "were fabricated out of Vulcanized Fiber, with the simplest of tooling. Soaked in our bathtub, formed on a wood fixture, baked over the living room stove, hung on a wash line to be sprayed with a resin finish," it was initially "a low tech family enterprise" (Kramer, 1999).

Space-Age Seating

By 1947 Kramer's remarkable ION chairs began to gain serious attention. New York's Museum of Modern Art included one in its Fourteen Americans exhibit and also acquired some for their children's section. Years passed and Kramer got involved in many other projects, but when planning began for Seattle's Century 21 World's Fair of 1962, he was ready with an improved version -- one whose sleek and minimalist lines were in perfect sync with the futuristic zeitgeist of that period. Anyone who visited the fair's Space Needle Restaurant would likely have been tickled to have a seat in the ION units that looked and felt like something designed for NASA space travel.

Kramer's use of new shapes and advanced materials -- a smooth molded fiberglass shell set upon a chromed metal base -- was at once purposeful, impressive, and incredibly complex. "The engineering concept of this chair," he wrote, "was so unique that it formed the basis for a mechanical patent" (Kramer, 1999). One patent application revealed the technological challenges behind such a chair, stating that it was an "L-shaped, molded plastic shell comprising a seat portion and a back portion, both joined by an integral concavoconvex nonflanged waist portion [which] is provided with stiffening structure medial of the waist portion" (Molded Chair Patent 3583759).

A Timeless Design

Vastly more comfortable than described on paper, the ION chair met with such a positive critical response -- Interiors magazine described it as "spine-pampering" in a feature article and the Akron Museum included one in their Why is an Object exhibit – that Kramer founded the ION Corporation to manufacture and market them. Then in 1965, rights to produce the chairs were sold to the American Desk Corporation in Texas, and design configurations evolved. There would be an armless model, a lounge-chair model, a swiveling dual-seat model, and even a deluxe "Directors" model which was commissioned for Seafirst Bank bigwigs -- hence a cushy padded seat and an articulated base-stand that allows for full 360-degree rotational mobility.

Ongoing admiration for the ION is based both on practicality -- the chairs are surprisingly comfortable -- as well as appreciation for fine design, and too, just a bit of nostalgia for the innocent early days of the Space Age. Strong demand for ION chairs remains and collectors (including the Northwest's famed glass artist, Dale Chihuly) eagerly sought them out. Top purchasers of ION chairs included Wall Street brokerage houses and various universities and they remained in production for three decades.

ION as Icon

ION chairs have been sold at Christie's auction house, and were exhibited from the permanent collections of both the Brooklyn Museum in New York, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and Denver's Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art. Alas, one of the world's finest collections of ION chairs -- more than 1,000 of them -- was destroyed when the World Trade Center was destroyed on September 11, 2001.

Two years later, the Greater Seattle Chamber of Commerce announced the opening of the city's first full-service destination concierge facility on July 21, 2003. Located on the ground floor of the Washington State Convention & Trade Center, this Citywide Concierge Center boasted a physicality that offered a nod to the "futuristic aesthetic of Seattle's 1962 World's Fair" and its Century 21: World of Tomorrow theme -- including vintage ION chairs.

The Universe Becoming

As the decades passed, Kramer explored many additional creative realms. He designed his own home (2401 SW 172nd) that optimized the lot's sweeping views of Puget Sound and a very cool waterfront cabin for a client on Puget Sound's Crescent Beach. He also invented a state-of-the art slide projector device (the Voyager Presentation System as produced by the Pioneer Square-based Source Technologies Corp.).

In 1966, Kramer was chosen to represent the United States at the first International Symposium on Applied Art, in Barcelona Spain. From 1970 to 1973, he worked for the city of Seattle on Project 27+, establishing guidelines for the beautification of its streets and designs for the city's furnishings. Always exploring new ideas, Kramer showed mixed-media work, "Thoughts on 'The Universe Becoming,'" in a show that opened at the Kent Arts Commission Gallery (220 4th Avenue S) in September 2002.

On August 31, 2009 -- after nearly 69 years of marriage and six decades of raising a family -- Ruth Kramer passed away in the loving presence of her husband and all seven of their children, also leaving behind a dozen grandchildren and 18 great grandchildren. Sadly, in December 2010 the Kramers' Burien home, which they called "h OM e Base" and where they had lived for over 50 years, was completely destroyed in a landslide. For a time before he died, Kramer lived in Seattle and wrote a regular column for the Mukilteo Beacon. He died on March 5, 2012.