In early January, 1812, Pacific Fur Company partners Donald Mackenzie (1783-1851) and Robert McClellan (1770-1815) descend the Snake River to the Columbia in present-day Washington state. Mackenzie and McClellan are among the leaders of a large overland expedition dispatched by fur baron John Jacob Astor (1763-1848) of New York. The overland party intends to rendezvous at the mouth of the Columbia River with other company members traveling by ship. The Astorians, as they are known, plan to extend Astor's trading network throughout the Northwest.

The overland party had departed St. Louis over a year earlier, commanded by Wilson Price Hunt (1783-1842), a St. Louis merchant with an interest in the West. The 60 men, one woman, and two children who made up the expedition ascended the Missouri, then switched to horses to cross the Continental Divide at Union Pass and descend to the Green River in present-day Wyoming. After proceeding north to the Snake River in present-day Idaho, the overlanders built canoes and put into the river which they intended to follow to the Columbia and thence to the coast.

Tormenting Privations

But after losing two canoes, one man, and most of their provisions in the wild rapids of the Snake, the four company partners who shared responsibility for the expedition decided to split into smaller groups and fan out in different directions in hopes of finding either a passable route or Indians who would trade them horses on which to continue their journey. On November 2, Donald Mackenzie, a Canadian who had worked for the North West Company before joining Astor's enterprise, set off on foot along the north bank of the Snake with former Missouri trader Robert McClellan, a clerk, and eight "hands." Mackenzie, experienced in wilderness travel, entreated his men to "take courage; let us persevere and push on ahead, and all will end well," but in reality such an outcome was far from certain.

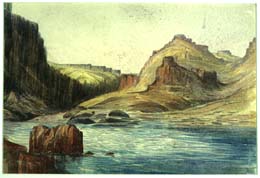

With no accurate maps or experienced guides to rely upon, the 11 men were "under the strong impression that a few days would bring them to the Columbia, but they were miserably disappointed" (Cox, 89). They soon exhausted their scant provisions, then were unable to find any food at all for many days, until "in order to appease their hunger they ate beaver skins roasted over the fire. They even ate their boots" (Franchere, 109). There was seldom any fresh water to be found on the arid plains that bordered the river, and "the cliffs being so steep that they could not go down to quench their tormenting thirst, several were reduced to drinking their urine" (Franchere, 109).

"From the tormenting privations which they experienced in following the course of this stream, they called it the Mad River" (Cox, 90), and when its course bent eastward, Mackenzie's men abandoned its banks and headed northwest. One of the group later recounted that "at this time some of them were so reduced that M'Kenzie himself had to carry on his own back two of his men's blankets, being a strong and robust man, and long accustomed to the hardships and hard fare of the north. He alone, of all the party, stood the trial well" (Ross, 185).

Reaching Fort Astoria

Some days later, in the southeastern portion of present-day Washington state, they came upon a large river flowing west and soon met a group of friendly Indians (probably Nez Perce) who agreed to sell several horses. Among the tribe they noticed a young white man "in a state of mental derangement" (Cox, 91). During lucid intervals, he informed the newcomers that he was Archibald Pelton, a native of Connecticut, and that he had come west with Andrew Henry, an American trader who had built a small trading post on Henry's Fork of the Snake (in present-day southern Idaho). Three years earlier, Pelton alone had survived an attack on the post by a hostile tribe, and he had been wandering about the countryside in despair when he chanced to meet the friendly band who had cared for him ever since.

After slaughtering one of their newly acquired horses for food, Mackenzie and his party gratefully mounted the remaining animals and rode west, with Archibald Pelton in tow. When the river they were following emptied into an even larger stream, the overlanders realized that they had finally reached the Columbia (at present-day Tri-Cities). From their knowledge of Lewis and Clark's route, they deduced that they had been riding along the watercourse then known as Lewis's River, and today as the Snake. Only later would they realize they had actually reconnected with the final stretch of the watercourse they had earlier abandoned, which they had named the Mad River (today's Snake River Canyon).

At the junction of Lewis's River (the Snake) with the Columbia (at present-day Tri-Cities), another amicable band of Indians agreed to trade two canoes for the white men's horses. Around 5 p.m. on January 18, 1812, workers at Fort Astoria "were agreeably surprised by the arrival of Messrs. Donald McKenzie, Robert McLellan & John Reed (clerk) with 8 hands in two canoes" (Jones, 68). Gabriel Franchere (1786–1863) noted that the men were "safe and sound but in a pathetic state, with their clothes in rags" (Franchere, 110). Another witness remarked that "their concave cheeks, protuberant bones, and tattered garments strongly indicated the dreadful extent of their privations; but their health appeared uninjured, and their gastronomic powers unimpaired" (Cox, 92-93).