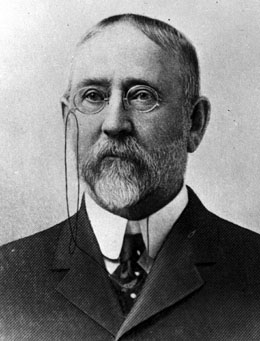

On August 17, 1888, Roslyn miners strike for an eight-hour day, and the Northern Pacific Coal Company brings in trainloads of Black miners as strikebreakers. To protect the strikebreakers and to intimidate miners, the company hires 40 armed guards. This precipitates a legal and constitutional crisis, as Territorial Governor Eugene Semple (1840-1908) fears that this armed body constitutes a virtual private militia. He calls it "an outrage" and orders the guards dispersed or arrested. The strike will be settled, and the guards disbanded. Yet many of the Black miners and their families will remain in Roslyn for decades.

Violence Averted

Roslyn was only two years old when the Knights of Labor called for the strike. These coalminers wanted an eight-hour day instead of the 10 or 11 hour days they commonly worked. The situation became tense and violence erupted. The company refused to negotiate and instead recruited about 50 Black miners from the Midwest and the East, who arrived by train, accompanied by nearly 40 armed guards. Guns bristled from the windows of the train.

The company feared violence against the strikebreakers, but none ensued. When word reached Governor Semple that the guards were behaving like a paramilitary organization and bullying the residents of Roslyn -- and that they were calling themselves "U.S. marshals" -- he realized that this was a challenge to the authority of Washington Territory. He ordered the county's sheriff to disperse or arrest these "detectives." The sheriff found them entrenched at mine No. 3, but they eventually withdrew, defusing the crisis.

Governor Semple Speaks Out

Semple himself came to Roslyn to investigate on August 29. His report was a scathing condemnation of the company's practices. He said the company had operated on three suppositions, all erroneous: That the Black miners would give offense to the white miners; that the whites would attack them; and that the local police would be unable to stop them. He said he found the people of Roslyn to be "law-abiding and intelligent." Bringing in these "detectives" was "unjustifiable" and "may be properly characterized as an outrage." Semple called such schemes "the instruments of the rich and strong for the oppression of the poor and weak" and "a serious menace to our free institutions."

Semple succeeded in defusing this crisis, but to the disappointment of the striking miners, he didn't intervene in the labor dispute. After several more work disruptions, the strikers yielded without winning many concessions. Many strikers were not hired back.

The Black miners stayed on and over time tensions eased. During the next two years, many more Black miners arrived, bringing the total to 300. Many brought their families. By 1900, Roslyn's population was 22 percent African American, one of the highest in the state.