This is the second essay in a special series of essays commissioned by The Seattle Times to examine crucial turning points in the history of Seattle and King County. This segment examines the interplay of "Roads, Rails, and Regional Planning" in shaping urban and suburban development since the 1880s. It was written by Walt Crowley and the HistoryLink Staff and first published on October 24, 2000; this version incorporates minor corrections and clarifications.

Roads, Rails, and Regional Planning

Early on the morning of April 13, 1941, Seattle's last streetcar ended its run and rolled into the Fremont car barn. Ever since, people have dreamed of reviving some form of rail transit to serve the city and the region.

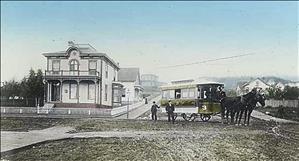

Seattle's street railways had developed haphazardly beginning in 1884. The first lines were built chiefly by real estate developers interested in attracting homebuyers to "suburbs" such as Ballard, Columbia City, and West Seattle. Control of the city's 22 private street railways was consolidated in 1900 by the national utility cartel of Stone & Webster (granddaddy of Puget Power), which also built electric interurban lines from Seattle to Tacoma and Everett.

Before the automobile and widespread road construction, these railways offered fast and efficient links among neighborhoods and nearby cities. They also defined a land use pattern of broad avenues, dense residential areas, compact business districts, and attractive parks -- the basic hallmarks of today's "urban villages."

By World War I, the private system faced mounting financial problems and commuter complaints. The city bought the streetcar lines in 1918 for an inflated price that hobbled its ability to expand or modernize. Seattle's streetcars became pawns in a titanic struggle between private power companies and public utilities, and between car manufacturers and mass transit systems.

On the eve of World War II, the city reluctantly scrapped the system in favor of buses and electric "trackless trolleys." Had the system survived just a few months longer, the war effort might have saved it. As it was, Seattle's street railways were gone but not forgotten.

Between 1940 and 1950, King County's suburban population doubled to a quarter million (and would surpass Seattle's by 1970). The trend alarmed the Municipal League and a young lawyer named James R. Ellis, who feared that unplanned growth would create future environmental and traffic problems. They championed a new County Charter to establish, among other things, a regional transit system. The plan was denounced as "communistic" and rejected by nearly two to one in 1952.

In 1956, President Eisenhower signed the National Defense Highways Act. This unleashed federal funding for the interstate highway system, with the stated purpose of moving troops during a nuclear war, not just goods and civilians. It also established the most heavily subsidized transportation system in history -- far surpassing all public funding for rail before or since.

As the State Highway Commission began planning the Interstate-5 Freeway, local officials begged it to include a right of way for future rail transit. The state replied that the cost, an estimated $16 million, was "too high." Rail advocates responded with a proposal for the Municipality of Metropolitan Seattle that included authority for regional planning and transit. Voters said no in March 1958, but approved a more limited "Metro" sewage utility the following September. Metro tried for transit authority again in 1962, banking on excitement over the World's Fair and new Monorail. The Auto Club countered with a well-financed campaign (bankrolled, some suspect, by car companies and contractors), and the election coincided with the opening of I-5. For a brief, shining moment, traffic congestion was not a worry, and voters cruised by.

Regional transit plans suffered a new blow in 1966 when the state-funded Puget Sound Regional Transportation Study flatly rejected any role for rail. Instead, it outlined a web of new highways, including a bridge from Seattle to the Kitsap Peninsula via Vashon Island. More roads were welcomed by many, but some saw the plan as a virtual prescription for sprawl.

Jim Ellis and other activists then joined forces to plan Forward Thrust, a grab bag of regional improvements including parks, housing, roads, and a domed stadium (which we just demolished). Seven of 12 propositions passed in 1968, but not rail. Transit failed again in 1970, and a billion dollars of federal aid reserved for Seattle's system went to Atlanta instead.

If local voters were wary of rail, they were also not overly fond of new highways. Environmentalists joined with neighborhood activists to stymie plans for a colossal I-90, and Seattle voters erased the proposed R. H. Thomson Expressway and Bay Freeway from the map. Eastsiders were also disappointed by 405 and the Evergreen Point Floating Bridge, which quickly filled with cars.

With Seattle Transit and suburban bus companies facing bankruptcy, Metro took one more run at the problem. To avoid controversy and the high hurdle of a bond issue, Metro asked for a sales tax increase to fund an all-bus system. Voters finally said yes to Metro Transit in September 1972.

The itch to build a rail system never quite faded, however, for the simple reason that it offered the best way to move large numbers of peak-hour commuters, especially through Seattle's narrow, wasp-waisted downtown. Voters also began to warm to the idea, and a two-thirds majority endorsed a 1988 advisory ballot to "accelerate" planning for rail service.

By then, Metro was digging the downtown transit tunnel. Despite predictions of physical and fiscal disaster, Metro completed the tunnel on time in 1990 and within 10 percent of its original budget.

That same year, a revolution took place in Olympia with passage of the Growth Management Act and enabling legislation for a Central Puget Sound Regional Transit Authority (RTA). Just when regionalists seemed on the verge of realizing the dream of coordinated regional planning and rail transit, Metro's federated structure was found to be unconstitutional. The agency was absorbed by King County government in 1993.

Two years later, voters rejected RTA's first plan for a $6.7 billion, three-county system combining heavy commuter rail, light rail, express buses, and expanded HOV lanes. A leaner $3.9 million "Sound Transit" plan passed on November 5, 1996.

This vote was hardly the last word. Impatient Seattle voters endorsed an expanded Monorail system the next year (they get the chance to fund it this November). Meanwhile, Sound Transit finds itself besieged by a new -- yet historically quite familiar -- army of critics who think it is too big or too small, too radical or too conservative, too soon or too late, and digging too many tunnels or too few.

Only time will tell if a modern descendent of Seattle's last streetcar ever sees the light of day.