The eighth essay in HistoryLink's series of Turning Point essays for the The Seattle Times recaps the history of the YMCA of Greater Seattle, and parallel developments in Seattle's religious, social, economic, and educational development. The article, written by Cassandra Tate, is condensed from a longer narrative prepared by HistoryLink for the YMCA's 125th anniversary. The essay was published in the Times on May 11, 2001.

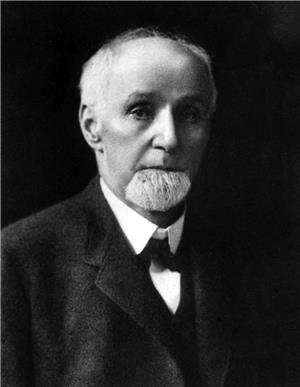

On August 7, 1876, pioneer banker Dexter Horton and 14 other prominent citizens established the Young Men's Christian Organization of Seattle. Their goal was to save young men from the free-flowing whiskey, the women of dubious reputation, and the other temptations of a frontier town -- to replace evil with good, immorality with Christian values, idleness with self-improvement.

Despite its declared emphasis on youth, the YMCA's appearance in Seattle actually signified the town's maturity. In the quarter century since arrival of the first white settlers, the population had grown to nearly 3,000 souls. The city's emerging middle class recognized that Seattle had to outgrow its rough and tumble ways and begin thinking and acting like a civilized community if it was to realize its potential as a modern city.

Originally, the Seattle YMCA interpreted its mission in strictly religious terms, offering Bible study and prayer meetings to young men at a time when there were few churches to fulfill that function. It soon took on broader roles, promoting the unity of mind, body, and spirit, and widening its focus to include the boys who would become young men, and, eventually, the families from which they grew.

Spiritual or Physical -- or Both?

A scant two years after it was born, the Seattle YMCA was operating a library, sponsoring lectures and socials, and maintaining an informal employment agency, in addition to conducting twice-weekly Bible classes and prayer meetings. Members could look for hometown news in dozens of periodicals from around the country, including several published in Swedish and German, or relax with games such as chess, checkers, and crokinole -- a board game, similar to tiddlywinks, that was popular at the time. A boarding house directory was available for young men seeking respectable lodgings.

By the end of its first decade, the YMCA was home to Seattle’s first gymnasium, equipped with “the latest approved apparatus,” and staffed by a physician to recommend personalized exercise regimens (not unlike a personal trainer today). This was followed in short order by a bathing beach with a bathhouse and diving platform, on Elliott Bay behind the Y’s rented quarters on what is today 1st Avenue, and an athletic field, on Cedar Street.

But Dexter Horton thought the organization had lost its way. When asked to contribute to a fund for a building with a larger gym -- and the city's first swimming pool -- in 1888, he flatly refused. “No sir, not one cent,” he said. “The Association has departed from the purpose for which it was organized, the spiritual uplift of young men, and now you propose to make it a gymnasium and a swimming pool. If the boys need exercise, let them saw wood, and if they want to swim, let them go into the Bay.”

Fortunately, Horton represented a minority point of view. YMCA President A.S. Burwell pointed out in 1890 that more and more young men were working in sedentary jobs and had no opportunity for physical exertion through their employment. Many were also working fewer hours, with more time for leisure activities. Better that they spend that time in “profitable exercise,” he argued, than in the “Devil’s traps” that were “open day and night, to ruin them.”

It was troublesome, however, that an average of 350 men were using the gymnasium every month while fewer than a dozen were attending the weekly Bible classes. The classes were moved from Wednesday to Saturday evenings in an effort to boost attendance, to little effect.

Practical Education

The waning interest in the YMCA’s religious activities was balanced by the growing popularity of its educational programs, which evolved from a “Winter Course of Practical Talk Lectures” in 1886 to a few adult education classes in 1888 to a full-fledged college preparatory and vocational school by 1899.

Seattle served as a magnet for thousands of young men from small farming communities and foreign countries. Many of the newcomers were poorly educated, leaving them “handicapped in the race of life in our city,” as one report noted in 1893. With its ventures into education, the YMCA committed itself to helping such men (and, much later, women) acquire the skills needed to succeed in a rapidly changing economy.

The vocational school -- initially called the YMCA Night School and later the Association Institute -- was the first and for many years the most successful of its kind in Seattle. The primary focus was on what Harold A. Woodcock, longtime educational director of the Seattle YMCA, called “practical education -- the sort that equips the man for efficient work in some special department,” such as bookkeeping or drafting.

Follow the Bouncing Ball

Finding the space to accommodate this widening array of programs was a constant challenge for the YMCA. The organization moved eleven times between 1876 and 1890, going from one rented building to another, usually occupying second-floor rooms above a factory or store, spaces that were often inaccessible and hard for a stranger to locate. It March 1890, it settled into a building of its own -- the first to be owned by a YMCA in the Northwest -- on First Avenue between Union and Pike.

The Y’s new home included a large auditorium, modern gym, game and reading rooms, classrooms, and Seattle's first indoor "natatorium" where, in the tradition of the time, men and boys swam unashamed and unencumbered by bathing trunks. This practice ended when women were admitted to YMCA pools.

A few months after moving into the new building, the board of directors revised the Articles of Incorporation that Horton and the other founders had adopted in 1876. The new statement of purpose reflected the organization’s expanded role: “The object of the corporation shall be the improvement of the Spiritual, Mental, Social, & Physical condition of the young men of Seattle..." through a wide array of services and programs.

In 1891, the YMCA hired its first full-time athletic director, Thomas S. Lippy. He launched the organization's first camp programs and introduced Seattle to a new game called "basket ball." When gold was discovered in the Yukon in 1897, Lippy joined thousands of prospectors on the rush to the Klondike. Unlike most, he returned a rich man, and he later donated part of his fortune to help fund the YMCA's present Central Branch at Fourth and Marion, completed in 1930.

Over the ensuing decades, the YMCA has been a regional leader for childcare, adult education, and a host of social programs. Today, its downtown and suburban branches serve more than 154,000 men, women and children each year. Dexter Horton would not recognize and nor probably approve of the modern YMCA of Greater Seattle, but the organization has succeeded largely because it has changed with the times, adapting policies and programs to meet the shifting needs of the past 125 years.