Vivian McPeak, a resident of Seattle's University District, is the founder of Seattle Peace Heathens, executive director of Seattle Hempfest, and a local peace and social-justice activist. This is a transcript of an oral history that McPeak gave when interviewed by Dawnee Dodson for the University District Museum Without Walls in March 2009. The Museum Without Walls, a project of the University District Arts & Heritage Committee, draws together the history and life of the University District through a variety of formats, including temporary exhibitions, community events, and oral histories.

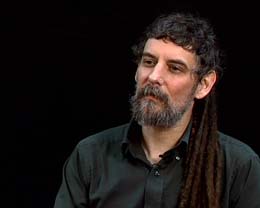

Vivian McPeak

My name is Vivian McPeak. I'm the executive director of Seattle Hempfest, and I have been a peace and social-justice activist in the University District of Seattle for a little over 20 years. I grew up in California, but I went to high school at Ballard High in 1974 for -- I think it was my sophomore year. And I really fell in love with Seattle and the culture here, and I returned in 1986 and I've been here ever since.

I was raised partially by my grandparents, and my grandfather was senior national representative for the largest federal government labor union, the American Federation of Government Employees, AFL-CIO. And when I was 10 years old, my grandfather introduced me to Hubert Humphrey, the vice president of the United States, a couple of times, and the president of the United Nations, and several senators. I was a -- at 10 years old I was an honorary member of several locals, and I had a pair of alligator shoes and a white dinner jacket and a double-breasted Edwardian suit, and I was basically really a little -- I was basically a small, what's the word -- "establishment" person, you know? So by the time I was 11, I kind of rejected the establishment, and started rebelling. But those kinds of seeds of political awareness were really ingrained in me. Also, we lived right next door to the Ambassador Hotel, and Robert Kennedy was assassinated while we lived there, just less than a block away from where we lived. And that was a big impact on me as well, because we were scheduled to actually go there and meet -- and be a part of that whole thing. I was going to go with my grandparents. And so that early, that kind of politicizing, plus growing up in the sixties -- I was 10 years old in 1968 -- had a huge impact on me. I always wanted to be -- I always wanted to hook in with the spirit of what was going on, and be a part of what I saw as a solution. Or, maybe better, a small piece of positive change.

I was a rock musician through most of the late seventies and the eighties, and a band that I was in in Los Angeles broke up around 1986 and I came back to Seattle basically to work for my dad, because I didn't have any work at that time. And I had been thinking -- a couple of things happened to me in the next year, and I'll try to encapsulate them. There was a gentleman who -- I had a family and a wife and a child and everything, and we separated around this time and I ended up with all of this stuff. I had -- they went back to California, so I had toys and dishes and bedding and all this stuff that was really more than one guy -- single guy -- needed. And about this time I saw an article in the newspaper about a gentleman in Carnation, Washington, who had lost everything. His wife and two of his four children had been burned to death in this mobile-home fire. They were having this new start, they'd just bought this mobile home -- long story. And he -- there was a picture of him in the hospital, and he was all burnt and bandaged up and he had one of his remaining kids on his belly, and I thought, "Wow, I have all this stuff and there's this guy who needs --." They were saying in the newspaper that he was making a fresh start. He'd lost everything he owned, and he had to raise his two kids. And I thought, "What if I hooked up with this guy and I gave him all this stuff that I have?" It seemed like it would be a positive use.

Community Service

So I called the number in the newspaper, and it was a wrong number. And I spent a couple of days and about 20 calls, and I called everybody I could think of, the fire department and the Harborview burn unit, and eventually I tracked down the right number for the woman that was doing this donation drive. And at the time I had a purple rock mullet -- bright purple -- eyeliner, dangly earrings, black leather jacket, black cowboy boot, stretch jeans. I mean, I looked totally like an eighties glam rocker would. And I packed all this stuff, well, actually I got a hold of all my friends and I had everybody donate all they could, and I talked to the local thrift stores and I got stuff donated, you know, until I had all kinds of stuff. And I drove down to Carnation to meet this guy one night, and knocked on the door, and the guy opened the door. And he was a good old boy, he was a logger, and he started crying. And he was just blown away that somebody that looked like me -- and he told me, "I wouldn't have spit on someone who looked like you five minutes ago." And I was the only person that donated anything, because they had the wrong number in the paper, and nobody else went to that effort. So it really profoundly changed me, that experience of -- and they brought me in and gave me cookies and milk, and basically I never would've been in their home, they never would've associated with someone like me. And so I realized at that time that there were a lot of alternative-culture people who would like to -- or would benefit from -- community service, with being involved in community service. And that there really was no vehicle for young music-culture, especially alternative-culture, people to do something like that.

So this really inspired me to start thinking about what an organization would be like that could attract street-level people to do something positive and build self-esteem, give them hopefully some job training, some skills, interacting with other people and communication skills and stuff like that. And basically just a sense of being, of self-worth.

I had really never been to the U District. And my girlfriend of that time brought me to the U District and I was totally blown away by the culture that was here in the eighties, in the late eighties, and there was -- the grunge movement was in full bloom, as I said, and the poles on the Ave were this big (gestures) with posters, with band posters and rock posters. And it looked to me like Telegraph Avenue looked in the sixties. So I realized really quickly that this was the spot, if I'm going to do this thing that I want to do, this is the part of town I want to do it in. I gave notice at my job, and one of the guys that was dishwashing for me says -- I was telling the guys I worked with my crazy scheme that I had. He says, "I live in this little shack on 45th, not far from the Ave, and I'm looking for a roommate." So I ended up moving in with him, in this dingy little "heroin shack," they called it. And not long after that I stumbled across this place called the Last Exit on Brooklyn. It was the oldest coffeehouse in Seattle, and it was absolutely an institution in the University District. It was an anchor of community in the University District. I lucked out because I got hired there immediately that first time I walked into the place. And it really was a blessing for me because that was my office, that was my operating center. And I was there every day working, and basically everybody who was kinda involved in the "scene" in Seattle -- a lot of overlapping cultural circles at some point blew through the Last Exit on Brooklyn.

So I started this group called the Seattle Peace Heathens Community Action Group, and it started off with just a piece of paper that was our creed, our kind of statement to the world. And I started to get a lot of phone calls and so -- long story short -- we ended up having these meetings, we had potluck meetings that went on for years in Seattle. In fact, they haven't stopped because the Hempfest picked them up, so it's been about 20 years consecutively that we've been having these summer potlucks in the park and stuff. In those days, anyone was welcome, and we would feed anybody who came, showed up, as a community service. And also maybe as a little bit of an attraction to come and hear what we had to say.

Activism

The Bush years were very frustrating for me as an activist. Very -- almost disillusioning for me. The first Persian Gulf War, which, it seems to me, was one tenth of what the invasion of Iraq was, seemed to mobilize just thousands of people. By the time we were down at the Federal Building -- we shut the Federal Building down for seven days. Shut it down! Nobody could come to work for seven days. We had a full occupation of that courtyard of the Federal Building. We built a wooden permanent stage in the courtyard with an awning and everything -- platform stage. We had two 24-hour kitchens going on at the Federal Building compound. We had tents inside the Federal Building compound. I was sleeping in a tent on the Federal Building property, which is outrageous. When we first initially did the Federal Building takeover, the Coalition for Peace in the Middle East showed up with these trucks with these big rolls of orange plastic snow fencing. And we unrolled that snow fencing, and we had three layers thick. People tried to come to work and we'd be holding up three layers thick of snow fencing, saying, "Call in! Call in well, your government's sick!" And we had old ladies and punk rockers and, I mean, nuns, all there and -- "No, you're closed!" I mean, we surrounded the Federal Building with a thousand people and held it for a week. Until the gig was up, obviously. And, ironically, I happened to be the only person from the steering committee at the time who was awake at four in the morning when the police came to negotiate the thing, so I ended up having that responsibility and that honor.

But what I'm leading up to is that when it came time for the second thing, the Iraq War, -- man, it was totally different. First of all, the Federal Building was totally different. I mean, we're talking complete riot gear with M16s and you can't even get on the sidewalk in front of the Federal Building. That was the difference between pre-9/11 activism in Seattle and post–9/11 activism. And so I was really surprised that the reaction that Seattle had with demonstrations and with activism was a lot less than I anticipated. And it seemed like the fear factor from 9/11 was a huge part of that, and from the Bush -- I'll say "administration," but I think another word would be more appropriate. I don't think it even was a presidential administration, in the sense that they were busy running a campaign and an exploitation for corporate profit instead of paying attention to what was wrong with the nation. And if there was ever a time for grassroots, street-level activism, I think it was during the Bush years. Yet, from what I could see, it was more of a lull period, comparatively.

I would encourage anybody who's thinking about getting involved, especially in radical activism, to never get too carried away with what you're doing, and think that your cause trumps other people's sensibilities, privacy, whatever it may be. It's a balance; you've got to strike that balance. Back in 1990, I think it was, we took over the freeway three times to oppose the Persian Gulf War. And I was on CNN as the first person -- I had a flag over my face and I jumped on the thing and I had people calling me from other states -- (in an exaggerated "hippie" accent) "Hey Vivian! I could tell that was you, man! What were you doing?" and that kind of stuff. And I think it was the second one where we sat down on the freeway, shut it down, stopped traffic until the police came and got rid of us. And somebody died in an ambulance. A guy died -- a heart-attack victim. And we'll never know if that guy died because he wasn't able to get to Harborview because we were blocking the streets or not.

But that had a big impact on me. I thought about that for a long time, trying to figure out whether what we did was the right thing or not, you know? And I'll really never really know that. But it's something that really changed me, and it changed the way I looked at my activism, and I realized that that guy's life was important too, obviously, and people on the freeway have -- they're all involved in something that they're doing. And you really have to do a serious cost-benefit analysis and really do some soul-searching when you think about civil-disobedient activism. And you really have to look at what you're doing and make sure that you're not hurting your cause. Images of angry people with their fists in the air, you know, hurling stuff -- to the general public it kind of looks like crazy, fanatical obsessed people who are out of control. And so you really have to think about what your vehicle is for getting your message out, and how you're going to look to those people that are home eating dinner and watching their TV set. And I think a lot of radical activists miss the boat sometimes on their desire to get their feelings out, and their rage, and to oppose something. But also what is their message looking like, and their packaging, and is it getting into the minds and hearts of the people that they're trying to reach out to?

Economic times like this make it really, really hard on activists. There's no money in activism, at least not in the street-level form of it. And so most activists are voluntary peasants. And the less resources there are out there, the less time that you have time to devote to things that aren't going to make you any money. And so it's really up to the more -- at times like this it's really up to the more creative who have nonprofits, and maybe have grant writers, and who can maybe actually generate some money to get them through this hard time. Because it's going to be tough. So I know one thing -- activism is going to take a hit through this economic challenge that we have.