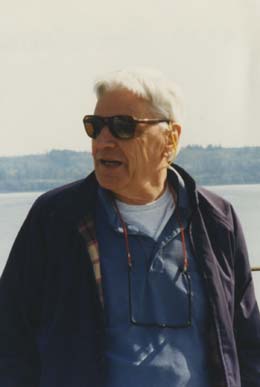

In this People's History, Frank Chesley (1929-2010) recalls his six years working for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer as a TV columnist. From 2003 until his retirement in 2009, Frank was a staff historian at HistoryLink.org.

The Seattle Years

It had been about 14 years since I left Seattle -- 14 itinerant years, out there mustering some proper news bum credentials.

After a year at United Press in Seattle, there was a year in Stockton, California, writing for farm and seaport house organs; six years in San Francisco editing an advertising trade journal and doing some PR for Matson Lines; a couple of years in London, translating English into North American for Reuters; three years in West Germany, copyediting and writing for Stars & Stripes, the newspaper for U.S. forces in Europe; a couple of years back in San Francisco, reporting for the Chronicle and writing for a short-lived feature magazine. Stability apparently wasn’t my destiny.

In 1969, out of work, with a new wife and child, and casting about for ... for anything, I wrote a catch-up letter to an old University of Washington Journalism School classmate, John Voorhees. He had gone directly to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer from school, and had been writing the P-I television column, I thought. No, he had left the P-I a couple of years earlier and was now covering the arts for The Seattle Times. The P-I’s TV job was open.

I flew up, applied, and was hired in October 1969 by managing editor Lou Guzzo, despite my barely superficial knowledge of television or criticism. My wife of a few months, Justine, and I hitched a trailer full of belongings to our Volvo, wedged son Theo into a corner of the back seat and headed north.

It was not the first time that luck, karma, guardian angel, or St. Christopher had saved my ass.

Come to find out, a couple of Voorhees’s successors hadn’t lasted long, and the TV job had become sort of a black hole at the P-I, a situation about which I was fortunately oblivious. On my first day, while being introduced around the city room, I remember Darrell Glover asking, “Well, how long are you going to be around?”

Guzzo had made a name for himself and the P-I around the time I arrived, working with reporters Shelby Scates and Mike Layton in exposing a police gambling payoff system. It led to the indictment of more than 50 police officers and dethroned Charles O. Carroll, King County Prosecuting Attorney and Republican kingpin. It also triggered a profound change in local politics.

Scates remembered Guzzo and Assistant Managing Editor Jack Doughty as “hellaciously good editors and real newsmen.”

Guzzo oversaw a sometimes-outrageous, free-wheeling staff of writers, reporters, and photographers, a mirror of the times, mostly left-leaning, mostly hard-drinking, and more than a few toking regularly. Guzzo himself, however, was curiously conservative. After my hiring, our paths crossed only occasionally, always pleasant.

On March 27, 1972, Guzzo sent the now-famous “Amazon memo” to lifestyle editor Sally Raleigh, expressing his concerns about the proposed Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which had been recently passed by Congress and sent to the states for ratification. He feared that ERA would "promote a new breed of Amazons" and suggested a piece or pieces on the possibly deleterious impact of the ERA.

Big mistake. Raleigh posted what came to be known as “the Amazon memo” on a newsroom bulletin board. Reporter Susan Paynter went on to write a prize-winning 12-part series supporting the ERA.

Raleigh was a third-generation newsie, gravel-voiced, three-martini-lunch kind of editor who, along with assistant lifestyle editor Lettie Gavin, was revolutionizing the old “women’s pages.” In Raleigh’s obituary in the P-I of March 29, 1993, reporter Judi Hunt quoted Paynter as saying,, “A petite personification of the contradictions of those years, she led her troops -- most of us young women in our 20s -- into the little-explored territory of social-issues reporting ... . But she seemed almost as proud of the fact that, after a protracted battle of memos with the male executives, she won the right for women at the P-I to wear pantsuits to work."

Guzzo had spent 20 years at the Times, as an arts reviewer, before moving to the P-I. When he left the P-I, he went on to become a consultant for the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and later the chief adviser for Governor Dixy Lee Ray, a far-right-of-center Democrat, with whom he coauthored two books. He then became a commentator for KIRO-TV, and later launched his webpage, the “Daily Voice of Reason.” He has continued to expound a really conservative point of view.

In 1985, while at KIRO, Guzzo delivered a commentary ripping into punk rock, which had evolved into another antiestablishment genre. One local punk-rock band, The Dehumanizers, incensed at the slur, gained instant notoriety with their song “Kill Lou Guzzo.” The song was released as part of their debut album, titled Kill Lou Guzzo.

But Guzzo also was among those who saved my ass. And when I got into the column, despite its progressive tilt and an occasional outside skirmish, he encouraged me to keep doing what I was doing. So it’s difficult to be too hard on him.

What a time it was -- the late sixties, early seventies. More and more ferment generated by more and more people.

The Troubles were reaching critical mass and once-backwater Seattle was doing more than its share for the antiwar effort. On July 28, 1970, Mayor Wes Uhlman told a U.S. Senate committee that Seattle had the highest number of bombings per capita in the nation -- 90 of them in the 17 months since February 1969. Seattle was up there with New York and Chicago on the violence index.

The University of Washington was the local UC Berkeley, the student hotbed. There were arson fires, bombings, and its ROTC building was a regular target of the antiwar rage. Seattle Police were using plainclothes goon squads to beat up protesters, a tactic refined in the Central District Martin Luther King rioting in 1968. The university quadrupled its police force, the campus became something of an armed camp and Dave Wilma, on the UW force at the time, said the Seattle Police were happy to wash their hands of the whole mess.

Racial tensions were erupting in riots, demonstrations, sit-ins, inside the ghetto and out.

Women, as the P-I’s lifestyle section was ably demonstrating and reporting, were on the march.

Seattle was on the march too, even without the riots. It had grown in those 14 years, inside and out, mutating into one of the country’s “most livable cities.” The 1962 Seattle World’s Fair -- like the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in 1909 -- had kicked Seattle’s presence up a couple of notches. The citizens of King County had voted to clean up polluted Lake Washington and in 1968 passed an $815.2 million package of civic-improvement bond issues called Forward Thrust. Unfortunately, a rapid-transit measure failed again.

The “Blue Law” banning Sunday commerce -- violated openly by thousands of businesses – was voted out in 1966. There were some decent restaurants, and the wine selections had expanded beyond NAWICO Blackberry fortified. Women not only could now drink in bars, but some of the tonier eateries were allowing them to wear pantsuits. Progress was breaking out all over.

Except for the economy. Our arrival also coincided with the Boeing Bust, when the Lazy B cashiered more than half its 80,400-member work force. Seattle’s unemployment rate was the highest of any major American city -- 12 percent -- and two real-estate agents posted that now-famous billboard near Sea-Tac Airport: "Will the last person leaving Seattle -- Turn out the lights." Inflation was further buggering up the economy and an energy crisis was looming.

We, however, had Horatio Algered into at least a decent-paying job and a promising circumstance. The move was eased by old friends from UW days. Gordy Culp and his wife, Joan. And from journalism school days, Voorhees, George and Aldine Lowe, Bill and Nancy Hevly, Dave and Joyce Woods, and Kirk and Peggy Smith, who were back in Seattle after their California tour. I had temporarily crashed with the Smiths when we were all in San Francisco in the mid-fifties.

Culp was now a principal of Culp, Dwyer, Guterson and Grader, which had become one of Seattle’s higher-profile law firms. Culp and I had bunked with other recent UW graduates on a couple of occasions, one of them in a scuzzy, lower Queen Anne apartment aptly known as Gorilla Villa. We had stayed in touch and reunioned in London when I was working for Reuters. Through Culp, we became friends with Bill and Vasiliki Dwyer and other members of the firm.

Culp was establishing himself out of the public eye, becoming a major player in the region’s complicated, politically sensitive power battles. Robert Marritz, a former law partner, said: “There was a need to coordinate conflicting, overlapping interests: public power -- itself diverse -- private utilities, aluminum companies, and the public interest. Culp was the titular head of the power industry legal community, figuring out these problems, trying to get the parties together to get more kilowatts out of the resource.”

In 1964, Culp engineered a landmark treaty with Canada to enhance Columbia River hydroelectric potential. He also helped develop the Pacific Northwest Utilities Conference Committee (PNUCC) into a significant industry forum-cum-lobbying group. When the Washington Public Power Supply System (WPPSS) was en route to a $2.25 billion meltdown -- the largest default in municipal bond history -- Culp was in the middle of it.

Egil “Bud” Krogh, who had been aided by Dwyer after his indictment for the Watergate “Plumbers” business, reflected: “Gordy and Bill were the animating spirit of a law firm that was ... and I don’t want to overstate it, but in a way it was Camelot when the two of them were there. Not only were they super competent and extraordinarily effective lawyers and litigators, but they had a social conscience.”

Dwyer went on to become an outstanding U.S. District Court Judge. He died in 2002 at age 73. Culp retired and died in 2006, at age 80.

An example, maybe, of how small a town Seattle still was: We also connected to the Dwyers through Kirk and Peggy Smith. Kirk and Dwyer were old Queen Anne High School buddies and the Smiths had recently sold their Montlake District home to the Dwyers.

George Lowe also introduced a new strain. George and I had co-edited the UW humor magazine, Columns, back in 1952 and also had stayed in contact. He and his wife, Aldine, had spent a couple of years in the Bay Area in the late 1950s and we bumped with some regularity. But they were Seattle folk and had to go home. George was in the advertising business and was surrounded by a cohort of high-rev ad folks. There was Bill Johnson, a sax-playing-designer-illustrator-aviation photographer, and his artist wife, Nancy; photographer-gourmet Bob Peterson and his wife, Lynne, and writer-musician Paul West.

The group was deeply into good food, beverage, and camaraderie and there were some memorable, afternoon-long lunches at Francois Kissel’s Brasserie Pittsbourg, in a Pioneer Square basement.

Bill Johnson, a Texas boy always ready to tell it like it was, also was a regular at the regional air shows, and all the old flying fantasies were given new life. We were regulars at the regional air shows -- at Paine Field and Abbotsford, B.C. The plane connection provided a few memorable rides over the years, among them an air show routine with the Canadian Snowbirds demonstration team (for whom Bill was the sort of official photographer); and in a Whidbey Island A6 Intruder practicing dogfighting over the Olympics.

Bill led us to Rick Millson, then managing the Paine Field Air Show. Millson had done a couple of tours as a carrier pilot in Vietnam, and a tour with the Blue Angels, before abruptly quitting the Navy. He was working his way back to respectability after being busted at a California airfield with a planeload of Mexican pot. More on Millson later.

Some of Lowe’s sailing-drinking buddies hung out at the Central Tavern, and among its other regulars was Walt Crowley, a onetime radical, alternative journalist, and politico-civic gadfly. Walt and I would reconnect some years later.

The rotten economy worked in our favor as well. Dave and Joyce Wood were living in a mini-mansion on Queen Anne’s Lee Street – cheap at the time and needed for their large brood. Dave was deep in Democratic Party politics, knew a fellow traveler down the hill -- attorney Floyd Smith -- who was trying to sell his house at 1104 8th W, so that he and his wife could move to Anchorage. With the housing market belly up, we got the old three-bedroom house, with a view of Puget Sound and the Olympics, for $20,000. We scraped together a down payment and finally had a real home. It had been a while.

The television beat was another jump-off-a-cliff. Neither Guzzo nor anyone else at the P-I expressed any notions about what a TV column should look like, and I certainly had no idea. There was no template, no expectations, no do’s or don’t’s. I had been a 49ers and Raiders fan in the Bay Area and football was the only programming I had watched with any regularity. I had written a few stories about show biz personalities for a short-lived magazine and that was it.

They ran pretty much whatever I wrote -- five 800-word columns a week, plus an occasional op-ed piece or off-television feature -- despite an occasional upwelling of bullshit and self-indulgence. I came and went on my own schedule, like a private contractor. It was amazing. Still is. The P-I was a special place back then.

I became immersed, consumed, to the frequent consternation of Justine. I was either watching television, reading/writing about it, or chatting up, interviewing, or lunching with those involved. Everything feeding “the maw of the monster,” as the late great Eric Sevareid once described it. As expected, chronicled and critiqued the churn of new shows, stars, and other product, but also tried to cover the entire broadcast industry -- especially TV’s growing role and reach in politics and the culture. The Fairness Doctrine, and the “public airwaves” were issues at the time, before cable TV began expanding the spectrum of choices, more often in the down-market direction.

For the first time in my journalistic career, I had this forum, this pulpit and it was a heady experience. Sometimes too heady. Too easy to take oneself too seriously. The network and local station PR folks were extremely solicitous, and high-end junkets took us critics (and occasionally, family) to Los Angeles, Hawaii, London, New York, Miami, and West Germany. The bar -- so to speak -- was still set pretty low back then, for what was ethically acceptable in the way of freebies, outside the newsroom at least. The junkets in L.A., where the networks rolled out next season’s new shows and stars, were a couple of weeks of non-stop interviews, tours, screenings, obscene amounts of food and booze, and cocktail party chats with Nimoy, Shatner, the M*A*S*H folks, whoever. Very heady.

The dichotomy of trying to save the world from television while soaking up its martinis and shrimp cocktails might occasionally furrow the brow, but not much.

There was no shortage of material. Television was in the midst of its own revolutions. The majority of Americans was now getting most of its news from television -- a scary thought. And even folks high in the TV news business -- Mike Wallace and ABC’s news boss, Av Westin, for two -- agreed that anyone who relied on TV news was not properly informed.

Nicholas Johnson, a controversial FCC commissioner from 1966 to 1973, who has been trying to save the world from television his entire career, called TV “the biggest drug pusher in the country,” and that was back in the early 1970s. These days, 35 years later, the drug, advertising, and media industries have made it even bigger, thanks to a compliant Congress.

All the studies of this communications phenomenon, however, registered a big-time downside, especially for kids -- fattening their bodies, stultifying their minds, creating more bullies, while selling them junk foods and toys.

But for the first time, the carnage of war was being beamed into America’s living rooms nightly and the images from Southeast Asia were fueling the country’s discontent. President Richard Nixon launched his own war on TV news coverage and commentary on November 13, 1969 -- shortly after I joined the P-I -- when Vice-President Spiro Agnew said in a Des Moines speech: “In the United States today, we have more than our share of the nattering nabobs of negativism.”

When the Washington Post was dogging Richard Nixon over Watergate, he went after the federal licenses of the paper's two television stations.

Television had begun shedding its lily-white image in the mid-1960s when Bill Cosby paired with Robert Culp in “I Spy.” And on a 1968 NBC special, Petula Clark made news when she casually touched guest Harry Belafonte on the arm, the first biracial bodily contact on American television. The sponsor, Chrysler, had wanted to cut it, but Petula said, “No.”

PBS’s “Sesame Street” premiered on November 10, 1969, providing a much-needed antidote to commercial kidvid. “All In the Family,” which debuted in January 1971, examined hitherto-taboo subjects such as racism, abortion, and homosexuality. It was phenomenally popular and spawned several spin-offs.

“Monday Night Football” debuted in 1970, hosted by Howard Cosell, Frank Gifford, and Don Meredith, three of the most mismatched performers ever to share a mike. With a year as a TV pundit behind me, and already pretty close to omniscient about the public pulse, it was obvious that “MNF” would be more football than the country could handle and was doomed.

“Reality TV,” one of the major scourges of post-2000 television, was kick-started back in 1973, when PBS broadcast “An American Family,” a tabloid-juicy, fly-on-the-wall series about the Louds of Santa Barbara, who split up on camera and who numbered a flamboyant, lipsticked son named Lance among their five progeny. Lance went on to a sort of career in the gay community.

This communications marvel also had a spookier side. Jerzy Kosinski wrote of it in 1971, with his anti-television satire, “Being There.” It was made into a movie in 1979, produced by and starring Peter Sellers, one of his finest performances.

Kosinski said “Television is slowly blurring our distinctions between reality and unreality,” and he got that right. He said, “I write for a certain sphere of readers in the United States who on average watch seven and a half hours of multichannel television per day.” In 2009, family viewing was up around eight hours a day.

(In a collection of about 20 critiques of the Being There movie on the “Rotten Tomatoes" website, in January 2010, all of them missed that point, whatever that means.)

Another iconic take on television was the 1976 movie satire, Network.

There were 59 million television sets in the country in 1970, less than half color, and 75 million when the decade ended. Cable television, promising clearer pictures and commercial-free viewing, was in its infancy, with 4.5 million customers, and would grow to 14.1 million in 1979. Seattle’s hills, blocking signals for homes in the valleys, encouraged local cable’s development. Like most major cities, Seattle had three network stations, a couple of independents, a Public Broadcasting station, and some cable, which picked up stations in Bellingham and Vancouver, B.C. KING-TV’s Ancil Payne remembered “The money was coming over the transom.”

In April 1970, however, Congress banned cigarette advertising on television or radio, starting on January 2, 1971. The money stopped coming over the transom and Seattle-area stations were further whacked by the Boeing Bust.

At the time, KING-TV, the NBC affiliate and pioneering flagship of Dorothy Bullitt’s TV-radio empire, was in even deeper trouble. In addition to bleeding red, KING-TV had lost its long-held No. 1 news ranking, internal disarray had driven out some executive talent, and morale was low.

Ancil Payne, a giant in Seattle’s (and NBC’s) TV annals, was brought in to right the ship and he did, while ramping up KING’s established progressive-aggressive presence. KING had hired some excellent news talent and Payne was in the newsroom regularly, rallying the troops.

Dorothy Bullitt’s son, Stimson, was running the station in the mid-1960s and he had made news in 1966 with a politically chancy anti-Vietnam War editorial. He also diversified the staff, adding women and blacks. Among the hires in 1968 was Jean Enersen, who became the anchorwoman in 1972, the first woman in the Pacific Northwest to hold such a post, and one of the first in the country. She went on to an illustrious career at the station, and in 2010, in her mid-60s, was still at her desk.

Payne had brought Charles Royer up from Portland as the news analyst. Royer, who went on to be serve three four-year terms as mayor of Seattle, remembered the KING-TV newsroom as “sort of bizarre, a mixture of Hunter Thompson and ‘Animal House’ ... whiskey in the desk drawer, wild parties. The station manager and the ownership cared about news, liked it controversial and tough, and we loved it.”

They also produced a substantial body of award-winning, establishment-rattling television journalism. Justine and I socialized some with Don McGaffin and his wife, Anne, and others. Also in the KING-TV newsroom for about a year during the Royers’ tenure was David Brewster, an assignment editor who would go on to found the Seattle Weekly and become a major civic and cultural voice in the city. “There were some very good people,” Brewster said. “Mike James, Al Wallace, Phil Sturholm, Kathy Wynstra, Don McGaffin. It was a lot of fun.”

But television was changing, and so was Royer. “The station began to buy into all that happy-talk personality (news) ... . Anybody could see what TV was starting to become. I knew all those people running for mayor and thought, ‘I can do that better than they can.’ It’s an unnatural surge of ego you have to have.”

KING’s was the TV station milieu in which I felt most at home.

Dorothy Bullitt had a strong streak of noblesse oblige and KING-TV’s public service department was first-rate. Its director for a time was Emory Bundy, an earnest, professorial sort, who would later reappear as another big pivot point.

KOMO-TV was the ABC affiliate, owned by the Fisher Flour family. Still is. It was pretty straight-arrow, responsible. Still is. It occasionally tries to stretch or morph into something more upbeat, but seems glued to a down-home rhythm. Ray Ramsey was the weatherman -- Hayhead Ray -- and he was some kind of metaphor for KOMO’s ambience. A blogger named Tim Hunter observed, “Ray always wore sports coats that looked like he was about to sell you a ’59 Ford Fairlane.”

Bruce King was its long-time sports editor, though he tried a year in the big time -- WABC in New York in 1981 -- returning to KOMO until 1999. I heard somewhere that Bruce was the inspiration for Joe Piscopo’s sports commentaries on “Saturday Night Live,” but that story may be apocryphal.

KOMO had a good news staff, however, and also took its public service commitment seriously.

Margaret Haggerty was the media person; gracious, polite, old school. Nice lady. Very KOMO.

It was at KOMO that I met Nate Long, who was producing a public affairs show, “Action Inner City.” The project was an admirable addition to KOMO’s public-service schedule. Though, like similar programming, it appeared during television’s Sunday afternoon ghetto time.

Nate was about my age, early 40s, ex-Air Force MP noncom, who had landed in Seattle after he retired at nearby Paine Field. He had grown up in Philadelphia’s black gang world, with low aspirations. An uncle was a railroad porter, which was as high on the socio-economic scale as young Nate could see. He escaped by joining the Air Force and, with his skills, résumé, and physical presence -- built like a barrel -- he was a natural for the military police. Nate joined about the time Harry Truman integrated the armed forces, in 1948. (“This white guy, he was surprised that blacks took showers.”)

While stationed in Japan, he got into martial arts and earned a black belt in judo. Along the way, he lost some of his Philly tough-guy and absorbed the judo-kan’s philosophy: respect for others, balance, discipline, responsibility, humility, to neither bray at success nor weep at failure. He started teaching judo -- and its ways -- to inner-city kids through the Central Area Motivation Program, a Model Cities project that came out of Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” war on poverty. (He also taught outside the ghetto and Theo spent a year under his tutelege. “A cool dude,” Theo remembered.)

Nate was kind of a black Mister Miyagi -- in “The Karate Kid?”

There were few blacks in television in the 1960s, and, as he watched the coverage of racial riots roiling the country, he saw “the power of the media to do whatever they want to do.” He began to see information, communications, media, as a way out of the ghetto for kids and a need within it. “In the ’60s,” he said, “There were not many blacks interested in communications. After the riots (Watts in 1965; Newark and Detroit in 1967), you began to see a couple of black people on the air.”

He cobbled together what he had learned -- “on the street, in Japan, in the Air Force” -- picked up the rudiments of cinematography, and, in 1970, opened Oscar Productions, a TV training program for inner-city kids. Its “Action Inner City” lasted for 10 years on KOMO-TV.

Many of his students went on to careers at KOMO and other stations. Among them was Norm Rice, who also went on to become Seattle’s first black mayor in 1990. Norm was about 21, fresh out of Highline Community College, and working on an Urban League project examining minority access to the media when he first met Nate. “He was a great teacher,” Norm said. “He was one of the fundamental building blocks of my life.”

Nate’s style was “inclusionary not exclusionary.” He said, “I teach my students, ‘Everyone in this classroom has a skill. What is it? One guy can talk, one guy write, one guy is technical, somebody likes sound. Wouldn’t it be nice to know how all these people can get together and do something. Anything.’”

Rather than competing with each other, his students were encouraged to help one another. His method was Socratic. “You have to make them think about things. I’m forcing them to think and they hate it.”

He tried to address some of problems in the black community. CPT, for instance. Colored Peoples’ Time. “I have a 15-minute rule. If you’re not there, I go home. If I stay and you’re 30 minutes late, and you spend 15 minutes talking about why you were late, that’s 45 minutes I’ve lost out of my time, and you have invested nothing.”

Nate and I did a couple of black-white dialogues on the show -- another jump-off-the-cliff experience and, again, one for which I was not particularly qualified. And no memory of what was said or accomplished.

Nate also produced two award-winning television series on black history, South by Northwest and The Second Time Around.

He wanted to learn Hollywood cinematography, took himself down there, and started learning the industry from the ground up, as a go-fer, first on blaxploitation films and then more salutary fare. He choreographed stunts, was a stuntman, working his way up to a couple of second-unit director credits.

He returned to the Pacific Northwest in 1985 and put together a two-year film program at Seattle Central Community College, and directed it for 10 years. He later organized similar programs at Texas Southern University and Texas A&M University.

Nate Long died of leukemia in November 2002. He was a mensch.

The CBS affiliate was KIRO-TV, then owned by Bonneville International Corp., the media arm of the Mormon church. It has since changed hands a couple of times. Its manager was Lloyd Cooney, who provided balance for Ancil Payne’s animated progressive rantings over on KING-TV with a more schoolmasterish, stiffer, conservative take on the day’s events. KIRO-TV’s environment was chilly and I never felt comfortable with their style. One of the memorable moments was a news release about the hiring of a 26-year-old “veteran newsman.” Veteran? At 26?

I got into an unfortunate pissing contest with Cooney -- another display of excessive arrogance, in retrospect -- and was banned from the station.

But I met Saul Haas, who had sold his KIRO holdings to Bonneville in 1964, and he was a treat for too-brief a period. He was still chairman of the KIRO board, but he was titular and had nothing to do with the station’s management. He was in his mid-70s, wearing down after a full, rich -- often controversial -- life as a broadcaster, journalist, political operative, and confidante of the powerful. His mind was still sharp, he still enjoyed a drink or two, and some productive discourse. Val Wright, one of KIRO’s PR men back then, said Saul was smarter drunk than most men were sober, and that he never left a meeting with Saul without learning something. I could say the same.

Chet Skreen, the Seattle Times TV writer when I was at the P-I, remembered him as "one of broadcasting’s most colorful characters." He had been called “ruthless,” “tyrannical;” “despotic,” and the record lends some credence, but he was an encouraging, chiding, amusing, philosophical pleasure during those lunches.

Saul had hoboed west from New York’s East Side after finishing high school, was a sharp lad, and he was drawn into journalism, which led him into politics. In 1932, at age 36, Saul managed the successful campaign of Homer Bone for U.S. senator and went to Washington, D.C., as Bone’s chief of staff.

Bone was a populist Democrat who has been called the “father of public power” in the Pacific Northwest. Saul also was hooked on radio and spent considerable time around the Federal Communications Commission, learning about the business and its politics at ground zero.

Haas and Bone also mentored another up-and-coming politician -- Warren G. Magnuson -- who won a seat in the Washington state House of Representatives in 1932. Magnuson also was intrigued by radio and used it in his campaign. In Warren G. Magnuson and the Shaping of Twentieth-Century America, journalist Shelby Scates quoted Magnuson as saying that the three dominant influences in his political life were Alexander Scott Bullitt (husband of Dorothy Bullitt), Homer Bone, and Saul Haas. They left a legacy of like-minded politicians and businessmen who continued the progressive dynasty into the twenty-first century.

Loren Stone, a long-time broadcasting hand and one-time Haas business associate, once mused: “He had an amazing capability of attracting famous people, people of great competence and ability, as friends. His wall was covered with signed photographs of everybody, mostly politicians, from FDR on down.” The picture of Lyndon Johnson was signed, “To Saul, friend, philosopher, sage ...” Haas was a fishing, hunting, and drinking buddy of Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas.

In 1934, Haas obtained KCPB in Seattle, a destitute, daytime-only 100-watter, dreaming of a network of progressive stations. The network never materialized but by 1941, the station -- now KIRO -- was a CBS affiliate and a 50,000-watter. His broadcast acquisitions were controversial, including Channel 7, the last VHF (very high frequency) TV license in Western Washington, in 1957.

Lyndon Johnson appointed Saul to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting board and he was reappointed by President Nixon. He and his wife created the Saul and Dayee Haas Foundation, which provides assistance to needy students.

Saul died in 1972.

The most out-of-character character to appear in that period was Nicolas van Gelder, who was doing PR for Ma Bell, when it was still a monopoly. (Remember that great bumper sticker with Ma Bell’s blue-bell logo? “We don’t care. We don’t have to.”)

After earning an M.A. in Asian studies and teaching for a while in British Columbia, he came to Seattle with wife and 4-year-old child to work on his Ph.D. in Buddhic-Indic studies under Edward Conze, then at the University of Washington. Conze, who could speak 14 languages, including Sanscrit, by age 14, was one of the world’s foremost translators of Buddhist texts. Conze also was interested in Theosophy.

But the wife headed south, leaving Nicolas with a young child, a need for a job, and the end of his academic pursuits. He somehow got into writing industrial films which led him to Ma Bell. I had difficulty reconciling an English-accented, English-mannered Buddhist scholar and Ma Bell PR. Still do.

Nicolas was born in Nainital, India, and his mother was from English colonial stock. His father came from a Dutch East Indies colonial family and was raised on a sugar plantation on Java. His family members, four generations of them, were mostly devoted Theosophists. Nicolas’s paternal grandmother, great-grandmother, and his Aunt Dora were clairvoyants -- not that uncommon among Dutch families.

It was Nicolas’s destiny to get an education, according to his grandmother, who apparently had access to such information, and Nicolas did. And then some. Unfortunately, like many sons of the Raj, he was shipped off to England and an aunt at age 7, seeing his parents only rarely after that.

I first met Nicolas at the screening of one of AT&T’s uplift TV specials, which was about to air. After the screening, three or four Ma Bell PR guys repaired to Rosellini’s 410 -- then Seattle’s power-lunch restaurant -- with Chet Skreen and I, and everyone came out sometime later, well-oiled and well-fed.

Nicolas enjoyed Bombay gin and maundering through the world of ontology and related concerns, and so did I. He was another of life’s major pivots and a lifelong friend.

Radio occasionally provided newsworthy fodder -- to me, at least -- and KAYE, a small, right-wing station in Puyallup, certainly did. A local citizens’ group had challenged KAYE’s license in 1960, charging the station with lying to the Federal Communications Commission, airing anti-Semitic propaganda, and other transgressions. Aiding and abetting the citizens group was the Rev. Everett C. Parker, head of the United Church of Christ’s office of communication and one of the foremost scourges of right-wing radio. The FCC got around to hearing the challenge in 1970 and Administrative Law Judge Ernest Nash came out from D.C. to preside.

The case dragged on for nearly three years, Nash and I stayed in touch, and we became good friends. Ernie was a Hungarian Jew, born there, who emigrated to the States with his parents as a baby. His father was a baker, Ernie learned the craft as a boy, and his baguettes rivaled those found on the streets of Paris. We shared a somewhat similar Southeastern European heritage, upbringing, the second-generation thing, name change (his from Nadovitz, mine from Cekovich), no fear of vociferously expressing his opinion, and a sometimes-supercilious, curmudgeonly mien. Ernie called me his doppelgänger. His 10 years as an FCC administrative law judge, 30 years total in federal service, and a wide range of literary and political interests, gave him plenty to talk about.

Ernie also opened another channel of connections, when he was in Seattle in November 1970 for a hearing on the license renewal of KRAB-FM. It was an alternative station -- a “free forum broadcast station,” it called itself -- founded in 1962 by Lorenzo Milam, a somewhat-kooky radio activist dubbed “the Johnny Appleseed of community radio” by Broadcasting magazine. KRAB’s “extraordinarily diverse programming” reflected Milam’s taste for “the wry, the wacky and the eccentric,” said a piece on Salon.

The FCC was challenging a full license renewal because of obscenities aired on three programs -- two of them by reverends, incidentally. In a 22-page decision issued March 22, 1971, Nash granted KRAB a full license renewal. The case became a part of the Seven Filthy Words brouhaha and a string of court challenges going up to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Also at KRAB was a radio engineer/on-air talent, Jim Hatfield, who became friendly with Nash. Hatfield’s father, Jim Senior, had done the engineering when KRAB first went on the air. In 1973, Hatfield and Ben Dawson, another KRAB engineer, formed a company specializing in telecommunications and electromagnetic engineering. They were sixties kind of guys, KRAB kind of guys, well-read and well-informed, totally engaged in the world, certainly the world of telecommunications, and vociferously liberal. And maybe because of the KRAB thing, they tolerated some eccentricity around the shop. Hatfield, Dawson, and other partners have been all over the globe climbing towers, from Seattle to Djibouti, Kazakhstan, and Kabul, never lacked for something to gab about and enjoyed a robust dialectic. Discourse. Repartee. Persiflage. Bullshit. Whatever. My kind of people.

When Ernie retired in 1973, he and his wife, Marge, moved to Seattle, Marge took a job as librarian at Hatfield, and Dawson, and Ernie starting hanging out with the H&D crowd. I did too, and a later partner, David Pinion, also would become a good friend. It was Pinion who went to Kabul, first in 2002, soon after the Taliban disappeared into the hills, to determine how to rehabilitate two old Soviet radio stations with new 600-kilowatt transmitters, and then again in 2003 to commission the stations. The stations could be heard as far away as New Delhi after the work was completed

Ernie Nash died in 1997.

The most outrageous experience of the TV years was Dick Balch, a Federal Way Chevrolet-Fiat dealer who made a huge pile of money during the Boeing Bust, by running whacky, 10-second spots on local TV stations. Long-haired and moustachioed, he would stand by a car with a sledge hammer, in a devil’s suit or nightshirt, say something on how to “air-condition these small Italian cars,” drive the hammer through a Fiat windshield, and cackle maniacally. (There’s an old line in the garage business, about Fiat being an acronym for “Fix it again, Tony.” ) He built a sumptuous, Hollywood-Hills-worthy bachelor pad on the Sound, drove a bright yellow Ferrari for a while, and was a local folk hero among the kids. He posed nude for the Seattle Flag, an alternative newspaper, and was in high demand as a speaker. “High school assemblies are outa sight,” he said for a piece I did on Balch for TV Guide in ’72. He later spent some years involved in lawsuits over the business.

At the P-I, I shared an office with Shelby Scates, in what was called the Northwest Wing of the old building at 6th Avenue and Wall Street. Scates, Mike Layton, and others were doing some commendable muckracking under publisher Dan Starr, but that slowed when Virgil Fazzio took over.

Shelby lived a half block up 8th W with his wife and two daughters and we shared a beer or two regularly.

Columnist Emmett Watson was on one side of us, and a pleasant, old-shoe curmudgeon he was. Earl Hansen, a onetime Lutheran minister and the P-I’s anticlerical, antiwar religion editor, was on the other. Hansen’s diatribes, illustrated by equally antiestablishment cartoonist Ray Collins, took on fundamentalists, cults like Scientology, and organized religion in general. The editorial department was close by, as were the weekend entertainment section folks.

Nancy Hevly remembered “a lot of fun, a lot of crazies and almost crazies. Those long lunches ... Sally Raleigh and her three martinis.”

Jean Godden, whose reminiscences of those days appeared on the Crosscut website (January 15, 2009), said the newsroom “was the incarnation of Ben Hecht’s ‘Front Page,’” and the “P-I at the time employed a crew of journalistic misfits and literary geniuses ... ." She added: “Names still resonate: novelist Tom Robbins who sat on the rim and wrote memorable headlines; Frank Herbert, famed for the Dune series; columnist Emmett Watson, who invented Lesser Seattle; copy desk chief Darrell Bob Houston, who styled himself as “D.B.” after writing about D.B. Cooper, the guy who hijacked an airliner, extorted a ransom and parachuted into the unknown.”

Tim Egan, who came to the P-I in the late 1970s and went on to become a New York Times columnist and prize-winning author, said “There were some terrific writers there ... And the paper let you write. They gave people as young as I was a chance to really go to town.”

Robbins was on the copy desk, and when he asked me to write the P-I’s review of his new book, Another Roadside Attraction, I was flattered out of my shoes and did so.

Godden was no slouch herself. She came to journalism and the P-I later in life, in 1974, and served as urban affairs reporter, business editor, editorial writer, and columnist. She was hired away by The Seattle Times as a columnist but, in August 2003, she saw the writing on the wall for columnists, newspapers and the Times, and quit to run for Seattle City Council. In March 2010 she was in her second term and still enjoying governance. “At least it’s not boring.”

It was a “golden age” for the P-I, said John Caldbick, a onetime copy boy and later an attorney.

The main watering hole was the Grove, a dim, smoky bar in the Grosvenor House across Wall Street, otherwise known as the Grave. Don’t remember ever being there, which was daily or more, without a few P-I folks in attendance.

Meanwhile, back at 1104 8th W, we settled in to the urban family scene, and as close as we’d come to “normal.” For Theo, finally with something like stability, it was “all good.” He played Little League baseball and football, tried the judo with Nate, did well in school, made his own circle of friends and families on the southwest corner of Queen Anne -- the Heidens, the Peabodys, the Hansens, the Woods, the Sidrons. When he was around 12, he got a flunky job at Les Ruthford’s Lake Union Air Service and discovered flying. He still remembers being allowed to taxi a float plane down the lake, in the left seat, and it hooked him on flying. He went on to become a bush pilot (and fisherman) in Alaska.

Justine, now heavily into belly dancing, happened on a UW folk-dance student, Mary Dossett, and they formed a belly-dancing troupe, Baladi, which performed at festivals around the area. Justine also did an occasional gig at local Middle Eastern restaurants. She had a natural flamboyance and was good at it. Only thing was, much of whatever she made went back into costumes, jewelry and records of Middle East music. Neither of us paid much attention to fiscal prudence.

The Volvo somehow gave way to an International Harvester Travelall, an early SUV and one of the great old gas-guzzling behemoths of autodom. It was finally replaced by a more reasonable Chevy Vega, from Dick Balch.

The Africas -- Spike and Red -- appeared on the scene in 1970. Around 1967, I had met Spike at the No Name Bar in Sausalito, another of my homes away from home – and his – when I worked for the San Francisco Chronicle. Spike was a semi-professional old salt, with an endless repertoire of sea stories and a thirst for scotch. Red, with her own peripatetic bona fides, also would appear on occasion. The Africas were best-known for joining Sterling Hayden in 1958, when he defied a court order and set sail with his four children for Tahiti aboard his schooner “The Wanderer.” Spike was the mate and Red handled everything else, including the Africa’s own three kids.

Red’s father, E. Ryan Dunham, a chiropractor, had done well enough to buy three acres on Lake Washington at Juanita Point during the Depression. Red had inherited the property, along with its cabin and a stirring view down the dock, across Lake Washington to Mount Rainier. Spike tended a bountiful garden, chopped wood (“like the Kaiser in exile”), wove incredible macrame, groused about his life away from “the saloons,” and entertained whoever showed up. And Red, as I said in a piece on them (“Spike Africa,” P-I, May 5, 1974), had brought her own “cockamamie credentials” to their union. A Seattle University graduate, she had been a translator, welder, nurse’s aide, and real-estate saleswoman, made a fantastic onion soup, and generally ran the show.

We would spend many a delightful Sunday out there, sometimes with their kids, and/or members of their wide-ranging West-Coast-waterfront commune who passed through -- gyppo tugboatman Tony Carter and international fishing entrepreneur Hugh Reilly among them. I would have further dealings with them too. Boating friends and relatives from near and far would occasionally tie up at the dock. Memorable times.

But, as Joseph Heller said in his novel Something Happened, something happened.

Burnout? Six-Year-Itch? Couldn’t stand success? The old adolescent restlessness again? Whatever.

I had been covering TV for six years, one of the longer P-I TV-column tenures to that time, but Susan Paynter, who took it over, went 16. It had been mostly fantastic, trying to wrap one’s head around this Thing, this revolutionary change agent for our culture -- entertainment, information, politics, governance, consumerism, obesity -- all of it. The historic Vietnam War coverage, the historic Congressional Watergate hearings. The historic space shots.

But all this work and I not only wasn’t saving the world from television, but probably making it worse. There was some progress, of course. TV drama had progressed from the rusty, simplistic “Ironside” to the more sophisticated, snappier “Rockford Files” and “Baretta.”

And comedy came a long way: The ground-breaking Norman Lear dynasty -- “All In the Family,” “The Jeffersons,” “Maude,” etc. “M.A.S.H,” “Saturday Night Live,” “Mary Tyler Moore,” “Barney Miller.”

“M.A..S.H.,” developed by Larry Gelbart, (“A Funny Thing Happened On the Way to the Forum”) appeared in September 1972 and lasted 10 years. Its final broadcast, February 28, 1983, was the most-watched TV show in U.S. history up to that time. I had a deeper-than-usual interest in the show because I had chatted at some length with Gelbart, Alan Alda, and. other cast members at some CBS bash and had later visited with Gelbart to talk comedy writing. His advice: “Bomb the shit out of every page with jokes.”

But there was more and more television coming. Cable and all its fallout, a lot of it not beneficial to the system.

In those six years, I figured I had watched more than 10,000 hours of television, watched about 140 shows come and go, and written more than a million column words, some good, some not so good.

But another cliff to jump off appeared. I’d winter-watch a salmon port for Peter Pan Seafoods at Port Moller, on the Alaska Peninsula, for nine months.