Harvey Manning was called a lot of things during his long and productive life, but bashful wasn't one of them. For well over 50 years, he was a combative advocate for conservation, harnessing his withering wit, acid pen, and no-holds-barred style to protect wilderness areas, from the deepest recesses of the North Cascades to the fringes of metropolitan suburbs. Manning was a prolific author, and his books combined practical advice on hiking and climbing with exhortations on the need to preserve wilderness. A long association with The Mountaineers Books and with photographer Ira Spring produced the famous 100 Hikes and Footsore series, and Manning's other books, articles, and essays covered everything from delicate wildflowers to epic political battles won and lost. Manning, alone and in collaboration with Spring and others, told generations of outdoors enthusiasts why to hike, where to hike, and how to hike. He believed that wilderness areas could be saved only through the creation of a broad constituency of supporters, people who had experienced the natural wonders of the Northwest and would fight to preserve them. Creating that constituency was his life's work, but near the end of that life he came to question whether his beloved wild places were being loved too much. His growing doubts about the wisdom of facilitating unlimited access to deep wilderness caused a rift between him and some of his longtime collaborators, and by the time of his death he had severed ties with both The Mountaineers Books and Ira Spring. But through it all, Harvey Manning's single-minded dedication to conservation and his willingness to take on anyone who threatened the causes he fought for inspired thousands to join the battle on the side of nature.

Ballard, Bainbridge, and the Boy Scouts

Harvey Hawthorne Manning was born in the Seattle neighborhood of Ballard on July 16, 1925, the only child of Harvey Manning (1904-1983) and Kathryn Hawthorne Manning (1906-1976). His mother's family spent summer vacations on Bainbridge Island, and that was where she met Harvey's father, a petty officer from Middlesex County, Massachusetts, serving in the U.S. Navy. After his military service, the senior Manning went to work for Simpson Saws, selling saw blades and lumber-processing equipment to the very industry that would become one of his namesake son's chief adversaries.

The Manning family returned to Bainbridge to live for several years during Harvey's early childhood, and some of his first memories were of exploring the island's beaches with his father and cousins. After returning to the mainland in 1933, the family settled in north Seattle. Young Harvey joined the Boy Scouts, and he and his father took frequent trips to the Cascades, camping and hunting. Many years later, Manning still remembered vividly what he called his "epiphany year." At age 12, while on his first Boy Scout camp-out, he took a solitary walk to the trail's end at Marmot Pass on the Olympic Peninsula:

"I came to a creek tumbling from under a boulder. Books told of explorers spending lifetimes searching for the Source of the Nile. On this, my very first mountain hike, I'd found the source of the Big Quilcene. I came to where the meadows ran out into a sky of sunset colors and I gazed down to the shadows of a great unknown valley, and out to a ragged line of peaks that might not even have names, so far as I knew. This was wilderness. I'd thought all the wilderness was in Darkest Africa, the Polar Wastes, the Roof of the World. But here it was, and here I was, and though not for years would I even hear the word, that evening at Marmot Pass must have been about as good an epiphany as any twelve-year-old Boy Scout ever had" (100 Classic Hikes, 229).

Manning stayed with scouting and reached the rank of Eagle Scout during World War II. He enjoyed the rough hiking methods of the day, traveling with minimal equipment, just enough food to keep one's strength up, enduring day-long trudges and nights spent in old feather bags that couldn't keep out the chill. Recalling these rites of passage in a 1991 interview, Manning said: "If you liked the mountains after that experience, you really liked them. For those of us who liked it, it was a lifelong commitment" (The Seattle Times, May 23, 1991). For as long as he was able to get out into the woods, Manning rejected GoreTex and polypropylene in favor of wool and canvas.

College and Beyond

Manning attended Seattle's Lincoln High School and received a degree in English literature from the University of Washington in 1945. In 1947 he married Betty Williams, another English-lit major and fellow hiking enthusiast. They settled down in Seattle, then moved to a wooded site on Cougar Mountain in the early 1950s, where they would live for the rest of their married life. Manning took on a series of jobs, including working at local radio stations and selling books. He even worked briefly for a defense contractor during the height of the Cold War, writing instruction manuals for intercontinental ballistic missiles.

In the early 1960s, Manning was hired by the University of Washington, where over the next 10 years he worked a number of jobs, including writing biennial reports to the Washington State Legislature and editing Washington Alumnus, the school's alumni magazine (later called Columns). Although Manning's life's work would be protecting wilderness, his editorial commentaries in the magazine often revealed his strong views on the deep societal divisions of the 1960s:

"Perhaps no black man or white man who sees clearly into the future of race relations in the nation, the State of Washington, the City of Seattle — or the University of Washington — likes what he sees ... . The University can bring black students to campus and help them stay, it can provide minority employees with expanded opportunities for career growth, it can serve the Central Area with special resources of knowledge. Yet these are small nibbles at the big problem: that the University is a part and parcel of a society that continues to deny some of its citizens full and equal opportunity for individual development" (Washington Alumnus, Spring 1968).

Manning tackled his first major outside literary project at the beginning of the 1960s. He and Betty Manning had joined The Mountaineers in 1948, and with his background in literature he was a natural choice to work on the club's first book, a compilation of accumulated notes, pamphlets, and lectures about mountain climbing. The first edition of Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills was published in 1961, a comprehensive guide to mountain climbing with information and advice on everything from planning an expedition to tying knots that wouldn't let you down when it mattered most. The book proved to be an instant (and enduring) success. The sales of that first edition generated enough income for The Mountaineers to pursue other publishing ventures, and the seventh edition of this seminal guide, updated in 2003, is still available in bookstores.

Building a Book Business

When the profits from The Freedom of the Hills started coming in, Manning wanted to make sure that the money didn't disappear into the well of The Mountaineers' general operating budget. He fought for and won the establishment of a Literary Fund Committee that would use the profits from The Mountaineers' publications to support the development of further books. Although it wouldn't formally change its name until 1978, the Literary Fund Committee marked the true birth of The Mountaineers Books, which today is one of the leading publishers of books devoted to outdoor recreation, active lifestyles, and conservation advocacy.

With a publishing enterprise in place at The Mountaineers, Manning was able to turn his attention to writing and editing, while still keeping his job at the university. As the Literary Fund Committee mulled over what do to next, someone at The Mountaineers came up with a copy of a British guide describing 100 hikes in the Alps. This provided the inspiration for 100 Hikes in Western Washington, the first of a now-famous series of hiking guides. The primary author of this first volume was Louise B. Marshall, another Northwest hiking legend, who was instrumental in the founding of the Washington Trails Association. Ira Spring, who with his brother, Bob, was making a name for himself as a talented outdoor photographer, handled the photography, andManning contributed material on hikes that he had taken. When the book was released in 1966, it became an immediate hit, selling 15,000 copies in the first six months.

The success of 100 Hikes in Western Washington was not universally welcomed. The Northwest's trails had been the exclusive preserve of relatively few cognoscenti, for reasons explained by Ira Spring's daughter, Vicky:

"Trailheads were very hard to find in the early 1960s. Logging roads were poorly signed or not signed at all. New roads were made, but not signed. People headed out into the forest and got very lost. Maps were out of date before they were published. So, the first 100 Hikes book was heavy on driving instructions and low on trail descriptions" (Vicky Spring, email to author).

Teaching people how to get to the trailheads resulted in huge growth in the number of hikers on the trails themselves, and what had once been areas of relative solitude soon became popular destinations for hordes of new users, many of whom did not share the "do not disturb" ethos of the earlier, hardcore backcountry hikers. It was not long before hiking purists took to calling the book 100 Hikes Not to Go On. Once the cat was out of the bag on the location of the trails, there was nothing to be done but to expand the offering, hoping to disperse the crowds to hundreds of other trails around the Northwest. This necessity became the inspiration for the extension of the 100 Hikes series, a publishing effort that would continue on for more than 30 years.

Manning and Spring, and many of their contemporaries, were strategic, long-term thinkers when it came to environmental protection. Although there doesn't seem to be a specific "aha" moment, the opening up of more and more trails to a broader public came to be justified as a way to create an ever-growing constituency of generations of hikers who would fight to preserve the areas to which they now had access. The problems that came with increased use, including noise, litter, and damage to fragile ecosystems, could not be totally avoided, but many considered them an acceptable tradeoff for the political power that flowed from sheer numbers.

Manning used the 100 Hikes series (as he did with almost everything he wrote) to try to educate the public on how to use the wilderness wisely, to step lightly, and to leave it as it was found. In the introduction to Best Winter Walks & Hikes: Puget Sound, the last book of his long collaboration with Ira Spring and The Mountaineers, Manning, in his usual blunt manner, answered those who objected to being lectured on wilderness etiquette:

"To readers' complaints that they want directions on where to go, not lessons in how to behave, we answer, 'If you don't want sermons, don't go to church.' To those who disagree with our politics, we say, 'Publish your own books.'"

For more than 40 years, Manning tried mightily to harmonize the contradictory goals of opening up the wilderness to thousands of new hikers while trying to preserve those same wild places in a natural and undisturbed state. But they were ultimately irreconcilable, and this was to have sad personal consequences for Manning and some of his closest associates.

Provocateur with Poison Pen

Although Manning had been hiking all around the Northwest since his early youth, his passion for preserving the backcountry came somewhat later. In a 1996 interview, he didn't provide a specific date for his second wilderness epiphany, but he remembered the moment in fine detail:

"I can recall the precise point at which I stopped being a hiker and climber and became a conservationist. It was on a heather slope high above White Rock Lake. There was beautiful wilderness all around me; lakes, forests, mountain ridges. Suddenly I saw this huge brown blight, an obvious clearcut, way down there by the Suiattle River. I thought 'My God, they have gotten this far already. They will take it all if someone doesn't stop them'" (Potterfield, "The Warrior Writer," p. 62).

And so, at some relatively early point in his life, Harvey Manning began his decades-long battle to stop "them" -- the loggers, the miners, the captive agencies of government that he saw frittering away the nation's natural heritage -- and later, the mountain bikers, the off-roaders, and the ever-growing number of tech-laden weekenders who he came to believe were degrading his beloved wilderness.

He was less a persuader than a provocateur. He pounded out his long manifestos on an old mechanical typewriter (well into the computer age, he compromised and started using an electric typewriter). His forewords to the 100 Hikes series (he called them "fighting forewords"), and much of the text within, went far beyond mere description to become passionate advocacy.

In interviews and in his writing, Manning could be brutally scornful of those who opposed his views, and he was not above ad hominem attacks. Upset at the amount of public money being spent on playfields rather than conservation, he once derided "little soccer Nazis." On another occasion he called a Bellevue city councilman "a hooligan" (The Seattle Times, September 16, 1996). He wrote that former National Park Service director George Hartzog’s idea of wilderness was "sitting on the veranda of a chalet, cold martini in hand, smoking his cigar, and watching the sun set behind a picture postcard" (Wilderness Alps -- Conservation and Conflict in Washington’s North Cascades).

To Manning, the need to preserve wilderness was so self-evident that he had no tolerance for those who disagreed with his goals, and little tolerance for those who disagreed with his tactics. His single-mindedness ensured that he was not universally liked. Kurt Springman, the Bellevue councilman who had incurred Manning's wrath, called him "one of the more intolerant and divisive people around ..." on conservation issues (The Seattle Times, September 16, 1996). But Manning didn't care what others thought, telling one interviewer "I'm not trying to be nice or make friends. I'm trying to save wilderness" (Potterfield, "The Warrior Writer," p. 58).

Working Well with Others

Despite all this, Harvey Manning was an able collaborator, and over the years he worked on conservation issues with many individuals and organizations that shared his broader goals, if not always his incendiary tactics. He wrote, co-wrote, or edited dozens of book and hundreds of articles. Even before the first 100 Hikes book was released in 1966, Manning had written the text for The North Cascades, a collection of photographs by Tom Miller, published in 1964 by The Mountaineers. He later noted that, "For most of the nation, this was the first revelation that there were peaks of that kind in the United States" (The Seattle Times, May 23, 1991).

The following year saw the publication of The Wild Cascades: Forgotten Parkland, a coffee-table book published by the Sierra Club, written by Manning, and lavishly illustrated with photographs by Ansel Adams, Bob and Ira Spring, and others. This and The North Cascades volume that preceded it were widely credited with introducing the Cascade Mountains to a nation that hardly knew they existed, and they were considered by many to have been a significant factor in mobilizing support for the creation of North Cascades National Park in 1968. But Harvey Manning was rarely satisfied. He later spoke of his misgivings over what he saw as a limited success:

"In 2000, they will say of the North Cascades Conservation Council, 'You were too timid. You compromised too much. You should have been more far-sighted, more daring.' I hereby place on record my personal apologies to the year 2000. In our defense, we will then only be able to say, 'We did not ask for protection for all of the land we knew needed and deserved protection. We did, for a fact, compromise in the name of political practicality. We tried to save you as much as we thought possible'" ("Brief History of the North Cascades National Park").

In addition to his nearly 60-year membership in The Mountaineers, Manning was a founding member of the North Cascades Conservation Council in 1957 and served for many years as editor of its journal, The Wild Cascades. He belonged to organizations with the international reach of Friends of the Earth, and in 1979 cofounded the Issaquah Alps Trails Club, with the much more parochial goal of preserving nature on Cougar, Squak, Tiger, Taylor, and Rattlesnake mountains and their surrounding areas. It was Harvey Manning who had the canny public-relations sense to attach the majestic "Issaquah Alps" label to these five foothills of the Cascades, the highest of which barely tops 3,000 feet.

A Hand in Everything that Mattered

Manning was such a prolific writer and was so deeply involved in conservation activism that a full account of the last 40 years of his life would merit a book, and will no doubt get one. He had a hand in nearly every major Northwest environmental campaign of the last half of the twentieth century. He was often in the center of the action, engaging in the verbal equivalent of hand-to-hand combat with logging and mining interests, property developers, government agencies, and, at times, fellow conservationists. He fought some battles from the fringes, lobbing in his rhetorical grenades while leaving to others the frustrating and time-consuming work of negotiation and compromise.

Manning didn't always win, and he rarely got everything he wanted, but he was always in the fight. As noted, he played a critical role in the establishment of the North Cascades National Park in the 1960s. He fought for the Alpine Lakes Wilderness Area, established in 1976. It has been said that President Gerald Ford (1913-2006) had decided to veto the Alpine Lakes legislation, but changed his mind after then-Governor Dan Evans (1925-2024) gave him a copy of The Mountaineers' 1971 book The Alpine Lakes, written by environmentalist Brock Evans (b. 1937), edited by Manning, and beautifully illustrated with photographs by Ed Cooper and Bob Gunning.

Manning was also a leading figure in the fight for the 3,000-acre Cougar Mountain Regional Wildland Park (1983), the Washington Wilderness Act (1984), and the Mount Si Natural Resource Conservation Area (1987). In 1990, the Issaquah Alps Trails Club he cofounded staged the "Mountains to Sound March," leading hundreds of hikers from Snoqualmie Pass to Seattle. This movement resulted in the creation in 1991 of the Mountains-to-Sound Greenway, encompassing hundreds of thousands of acres along the Interstate 90 corridor, from the grasslands of central Washington to the Seattle waterfront.

One Last Fight

Given his combativeness, which advancing age did nothing to diminish, it is not too surprising but no less sad that Harvey Manning's last big fight was with his collaborator of over 40 years, Ira Spring, and with the publishing house Manning virtually built, The Mountaineers Books. The trigger was a seemingly minor disagreement over whether the word "winter" should be included in the title of their latest collaboration, the second edition of Best Winter Walks & Hikes: Puget Sound, published in 2002. As Manning explained it:

"Somebody decided they ought to put 'winter hikes' in the title, but they didn't read the text. 'Winter' was used on another guidebook by another publisher, and they [at The Mountaineers] thought — 'Hey, there's a new twist — winter'" (The Seattle Times, January 11, 2003).

Manning's dismissal of his 40-plus years collaboration with Spring was terse: "Ira and I were friends for nearly half a century, but not anymore. He's gone his own way. He's now a trail promoter, not an environmentalist." His criticism of his long-time publisher was equally abrupt: "I founded The Mountaineers [Books], but now they're interested in pushing product and only minimally interested in the opinions of people who prepare the product" (The Seattle Times, January 11, 2003).

Clearly, there was more to this than a petty argument about a book title. Manning had become increasingly uncomfortable with the invasion of the far backcountry by ever-increasing numbers of hikers. His thinking had evolved -- he was no longer certain that the trade-off of sacrificing wilderness solitude to build a conservation constituency was always the best way to go, particularly when it came to what he called "the deeps." Spring, on the other hand, remained dedicated to the idea, and had coined the term "green bonding" to describe his consistent belief that those who were able to experience nature's glories would fight to preserve them.

Manning was not a person who recognized many shades of gray, but he clearly struggled to find a way to reconcile the competing interests he had embraced for so long. After Harvey's death, his son, Paul Manning, had this to say of his father's ambivalence:

"He always said that every new hiker that was brought into the mountains by his trail guides was a potential voter. Boots on trails leads to votes in the polling box. Every last stage of his writing was aimed at this goal, to bring them into the wilderness, starting with edge wildernesses, with day hikers and campers, to places where they could see the true wilderness from afar, and then get them in deeper and deeper.

It is true, as more hikers hit the wilderness, the other ideal, of saving the wilderness from those who love it too much, becomes a goal that all who love the wilderness must regretfully embrace. The practical way to do this, my father argued, was to provide alternative wildernesses, closer to home, to diffuse the impact away from those, like Mount Rainier, that were being loved too much" ("The Complexity of Harvey Manning").

In what may be the most insightful comment of all, Paul Manning characterized his father's evolution as "a deeply honest struggle of a man who committed his life to steering between these two mutually contradictory, and yet equally valid, positions" ("The Complexity of Harvey Manning").

Manning Remembered

The books, articles, and essays Harvey Manning wrote, edited, or inspired in his 81 years are too numerous to count. Failing health took him off the hiking trails in his later years, but his advocacy continued unabated. His last book, Wilderness Alps: Conservation and Conflict in Washington’s North Cascades, published the year after his death, recounted the history of the North Cascades and the 1960s battle to create North Cascades National Park.

Harvey Manning's death, from colon cancer, on November 12, 2006, was mourned by many:

King County Executive Ron Sims: "With the passing of Harvey Manning, we have lost a visionary giant in our struggle to save and protect our region's last best places" ("Sims Pays Tribute to Harvey Manning").

Rick McGuire, former president of the Alpine Lakes Protection Society: "I feel like one of the great cedars of the North Cascades has fallen. It’s hard to sum up a man like Harvey. He was a force of nature" (The Spokesman Review, November 15, 2006).

Andrew Engelson, writing for the Washington Trails Association: "Harvey was always a straight shooter, and didn't care much what anyone else thought. There are plenty of words both friends and foes would use to describe to Harvey: abrasive, curmudgeonly, stubborn, uncompromising. But those qualities were necessary just at the time Harvey arrived on the scene in Washington's history" ("What Harvey Manning Did for Wilderness").

Marc Bardsley, president of the North Cascades Conservation Council: "He was a guy who was able to see the big picture, figure out what the long-range approach should be, and then articulate his message in written form. It is unlikely that there will ever be another one like Harvey, able to use Shakespeare, the Classics, and his own wit to cut a pompous bureaucrat down to size" ("Remembering Harvey Manning").

Manning himself was much more modest when looking back over his accomplishments some years earlier: "The opportunity arises to be of some use, and so I take it, and we get things done, and that's the satisfaction" (The Seattle Times, May 23, 1991).

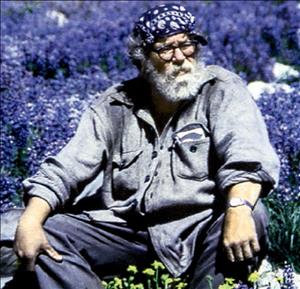

Manning left behind his wife of nearly 60 years, Betty; daughters Penelope, Claudia, and Rebecca; and son Harvey Paul Manning. A larger than life-size bronze statue of Harvey Manning, by Chimacum artist Sara Johani, stands near the Issaquah Trails Center. Showing a bearded, bespectacled Manning, hat askew, sitting on a rock contemplating nature, it is a fitting public acknowledgment of the immense contribution he made to preserving the Northwest's wild areas.