On December 12, 1911, voters in what is then Chehalis County (the Legislature will change the name to Grays Harbor County in 1915) overwhelmingly approve creation of the Port of Grays Harbor. The Port is the second in the state (after the Port of Seattle) to be created following passage of the Port District Act earlier in 1911. Over the next 11 years, the Grays Harbor port commissioners will work to establish a public port on the harbor, acquire land, develop a comprehensive plan, and overcome opposition to port development. Pier 1, the Port's first facility, will open in 1922 on the border between Aberdeen and Hoquiam, the county's two largest towns. The port commission will go on to develop more docks, establish Industrial Development Districts, dredge a deeper channel in the inner harbor to allow for larger ships, operate an airport and a marina, and collaborate on environmental rehabilitation projects. Though logs, lumber, and other forest products will dominate the Port's business, throughout its history it will work to diversify its business as a means to developing the region's economy.

Looking to the Future

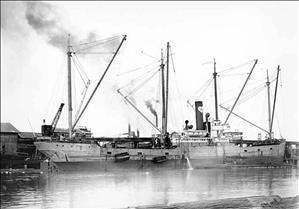

Port facilities on Grays Harbor in the early twentieth century consisted of docks built by mill companies alongside the bay; the Chehalis River; and its tributary, the Wishkah River. The mills were located on the shore because timber companies often rafted their logs down the rivers from the logging camps and because most of the lumber left the harbor via ships.

Large-scale harbor improvements, including dredging inner harbor channels, required a significant outlay of capital. No one business on the harbor could afford to undertake such large projects. Also, to a large extent, the existing harbor worked for the mill companies' shipping needs, so there was little impetus for developing the docks and freight-handling facilities that would bring new business to Grays Harbor.

Nevertheless, area businessmen looked to the future. The opening of the Panama Canal, though some time away, seemed to promise new business opportunities if the port was ready to handle the cargo. Grays Harbor was the only deep-water port on the Pacific north of San Francisco. Its location was one-half to one-and-one-half days closer to Asian ports than California or Puget Sound ports.

A number of other ports in the state faced similar challenges and opportunities and in March 1911 the Washington legislature passed the Port District Act. The act authorized the formation of public port districts that could develop port facilities and fund the projects with property taxes, bond issues, operating income, and other prescribed means.

Lamb Lobbies for a Port

One businessman who lobbied for the Port District Act, Frank H. Lamb (ca. 1875-1951), lived in Hoquiam. Lamb, a former timber company employee and owner of Lamb-Grays Harbor Company, which made machinery for pulp and paper mills, envisioned Grays Harbor's future as a diversified port handling all different kinds of cargo through numerous public docks and improved inner harbor channels. Just three months after the act's passage, area business owners organized an effort to create the Port of Grays Harbor in what was then called Chehalis County (the state Legislature changed the name to Grays Harbor County in 1915).

The County Commissioners agreed to put the measure before the voters in December. Proponents of the public port held meetings in each of the county's towns to convince voters to approve the measure. According to John C. Hughes and Ryan Teague Beckwith's history of Grays Harbor, Lamb played a central role in promoting the port. He wrote editorials and letters and spoke at community meetings. The arguments made in favor of the port district had little to do with the region's predominate industry, logging and timber. Instead, proponents emphasized the harbor's potential as a major port.

To voters in the eastern end of the county, with no waterfront and little industry, port supporters argued that the thriving metropolis that would grow up around a developed port would provide more markets for their farm produce, as well as increase land values.

Timber and mill companies, the largest landowners in the county, opposed the plan. In addition to opposing the taxes, they stood to gain less in the short term from public port facilities because they had already built their own docks on the waterfront and operated their own freight-handling equipment.

In the vote on December 12, 1911, voters approved the formation of the port in a 1,911 to 562 vote. Only Elma, a town in the east end of the county, returned a majority of votes against the measure.

Bogue's World-Class Plan

The voters also elected the unopposed port commissioner candidates. The port district encompassed the entire county, which was divided into three districts: Hoquiam, Aberdeen, and East County. Lamb was elected for the Hoquiam district and Angus McNeill (ca. 1865-1937), a real-estate agent in Montesano, was elected from the East County. William J. Patterson (b. 1872), a banker from Aberdeen, served as the first commissioner for the Aberdeen district. Although not openly opposed to the port during the election, Patterson proved to be a hindrance to port development while in office. Frank Lamb, in his memoir, explained how Patterson was supported by the timber companies and mill owners and served their interests while on the commission.

One of the Port District Act provisions required that port districts adopt a comprehensive plan before beginning any improvements. To that end, in 1912 the Grays Harbor commissioners hired Virgil G. Bogue (1846-1916), the preeminent civil engineer in the Northwest, to develop a plan.

Lamb described Bogue's plan as one that "would have served the port of New York -- at any rate it was 'comprehensive' enough to include anything we might want to do within the next hundred years" (Lamb, 236). Bogue divided the port into eight districts and listed the improvements needed for each. He arranged the different modes of port business according to their requirements: city business near the town centers; cargo facilities farther from town, but close to railroad lines; and industrial port facilities in open space farthest from town because of lower land costs and plentiful access to rail and water.

To remake the landscape to fulfill these functions, Bogue recommended relocating some bridges and the addition of others, removing shoals (mid-channel bars) from the riverbed, adding slips and bulkheads, filling tidelands, adding a railroad avenue in Hoquiam, and removing two bends in the Wishkah River. The truly comprehensive plan would fit the needs of a world-class port.

The commissioners approved the plan and sent it to the voters in December 1913. In a report they stated:

"Upon it depends the inauguration of measures for the systematic development of the Port and upon such development depends, [to] a large degree, the welfare of this county. Upon this measure also depends our preparation for the increase of commerce that will follow the opening of the Panama Canal [then under construction]" (Port of Grays Harbor Bulletin No. 1).

Newspaper articles supported the plan's adoption. The Aberdeen Daily World argued that "Aberdeen will depend on her general commerce in the future as on the lumber industry today" ("A Commercial Future"). The voters approved the plan on December 6, 1913, by a vote of 1,017 to 325.

Pier 1 at Cow Point

Earlier in 1913 the state legislature deeded 68.744 acres to the Port. Located on the waterfront between Hoquiam and Aberdeen, the land's location prevented any squabbling over which town would benefit more from future improvements.

After a bit of political maneuvering, a new commissioner, Joseph Vance (1872-1948), from Malone, was elected for the East County district in 1919. Vance worked with Lamb, Patterson dropped his resistance, and Port projects began to move forward.

In March 1920 the Port hired Charles A. Strong (ca. 1884-1947), a civil engineer from Tacoma, to develop a five-year plan for carrying out Port projects. Presented at the end of the month, the plan called for construction of a dock at Cow Point, on the land from the state, and a dredging program for the inner harbor and river. Voters approved the sale of bonds and work commenced.

The dock at Cow Point, known as Pier 1, opened on September 22, 1922. It featured a 2000-foot by 300-foot dock with a slip alongside. A warehouse on the dock could hold twenty million board feet of lumber. A five-ton traveling crane and other freight-handling equipment could load cargo to and from ships. At the opening ceremony two Suzuki Line steamships were being loaded as dignitaries made their speeches.

To maintain equity in the location of Port facilities, the Cow Point dock had been built astride the end of the street dividing Hoquiam and Aberdeen. Hoquiam city officials hosted the ceremonies in September celebrating the first outbound cargo and Aberdeen officials hosted festivities in October celebrating the first inbound cargo. Grays Harbor residents quickly saw a return on their investment when the Trans-Marine Corporation announced that it would begin direct shipments to Grays Harbor instead of sending cargo through San Francisco.

Prodigious Growth

The 1920s brought prodigious growth in exports from Grays Harbor. A combination of factors drove worldwide demand for Grays Harbor lumber. After a slow start, the Panama Canal began to realize its potential in the 1920s. In 1922 an earthquake in Tokyo and the fires that followed it destroyed homes and buildings. Japan turned to Grays Harbor for much of the lumber it needed to rebuild.

Lumber exports grew enormously each year. On December 21, 1924, the Port celebrated shipping its billionth board foot in that year. Exports surpassed a billion feet annually for the next several years, making Grays Harbor the largest lumber-exporting port in the world.

The Great Depression abruptly ended the lumber boom. As tax revenues declined in the 1930s, the Port struggled to maintain its facilities and continue dredging operations. The federal government took over dredging operations and funding from the Civil Works Administration and the State Emergency Relief Agency funded repairs to the Port's wooden docks.

Airport and Marina

In 1941, the federal government funded an airport at Grays Harbor that would eventually become a Port property. The Moon Island Airport was built as part of a civil-defense system as a military airport in case of an attack on the air field at McChord Army Air Base (now Joint Base Lewis-McChord). In 1953, in honor of Robert Bowerman's military service and his work at the Moon Island Airport, the airport was renamed Bowerman Field Airport. In 1962 the Port of Grays Harbor took over ownership of the airport from Grays Harbor County.

After the war, the Port began upgrading its marina in Westport, which it had run since 1928. In the 1950s commercial and sport salmon fishery vessels filled the marina to capacity. During the 1960s and the 1980s the Port carried out modernization projects: The salmon fishery continues to attract visitors today.

In the face of declining salmon runs, the Port helped establish the Grays Harbor Fisheries Enhancement Task Force (now the Chehalis Basin Fisheries Task Force) in 1980. The task force, a coalition of government agencies, tribal governments, industry, and fishing groups, seeks to improve salmon and steelhead habitat in the Chehalis River basin and increase fish populations through hatcheries.

Lumber exports fueled the economy of Grays Harbor and provided the bulk of the Port's business into the 1980s. The Columbus Day Storm on October 1962 struck the West Coast with hurricane-force winds. The winds took down 17 billion board feet of timber, much of it on the Olympic Peninsula. When the salvage operations brought in more logs than area mills could cut, the state awarded a salvage contract to a Japanese company, which then exported the logs, providing considerable business for the Port of Grays Harbor.

Industrial Development

Decades of logging in the region's forests and federal court rulings restricting logging in areas inhabited by the threatened northern spotted owl led to a dramatic reduction in logging and lumber in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Henry Soike (b. 1921), general manager of the Port from 1974 to 1988, led the Port in its efforts to diversify its business. Utilizing Industrial Development Districts that were established in the 1960s, the Port has been able to lease land to companies that locate their businesses in Grays Harbor. A retail development anchored by Wal-Mart is located on Port land. On the landward side of Terminal 1, Imperium Grays Harbor operates a biodiesel plant.

Soike's adroit lobbying gained federal funding for the Deeper Draft Project, a dredging project that deepened the inner harbor channels to accommodate ever-larger oceangoing vessels. Likewise, a decades-long working relationship between the Port and the railroads has kept a rail connection in Grays Harbor. The current railroad, the Puget Sound and Pacific Railroad, operates the only rail line to the coast north of San Francisco. It connects with the Burlington Northern Santa Fe and the Union Pacific lines near Chehalis. The dredging project and the rail connection have made it possible in recent years to gain a bulk handling facility, developed by AG Processing, at Terminal 2, and a new auto export operation run by The Pasha Group, which handled one-third of the West Coast's auto exports in 2011. Additionally, DKoram, Inc. began handling log exports through the port in late 2009, taking the logs to expanding markets in China and South Korea.

A piling upgrade at the Westport marina, completed in 2010, allows that facility to handle larger craft. According to Jack Thompson, Port of Grays Harbor Commission President, the new pilings will "improve our ability to handle the larger fishing vessels becoming prevalent in today's market" (Thompson). The port replaced ten wooden pilings with galvanized steel pilings that are stronger and longer-lasting. The marina handles more than half of Washington's commercial fish and crab landings, making it the largest fishing port (by volume handled) in Washington and seventh in the nation.

In 2011 the Port's auto and soy meal exports, biodiesel production, light industry, airport, and marina are a far cry from the lumber-based economy of the early years. Grays Harbor is on its way to creating the world-class port its founders envisioned.