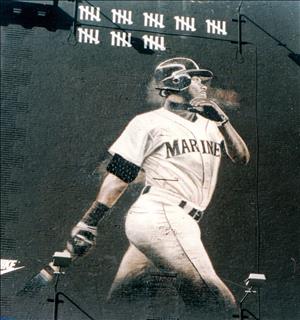

On June 2, 2010, with a surprise announcement just a few hours before a game, Ken Griffey Jr. (b. 1969) retires from baseball, ending the most accomplished and celebrated career in Seattle Mariners history. He leaves at age 40 with almost legendary status. In 22 seasons, he hit 630 home runs, the fifth-most in Major League Baseball history. In his prime he was also an outstanding centerfielder, as renowned for making difficult, clutch catches as for hitting dramatically timed home runs. His retirement is not totally unexpected -- he had lost his job as an every-day designated hitter – but its suddenness is a jolt to his teammates and to fans who remember him as Seattle’s best and most beloved player.

The Kid

He was called The Kid for good reason. His father, Ken Griffey Sr. (b. 1950), was an established star in the National League. Junior grew up in the clubhouse of his dad’s team, the powerful Cincinnati Reds. By the time he was a senior at Cincinnati’s Moeller High School, he was attracting hordes of major-league scouts. The Mariners had first crack at him because they had baseball’s worst record the previous season. He was only 17 when they made him the first pick in the 1987 amateur draft.

After two short minor-league seasons in Bellingham, Griffey Jr. made the big-league roster in 1989 by leading the team in hitting during spring training. The 19-year-old announced his arrival to the big time in what would become typical fashion for him, delivering big hits on special occasions. In his first at-bat, he pounded a double off the outfield wall in Oakland. In his first Kingdome at-bat, he hit a home run.

From the start and throughout his career, he radiated joy as a player. He wore his hat backwards during batting practice. He clowned with teammates and teased media members. He was a perpetual prankster. In one classic instance, he paid off a bet for a steak dinner with manager Lou Piniella by having a cow delivered to Piniella’s office. Off the field and on, he flashed a wide smile that became one of his trademarks, along with a picture-perfect swing.

Griffey gave the city plenty to remember. He and Griffey Sr. made history in August 1990 as the first father-son tandem to play on the same Major League team, and again two weeks later, when they hit back-to-back home runs. He was selected for 13 All-Star Games, including 1992 when he was named Most Valuable Player. He tied a Major League record in 1993 by hitting home runs in eight consecutive games. He was named the American League’s Most Valuable Player in 1997, the first of two straight seasons when he hit 56 home runs. And he won 10 consecutive Gold Glove awards for being the best defensive player at his position.

That Magic Season

The year that shined biggest for Seattle fans was 1995. The Mariners had never won their division and had only two winning seasons since the birth of the franchise in 1977, and they were having another moribund year. In late May, Griffey broke a wrist crashing into the Kingdome outfield wall after making a spectacular catch and missed 73 games because of the injury. The Mariners were a seemingly insurmountable 12-1/2 games behind the division-leading California Angels on August 24 when Griffey ignited an improbable team turnaround. With two outs in the ninth inning of a tied game against the New York Yankees, he hit a two-run home run. That started a three-game sweep of the Yankees and a six-week period that made baseball a big deal in Seattle for the first time.

The Mariners finished the season tied with the Angels, forcing a one-game playoff for the division championship. They won the title with a 9-1 victory in a packed Kingdome amid deafening cheers. From there they beat the heavily favored New York Yankees in the five-game divisional playoffs. The final play burns bright in the memories of a generation of fans. The Yankees were leading 5-4 in the bottom of the 11th inning when Griffey scored all the way from first base on an Edgar Martinez hit. The Kingdome nearly exploded as fans and players celebrated. Photographers caught the moment, the image of Griffey and his mile-wide smile at the bottom of a pile of jubilant Mariners. The victory put them in the American League Championship Series. Although they didn’t win that series, they did win a longer run in Seattle.

The House Griffey Built

The owners of the team had been pushing for a new stadium since 1992, and finding little support from politicians or the public. In 1995, the state legislature proposed raising the sales tax in King County to fund a $240 million ballpark with a retractable roof, but the legislation required voter approval. Voters rejected it by fewer than 1,000 votes on September 19, 1995, increasing speculation that the team might relocate to Tampa, Florida. But as the Mariners stormed toward the playoffs in the season’s final weeks, Kingdome attendance soared and regional interest in the team reached unprecedented heights. After much wrangling, the political will to build a new stadium was found, this time by-passing the voters. Safeco Field opened in July 1999 to rave reviews and record attendance.

When Griffey announced his retirement, attention was paid specifically to 1995 and the stretch run that changed everything for Seattle baseball. The team that turned it around had plenty of talent, notably Martinez, Jay Buhner, Alex Rodriguez, and dominating pitcher Randy Johnson, but Griffey was their brightest star and their leader. "They say in New York that Yankee Stadium is the house that Ruth built," Team President Chuck Armstrong said. "In Seattle, Washington, we say that Safeco Field is the house that Ken Griffey Jr. built" (Condotta, The Seattle Times).

Griffey was traded at his request after the 1999 season because he wanted to be closer to his family in central Florida. He spent eight-plus seasons with the Cincinnati Reds and a short time with the Chicago White Sox. When he returned to Seattle in 2009, he brought back some of his old magic. Although his batting average was only .214 that season, he hit 19 home runs and was widely credited with helping to create a harmonious clubhouse atmosphere that led to another major turnaround. After losing 101 games the previous year, the Mariners won 88. When the season ended, Griffey’s teammates carried him around the field on their shoulders.

Curtain Call

In a perfect baseball story, he would have retired then. But he returned for another curtain call in 2010 and the magic was gone. When he decided to call it quits he was hitting only .184 -- 100 points below his career average. After 98 at-bats, he had no home runs and only seven runs batted in. Worse yet, he was all but irrelevant as a player and had been humiliated by a story in the Tacoma News Tribune that said he was asleep during a game.

That was forgotten as soon he announced he was leaving. The word came in the form of a written statement. It said, "While I feel I am still able to make a contribution on the field, and nobody in the Mariners front office has asked me to retire, I told the Mariners when I met with them before the 2009 season and was invited back, that I will never allow myself to become a distraction. I feel that without enough occasional starts to be sharper coming off the bench, my continued presence as a player would be an unfair distraction to my teammates, and their success as a team is what the ultimate goal should be" (Condotta, The Seattle Times).

By the time that was delivered, Griffey was gone. In fact, he was driving alone toward his home in Orlando when the team learned of his decision. Word was quickly forwarded to the media. The grounds crew hastily crafted a large version of his number 24 in the infield dirt behind second base. Before the first pitch, a five-minute video of his career highlights was shown on the Safeco Field scoreboard screen while the crowd stood and cheered. Some cried. The consensus of opinion was that he would be a first-round addition to the Baseball Hall of Fame as soon as he is eligible, in 2016. Also expected was a scripted retirement ceremony later in the season and a position for him somewhere in the Mariners organization.

Beyond that, there was discussion among fans and media members about whether he was the top athlete in Seattle history. Longtime sports writers Art Thiel and Steve Rudman and radio host Mike Gastineau already had maintained that he was. The final entry in their 2009 book, The Great Book of Seattle Sports Lists, ranked the 100 best athletes in state history. Thiel wrote in a column for seattlepi.com that his co-authors "debated ruthlessly with me from No. 100 down to No. 2. No. 1 required no discussion."

He then quoted from the book: "Not merely because of the 398 home runs (as a Mariner), or the numerous spectacular catches, Griffey was the Mariners’ first big gate attraction, first superstar, first annual All-Star starter, most forceful personality and the biggest reason the franchise was able to escape its dubious history to become a Northwest summer-entertainment fixture and one of the most successful business operations in pro sports" (Thiel, seattlepi.com).