The town of La Center lies on the north bank of the East Fork of the Lewis River in northwest Clark County, some 16 miles north of the county seat at Vancouver. Cowlitz Indians inhabited a broad range from as far north as present-day Mossyrock to within a few miles of the Columbia to the south, but were largely displaced by white settlers. Early La Center served as the hub of commerce for Lewis River trade and benefited from the booming lumber industry. Depletion of the forests and the lack of other industries led to a long period of decline, in the 1980s bringing the town to the edge of bankruptcy. A decision to allow card-room gambling, subject to a hefty 10 percent tax, provided desperately needed revenue. After years of little or no progress, the population ballooned from less than 500 in 1990 to more than 2,500 in 2010. The town now (2010) has ambitious plans for further development, but these may depend in part on the outcome of an ongoing dispute with the Cowlitz Tribe over the tribe's plans to build a huge casino complex adjacent to Interstate 5 on the outskirts of La Center.

The Lewis Cowlitz People

The East Fork has its source in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, flows through Clark County past La Center, and empties into the main Lewis River just below the town of Woodland. The Lewis River was called the Cathlapotle by the Chinook Indians, whose main village was near its mouth at the Columbia River. However, the Cowlitz were the aboriginal inhabitants of the area.

The Cowlitz Indians were a widely dispersed tribe that lived in small groups scattered through the interior what are now Cowlitz, Lewis, and northern Clark counties. The tribe had two major divisions, the Upper and the Lower Cowlitz. Although they often shared the same territory and followed similar customs, the Upper Cowlitz intermarried with Sahaptan-speaking Indians from east of the Cascades and eventually adopted their language, whereas the Lower Cowlitz retained the tribe's traditional Salishan tongue. A subgroup of the Lower Cowlitz lived in villages on the Lewis River and became known as the "Lewis Cowlitz"; during the nineteenth century they were often misidentified as Klickitat.

The word "Cowlitz" is believed to mean "capturing the medicine spirit," a reference to a rite of passage in which young men would remove themselves to sacred points along the Cowlitz River on fasting treks, communing with the spirit world. Some sources hold that Lewis and Clark "discovered" Cowlitz at Fort Clatsop in 1805, but others disagree, and it appears unlikely. The Columbia River shoreline was dominated by the Chinooks, who did not always get on particularly well with the Cowlitz. The first well-recorded contact between the tribe and Westerners came in 1811, when Astorians from the Pacific Fur Company ventured up the Cowlitz River from its junction with the Columbia and had a peaceable meeting with dozens of Cowlitz traveling the river in canoes. A later, and much less happy, encounter occurred in 1818, when a group of Iroquois Indians employed by the North West Company assaulted several Cowlitz women. The offended tribe killed one Iroquois and wounded two others, and the Iroquois retaliated by attacking a nearby Cowlitz village, killing about a dozen.

Although they were inland, the Cowlitz did not escape the epidemic of "intermittent fever" that began ravaging coastal tribes in 1829, a pestilence that is believed to have been imported on an American ship, the Owyhee. By the time the disease burned itself out in the early 1840s, it had decimated the Native American population of southwestern Washington. The total Cowlitz population in 1800 was estimated at 80,000; by 1860, the estimates of the surviving Lower Cowlitz ranged from 150 to 350.

The Cowlitz who lived in the vicinity of present-day La Center when the first white settlers arrived were by all accounts non-threatening, despite two unsuccessful attempts in the early 1850s to negotiate a reservation treaty with the U.S. government. The Cowlitz largely stayed out of the Indian Wars of 1855-1856, although the Klickitat, with whom the Lower Cowlitz had extensively intermarried, took part. But their peaceful intentions were not taken at face value -- many members of the tribe sat out the war in detention camps, pacified by the promise of finally getting an acceptable reservation once hostilities ended. And a Cowlitz chief, Umtux, was killed under mysterious circumstances in November 1855 while leading some of his people away from detention at Fort Vancouver due to fears that they were about to be attacked by frightened white settlers. Umtux's death was the only casualty, and in fact the only violence, in the "battle" that led to the naming of the town of Battle Ground.

This promise of a reservation for the Cowlitz was not to be fulfilled for several lifetimes. In fact, just the opposite occurred. In 1863, an Executive Order opened Cowlitz land to white settlement, and over the ensuing years the remaining Cowlitz became further scattered throughout southwest Washington and northern Oregon. The gradual dispossession of the tribe continued into the twentieth century, as roads and eventually railroads opened the interior to ever-greater numbers of white settlers. In a true Catch-22, the federal government adopted the position that since the tribe was now landless, it could no longer even be considered a tribe.

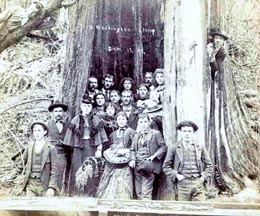

Late in his life, Chief Atwin Stockam, who was over 100 years old when he died in 1912, sadly and succinctly summed up the history of his tribe since the arrival of the settlers:

"Long ago all this land belonged to lndians — salmon in the chuck [river], mowich [deer] and moollok [elk] in the hills. Then white men come. Atwin their friend. Now all this land belong to white man" ("The Dispossessed: The Cowlitz Indians in Cowlitz Corridor").

Throughout the last half of the nineteenth century and most of the twentieth, the Cowlitz tried to maintain a tribal identity and obtain official recognition, a task made more difficult by several circumstances. First, the Upper and Lower Cowlitz did not even speak the same language, a fact that weighed heavily against the idea of a unified tribe. Also, the Lower Cowlitz, in particular, had freely intermarried with several other tribes, most prominently the Klickitats, and their individual identity to some extent had become subsumed into larger and more cohesive groups. And finally, a significant number of surviving Cowlitz were "Metis," descendants of children born of marriages between Cowlitz women and French-Canadian trappers. There were enough Metis to form Meti societies, often French-speaking and Roman Catholic, that lived apart from other Cowlitz, and this further complicated the battle for recognition.

Chief Atwin Stockam sued the federal government in 1906, seeking to recover several pieces of land for his tribe, and this was the opening shot of a series of legal battles that ebbed and flowed for nearly the next 100 years. Throughout the twentieth century, the Cowlitz carried on a lonely battle for recognition, always opposed by bureaucrats and sometimes opposed by recognized tribes that feared a Cowlitz gain might be their loss. Finally, after decades of struggle, in January 2002 the Cowlitz, now 2,400 strong, were granted full recognition as a tribe, and they set about putting together a reservation.

The First Settlers

The 1850 the passage of the federal Donation Land Claims Act spurred a tidal wave of settlement across the western United States. The first non-Natives to put down permanent roots in the La Center area were John H. Timmen and Aurelius Wilkins, who in 1852 laid claims to land about five miles up the East Fork (some early histories refer to it as the "South Fork") of the Lewis River from the present townsite. John Pollock, who with his brother staked a claim on the south bank of the Lewis, arrived later that same year. These trailblazers worked clearing the land and tilling the soil, and soon a growing but scattered agricultural community was in place.

There does not appear to have been a major concentration of Cowlitz Indians in the area when the settlers arrived, but those who were there coexisted peacefully with the newcomers. However, when the Indian wars erupted in 1855, the white people living in their isolated homesteads were panicked by reports of coming attacks by "renegade" Natives. Women and children were rounded up and taken down the Lewis River to the Columbia, where they crossed to Oregon and took shelter in the St. Helens blockhouse. The men who stayed behind formed the Lewis River Rangers, a 44-man volunteer "army" that did not meet with the approval of the regular U.S. Army, stationed at Fort Vancouver to the south. But hostilities did not break out along the Lewis River, the Indian uprising was soon quelled, women and children returned, and the farmer-soldiers put down their arms and returned to work.

A Center of Commerce

For most of the 1800s, rivers were the primary means to travel into the interior of Western Washington, and it didn't take long after settlement began for commercial vessels to penetrate the lower reaches of the East Fork of the Lewis. In the early days, river traffic consisted of bringing people and supplies into the area and shipping agricultural products out. The boats, all steam-powered sternwheelers, ranged as far east as Stoughton's Landing, a few miles upriver from the future site of La Center. In the summer when the water was low, smaller vessels called lighters would ferry goods and people upriver from wherever the larger ships were forced to stop.

Some sources say that the first steamship to arrive in the vicinity of what would become La Center was the Eagle, in 1854, but others put the date as late as 1868. It is certain, however, that by 1870 there was regular scheduled commerce on the East Fork. In that year the Swallow, a 45-foot steam-powered sternwheeler, started running up and down the river, stopping at each scattered homestead to trade "dry goods and groceries for cash, butter, eggs and honey" ("Steamboat Era on Lewis River, 1854-1920"). The Swallow's career on the river came to an unhappy end in 1874, when she was capsized and sunk by a floating snag. Other sternwheelers making the East Fork run in those early days were the Mascot and the Walker.

For reasons that are no longer apparent, the site of present-day La Center was first known as "Podunk," a name that may not then have had the negative connotations that it has today. One of the original upriver settlers, John Timmen, is credited with founding the town that is now La Center in 1871. It is also not clear just exactly what Timmen did to earn the credit as town founder, as it was a well-known riverboat captain, William G. Weir (1834-1902), who a year later built the first house there and opened its first store and post office. In any event, it was Timmen who, on December 6, 1874 (at least one source says 1875), filed the town's first plat, and wisely changed its name from Podunk to Timmen's Landing. Another small mystery is when the name "La Center" or "LaCenter" was first adopted: Some sources say that it was within a few years of the original plat; others hold that the name change did not occur until the town was formally incorporated in 1909. What is undisputed is that the name was intended to convey, albeit in a mixture of French and English, the town's role as the center of commerce for northern Clark County.

In 1874 the economy of La Center was almost entirely agricultural, and Timmen donated land to H. M. Knapp, a Deputy Grand Master of the Masonic "Patrons of Husbandry," for a local Grange. Knapp built a two-story structure to house the organization, reputed to be the first grange in Washington Territory.

Taking the Forests

For the first few years of its existence, La Center was by all accounts a very quiet place, peopled mostly by farmers, dairymen, and a very few tradesmen. It was not long, however, until the potential of the area's vast timber resource was realized, and logging became the area's first real industry.

In 1876, Joseph D. Banzer (1837-1902) and a partner who is identified only as "Titus" started the area's first commercial logging operation, using oxen, Cayuse ponies, and horses to haul logs to their mill or to the river to be floated downstream to the Columbia and on to Vancouver and Portland. The company was credited with putting 700,000 feet of logs into the East Fork, although the record does not indicate the time period in which this occurred.

Despite its relative isolation, some growth took place. A woman named Mary Brazee Fairhurst added to the town plat in 1884, and the following year it would be reported that La Center, in addition to its farms and mills, had two hotels, a Methodist church, a grist mill, a brickyard, and a post of the Grand American Army of the Republic, a fraternal organization for Union veterans of the Civil War. A devastating fire destroyed the town's wharves and warehouses in 1890, but they were soon rebuilt and the small settlement continued to prosper.

The New Century

The historical record for La Center is quite sparse for the last decades of the nineteenth century, but it is clear that logging, lumber mills, dairies, and farming were what sustained the area's small population. A state government report from 1907 noted:

"LaCenter is a considerable town with a population of about 300. A prosperous dairying and mixed farming surrounds the place, while lumbering and logging are extensively carried on in the vicinity. Eight sawmills employing an average of forty men each are located within a radius of five miles of LaCenter and other are projected. Railroad ties in vast quantities are turned out at these mills. LaCenter has water communication with the outside world and also has stage connection with the Northern Pacific railroad at Ridgefield" (A Review of the Resources and Industries of Washington: 1907).

The foregoing passage illustrates both La Center's strengths and its weaknesses in the first decade of the twentieth century. Its mills may have provided hundreds of jobs to men who turned out tens of thousands of railroad ties for the new lines that were linking Northwest towns to each other and to the rest of America, but the railroad itself did not come to La Center. The nearest railroad access was at Ridgefield, which was only 10 miles distant, but those were 10 miles of bad road, incapable of handling commercial traffic of any significance.

But for the time being, La Center continued to prosper in a low-key way. The Coast magazine briefly profiled the town in its April 1909 issue, and its inventory of the town's businesses showed that progress had been made since the 1907 state report:

"Within a radius of seven miles around La Center there are at present about twelve sawmills engaged in cutting lumber and ties. These mills employ from forty to sixty men each ... . Our business houses consist of four general stores, one drug store, two hotels, one restaurant, one livery stable, two blacksmith shops, one saloon, one hospital, one furniture store and one pool room" (The Coast).

But even this boosterish article contained bad news for the future of the town:

"A few years ago, north of La Center lay one of the finest forests of red and yellow fir that one would wish to see. Since that time about one-half of this forest has been marketed, and the logged-off lands are used for grazing and general farming" (The Coast).

Forests were a finite resource, one that the intensive logging around La Center was rapidly depleting. It was this logging and the mills it fed that had supported many of the town's other commercial activities, and the end of the jobs and income derived from the timber industry was on the horizon. The day was not far off when La Center would once again have to place more reliance on agriculture than on industry.

A Sleepy Town

In 1909, the voters of La Center decided to incorporate their town, and incorporated status was granted on August 27, 1909. One immediate effect of this was that the town was included in the 1910 federal census, and all censuses that followed. During the twentieth century, La Center remained a sleepy rural town.

The 13th Federal Census of 1910 showed stunning growth across almost all of Washington state, with the population expanding by more than 620,000, easily doubling since the previous census of 1900. And although this explosive growth slowed considerably in later decades, the state's overall population continued to expand, but La Center's did not. In 1910, the population of La Center was 288, a figure that it was not to reach again until 60 years later. By 1920, the town had only 167 residents; by 1930 it had rebounded slightly, to 219. But 1940 showed another decline, to 193, and 1950 was only slightly better, with 204 residents. Between 1910 and 1950 the population of Clark County more than tripled, from approximately 26,000 to over 85,000. In that same period, the population of La Center dropped by more than 40 percent.

The tiny town had bucolic charm and peaceful country living. Yet it did not have the industrial or commercial base to support population growth. Even the routing of the original State Route 1/Pacific Highway through La Center in 1918 didn't seem to help -- thousands of newly mobile travelers passed by, but few lingered.

Gambling on the Future

During the second half of the twentieth century the little town did grow. By 1970, La Center had 300 residents, the most since counts were started 60 years earlier, and by 1990, 483 people called it home. But despite the modest increase in population, in the 1980s La Center was in dire financial straits. A moratorium on new construction was imposed due to the inadequacy of the town's sewage plant, and the wells that provided water were running dry. Given the lack of commercial activity, and the small number of residences, the tax base was insufficient to fund basic town services. Facing bankruptcy, in 1985 La Center became the only town in Clark County to license card-room gambling, and imposed a 10 percent tax on the activity. This step was not supported by everyone, but there is no doubt that it saved the town from financial ruin.

The revenues from the gambling tax breathed new life into La Center. Clark County also stepped in to help, taking over the town's water and sewage treatment facilities. Roads were repaired, and money became available to extend town services to new developments. By 2002, nearly 75 percent of the town's revenues came from the gambling tax ($3,176,413). Of more importance, these revenues allowed La Center to break out of its long slumber and attract new residents, and with them, new businesses. In recent years the town has been able to lower the gambling tax as other streams of revenue have increased.

The effect of the gambling tax on the growth of La Center has been dramatic. Without that revenue, the town may not have survived. Instead, growth exploded during the 1990s. New housing developments were built, including Southview Heights, which opened in 1995 and drew many new residents to the area, most of whom commute to work in the nearby commercial centers of Vancouver and Portland. Between 1990 and 2000, the population of La Center ballooned from 483 to 1,654 residents, or by nearly 250 percent. By April 1910, that number had increased to more than 2,500. Freed from the constraints of poverty, the city now hopes to secure its future by annexing approximately 1,675 acres from its urban growth area, a huge increase over the current 650 acres.

The Return of the Cowlitz

Given the dispossession of the Cowlitz Indians that took place over 100 years ago, it is ironic that the tribe is now perceived by many to pose the greatest threat to La Center's longterm economic health. Although new population and commercial activity has served to broaden the town's tax base, gambling-tax revenue is still crucial to its economic well-being, and the Cowlitz Tribe's plans to provide money and jobs for its 3,000 enrolled members have put it into conflict with the town.

Having fought for decades for tribal recognition, the Cowlitz are engaged in a new and protracted battle, this time over its proposal to create an "initial reservation" and develop a $500 million casino on 152 acres of land that it owns adjacent to Interstate 5 on the outskirts of La Center ("Cowlitz Casino Resort"). Among the town's primary concerns are the effect the project would have on its own gambling revenues, and on its roads and schools. So far, all attempts at compromise have failed. The final Environmental Impact Statement for the tribe's proposal was issued on May 30, 2008, but no final decision on the fate of the project has yet (June 2010) been reached.

There are persuasive arguments on both sides of the Cowlitz Casino controversy, and historical truths that weigh heavily on the relationship between the tribe and its neighbors. But whatever happens, the little town of La Center has endured decades of adversity, and in more recent years has brought itself back from the brink of ruin. Regardless of the outcome of the current dispute, there is every reason to think that La Center will continue to grow and prosper in future years.