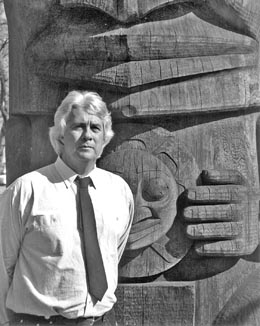

One of perhaps 100 Native American architects in the United States, architect Johnpaul Jones has manifested his Choctaw/Cherokee heritage in the creation of an internationally significant legacy of projects that honor the land and cultural heritage. Beginning in the 1970s, Jones's work in architecture, as a founding principal of Seattle-based Jones & Jones Architects and Landscape Architects, helped alter the direction of zoological design: innovative projects at Seattle's Woodland Park Zoo earned widespread recognition for innovation in providing healthy environments for captive animals and heightening human sensitivity to cultural and environmental issues. Jones has led the design of numerous cultural centers and museums with tribal organizations spanning the North American continent, culminating in his 12-year engagement as lead design consultant for the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian (completed 2004) on the Capitol Mall in Washington, D.C. More recently he designed Vancouver Land Bridge (2009) as part of the Confluence Project directed by renowned environmental artist Maya Lin (b. 1959). In action as well as by example, Jones has also worked effectively to encourage individuals from American Indian and other backgrounds toward success in the design professions.

Growing Up in Oklahoma and California

Johnpaul Jones was born in Okmulgee, Oklahoma on July 24, 1941, to Wales-born father Johnpaul Jones and his wife Dolores, daughter of a Choctaw/Cherokee mother and a Choctaw father. Johnpaul spent his early years in the family's tenant farmhouse on the outskirts of the town of Okmulgee, the capital of the Creek Nation since the Civil War. “In those days Indians couldn't live in town, and neither could blacks. And we didn't have reservations, so we lived in a segregated 'area'" (Jones/Rose Hancock conversation). Neither parent had gotten past the sixth grade. Johnpaul Sr. worked as a butcher to support the family, which grew to include Jones's five younger sisters. Their grandmother, Pearl Gurley, lived nearby, and instructed the family in the Indian ways.

Their father left the family about 1950, and their mother took advantage of an Indian relocation program to move the family to Manteca, California, where she and the children did field work. Johnpaul Sr. returned briefly and moved with the family to Stockton, then the parents divorced and teenager Johnpaul and three of his sisters moved with their father to Los Gatos, California. Jones attended middle and high school there, graduating in 1959. Though a "bad boy" and "dyslexic," Jones took all the art classes he could, and always did well. "They put me in shop classes, where I always did well with mechanical drawings" (Jones/Rose Hancock conversation). He also excelled in athletics, particularly swimming and water polo.

In California, the Jones family had no connection with other Indians, but instead “mostly Hispanics. All our schoolteachers were white." Twice a year, their mother would drive the children back to Oklahoma to visit family and to attend the mid-summer “stomps." Jones had no grand plans for his future: "I'd either go into the military or get some kind of job, and my sisters would get married and have children" (Jones/Rose Hancock conversation).

Following his 1959 graduation from high school, Jones studied at San Jose City College. He heard of an office-boy job opening at the Higgins & Root architecture firm in San Jose, and showed up at the office one morning ready to apply. He waited all day, looking through the window with fascination at the drafters at their work stations "until Chester Root showed up at 4 p.m.. Since I'd waited so patiently, I got the job." Jones recalls that "Chester Root and Bill Higgins took me under their wings, and let me job-shadow them" (Jones/Rose Hancock conversation). Based on his drawing skills, Jones soon advanced from office-boy work. At the same time, he attended San Jose City College.

Education in Architecture

With growing confidence, Jones determined to take advantage of a water-polo scholarship and attend the University of California. He applied to Berkeley, but didn't pass the foreign language entry requirement. "I probably would have flunked out anyway, as I was not prepared for serious college studies." One of the architects at the firm recommended the University of Oregon and its architecture school, and the firm bought Johnpaul a plane ticket "on a United Airlines flight that took off from San Francisco and landed at Redding, Roseburg, and Eugene." Jones "walked around the campus by myself:

"I didn't talk to anybody; I just visited classes and the art school, and decided I wanted to go there. I took my transcript to the admissions office, and they offered to have me come there in the summer for an audition. I passed, and started the five-year architecture program" (Jones/Rose Hancock conversation).

Chester Root transferred the University of California scholarship to Oregon for two years, to assist Jones. "Chester Root said I should pass along to others any good that came to me" (Jones/Rose Hancock conversation).

Jones recalls a broad course of studies that exposed him not only to the basics of architecture but to landscape architecture, urban design, and interior design, with influential teachers including Julio San Jose (later Dean of the New York Institute of Technology School of Architecture: "He made me think") and Donlyn Lyndon (b. 1931, later Dean at UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design). Jones also recalls studying architectural history with Marion Dean Ross (1913-1991), "but though the books we read mentioned Native architecture, our teachers never said anything about that. I read a lot of Sir Banister Fletcher's work on American architectural history, and wished I could write a history of Native American architecture" (Jones/Rose Hancock conversation). Fletcher (1886-1953) was the author of A History of Architecture.

During his school years at Oregon, Jones returned to San Jose in the summers to work at Higgins & Root.

Marriage and Early Career

Jones met and married Hannah Stratton, an art student at Oregon, in 1965, and their family grew to include children Sequoiah (later a firefighter on Bainbridge Island) and Ingrid, who became a librarian. (The marriage ended in 1990.) In 1967, Jones graduated with the Bachelor of Architecture degree, and not long after set out to hitchhike to British Columbia. As he passed through Seattle, a friend from Oregon urged him to apply for a job with Paul Thiry (1904-1993), a distinguished architect noted for his work as principal architect of the Seattle World's Fair of 1962. Jones got the job, and went to work in Thiry's office on Madison Street, near the offices of other notable architects of the day: A. O. "Al" Bumgardner (1923-1987), Fred Bassetti (1917-2013), and the firm of Naramore Bain Brady & Johanson (now NBBJ).

As Jones recollects, "Thiry really worked on the cheap, he paid beans, he didn't heat the office, and he was always grumpy -- but he produced phenomenally creative designs." Jones did work “on both sides of the office, design and construction documentation. I really learned a lot" during the years at Thiry's firm (Jones/Rose Hancock conversation). In 1968, Jones went to work with the Seattle firm of Dersham & Dimmick for a couple of years, before opening his own office on Bainbridge Island.

“Professionally, Jones struggled at first in Seattle. At one point he paid medical bills for his first wife ... with sketches he had made of ferryboats sitting in the Eagle Harbor maintenance yard on Bainbridge Island" (Newnham). Jones also provided drawing and design services to Swedish Hospital to pay off the debt incurred. Through this work he first came into contact with the American Indian Women's Service League, and began work with the Urban Indian Committee. In this connection he met Bernie Whitebear (1937-2000) and others involved in local Native American advocacy.

In the early 1970s, Jones learned of the Harvard studies by Grant Jones on the then-little-known Indian burial mounds located in the Midwest. This introduction led to Johnpaul Jones's joining Grant Jones and Ilze Jones (none of the three are related) as founding partners in the Jones & Jones firm in Seattle, blending professional backgrounds in architecture and landscape architecture. Beginning early in the partnership, Jones & Jones Architects and Landscape Architects located its offices in the historic Globe Building in Seattle's Pioneer Square.

Natural Environments for Captive Animals

In their early work, Jones & Jones's design of exhibits at Seattle's Woodland Park Zoo pioneered the movement to create more natural environments for captive animals and to help educate the public about the animal and natural world. A December 1987 article in The Atlantic highlighted the firm's work on the Woodland Park Zoo's gorilla habitat, led by partner Grant Jones in association with biologist Dennis Paulson and Zoo director David Hancocks, as evidence that "A revolution is under way in zoo design."

The article recounts that Dian Fossey (1932-1985), a scientist who lived near and studied wild gorillas in Rwanda, flew to Seattle to consult with the designers. Later she wrote back that she had shown photos of the completed exhibit to her colleagues at the field station and they had believed them to be photos of wild gorillas in Rwanda. "Your firm . . . has made a tremendously important advancement toward the captivity conditions of gorillas," Fossey wrote (Greene). Other observers noted that "Woodland Park has remained a model for the zoo world," and that "as far as gorilla habitats go ... Woodland Park's is the best in the world" (Greene).

This work and the attention it generated brought additional zoo projects to Jones & Jones, including the following internationally recognized work directed by Johnpaul Jones:

-

Tiger River Trail at the San Diego Zoo (honored with the "Best Exhibit" Award in Zoological Design by the American Zoological Association in 1989);

-

Asian elephant house at Woodland Park Zoo;

-

polar bear habitat at Point Defiance Zoo in Tacoma;

-

Honolulu Zoo master plan;

-

plans and exhibits for the Arizona-Sonoran Desert Museum;

-

the African Savannah master plan and exhibits for Australia's Perth Zoo;

-

the Jake L. Mamon Gorilla Conservation Research Center at the Dallas Zoo (1992);

-

the master plan for the National Zoo of Belize.

Heritage and Visitors' Centers

Johnpaul Jones also became involved in the design of heritage and visitors' centers in Washington and around the United States, also including several that garnered publicity and awards:

-

Gene Coulon Beach Park (Renton, recipient of the American Steel Association's First Honor Award in 1987, and one of nine projects in the nation selected for exhibit by the Architectural League of New York);

-

Newcastle Beach Park Buildings (Bellevue, Time magazine's Best Design of 1988);

-

the Southeast Alaska Visitor Center in Ketchikan, with Charles Bettisworth and Company, Inc.).

Beginning in 1991, Jones worked with environmentalist and entrepreneur Harriet Bullitt (1924-2022) to create the Sleeping Lady Mountain Retreat and Conference Center in Leavenworth. The first phase involved conversion of an underutilized camping site (known in the 1930s-1940s as Camp Icicle, headquarters for the Civilian Conservation Corps) to create the Retreat Center, later expanded to extend its use as a conference center. The center broke new ground for application of environmentally sensitive design principles and products, and was recognized in 2000 by the AIA with its national Energy and Architecture Award, and in 2001 with citation among the AIA's "Top Ten Green" projects in the nation.

In 2009-2010 Jones designed the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial Phase II, a long-sought recognition of the historical significance of the impact of the Asian American Exclusion Act on the island community, and especially on its Japanese American population.

Work for Native Cultures

Jones's work in advancing public consciousness of Native American heritage earned widespread recognition, including the AIA Seattle Medal in 2006:

"An area of [Jones's] concentration involves the interpretation of indigenous peoples' values, ways, and beliefs in creating projects celebrating Native American Indian cultures. Johnpaul has worked closely with Native American tribes throughout the US, incorporating their architectural and cultural heritage into the structures designed specifically to honor them. This direction had a special culmination in Johnpaul's design leadership with others over the dozen years of effort to realize the National Museum of the American Indian, which opened on the Mall in Washington, D.C. on September 21, 2004" (Medal).

At Seattle's Discovery Park, the hiring of Jones and his designs for the Daybreak Star Center (1977) and the People's Lodge expansion (2003) helped settle the years-long controversy that had pitted Magnolia Park residents against proponents of a Native people's cultural center, a struggle that included the 1970 "invasion" and occupation of the site by a group led by Bernie Whitebear and the United Indians of All Tribes Foundation.

The People's Lodge was a place for people of all cultures to experience Indian tradition and a range of cultural activities, and included a museum, a theater, and a library open to visitors, including the Seattle area's 45,000 Native Americans. At the time of the lodge's opening in 2003, Seattle Mayor Greg Nickels (b. 1955) predicted that "It will become a Seattle landmark, and it will be a landmark of national significance" (Maag II).

Jones's work on Native cultural centers includes the Longhouse Project on the Evergreen State College campus in Olympia, which received an Award of Excellence from the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians in 1996 "for assisting in the preservation of Indian cultural values and enlightenment of the public toward a better understanding of Indian people." Johnpaul Jones married Marjorie Sheldon on September 21, 1997, with ceremonies held at the Evergreen Longhouse.

He also prepared a redesign for the University of Oregon's Many Nations Longhouse at Eugene.

Tribal groups from around American have engaged him in the creation of plans and projects for a range of community and cultural functions, including:

-

the Agua Caliente Tribe Cultural Museum, Palm Springs;

-

the Aquinnah Cultural Center Master Plan for the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head at Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts;

-

the Colville Confederated Tributes Cultural Center Master Plan at Colville;

-

the De'aht Tribal Elders Longhouse center for Makah Indian Tribe at Neah Bay;

-

the Southern Ute Museum and Cultural Center for the Southern Ute Indian Tribe of Ignacio, Colorado;

-

the Spokane Tribal Cultural Center Master Plan for the Spokane Tribe Planning Department at Wellpinit;

-

the Tiwyekinwes Cultural Center Master Plan for Chief Joseph Band of the Nez Perce Indians at Nespelem;

-

New Mexico's Institute of American Indian Art.

At the time of this writing (2010), Jones has undertaken the design of the University of Washington's Native American Student Longhouse Center/House of Knowledge.

National Museum of the American Indian

Jones's expertise and reputation for successful design of a range of Native projects equipped him well for the challenges of completing the design of the National Museum of the American Indian on the Capitol Mall, the 16th museum of the Smithsonian Institution. In a publication about the museum, Johnpaul Jones writes:

"My own involvement with this building began before the National Museum of the American Indian was created. Sometime during the 1980s, I heard that the Heye Foundation was looking for a new home for the collections, and that Ross Perot was interested in acquiring them and moving them to Dallas. I wrote Perot to tell him I would love to work on his project, if it went through ... . [T]he consultations that began in the early 1990s were essential to the design of this building. The Smithsonian was able to bring Indian elders, Indian artists, Indian educators, and other Indian professionals into the process of creating the museum" (Blue Spruce).

The realization of a long-held dream for many, the museum design (originally conceived by a team that included Jones and was led by Canadian architect Douglas Cardinal, who later left the project) called for crafting a unique place with aspects of welcome for members of some 500 United States tribes, as well as multicultural American and international visitors. As the museum's website describes it:

"Extended collaboration resulted in a building and site rich with imagery, connections to the earth, and layers of meaning. The building is aligned perfectly to the cardinal directions and the center point of the Capitol dome, and filled with details, colors, and textures that reflect the Native universe" (www.nmai.si.edu).

Jones calls the building that resulted from this extensive process "The Rock." Quoted in a Seattle Times article, Jones notes that the museum "doesn't have a straight line in it." He continues:

"It centers around something very organic, that which is common to Indian communities around the nation. It centers around the four worlds: the natural world, the animal world, the human world and the spirit world ... . Within each one of those worlds is something that helped us in the design of this building, the site [and] the interiors" (Green).

Senator Dan Inouye (b. 1924) noted in his remarks at the museum's grand opening on September 21, 2004, that the design of the building in itself addresses dire social issues, laying the groundwork for healing long-standing injustices to the nation's first citizens.

The Confluence Project/Vancouver Land Bridge

Johnpaul Jones’s connection with the land and its history made him a natural participant in the Confluence Project, a decade-long project directed by Maya Lin to incorporate art into the reclamation of the Columbia River Basin and its history. The Vancouver Land Bridge ranks as the largest among seven projects that together trace 450 miles of Lewis and Clark's 1805 route. The project and the bridge element bring attention to the Native history of Washington. An October 2009 article in The Seattle Times noted that “The new bridge, the most visible part of the larger Confluence Project, aims to champion stronger ties to our environment and to Native Americans who contributed to the West's cultural enrichment,” as it

“reunites the landscape between the Columbia River and the old Fort Vancouver. ... It's a feat of engineering and a historical-restoration project all in one wide arc of an overpass. Designer Johnpaul Jones seems to have almost massaged the landscape, pulling it up and over the railway tracks and highway to connect Fort Vancouver with the Columbia River waterfront. ‘Like in the old days, you can now walk from the river to the fort and back,’ says Jones” (Easton).

An article in Landscape Architecture magazine quotes Jones’s description of the project: “We grabbed the prairie and pulled it over the highway” (Enlow).

Local, National, and International Recognition

Projects led by Jones have merited design recognition from local and national design and building industry organizations, and from the American Zoological Association. Award-winning designs include:

-

the Gorilla Habitat at Seattle's Woodland Park Zoo;

-

Tiger River Trail & Tree House at San Diego Zoo;

-

Longhouse Education & Cultural Center at the Evergreen State College;

-

Icicle Creek Music Center;

-

Sleeping Lady Mountain Retreat, Leavenworth

-

Mercer Slough Environmental Education Center in Bellevue (2009).

In 1980, the President's Award of Excellence from the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) recognized Jones & Jones for sparking the landscape-immersion era in zoo design at Seattle's Woodland Park Zoo. In 2003, the ASLA recognized Jones & Jones as the first recipient of its Firm Award, recognizing the firm's establishment of new standards of excellence in analysis, creative design, and the practice of landscape architecture.

Bringing Diversity into the Design Professions

Beginning in the 1980s, Johnpaul Jones committed himself to the complex task of encouraging young people of all backgrounds to aim high and to develop and exercise their gifts. Jones helped establish and empower the AIA Seattle Diversity Roundtable, originating at and named for a round table at Lowell's in the Market, where Jones met with other architects of color, including David Fukui, Tom Kubota, and Mel Streeter (1931-2006), along with Marga Rose Hancock (this writer), then executive director of the organization. Roundtable members organized outreach to K-12 schools in the area, established scholarships at the University of Washington, and in other ways helped many people from all ethnic, cultural, and economic situations to find a place in architecture.

Jones has also worked on diversity initiatives with colleagues at his alma mater, the University of Oregon, and with colleagues in the American Indian Council of Architects and Engineers and the National Association of Indian Architects and Engineers. He speaks extensively at professional conferences and at schools throughout the United States, modestly but compellingly offering his example in overcoming obstacles to achieve success in his life and work.

Honors

The University of Oregon School of Architecture and Allied Arts honored Jones in 1998 as the inaugural recipient of the Lawrence Medal, its highest honor to distinguished alumni, "in recognition that his accomplishments transcend architecture, landscape architecture, and historic preservation, and with enduring respect for his dedication to practice and to a life that honors social and cultural integrity at their foundation " (Medal). In 2005, the University of Oregon faculty selected Jones to receive its Distinguished Service Award, and in 2010, he was tapped to present the University's Commencement Address, in which he offered his thoughts on the topic “Indigenous Design -- Emerging Gifts" (University of Oregon News).

In 2006, AIA Seattle recognized Johnpaul Jones's contributions to the profession with the award of the local organization's highest honor for lifetime achievement, the AIA Seattle Medal, noting that

"His activism has attracted and encouraged many people of "different" backgrounds to consider and pursue design as a career, and to apply his example of design as a tool for healing and advancing community.

In his work and otherwise, Johnpaul takes his strength and guidance from the land — a design philosophy and a way of life which he attributes to his own roots in the Cherokee/Choctaw tradition ... . Jones's designs have won public and professional acclaim for their reverence for the earth, for paying deep respect to regional architectural traditions and native landscapes, and for heightening understanding of indigenous people and cultures of America ... . Johnpaul Jones's profound influence on the profession originates in his own humanity. His modest and gentle manner underlies enormous strength of character, while his profound idealism fires his passion to achieve an architecture embracing a rich cultural diversity. Quiet and unassuming yet with a uniquely commanding presence, he lets the power of design speak through him. Not only his ... colleagues but also the millions who visit projects touched by his unique vision benefit by the work and the example of this remarkable architect, who upholds our profession's highest aspirations to design excellence and social relevance" (Medal).

Jones was one of 10 recipients of the 2013 National Humanities Medals recognizing individuals or groups whose work improves the nation's understanding of humanities. He received the award for "for honoring the natural world and indigenous traditions in architecture" ("Awards & Honors"), the first time an architect has received this honor. President Barack Obama (b. 1961) presented the medals to Jones and the other recipients at a White House ceremony on July 28, 2014.

Jones's Thoughts

In 2006, when he received the AIA Seattle Medal, Jones offered these thoughts on his life and work:

"What I've realized over time is that it honestly takes the 'collective intellect' of the many partners and clients I've worked with to accomplish the best in design, and — through my American Indian heritage — I've come to understand that I am connected to something larger than myself. I think I now understand what my American Indian Grandmother and Mother were saying as I was growing up, and I've tried ... to make sure that I put what they said into practice.

Actually, it's what we share across all our diversities. It's not an American Indian vision or a philosophy. It's not a sacred path of enlightenment. It's something much more understandable: It's a canoe, here in the Northwest. It was sent to us by the ancestors to guide us, and help us know that we are connected to something larger than ourselves!

There is a sculpture by Indian artist Bill Reid that expresses this belief located at the Canadian Embassy in Washington, D.C. There is hardly any room in the canoe, it is full of animals, human, spirits, and nature. It is a canoe with a message, like most American Indian beliefs. The oneness of the canoe's message is that we are all connected and we're in it together. This sculpture is centered around the "Four Worlds" of my American Indian heritage. My Indian Grandmother gave these four worlds to me.

It's the diversity of projects at Jones & Jones over the last 40 years that have allowed me to use these four worlds effectively in planning and design: zoological projects; American Indian projects; and other regional architecture projects. What I've come to realize most of all over the last 40 years is that I can use my own diversity, the ancient knowledge my ancestors have given me, to solve and "enrich" architectural planning and design problems" (Jones, Medal).

A 2004 front-page article in The Seattle Times summed up Jones's achievements: "Jones doesn't just build buildings. He creates environments following holistic instincts, so his designs encompass both the practical and the spiritual ... . One of maybe 100 American Indian architects in the country, Jones helped lead a movement to diversify Seattle's architectural and design community" (Green).