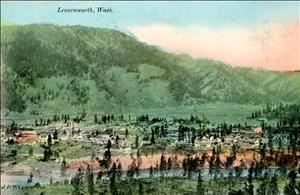

The town of Leavenworth in Chelan County occupies a spectacular location at the confluence of Wenatchee River and Icicle Creek, over which loom peaks of the North Cascade Mountains. The Wenatchee Valley was the traditional home of Native Americans, mainly the Wenatchi Tribe, for whom the Wenatchee River and Icicle Creek provided a limitless supply of salmon. Then opportunities for mining, logging, fruit growing, and railroad work drew settlers to the area. Although Leavenworth boomed for a time, it soon suffered from the unrealized promises of all of these ventures, and the Depression of the 1930s appeared to seal its fate. During the early 1960s two men from Seattle who had settled nearby inspired the local residents to revive Leavenworth as a tourist theme town. The alpine setting suggested the perfect motif: a Bavarian village. After several years of heroic volunteerism and financial sacrifice by longtime residents and crucial outsiders alike, it became successful beyond their imagining, developing into Washington’s second most popular tourist destination, after Seattle.

Beginning with a Cluster of Cabins

The nucleus of Leavenworth was a small cluster of log cabins called Icicle along Icicle Creek. Supplies had to be brought in from Ellensburg by pack trains. Frank A. Losekamp kept a store and was the first postmaster. Then the Great Northern announced plans to lay tracks through the Wenatchee Valley. The new, permanent town was named for Charles Leavenworth of Portland, a major stockholder in the Okanogan Investment Company that bought land along the right-of-way, providing incentives for Icicle residents to relocate. Other prominent members of the company were Jay P. Graves (1859-1948), Alonzo M. Murphy, and S. T. Arthur of Spokane. That same year the Great Northern built a roundhouse and machine shops at Leavenworth and began a tunnel to eliminate mountain switchbacks. The Great Northern provided the new town with its first doctor, contract physician Dr. George W. Hoxsey.

In addition to the exodus from Icicle, a number of prominent businessmen of Wenatchee relocated to Leavenworth, and by February 1893, the town claimed a population of 700. On April 1, 1893, the Leavenworth Real Estate and Improvement Company filed the first plat. Plats for additions followed in 1896 and 1898.

Mining of gold and other metals in the nearby Blewett Pass area and the Red Mountain Mining District held promise in the early twentieth century but eventually declined. Lumbering in the area of Lake Wenatchee provided more reliable employment. Logs were floated down the Wenatchee River to a sawmill the Lamb-Davis Lumber Company from Iowa built at Leavenworth in 1904. The company, which by 1906 employed 200 in its camps and mills, also founded Leavenworth’s first bank, the Tumwater Savings Bank, and eventually established waterworks and a light plant. When the town was incorporated on July 28 (or September 5), 1906, Coast Magazine listed its population at 1,000 and stated that it “enjoys prosperous conditions” (Coast, 194). Deed H. Mayar was elected mayor, H. E. Carr treasurer, and D. McCoy, George W. Hoxsey, C. Hansen, T. J. Coleman and H. X. Featherston councilmen.

Growing, Mining, Declining

Fruit culture in the narrow valley and lower mountain terraces around Leavenworth seemed promising in the early 1900s, as it was in the entire Wenatchee Valley. In 1901 the Icicle Canal Company began work on an ambitious irrigation system. However, in the immediate area of Leavenworth, most efforts to grow fruit were thwarted by the short growing season and by severe frosts. The canal system is still part of a network that continues to supply water to successful orchards in more benign microclimates farther down the valley, its old wooden flumes now replaced by pipes and previously leaking irrigation ditches lined with concrete.

The temporary boom resulting from mining, the railroad, fruit, and lumbering boosted Leavenworth’s population to 5,500, larger than Wenatchee at the time. Along with the boom came the usual excesses -- saloons, gambling, and brothels -- earning Leavenworth the label “the wildest town in the West” (Price, 8). Then during the 1920s, the sawmill closed and Great Northern moved its yards to Wenatchee and rerouted its tracks. Finally the Depression of the 1930s began a decline from which Leavenworth would not recover until reinventing itself as a tourist Mecca.

Re-inventing Leavenworth

In 1960, two friends from Seattle bought a failing country cafe on Highway 2, 15 miles up the valley west of Leavenworth. Highway 2, the Stevens Pass Highway, was a venerable cross-state route, but vastly more travelers between Seattle and points east chose the four-lane Interstate 90. Theodore H. “Ted” Price (b. 1923), a pharmaceutical representative, and Robert F. “Bob” Rodgers both had jobs that took them through Leavenworth regularly. They loved the river and the mountains and often returned to vacation in the area. They decided to quit their jobs and invest in the cafe, soon adding a motel. Bob had been stationed in Bavaria after World War II and loved that mountainous state in southern Germany that had once been an independent kingdom. The partners considered a Native American theme for their business, but decided upon a Bavarian motif so suited to the alpine surroundings. Their cafe, which they renamed the Squirrel Tree, and the motel that followed became successful, drawing a loyal clientele from throughout the valley and as far away as Seattle.

Although they would not move into Leavenworth until several years later, Price and Rodgers soon became involved in the community and its problems. The population was dwindling, and the town was something of an eyesore, with many unoccupied and dilapidated buildings surrounded by old cars and refrigerators. Many residents were on welfare. Nearby logging operations and the National Forest Service were among the few sources of employment. There was scant incentive for young people to stay. Improvements to Highway 2 had reduced the trip to Wenatchee to less than a half hour, inducing shoppers to abandon the remaining stores in Leavenworth. Furthermore, when the old high school was condemned, the community was torn apart over the funding and location for a new one.

Price and Rodgers were aware of discussions already underway of ideas for revitalizing the town. Most of them centered on attracting some sort of industry, probably along the river. As skiers and hikers, the two outsiders were keenly aware of the recreational attributes of the Leavenworth area. (In fact, the town had long hosted the annual Leavenworth Championship Ski Jumps, established by Norwegian Magnus Bakke. It hosted the U.S. championship competitions in 1941, 1959, 1967, and 1978. The most renowned jumper from Leavenworth was Ron Steele, who competed in the 1972 Olympics.) In addition, the Stevens Pass ski area was nearby, and of course, spring, summer, and fall in the upper Wenatchee valley offered hiking, hunting, fishing, and mountain climbing.

Project LIFE Begins Life

In 1962 the Chamber of Commerce contacted the Bureau of Community Development at the University of Washington (also referred to as the Office of Community and Organizational Development), which provided them with a self-study program designed for enabling struggling towns to come up with solutions to their problems. The umbrella organization that emerged was called Project LIFE, for Leavenworth Improvement for Everyone. The University of Washington guidelines specified many subcommittees, but oddly, there was none for tourism until Price urged it. The UW consultant consented, if Price would chair it, to which he readily agreed.

Price and Rodgers maintained that tourism offered far more potential than industrial development for Leavenworth’s revitalization. Its location, a comfortable two-hour drive from Seattle, was an advantage. Even more compelling was its unsurpassed mountain scenery, which had been described as far back as 1904 as:

"pre-eminently beautiful. Immediately to the west of the town rise the colossal Cascades, with marked abruptness. ... Arising more gently to the north and south are spurs of the great mountain range. To the east extends the valley through which flows the Wenatchee River" (Steele, 729).

One of the community groups working most actively toward revitalization of Leavenworth was the Vesta Junior Women’s Club, which in 1964 was the first women’s club in Washington to win the Sears Roebuck and General Federation of Women’s Clubs award for outstanding community service. The prize was $10,000 for the club’s work with Project LIFE; its part in the resolution of the school dispute, which resulted in a fine new Cascade High School in 1966; support for a fire department levy; and cleaning up and beautifying the cemetery and city park.

Even before any plan for revitalization was on the drawing board, Price introduced the idea of what became the Washington State Autumn Leaf Festival. He and Rodgers had been sending out annual autumn leaf publicity to encourage patronage of their business and shared the idea with Leavenworth, which hosted its first such festival from September 19-27, 1964.

Ted Price and Bob Rodgers

When Price and Rodgers first advanced the idea of a theme town based on tourism and the adoption of the Bavarian village motif, as outsiders they were working with a double handicap. Not only were they originally from Seattle, but their current Squirrel Tree business and home were miles outside of town. Pauline Watson, a local leader, who worked closely and supportively with their ideas and activism on behalf of Leavenworth, put it this way:

“Small town merchants don’t want to be told what to do, and they don’t want to be told by somebody from out of town. ... You folks lived in Seattle before ... and now you are trying to tell us what we should do. It was going over like a bomb! Not that it wasn’t a good idea, it was simply coming from the outside” (Price, 40).

Even after they moved into town, the prejudice persisted, possibly fueled also by their status as bachelor friends rather than family men. The two partners left Leavenworth in 1986 and eventually retired to Palm Springs. They did not come out as a gay couple until years after their departure from Leavenworth, but suspicions and prejudices may have existed during their residence there. Later Ted recalled wryly that articles in the national press credited a number of people, but not them, with the idea of transforming Leavenworth into a Bavarian village. As transformation of the town progressed:

“I remained troubled by the attempts of some individuals to tell the story of Leavenworth’s revitalization in fanciful ways. Essential elements of what happened were being left out of the official accounts, and people who had little or nothing to do with creating Bavarian Leavenworth were starting to be named as responsible ... soon new facts about the revitalization were being invented to give recognition to a few old timers” (Price, 100).

Not only were the names of Ted Price and Bob Rodgers often omitted from official reports generated by committees in which they had major involvement, but most subsequent newspaper and magazine articles on the Leavenworth phenomenon leave the impression that the transformation came about solely through the efforts of longtime local residents.

Getting to Bavaria

It was a hard job to convince some community leaders to consider tourism rather than industry as their life line. Once that was accomplished, the next hurdle was to talk them out of a Gay Nineties theme in favor of the Bavarian village idea. Price and Rodgers launched a number of their own efforts independent of the city fathers and mothers. One was a trip in 1965 to Solvang, California, to see the formerly sleepy farming town that had become a theme town based on its Danish heritage. They brought back slides of businesses remodeled in the Danish style, helping to convince the local leaders of the viability of a theme town.

Although a few Leavenworth residents could claim German descent, unlike Solvang, the town could make no compelling ethnic argument for the Bavarian village idea. It had to be based on something else: the beautiful alpine setting, so similar to that of such Bavarian towns as Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Mittenwald and Oberammergau, the home of the famous Passion Play. The elevation of Leavenworth is 1,170 feet, and nearby peaks rise to more than 8,000. Furthermore, the architecture made practical sense. The heavily beamed, gently sloping roofs with wide overhangs of the Bavarian style are ideal for the heavy snowfall of Leavenworth.

Price and Rodgers decided to sell the Squirrel Tree and acquire as much Leavenworth property as possible with an eye to remodeling it in Bavarian style. Major property owners soon took out loans in order to transform their own buildings. But the question was how to do it. Miraculously, Earl Petersen, the designer of Danish Solvang, contacted Ted Price to offer his services free of charge! Petersen and another designer with Old World experience, German-born Heinz Ulbricht of Seattle, guided the remodeling to ensure the utmost authenticity. Ulbricht and his family later moved to Leavenworth.

The first building to be remodeled in the Bavarian style was the Chikamin Hotel which owner LaVerne Peterson renamed the Edelweiss after the state flower of Bavaria. Mayor Wilbur Bon, Bob Brender, president of the Chamber of Commerce, and Russell and Vera Lee, publishers of the Leavenworth Echo, Owen and Pauline Watson and other property owners got behind what they called “Project Alpine” (Price 54). Everyone involved in the restoration took out loans to the point of great risk in order to achieve authenticity. As Ted Price recalled, "we were only a handful of people who were broke and promoting very big, seemingly impractical ideas" (Price 55). They accomplished the entire remodeling effort over a number of years without recourse to government money. Other residents sacrificially volunteered professional skills, time, and labor. Specialized workers were brought in for Old World techniques in stucco, timbering, and murals.

On March 21, 1968, Leavenworth was one of 11 cities to receive an All American City Award from Look Magazine and the National Municipal League. According to the Leavenworth Echo, Leavenworth “was honored for pulling itself out of a serious economic slump” (Echo, Sonnenschein Edition for 1969-70, 1). Not surprisingly, Ted Price had a major hand in preparing the application.

The Hand of Carolyn Schutte

Another outsider who became an angel of Leavenworth was Carolyn Schutte (d. 1975). This wealthy Seattle woman had often brought guests to the Squirrel Tree and had befriended Price and Rodgers. Over several years, she quietly bought Leavenworth property, including part of the riverfront that would eventually become the major park. When she realized that Price and Rodgers were on the verge of bankruptcy and that Ted was nearing a nervous breakdown with stress and overwork, she took the two of them on an all-expense-paid trip to Europe, particularly Bavaria, where they took photographs and stocked up on authentic merchandise for the gift shop they by then owned in Leavenworth.

One of the holdouts against the Bavarian village idea had been Robert B. Field (d. 1967), longtime banker who had arrived in Leavenworth in 1910. From his perspective in a distinguished house built in 1903 by the Lamb-Davis Lumber Company overlooking the Wenatchee River, there was no need for such a change, and he publicly opposed the idea until his death in 1967. In 1968 Carolyn Schutte bought Field’s home and the adjoining half mile of riverfront property, which had been his Bent River Arabian Horse Ranch. At her suggestion, Price and Rodgers moved into the house and bought it from her a few years later. In 1972, Schutte deeded the valuable river frontage property to the city of Leavenworth. A substantial portion of what is now Riverfront Park is the result of this gift. The Field home later became the Haus Lorelei Bed and Breakfast and now houses the Upper Valley Museum.

Designing and Building

In order to ensure continuing authenticity, the town created the Leavenworth Design Review Board, which became official on July 16, 1970. All construction and remodeling in Leavenworth must meet not only the usual codes but also the Bavarian styles stipulated by this board. Many upscale new private homes along the Wenatchee River and Icicle Creek voluntarily adhere to these stipulations. Today (2010) the presence in town of a Chinese restaurant and an Australian import shop suggest that absolute Bavarian purity has been hard to maintain.

Although the remodeling of privately owned buildings was achieved without any government money, the city took advantage of public grants to acquire and develop waterfront property for park and recreational purposes. The Washington State Inter-Agency Committee for Outdoor Recreation (IAC) provided communities with matching funds for these purposes. Because the federal government then matched both city and state funds, the community only had to raise 25 percent of the total. In addition, Carolyn Schutte donated her property along the river and Price and Rodgers bought five waterfront acres across the river to donate. Today Waterfront Park is one of Leavenworth’s most beautiful features. Resident Harry Butcher and others also helped to make it a reality.

All that Leavenworth had achieved came close to being destroyed by the Great Fire of 1994, forest fires that swept down Tumwater Canyon and over Icicle Ridge to within a few feet of Leavenworth. In late July and early August wildfires burned 180,000 acres of forest in Chelan County. Leavenworth mayor Mel Wyles said of the threat to Leavenworth, “There were cinders falling all over around my house here in town” (Price, 155). Nineteen homes were destroyed in the region but, miraculously, there were no fatalities, and downtown Leavenworth remained intact. Fires originating in the town itself had plagued Leavenworth’s early history, burning down buildings in 1894, 1896, 1902, and 1904, but the 1994 fire could have been far more catastrophic if it had swept into the town center.

Thronging to Leavenworth

Tourists were not long in thronging to Leavenworth, attracted not only by the scenery, recreational opportunities, shopping, and European flavor of place, but by special events and festivals. The normal population of around 2,500 can swell to 10 times that on holiday weekends, when dozens of tour buses disgorge their passengers onto the main streets. Some two million tourists visit Leavenworth every year, and the sales taxes their purchases generate benefit the state coffers.

Each season has its festival (or more than one). The Fall Leaf Festival, Oktoberfest, the Village Lighting Festival, the Bavarian Ice Fest, Maifest, yodeling and accordion festivals, wine tastings, and a host of other events bring throngs of tourists. Just up Icicle Canyon the exquisite Sleeping Lady Retreat and Conference Center sponsors cultural and artistic events year round, including a world-class summer chamber music festival.

Tourism: A Devil's Bargain?

Tourism has become a popular topic among social scientists, many of whom take a dim view of its effects on local communities. In a milestone work on tourism in the West, aptly titled Devil’s Bargains, Hal Rothman suggested that “the embrace of tourism triggers a contest for the soul of a place” (Rothman, 11). People lose the sense of being from somewhere real. In the view of some in Leavenworth, community cohesion has suffered. Letters to the Leavenworth Echo, particularly in the 1970s and 1980s, reveal considerable dissatisfaction over the issues of parking, shopping, cost of living, and the decline of old-fashioned neighborliness. One letter, objecting to the Echo’s editorial support for the Bavarian village development, opined: “How much more do we have to give up for tourism? ... Get your head out of the sand and quit letting tourism bury us!” (Frenkel, 8).

Sixteen years after its original consultation with Leavenworth, the Office of Community and Organizational Development at the University of Washington conducted a survey of residents and found that only a slim majority of the town’s residents approved of further Bavarianization. Those living in the surrounding rural areas were even less enthusiastic. Local opinion seems to be changing, however, possibly because there are fewer left to remember the pre-Bavarian days, with nostalgia or otherwise. In fact, many current residents of Leavenworth were born elsewhere.

Parking has always been difficult for tourists and locals alike. Another seemingly intractable problem is that real estate and rental prices have escalated, pricing out the legions of low-salaried workers who staff restaurants, shops, and gas stations, and who clean streets, remove snow, and tend the flower boxes. Ordinary shopping has been another problem. One could buy a cuckoo clock, nutcracker, or even lederhosen for the dog in the Bavarian village, but the more mundane necessities of life such as groceries have been hard to find.

A 1997 article in Journal of the West asserted that Leavenworth has “discard[ed] its heritage” and that:

“Children growing up in Leavenworth in the 1990s experience a hometown dedicated to service outside interests through tourism; the original landscape and history that made the community unique is ignored. The impact is accentuated by false storefronts, ignores local history, and is responsible for confusion among generations. Leavenworth exemplifies other middle-class recreational theme towns in the West. The city promotes a theme-park mindset that ignores the natural history, cultures, and landscape that define the region” (Sudderth, 81).

A Real Town

One could argue that Leavenworth’s replica Bavarian village, so like its actual models in its alpine setting, does not ignore its “original landscape.” The valley, the mountains, and the river are still there! Furthermore, the town even contains remnants of its authentic past. Leavenworth has a current (2010) year-round population of 2,300, a seasonal population of affluent people with vacation homes and condominiums, plus the hordes of tourists who spend a weekend or a month in motels, bed and breakfasts, and vacation rental cabins. Yet behind the main Bavarian streets there remain modest dwellings that once housed the timber and railroad workers. There was even in recent years a temporary revival of the sawmill era, when the Longview Fibre Company built a mill in 1991. At the time of its closure in December 2006, it employed approximately 100.

The opening in 2002 of the Upper Valley Museum, occupying the historic Robert Field house, demonstrates that the town has not discarded an interest in its history. Its vision statement describes “a culturally diverse community that is recognized for a deep and inclusive appreciation of its past, a broad understanding of its present and a strong investment in its future” (Museum website).

Although a theme town, Leavenworth works toward the same sorts of goals as do many ordinary towns, thereby benefiting local residents and tourists alike. The tasteful new shopping plaza just outside of town has now made it easy to shop locally for groceries and other necessities. To open in September 2010, a $14.4 million new Cascade Medical Center will greatly expand and update the 1970 facility. In 2007 funding measures for the new facility passed by wide margins, and talented new physicians have joined those who decided to stay. According to Rufus Woods, publisher of the Wenatchee World:

"People may not remember that the medical center was in horrific condition in the 1990s. What transpired in the intervening years is one of the great stories of transformation in which community members came together to study ways to save the facility from bankruptcy, key doctors decided to make a commitment to stay in the valley, as well as critical financial and strategic decisions that allowed the organization to rise like a phoenix out of the ashes” (Woods).

Leavenworth's Quality of Life

In 2009 Leavenworth’s downtown master plan won the Best Physical Plan Award from the Washington American Planning Association/Planning Association of Washington for its proposal for improved signage and design of plazas and grand entries to downtown. Working with Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad, Leavenworth interests have secured Amtrak service over BNSF tracks. The new Festhalle for trade shows, conventions, concerts, plays and other gatherings seats 1,000. For the kids, there is a swimming pool and a skate park.

Improved schools and medical facilities, unsurpassed recreational opportunities during all seasons of the year, and one of the most spectacular settings in the West should bode well for keeping established residents and attracting newcomers. The people of Leavenworth continue to build on the tradition of volunteerism and civic activism begun by an earlier generation of local residents and significant outsiders, not only to maintain their Bavarian village as Washington’s premier theme town, but to enhance the quality of life for all its residents.