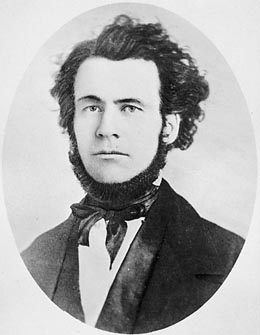

Samuel Royal Thurston's (1816-1851) political ambitions were greater than his short life allowed. Oregon Territory's first delegate to the U.S. Congress, Thurston is credited with passage of the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850, legislation that attracted thousands of settlers to the region in the following decade. Born and educated in Maine, Thurston became a lawyer -- admitted to the bar in 1844 -- and for a time edited the Burlington Gazette in Iowa. He moved to Oregon in 1847, where he practiced law and was elected as a Democrat to the 31st Congress, serving from March 4, 1849, to March 3, 1851. Thurston did not live to see the success of his legislation and the rapid growth it would bring to the Oregon Territory. In April 1851 he died aboard ship while returning home from Washington D.C. He was buried in Acapulco, Mexico, but eventually reinterred in the Salem Pioneer Cemetery in Salem, Oregon. Thurston County bears his name.

“Go West Young Man…”

Samuel Royal Thurston was born on April 17, 1816, in Monmouth, Kennebec, Maine, the only child of Trueworth Thurston and Priscilla Royal. Trueworth died young and Priscilla moved with Samuel to Peru, Oxford County, Maine. Samuel became a member of the Methodist Episcopal Church and even in his teens he was known locally as a persuasive speaker at church revival meetings and Democratic Party rallies. Adults encouraged him to pursue a career in the legal profession. Thurston attended Wesleyan Seminary in Readfield, Maine, and Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, then studied law, graduating with honors from Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, in 1843. He was admitted to the bar the following year.

With a promising future, Samuel attracted the attention of Maine’s ex-Governor Robert P. Dunlap (1794-1859), who took Thurston into his law firm while he was still an undergraduate. Here Samuel gained first-hand political experience and made important contacts. Upon graduation from law school, he married Elizabeth F. McClench (1816-1890) and the couple moved to Brunswick, Cumberland County, Maine, where Thurston set up his first law practice.

Samuel and Elizabeth moved to Burlington, Iowa, in 1845 and Thurston edited the Burlington Gazette for two years. In 1847 they set out for Oregon Territory -- now with a one-year-old son, George -- traveling by ox team and wagon along the Oregon Trail. They arrived in Hillsboro in Tualatin (now Washington County) that year and Samuel began practicing law. A daughter, Elizabeth, was born to them two years later in Oregon.

Politics in Oregon Country

Increased interest in the Oregon Territory had followed Lewis and Clark’s arrival at the coast in 1805, and from 1818-1827 the U. S. and Britain jointly occupied the region. Through a treaty with Britain, Oregon was finally defined as U.S. territory in 1846. A population that for decades had been primarily native tribes, fur trappers, and missionaries was rapidly changing with the arrival of increasing numbers of settlers. Power in the region was shifting from domination by the British Hudson’s Bay Company and its chief agent, Dr. John McLoughlin (1784-1857). It is likely that Thurston was drawn to Oregon through his Methodism. Missionary Jason Lee (1803-1845) had established a mission on the Willamette River in the 1830s and encouraged settlement in the Willamette Valley.

When a provisional government was formed with the Organic Act of 1843, settler’s land claims were recognized, giving claimants 640 acre tracts, but when Oregon Territory was officially established on May 14, 1848, these claims were nullified. Settlers clearly needed to resolve the land issue. When elected to Congress, Samuel Thurston would make this his first order of business. But by no means was it the biggest issue of the day -- that issue was slavery, and it would soon divide the nation.

Federal legislation banned the further spread of slavery as early as 1786, and as the U.S. expanded west and Oregon’s provisional government upheld the anti-slavery law. But settlers brought their pro- and anti-slavery views with them -- a few even brought their slaves -- and the topic was strongly debated. The West was of special importance in the national debate, since politicians could oppose slavery in the new territory while allowing it to continue in the South where it was deeply entrenched. Thurston expressed in an 1850 address to Congress that, although settlers in Oregon Territory predominantly opposed slavery, they also feared the arrival of blacks, who might marry natives and thus pose a greater threat to what was still a small white population.

The slavery debate slowed passage of Oregon statehood, which Thurston did not live long enough to see. A state constitution was drawn in 1857, and the issue finally put to public vote. Oregon voters upheld the anti-slavery law, but at the same time excluded African Americans -- as well as Hawaiians -- from Oregon when it became a state. Hawaiians had made up a large portion of the territory’s work force and most soon returned to the islands.

Local native tribes struggled. The Clatsop and Nehalem (Tillamook) met on August 5th and 6th of 1851 at Tansey Point at the mouth of the Columbia River and signed a treaty with the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Anson Dart (1797–1879). Although the Tansey Point Treaties were sent to Washington, D.C. for ratification, the process was blocked by Oregon Territory Representative Joseph Lane (1801-1881). (Thurston had died a few months earlier). The treaty was never ratified, creating a legal tangle for the Tillamooks that left them out of later treaties.

Congressman Thurston

While there was little white political infrastructure in the territory, pioneers brought their opinions with them and most considered themselves either Democrats or Whigs. The majority were Jacksonian Democrats. Thurston was a Democrat, but he drew both Whig and Methodist Mission Party support and was chosen as a legislator to the provisional assembly in 1848. As an early Oregon historian characterized him: “He was a ready speaker, ambitious, and not over scrupulous” (Gaston, 192).

Party lines were hardening and when a Whig newspaper, the Oregonian, was planned, Thurston looked for an editor to begin a rival publication more sympathetic to the Democrats. In 1850 he convinced an East Coast printer, journalist, lawyer, and town clerk, Asahel Bush (1824-1913), to come to Oregon and begin a newspaper. In a letter to Bush in 1850, he wrote: “Most of all, have the good of Oregon in view, and let all other things, parties included, be secondary. Treat your opponents with dignity and courtesy, but with decision, ability and firmness” (Mahoney). Bush established the Oregon Standard, which became a highly influential publication.

Samuel Thurston was elected as the first Oregon Territorial representative to the 31st U.S. Congress and served from March 4, 1849 to March 3, 1851. His persuasiveness as a speaker led to passage of the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850, not an easy task when influential people, including American statesman Daniel Webster (1782-1852), declared the Northwest worthless, and government attention was chiefly focused on growing tensions between the slave and free states. Both the Compromise of 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Act were enacted in this same congressional session. But issues of the West were also in the forefront as California became a state and Utah was organized as a territory in 1850.

Donation Land Claim Act

Thurston convinced legislators of the growth potential in the Pacific Northwest and the need to recognize the property claims of those already in the region, as well as to establish structure for new claims. The number of white settlers was growing quickly, and there were also troubles with native tribes -- the killing of Dr. Marcus Whitman (1802-1847) and his wife Narcissa (Prentiss) Whitman (1808-1847), and the Cayuse war (1848-1855).

On September 27, 1850, the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 took effect, creating a powerful incentive for settlement of the Oregon Territory (eventually Oregon, Idaho and Washington) by offering 320 acres at no charge to qualifying adult U.S. citizens (640 acres to married couples) who occupied their claims for four consecutive years. Amendments in 1853 and 1854 continued the Act but cut the size of allowable claims in half. The Act was a precursor to the Homestead Act of 1862.

Under the Donation Land Claim Act, an Office of Surveyor-General of Public Lands in Oregon Territory was formed, a procedure for land surveying was established, and donations were made to settlers of allotted public lands. Few other congressional acts in U.S. history were as important in opening the west for development and shaping the region’s geography and politics. Within five years, the number of claimants numbered more than 7,000, most settling in the Willamette Valley.

Samuel Thurston and John McLoughlin

Section 11 of the Land Claim Act was a vendetta against former Hudson's Bay agent John McLoughlin, and sought to deny him a land claim in Oregon City. Thurston attempted to discredit McLoughlin on the basis of citizenship. He further accused McLoughlin of repeatedly trying to stop territorial development and personally profiting from land sales. John McLoughlin was now an old man and Oregon had been his home for many years. He had retired from the Hudson’s Bay Company and applied for U.S. citizenship. The Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 provided that McLoughlin's claimed property at Oregon City be given to the state legislature.

McLoughlin protested Thurston’s claims saying:

“He says that I have realized, up to the 4th of March, 1849, $200,000 from the sale of lots; this is wholly untrue. I have given away lots to the Methodists, Catholics, Presbyterians, Congregationalists and Baptists. I have given 8 lots to a Roman Catholic nunnery, 8 lots to the Clackamas Female Protestant Seminary, incorporated by the Oregon Legislature. The Trustees are all Protestants, although it is well known I am a Roman Catholic. In short, in one way and another I have donated to the county, to schools, to churches, and private individuals, more than three hundred town lots, and I never realized in cash $20,000 from all the original sales I have made.

If I was an Englishman I see no reason why I should not acknowledge it; but I am a Canadian by birth, and an Irishman by descent ... . I declared my intention to become an American citizen on the 30th May, 1849, as any one may see who will examine the records of the court, in this place. Mr. Thurston knew this fact — he asked me for my vote and influence. Why did he ask me for my vote if I had not one to give?? I voted and voted against him, as he well knew, and as he seems well to remember” (Holman, 132-133).

McLoughlin's claim was denied. He became a U.S. citizen and died in 1857, leaving his heirs an estate valued at $142,585, not counting $29,414 in debts owed him that the appraisers considered uncollectible. His real estate holdings were valued at $86,170. The appraisers noted that the legislature had yet to seize any of McLoughlin's land, but that approximately half of it was legally subject to seizure. Assuming that all the disputed land was seized, and that none of the debts could be collected, McLoughlin's estate still amounted to more than $100,000 in 1857 dollars -- more than $2.7 million today (Morrison, 473-74). Today Oregon City recognizes the McLoughlin Neighborhood District which overlooks Abernethy Creek.

A Fateful Voyage

Returning from a U.S. congressional session in Washington D. C., Thurston traveled through the Isthmus of Panama, the quickest route home. He contracted “Panama fever” (Yellow fever/Chagres fever) and died aboard the ship California on April 9, 1851, a week short of his 35th birthday. Crew buried him in Acapulco, Mexico. Two years later the Oregon territorial legislature brought his body back and buried him in Salem’s I.O.O.F Cemetery, now known as the Salem Pioneer Cemetery. A large crowd attended the service, and a publicly funded monument of Italian marble was erected to his memory. The inscription reads:

“Here rests Oregon’s first delegate -- a man of genius and learning.

A lawyer and statesman.

His devotions equaled his wide philanthropy, his public acts are his best eulogium.”

Erected by the people of Oregon.

On January 12, 1852, Thurston County was created by the Oregon Territorial legislature. Originally part of Lewis County, the new county originally was to be named for Michael T. Simmons, who led the first party of American settlers into the Puget Sound basin. Instead it was named in honor of Oregon Territory's first delegate to Congress, Samuel Royal Thurston.