Earl Averill -- he went by his middle name -- was a relatively small player from a small town who made it big in major league baseball. Born, raised, and retired in Snohomish, he didn’t begin his big-league career until 1929 when he was nearly 27, but quickly made up for the late start. In an era when many of the game’s legendary players were in their prime, Averill was an immediate and perennial star for the Cleveland Indians. He was selected to baseball’s first six All-Star Games and batted .318 over a 13-year career. His Cleveland team record for home runs in a career lasted 57 years; his runs-batted-in record still stands. Fans loved him and opponents respected him, but baseball writers choosing candidates for enshrinement in the sport’s hall of fame were not as impressed. They passed over him for more than three decades. Finally, a special selection committee made him a unanimous choice. In 1975, he became the first Washington state native to be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. By then he had long been his hometown’s most famous citizen. In fact, his nickname put the town in baseball’s lexicon. He was called and is remembered as The Earl of Snohomish.

From Mills to Diamonds

Howard Earl Averill was born on May 21, 1902, the third child of Jotham (1861-1904) and Anna (1870-1952) Averill. Snohomish had about 2,000 residents, and 1st Street had yet to be paved. Not much is known about his childhood, except that Averill grew up playing baseball on a field cleared of tree stumps and rocks by townspeople. Equipment was crude, organization minimal. Players on that field quite likely used homemade balls cobbled together with shoe leather. Averill shined at baseball but gave it up at age 15 because he had a condition known as “a dead arm”; he wasn’t able to make throws from the outfield. About the same time he quit school to go to work, taking a variety of jobs in construction, lumber mills, and the greenhouse owned by his older brother, Forrest "Pud" Averill (1892-1981).

In 1920, the Pilchuckers, a Snohomish town team named after the nearby Pilchuck River, was formed. Averill was among those invited to try out. He made the team and played on it for several seasons. On May 15, 1922, he married Loette Hyatt (1906-2001). He was 19, she was 16. They would have four sons -- Howard (b. 1923), Bernard (b. 1925), Earl Douglas (b. 1931), and Lester (b. 1934) -- and remained married the rest of Averill’s life.

Local people were so convinced of Averill’s baseball ability that they paid his way to the Seattle Indians camp in San Bernadino, California, for a tryout in 1924. He was released and told that he didn’t have what it takes to play in the Pacific Coast League. Embarrassed by failing the tryout, Averill went to Bellingham where the town team took him on and found him a county maintenance job. He had an undistinguished season, batting about .269, and then played a few exhibition games for Everett.

Getting Noticed

Averill’s baseball fortunes changed dramatically in 1925. Back in Bellingham for another season, he hit better than .400. (A batting average of more than .300 -- or three hits for every 10 times at bat -- is considered good.) The surge in his average caught the eye of the San Francisco Seals, a powerhouse team in the Pacific Coast League. The Seals sent him to Anaconda, Montana, where he was ostensibly paid to work in a smelter but was really there to play for the town team. In the language of baseball, he "tore up" that league, again hitting better than .400 and leading his team from last place to just one game out of first by season’s end. From there, he went to the San Francisco area to play in the semi-professional California winter league.

The Seals invited him to their spring training camp in 1926. He traveled at his own expense, driving an Oldsmobile he later described as ancient, and this time his tryout was a success. Despite being loaded with outfielders, the Seals signed him to a contract and made him their centerfielder. His batting average topped .300 in each of the next three seasons. In 1928, when the Seals won the league championship, he drove in a league-leading 173 runs, a staggering total. In the Los Angeles area, he batted .500.

By then it was clear he had major league talent, even though he hadn’t had much coaching. "Nobody ever taught me much of anything. You were on your own when it came to fundamentals," Averill said in 1974. "Nobody ever did teach me anything, really" (Johnston, The Seattle Times, 1974).

Rookie Sensation

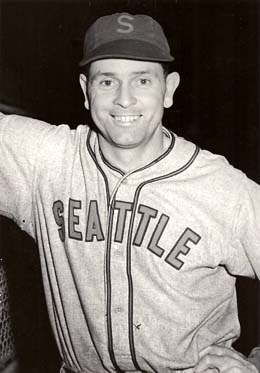

After the 1928 season, the Seals sold Averill to the Cleveland Indians of the American League. The man who had been told he didn’t have what it takes to play in the West’s top minor league was now a major-leaguer. And a high-priced one at that. Accounts of the deal vary, but the amount the Indians paid was widely reported to be $50,000. Averill said he got $10,000 that year in bonus and salary. "I thought that was pretty good pay at the time," he said. "What bothered me was I might not make the club. They (the Indians) said I wasn’t big enough. I was the smallest man on the team" (Moore, Everett Herald, 1983).

He might have been shorter than most, but he had a powerful build and bulging forearms, a physique that led to him being called Rock. Still, initially his height was a concern to some. When Indians owner Alva Bradley got his first look at Averill, he said to general manager Billy Evans, "You paid all that money for a midget." Evans replied, "Wait until you see him with his shirt off" (Dolgan, Cleveland Plain Dealer, 1996).

Averill was just one month shy of his 27th birthday when he made his major league debut. It was Opening Day, April 16, 1929. In his first at-bat, facing Detroit pitcher Earl Whitehill, Averill hit a home run. He was the first American League player ever to launch his career that way. "The cards are usually stacked against the debut of the high priced rookie in baseball. Once in a dog’s age, the rookie turns the tables and makes good from the start. The latter is true of Earl Averill," wrote Frank Getty, United Press Sports Editor. His story ran in the April 18, 1929, Everett Herald under the headline "Sports Scribes Go Into Ecstasies Over Playing and Hitting of Averill." The headline was misleading in the sense that no sports writers were mentioned, but it accurately reflected the mood of Cleveland’s manager, Roger Peckinpaugh. "He’s the best looking youngster to come up in a long time," Peckinpaugh said about his new centerfielder (Getty, United Press, Everett Daily Herald, 1929).

A Star Is Born

Averill finished his rookie season with a .332 batting average, 97 runs batted in and a team-record 18 home runs. That performance earned him a raise to $12,000 a year. "It was a lot of money for a second-year man," he said, "but I could hit with the best of them and I was the fastest in the league going down to first. Yes, and in the field too" (Johnston, The Seattle Times, 1974).

For their money, the Indians had a bona fide star. Averill was even better in his second year, batting .339 and driving in 119 runs. In September of that 1930 season, he became the first major leaguer to hit four home runs in a doubleheader. He finished the day with 11 runs batted in, still an American League record. In 1931 he hit .333 with career highs in home runs (32) and runs batted in (143). In 1932, he hit 32 home runs again.

Fearful of him as a hitter, the Boston Red Sox walked him five consecutive times in one game. Boston’s Ted Williams, one of baseball’s greatest hitters, later compared Averill to a pair of baseball legends. "He was treated with the kind of respect usually reserved for imposing specimens like (Jimmy) Foxx and (Lou) Gehrig," Williams said (baseballalmanac.com). In 1933, the All-Star Game was created and Averill joined Foxx, Gehrig, and Babe Ruth on the American League squad. It was the first of six consecutive All-Star Game selections for Averill, firmly putting his name alongside the sport’s all-time greats.

Big Fields, Big Bats

It was an era of baggy flannel uniforms, train travel, and big ballparks. When Averill joined the Indians, they played their home games in League Park, where the fence at the deepest part of center field was a whopping 460 feet from home plate. The distance at the right field foul line was only 290 feet but the screen separating the field from the seats there was 40 feet tall. Beginning in July 1932, the Indians also played home games in Cleveland Municipal Stadium, which had an even bigger center field. It measured 470 feet -- 60 feet farther than at Jacobs Field, the Indians’ home starting in 1994.

Averill thrived in both settings. Despite never weighing much more than 170 pounds, he favored heavy bats, some as heavy as 44 ounces. As he waited for the pitch, he held the bat low, rather than at shoulder height like most batters. A trio of former pitchers who were among his Cleveland teammates described Averill’s hitting style in 1996. Mel Harder: "When he hit the ball, it looked like a golf ball. He'd hit them in any park. League Park wasn't that easy for homers because of the 40-foot wall. He hit a lot of liners against the wall that would have been homers somewhere else." Mel Hudlin: "He was what we called a swing hitter. He swung the bat like a broom, didn't use much wrist. There were very few who hit like that." Al Milnar: "He had great timing, and it was his nature to hit it through the middle" (Dolgan, Cleveland Plain Dealer, 1996).

That tendency took its toll on opposing pitchers, most famously Dizzy Dean, a future Hall of Famer, then with the St. Louis Cardinals. At the 1937 All-Star Game in Washington, D.C., Averill hit one of Dean’s pitches right back at him, breaking his toe. Dean was never the same after that. The injury caused Dean to alter his pitching motion, leading to arm trouble and eventually ending his career.

Hometown Hero

Averill’s competitiveness also came out on the base paths. From the vantage point of retirement, he observed that most of his doubles "were singles that I ran out. Some batters were satisfied with singles" (Moore, Everett Herald, 1983).

The combination of these traits gave opponents fits. Lefty Gomez, a Hall of Fame pitcher for the New York Yankees, said, "Whether New York was at Cleveland or Cleveland was at New York, you were hoping he had a bad back or something. Earl could hit me in a black tunnel with the lights out" (Beard, Everett Herald, 1983).

Averill hit better than .300 in each of his first six seasons, but had a rougher time in 1935, partly because of an accident at a picnic. He and his sons were tossing firecrackers. Averill picked up one that had failed to go off and it exploded in his right hand, tearing flesh on his fingers and palm and burning his forehead and chest. The injury caused him to miss some regular-season games and the All-Star Game. He ended that season at a sub-par for him .288, but bounced back with perhaps his strongest season in 1936. He had a career-best .378 batting average with 232 hits, the most in the majors.

His hometown loved it. As longtime Snohomish resident Keith Gilbertson Sr. recalled, "During the Depression, this town didn’t have much pride. But we always had Earl Averill. No matter what was going on at the time, you knew you could pick up the paper every morning and see how many hits Earl Averill got" (Johnson, Everett Herald, 2005).

End of the Line

In 1937 Averill was diagnosed with a congenital spine malformation that caused temporary paralysis in his legs. The condition slowed him in the field and forced him to alter his hitting style, resulting in another sub-par season. Still, he managed to play in 156 games. He bounced back in 1938 to hit .330, but missed 20 games. His body was wearing down.

Recognizing one of the best players in team history, the Indians honored him with an Earl Averill Day ceremony that included the gift of a $2,400 Cadillac. He rode on its fender around the cinder track at Cleveland Municipal Stadium, a career victory lap in front of about 37,000 cheering fans. Soon after that he was gone. About a month into the 1939 season, the Indians traded him to the Detroit Tigers. He was hitting only .273 with one home run at the time, and dropped to .262 with Detroit to complete his worst major league season. He helped the Tigers win the league championship in 1940, but only as a part-time player.

Averill was 39 in 1941 when he started the season with the National League’s Boston Braves. They released him after only eight games, ending his major league career on April 25, 1941. He finished out the season with the Seattle Rainiers, helping them win the Pacific Coast League championship. And then he went home to Snohomish.

Restless in Retirement

Retired from baseball, Averill was co-owner of the family greenhouse, Averill Floral, until 1950, when he bought a motel, which he and Loette ran for the next 20 years. Meanwhile, baseball was never far from his mind, especially starting in 1956, when his son Earl Douglas Averill -- often called Earl Jr. -- started a major league career of his own with the Cleveland Indians.

Earl Jr. had been a standout player at the University of Oregon, good enough to make the university and state sports halls of fame, but he was only a journeyman as a big leaguer. He played parts of seven seasons with four teams, mostly as a catcher, and had a modest career batting average of .242. He ended his playing days in 1965 after two minor league seasons in Seattle, close enough for his father to attend nearly every game. "I tried to follow in the footsteps of my dad, and that was a mistake because there was no following him," the younger Averill said (Raley, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 2003).

By 1970, Averill was retired from the motel business, spending his time fishing, playing poker, and watching major league games on television. He also was wondering why he hadn’t been named to the Baseball Hall of Fame. So were many others, especially in his home state. A campaign to get him selected included an "Earl Averill Day" proclaimed by Washington Governor Dan Evans (b. 1925), and "Earl Averill Appreciation Night," a dinner program in Everett that drew 400 people.

Even 33 years after his last baseball season, The Earl of Snohomish had a certain bearing and a presence. Gene Johnston wrote this description for The Seattle Times in 1974: "Only about 5 feet 9 inches and 175 pounds, he’s one of those superbly built men with drill sergeant carriage who seem to get taller and broader as they approach. He was called ‘Rock’ in the big leagues and it’s hard to believe he’s 72 years old." Johnston’s story was titled "Why Isn’t Earl Averill in Baseball Hall of Fame?" One explanation for the question was that some voters believed his fielding was not Hall of Fame-worthy. The septuagenarian bristled at the thought. "I could do it all; don’t kid yourself," he said. "I’ll admit that around once a season my back would give me real trouble. I have a congenital defect that hampered my bending down, but I could field with anyone" (Johnston, The Seattle Times, 1974).

A Hall of Famer At Last

He had been eligible for 29 years when the call finally came. On February 3, 1975, a special committee formed to consider old-timers overlooked in the regular Hall of Fame balloting voted unanimously to include Averill. Warren Giles, former National League president and head of the committee, called to give him the news. "My ambition is reached. I really longed for this," Averill told the Associated Press. To a Seattle Times writer, he said being picked unanimously "kind of makes up for the long wait," and added "It’s wonderful to make it while you are still alive" (Zimmerman, The Seattle Times, 1975).

Averill was officially inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame on August 18, 1975, becoming the first player born in Washington state to achieve that honor (he has since been joined by two other native Washingtonians -- Ryne Sandberg [b. 1959] of Spokane in 2005 and Ron Santo [1940-2010] of Seattle in 2011). Joining Averill for the ceremony in Cooperstown, New York, were his wife, their four sons, daughters-in-law, and grandchildren. A trace of bitterness was evident in his acceptance speech. "I was convinced I was qualified to be a member, but apparently statistics alone are not enough to gain a player such recognition," he said. "Had I been elected after my death, I had made arrangements that my name never be placed in the Hall of Fame" (Patton, Toronto Globe and Mail, 1983).

The Cleveland Indians also honored Averill. They retired his jersey number, making him just the third Cleveland player to receive such recognition. ''They told me I was the greatest player ever to wear their uniform,'' Averill said. ''I thanked them but I didn't believe it'' (The New York Times, 1983).

Last Hurrahs

On July 6, 1983, Averill attended the 50th All-Star Game at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. As part of the anniversary celebration, the remaining 13 of the original 33 All-Stars were recognized. He came home sick and dispirited. "I think it bothered Dad that so many of his buddies had passed away," Earl Averill Jr. said. "He knew he was getting older. He had a real good time in Chicago, but when he got back he was really down" (Philadelphia Inquirer, 1983).

On July 11, Averill entered Everett’s Providence Hospital with pneumonia. His respiratory problems worsened and he never made it back home. He died on August 16, 1983, and was buried in the Grand Army of the Republic Cemetery in Snohomish. Newspapers around the country ran his obituary. The Everett Herald paid him tribute: "A great player became part of history yesterday. Earl Averill left us with a long trail of his achievements worthy of his Hall of Fame status, a bevy of notable feats, statistics that are unmatched by even some of history’s great players, and enough memories to keep the old timers talking a long time" (Beard, Everett Herald, 1983).

In 2005, the Herald proclaimed Averill the best athlete in Snohomish County history. That was no small distinction, as evidenced in 2010 by the names in the inaugural class of the county’s Sports Hall of Fame. Besides Averill, they included Chris Chandler, a former University of Washington quarterback who played in the National Football League for 17 years; former Washington State University football coach Dennis Erickson, who won two national championships at the University of Miami and also coached the National Football League’s Seattle Seahawks; college basketball Hall of Famer Marv Harshman (1917-2013), who coached at Pacific Lutheran University, WSU, and UW; Anne Quast, one of the most dominant woman amateur golfers in U.S. history; Olympic silver medalist figure skater Rosalynn Sumners; and All-American George Wilson, considered by some to be the greatest UW football player ever.

Lasting Memorials

Cleveland did its part to memorialize Averill. When Jacobs Field (later named Progressive Park) opened in 1994, he was among the former players honored with permanent displays. Inside, along the outfield wall, the franchise’s Hall of Famers form the top row of the Indians’ Ring of Fame. Outside, on the bowed brick wall of the park’s lower level, are plaques for Averill and the rest of the players named as the 100 best in franchise history. Earl Douglas Averill represented his father at the park’s opening ceremonies and was given a framed replica of Averill’s No. 3 Indians jersey.

Snohomish also made efforts to remember Averill, although not without creating some hard feelings. Over the years, Averill Field, the town’s baseball diamond, had been reduced to a Little League venue, bereft of its lights and grandstands. In September 2000 the city council voted to convert the property to a skateboard park and youth center, while also voting to name a bigger diamond at Pilchuck Park for Averill. Family and friends of the Averills were upset. The old field was replaced in 2001, the field at Pilchuck Park dedicated in Averill’s name in 2002. Later that year a sign was erected at the site of the original field: "Dedicated to Earl Averill -- the Earl of Snohomish" and a second sign was approved for near the diamond at Pilchuck Park.

Howard Averill, then 79, had opposed the elimination of the original field. Asked what he thought about the plan to add the signs, he replied, "Well, who’s the most famous person from the city? Yeah, it’s good" (Everett Herald, 2002).